Racism in Football: Tackling Abusive Behaviour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anti-Doping in Football Project Has Been Funded with Support from the European Commission (ERASMUS+ Sport 2019)

This Anti-Doping in Football project has been funded with support from the European Commission (ERASMUS+ Sport 2019). This publication and all its contents reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. Anti-Doping in Football Historically anti-doping efforts have focused on the detection and deterrence of doping in elite sport and football has not been an exception. However, there is a growing concern among policy makers and sport stakeholders that doping outside the elite sporting system is an expanding and problematic phenomenon, giving rise to the belief that the misuse of doping agents in recreational sport has become a societal problem and a public health concern. Whereas the latter is happening at high level, the same level of awareness is missing among amateur football players representing a major issue if we consider the social harm and impact upon both users and sport communities doping abuse might create. The use of drugs in football is not widely associated with the sport because of lack of evidence, unlike individual sports such as cycling, weight-lifting, and track and field. Much closer collaboration and further investigation is needed with regard to banned substances, detection methods, and data collection. This project addresses the issue of awareness and support at the amateur grassroots football level. Despite calls from European institutions through official documents and expert groups for coherent approaches, there is much to be done in football. The lack of a coordinated approach ANTI-DIF PROJECT I APRIL 2019 I [email protected] 1 at EU level undermines also the possibility to have a comprehensive picture of the overall situation to understand which actions must be urgently delivered. -

View Programme Catalogue

UEFA Academy Catalogue Aleksander Čeferin UEFA President INTRODUCTION o perform well on the pitch, teams require talented Beyond certified education programmes, UEFA also and well-trained players. Football organisations encourages knowledge sharing among its member Tare no different: to navigate the complexities associations and stakeholders to promote solidarity of modern football, national associations and their and equality within the football community. The 55 UEFA stakeholders need talented and well-trained employees member associations cover a broad geographical area, and leaders. This is why UEFA has launched a series of incorporating many diverse cultures, working methods education programmes and knowledge-sharing initiatives and professional good practices. The knowledge-sharing for the continuous development of football professionals. initiatives recognise this collective expertise as a valuable Since 2019, these learning initiatives have been commodity and are intended as platforms for sharing combined under the umbrella of the UEFA Academy. these resources and ultimately enhancing the level of professionalism in the game. The education programmes run by the UEFA Academy bring together top professionals in the game and forward- This brochure presents the various learning initiatives thinking academics. One of the strengths of our courses the UEFA Academy offers to support football is this balance between theoretical knowledge and management throughout Europe. From continuous professional expertise. Held at UEFA headquarters and learning for national association staff and stakeholders some of the most iconic football facilities in Europe, our to knowledge-sharing platforms, there are numerous programmes will take you to the heart of European football. opportunities for organisations and their employees Thanks to partnerships with leading European academic to develop. -

I. Europe N.B

QUOTA FOR FOREIGN FOOTBALL PLAYERS ALLOWED TO PLAY IN A CLUB A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS AT NATIONAL LEVEL (Updated to 30 of May 2008) A simple research coordinated by Michele Colucci ([email protected]) I. EUROPE N.B. FOR EU MEMBER STATES REFERENCE IS MADE ONLY TO NON EU-PLAYERS AUSTRIA: - No quota for non EU-players. Nevertheless with regard to the national league, clubs needs to have at least 10 players eligible to play for the National team on the roster in order to get money from TV. BELGIUM: - No quota for non EU-players. But Gentlemen's Agreement between clubs in first category: 4 of the 18 home grown players (2007/2008), 5 in 2008/2009 and 6 in 2009/2010. N.B. Minimum salary: Gross Amount of 65.400 euros + Holiday Fee (1 extra monthly wage + 1 match bonus) + pension fund BELARUS: Visshaja Liga (First Category): - 5 foreigners, but only 4 to be fielded Pervaja Liga (Second Category) - No limits BULGARIA: A PFG (First Category): - up to 5 Non-EU players may be contracted and all of them may be fielded B PFG (Second Category): - non EU-players may not be contracted No limits only for EU players. 1 This is according to article 22.2. of the Regulations of the Bulgarian Football Union on the Competition Rights of the Football Players for the season 2007/2008 CZECH REPUBLIC: - For 1st and 2nd league- and for professionals: no quota for non EU- players, but only 3 to be fielded. CROATIA: - No quota for foreigners, but only 4 to be fielded DENMARK: -No quota for non EU-players, but only 3 to be fielded from outside Europe. -

Match‐Fixing and Legal Systems. an Analysis of Selected Legal Systems

Project Number: 590606‐ EPP‐1‐2017‐1‐PL‐SPO‐SCP Match‐fixing and legal systems. An analysis of selected legal systems in Europe and worldwide with special emphasis on disciplinary and criminal consequences for corruption in sport and match‐fixing. Kirstin Hallmann, Severin Moritzer, Marc Orlainsky, Korneliya Naydenova, Fredy Fürst Project Number: 590606‐ EPP‐1‐2017‐1‐PL‐SPO‐SCP Publisher German Sport University Cologne Institute of Sport Economics and Sport Management Am Sportpark Müngersdorf 6 50933 Köln/Cologne Kirstin Hallmann, Severin Moritzer, Marc Orlainsky, Korneliya Naydenova, Fredy Fürst October 2019 Match‐fixing and legal systems. An analysis of selected legal systems in Europe and worldwide with special emphasis on disciplinary and criminal consequences for corruption in sport and match‐fixing. Cologne: German Sport University, Institute of Sport Economics and Sport Management ISBN 978‐3‐00‐064119‐0 Intellectual Output IO1 of the Project ‘Against match‐fixing – European Research & Education Program’, Project Number: 590606‐ EPP‐1‐2017‐1‐PL‐SPO‐SCP Visual Title: Kirstin Hallmann i Project Number: 590606‐ EPP‐1‐2017‐1‐PL‐SPO‐SCP Management Summary In this report, a description and analysis of the criminal law and disciplinary law regulations of the football associations in European countries and selected countries in Asia and South America were conducted. The legal analysis covers a total of 12 countries and four continents, including eight European countries (Austria, Bulgaria, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Poland, United Kingdom), two Asian countries (Japan, South Korea), one South American country (Paraguay) and one country from Oceania (Australia). Some of the most relevant key findings and recommendations are: 1. -

UEFA"Direct #154 (01.12.2015)

WE CARE ABOUT FOOTBALL No. 154 | December 2015 IN THIS ISSUE Official publication of the EXecutiVE COMMittee MeetS IN PARIS 4 Union of European Football Associations The UEFA Executive Committee met the day before the EURO 2016 final draw for its last meeting of the year. Chief editor: Emmanuel Deconche UEFA Produced by: GraphicTouch CH-1110 Morges EURO 2016 FINAL Draw Printing: 5 Artgraphic Cavin SA Following the EURO 2016 final draw in Paris on 12 December, CH-1422 Grandson all the teams now know which groups they are in. Images Editorial deadline: 14 December 2015 Getty The views expressed in signed articles are not necessarily the official views of UEFA. SERBIA awaitiNG FUTSAL EURO 2016 7 The reproduction of articles published in UEFA·direct Serbia is all geared up to welcome the 11 teams who will is authorised, provided the be joining its own futsal team from 2 February to compete source is indicated. for the title of European futsal champions. Serbia of FA YOUTH coMpetitioN DrawS 8 The draws for the elite rounds of the current boys’ and girls’ Under-17 and Under-19 European championships and the 2016/17 qualifying rounds were held at UEFA headquarters in November and December. UEFA A NEW courSE for forMER playerS 14 Cover: Zlatan Ibrahimović scored The first module in the new UEFA Executive Master for three goals in his country’s International Players took place in Nyon from 16 to 20 November. EURO 2016 qualifying play-offs against Denmark to take Sweden through UEFA to the first 24-team EURO Photo: Getty Images NEWS froM MEMBER ASSociatioNS 17 2 | UEFA •direct | 12.15 Editorial UEFA FRANCE Set for A FESTIVAL OF football The UEFA EURO 2016 final draw at the Palais are being put to the stadiums that will host des Congrès in Paris provided us with an oppor- the 51 matches, to ensure that they meet UEFA’s tunity to look back as well as forward. -

The Composition and Geography of Bulgarian Olympic Medals, 1952–2016

The International Journal of the History of Sport ISSN: 0952-3367 (Print) 1743-9035 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fhsp20 The Composition and Geography of Bulgarian Olympic Medals, 1952–2016 Kaloyan Stanev To cite this article: Kaloyan Stanev (2017) The Composition and Geography of Bulgarian Olympic Medals, 1952–2016, The International Journal of the History of Sport, 34:15, 1674-1694, DOI: 10.1080/09523367.2018.1484730 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2018.1484730 Published online: 22 Oct 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 51 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fhsp20 THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF THE HISTORY OF SPORT, 2017 VOL. 34, NO. 15, 1674–1694 https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2018.1484730 The Composition and Geography of Bulgarian Olympic Medals, 1952–2016 Kaloyan Stanev Department of Economics & Business, Pompeu Fabra University, Barcelona, Spain ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Bulgaria was one of the leading sport nations of the second half Geographical information of the twentieth century; however, the Bulgarian national anthem systems; Olympic success; has not been played at Olympic Games since 2008. In the current totalitarian planning; article, historical records on planning are compared to the results Bulgarian Sport; wrestling and weightlifting of athletes to determine the factors behind the remarkable rise and decline of Bulgarian sport during the last six decades. Historical geographical information systems (GISs) are used to analyze the spatial distribution of Olympic medals in each of the successfully developed sports. -

Bulletin TAS CAS Bulletin

Bulletin TAS CAS Bulletin 2/ 2013 Bulletin TAS CAS Bulletin 2/ 2013 Table des matières / Table of contents Message du Secrétaire Général du TAS / Message of the CAS Secretary General Message of the CAS Secretary General .................................................................................................................................. 1 Articles et commentaires / Articles and commentaries The jurisprudence of the Swiss Federal Tribunal on challenges against CAS awards.................................................... 2 Prof. Massimo Coccia CAS jurisprudence related to the elimination or reduction of the period of ineligibility for specifi ed substances ........................................................................................................................................................... 18 Ms Estelle de La Rochefoucauld, Counsel to the CAS Jurisprudence majeure / Leading cases Arbitration CAS 2011/A/2362 ..............................................................................................................................................28 Mohammad Asif v. International Cricket Council (ICC) 17 April 2013 Arbitration CAS 2011/A/2566 .............................................................................................................................................34 Andrus Veerpalu v. International Ski Federation (ISF) 25 March 2013 Arbitration CAS 2012/A/2754 ............................................................................................................................................. -

EURO 2008 Final Draw in Lucerne Spain Retain Their

UEFAdirect-69-Janvier•E:Anglais 17.12.2007 12:28 Page 1 1.0 8 Including EURO 2008 final draw in Lucerne 03 Spain retain their European futsal title 06 Changes to the UEFA club competitions 11 2010 World Cup qualifying groups 15 No 58 – Février 2007 69 January 2008 UEFAdirect-69-Janvier•E:Anglais 17.12.2007 12:11 Page 2 Message Photos: UEFA-pjwoods.ch of the president Keep dreaming The year is drawing to a close, the nights are getting longer and the festive season gives them that magical feel which is so conducive to dreams. This time last year, I had a dream. I dreamt about becoming UEFA President and, in January, the delegates of the national associations made my dream come true by electing me at the Congress in Düsseldorf. I still have dreams, lots of dreams, and they can also come true if we all join forces and make a determined effort. I dream that football will continue to fill everyday life with passion and emotion; that we will learn to consider it again as a game first and foremost and not as a source of profit; that the politicians will do everything in their power to allow the game to regulate itself, democratically and with appropriate legislation; that, out of the stadiums, a formidable surge of solidarity will emerge and that a wave of sportsmanship will sweep away racism and all forms of discrimination; that respect for others will prevail at all times; and, above all, that football will continue to make children’s eyes sparkle with wonder – something it does so well. -

National Sports Federations (Top Ten Most Popular Olympic Sports)

National Sports Federations (top ten most popular Olympic sports) Coverage for data collection 2015, 2018-2020 Country Name (EN) EU Member States Belgium Royal Belgian Swimming Federation Royal Belgian Athletics Federation Royal Belgian Basketball Federation Belgian Cycling Belgian Equestrian Federation Royal Belgian Football Association Royal Belgian Golf Federation Royal Belgian Hockey Association Royal Belgian Federation of Yachting Royal Belgian Tennis Federation Bulgaria Bulgarian Athletics Federation Bulgarian Basketball Federation Bulgarian Boxing Federation Bulgarian Football Union Bulgarian Golf Association Bulgarian Rhythmic Gymnastics Federation Bulgarian Wrestling Federation Bulgarian Tennis Federation Bulgarian Volleyball Federation Bulgarian Weightlifting Federation Czech Republic Czech Swimming Federation Czech Athletic Federation Czech Basketball Federation Football Association of the Czech Republic Czech Golf Federation Czech Handball Federation Czech Republic Tennis Federation Czech Volleyball Federation Czech Ice Hockey Association Ski Association of the Czech Republic Denmark Danish Swimming Federation Danish Athletic Federation Badminton Denmark Denmark Basketball Federation Danish Football Association Danish Golf Union Danish Gymnastics Federation Danish Handball Federation Danish Tennis Federation Danish Ice Hockey Union Germany German Swimming Association German Athletics Federation German Equestrian Federation German Football Association German Golf Association German Gymnastics Federation German Handball Federation -

Decision Member of the FIFA Disciplinary Committee

Decision of the Member of the FIFA Disciplinary Committee Mr. Lord VEEHALA [TGA], Member on 12 February 2020 to discuss the case of: Club PFC CSKA-Sofia, Bulgaria (Decision 140533 PST) ––––––––––––––––––– regarding: failure to comply with art. 15 of the FDC (2019 ed.) / art. 64 FDC of the FDC (2017 ed.) –––––––––––––––––– 1 I. inferred from the file1 1. On 28 August 2013, the Single Judge of the Players’ Status Committee decided that the club PFC CSKA Sofia (hereinafter also referred to as “the original Debtor”) had to pay the following amounts: - To the players’ agent, Ms Soukeyna Ba Bengelloun (hereinafter also referred to as “the Creditor”): EUR 50,000 as follows: o EUR 30,000 as well as 5% interest per year on the said amount as from 15 December 2012 until the date of effective payment, within 30 days as from the date of notification of the decision; o EUR 20,000 as well as 5% interest per year on the said amount as from 28 February 2013 until the date of effective payment, within 30 days as from the date of notification of the decision. CHF 2,000 as costs of the proceedings. - To FIFA: CHF 6,000 as costs of the proceedings. 2. The terms of the decision of the Single Judge of the Players’ Status Committee were duly communicated to the parties on 17 September 2013. Moreover, the grounds of the aforementioned decision were, upon request of the original Debtor, notified to the parties on 5 November 2013. Finally, no appeal was filed before the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS). -

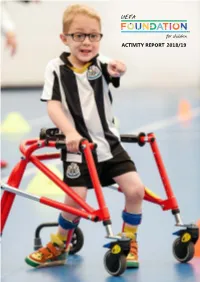

Interactive Activity Report 2018/19

ACTIVITY REPORT 2018/19 3 Editorial 4 Inside the foundation Editorial IMPRESSUM 6 New projects in Africa Over the past year, the UEFA Foundation for Children, which uses foot- Nations, has expressed a wish to assist the UEFA Foundation for EDITORIAL ball as a vehicle to help children and protect their rights, has sub- Children with projects in Guinea and Gambia. Tania Baima, Eileen Herrick, Cyril Pellevat, Pascal Torres 12 New projects in Asia stantially increased the level of funding it has available to support its PHOTOS projects. I am grateful to the foundation’s trustees, the national associ- Under these three pillars, the foundation has directly supported 45 new Action for Development ations and the UEFA authorities for supporting the foundation’s work. projects. This year, the foundation has continued to help national foot- New projects in Europe ActionAid Hellas ball associations fulfil their role within their communities. Through 16 AFRANE AMANDLA To meet the demands of the modern world and respect the founda- the national associations, it has contributed to 22 other projects that Amp Futbol Polska tion’s mandate, we have laid out a three-pillar strategy for the years ahead. are designed to help children and safeguard their rights. 26 New projects in the Americas Ayuda en Acción Baan Dek Foundation I am delighted that UEFA’s partners have agreed to back this strategy. Cross Cultures Project Association (CCPA) With the help of all the foundation trustees, we will continue to Equalizer programme 29 Project in Oceania European Football for Development Network (EFDN) The first pillar is continued support for general development pro- strengthen the foundation’s activities by increasing our efficiency Everton in the Community grammes based on sport, in particular football. -

No. 145 | January - February 2015 in This Issue

WE CARE ABOUT FOOTBALL No. 145 | January - February 2015 IN THIS ISSUE Official publication of the EXecutiVE COMMittee MeetiNG 4 Union of European Football Associations The UEFA Executive Committee held its first meeting of 2015 Images at UEFA’s headquarters in Nyon on 26 January. Getty via Chief editor: Emmanuel Deconche UEFA Produced by: GraphicTouch CH-1110 Morges electioNS IN VIENNA Printing: 5 Images Artgraphic Cavin SA Michel Platini is the sole candidate for the UEFA Presidential CH-1422 Grandson election at the UEFA Congress in Vienna in March, while Getty Editorial deadline: 12 candidates are standing for seven seats on the UEFA Executive via 6 February 2015 Committee. UEFA The views expressed in signed articles are not necessarily the official views of UEFA. REFEREE courSES IN ATHENS 10 The reproduction of articles published in UEFA·direct The annual winter courses for UEFA referees took place is authorised, provided the in Greece at the beginning of February. source is indicated. Sportsfile PreparatioNS for EURO 2016 15 With less than 500 days to go, preparations are gaining momentum. Sportsfile Sportsfile Cover: SEMINAR ON INSTITUTIONAL Real Madrid won their fourth trophy of the year at the DISCRIMINatioN IN football 17 Club World Cup in Morocco Amsterdam was the venue on 12 December for a (Gareth Bale in white and Chamid San Lorenzo de Almagro’s UEFA seminar on institutional discrimination in football. Juan Mercier) Soenar Photo: AFP / Getty Images NEWS froM MEMBER ASSociatioNS 19 2 | UEFA •direct | 01-02.15 Editorial UEFA Football AS A force for GooD Football is truly magical; therefore it does not have the support of ambassadors like Christian surprise me that its popularity continues to soar.