Thejasminebrand.Com Thejasminebrand.Com Case 1:13-Cv-08915-ER Document 14 Filed 05/06/14 Page 1 of 34

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PARKER (Tratto Dal Romanzo Flashfire Di Donald E

Indie Pictures s.p.a. Presenta PARKER (tratto dal romanzo Flashfire di Donald E. Westlake) Diretto da : Taylor Hackford Con: Jason Statham, Jennifer Lopez, Nick Nolte, Michael Chiklis Durata: 118’ Data di uscita: 8 maggio 2014 UFFICIO STAMPA Studio Sottocorno - Lorena Borghi Tel. +39 02 20402142 Email [email protected] ; [email protected] [email protected] PARKER – IL CONCEPT Un criminale di professione con un impeccabile codice d'onore è alla ricerca di vendetta contro la banda che gli ha giocato un brutto colpo in PARKER, un grintoso e moderno film noir ambientato nella ricchezza senza pari e il fascino di Palm Beach. Diretto dal premio Oscar Taylor Hackford, PARKER è la riduzione cinematografica di uno dei romanzi più celebri del famoso scrittore Donald E. Westlake, e porta per la prima volta sullo schermo l’antieroe che ne è protagonista. Audace, meticoloso e spietato, Parker (interpretato da Jason Statham) è un esperto di pianificazione e di esecuzione di furti apparentemente impossibili. Ai suoi collaboratori chiede assoluta lealtà e preciso rispetto dei piani. Ma quando la sua ultima rapina ha risvolti mortali a causa della disattenzione di un membro della squadra, Parker rifiuta di unirsi al boss Melander (Michael Chiklis) e alla sua banda per il loro prossimo grande colpo. Non disposti ad accettare un no i criminali aggrediscono Parker, lasciandolo apparentemente morto sul ciglio di una strada deserta. Sopravvissuto all'aggressione e deciso a vendicarsi contro gli uomini che lo hanno tradito, Parker si mette sulle tracce della banda fino a giungere alla sfarzosa Palm Beach. Fingendosi un ricco texano alla ricerca di una casa, incontra Leslie (Jennifer Lopez), un’agente immobiliare dotata di una conoscenza enciclopedica della zona. -

Emmy Nominations

2021 Emmy® Awards 73rd Emmy Awards Complete Nominations List Outstanding Animated Program Big Mouth • The New Me • Netflix • Netflix Bob's Burgers • Worms Of In-Rear-Ment • FOX • 20th Century Fox Television / Bento Box Animation Genndy Tartakovsky's Primal • Plague Of Madness • Adult Swim • Cartoon Network Studios The Simpsons • The Dad-Feelings Limited • FOX • A Gracie Films Production in association with 20th Television Animation South Park: The Pandemic Special • Comedy Central • Central Productions, LLC Outstanding Short Form Animated Program Love, Death + Robots • Ice • Netflix • Blur Studio for Netflix Maggie Simpson In: The Force Awakens From Its Nap • Disney+ • A Gracie Films Production in association with 20th Television Animation Once Upon A Snowman • Disney+ • Walt Disney Animation Studios Robot Chicken • Endgame • Adult Swim • A Stoopid Buddy Stoodios production with Williams Street and Sony Pictures Television Outstanding Production Design For A Narrative Contemporary Program (One Hour Or More) The Flight Attendant • After Dark • HBO Max • HBO Max in association with Berlanti Productions, Yes, Norman Productions, and Warner Bros. Television Sara K. White, Production Designer Christine Foley, Art Director Jessica Petruccelli, Set Decorator The Handmaid's Tale • Chicago • Hulu • Hulu, MGM, Daniel Wilson Productions, The Littlefield Company, White Oak Pictures Elisabeth Williams, Production Designer Martha Sparrow, Art Director Larry Spittle, Art Director Rob Hepburn, Set Decorator Mare Of Easttown • HBO • HBO in association with wiip Studios, TPhaeg eL o1w Dweller Productions, Juggle Productions, Mayhem Mare Of Easttown • HBO • HBO in association with wiip Studios, The Low Dweller Productions, Juggle Productions, Mayhem and Zobot Projects Keith P. Cunningham, Production Designer James F. Truesdale, Art Director Edward McLoughlin, Set Decorator The Undoing • HBO • HBO in association with Made Up Stories, Blossom Films, David E. -

Lorenzo O'brien Producer Work Experience

LORENZO O'BRIEN PRODUCER WORK EXPERIENCE 2020-2021 LINE PRODUCER – “ACAPULCO/ALMOST PARADISE SEASON 1” – 10 Episodes (Mexico) – TV Series Produced by Lionsgate Television- Apple+, Santa Monica, California. Director: Richard Shepard, Jay Karras, Tristam Shapeero. 2018-2019 PRODUCER – “NARCOS SEASON 5” – 10 Episodes (Mexico) – TV Series Produced by Gaumont International Television and Netflix, Beverly Hills, California. EP: Eric Newman. Directors: Amat Escalante, Marcela Said and Andy Baiz. 2017-2018 PRODUCER - “NARCOS SEASON 4” (Mexico) – 10 Episodes (Mexico/U.S.) – TV Series Produced by Gaumont International Television and Netflix, Beverly Hills, California. EP: Eric Newman. Directors: Amat Escalante, Josef Wladika, Alonso Ruizpalacios and Andy Baiz. 2016-2017 PRODUCER – “NARCOS SEASON 3” (Colombia) – 10 Episodes (Colombia/U.S.) – TV Series Produced by Gaumont International Television and Netflix, Beverly Hills, California. EP: Eric Newman. Directors: Fernando Coimbra, Gabriel Ripstein, Josef Wladika and Andy Baiz, 2015-2016 PRODUCER – “NARCOS SEASON 2” (Colombia) – 10 Episodes (Colombia/U.S.) – TV Series Produced by Gaumont International Television and Netflix, Beverly Hills, California. EP: Eric Newman. Directors: Gerardo Naranjo, Josef Wladika and Andy Baiz, PRODUCER/MEXICO – “RUNNER” (Mexico) – TV Pilot Produced by 20th Century Fox Television, Beverly Hills, California. Director: Michael Offer. PRODUCER – “QUEEN OF THE SOUTH” (Mexico) – TV Pilot Produced by Fox 21 Studios, Beverly Hills, California. Director: Charlotte Sieling. 2014 PRODUCER – “OUTLAW PROPHET” (U.S.) – TV MOW Produced by Sony Pictures Television, Culver City, California. Director: Gabriel Range. 2013 CO-PRODUCER – “THE LAST WORD” (U.S.) – Feature Produced by Boss Media, LLC., Beverly Hills, California. Director: Simon Rumley. EXECITIVE PRODUCER – “LYNCH” – 8 Episodes – (Argentina) – TV Series Produced by Movie City, Atlanta, Georgia, and Fox Tele-Colombia, Bogota, Colombia. -

Brevard Live October 2018

Brevard Live October 2018 - 1 2 - Brevard Live October 2018 Brevard Live October 2018 - 3 4 - Brevard Live October 2018 Brevard Live October 2018 - 5 6 - Brevard Live October 2018 Contents October 2018 FEATURES FRANNIPALOOZA Franni’s music quest started in 1980 WAR COMES TO BREVARD when she arrived in Florida. She worked Columns War, featuring original member Lonnie for years at the legendary Musicians Ex- Charles Van Riper Jordan, is coming to Brevard to play all change in Fort Lauderdale. Now she is 20 Political Satire their greatest hits…and there are quite a booking famous Blues artists at Earl’s It’s That Time few. The concert takes place at SC Har- Hideaway. She truly is a legend among ley Davidson and benefits The Great legends. Brevard Live talked to her. Calendars Leaps Academy. Page 14 27 Live Entertainment, Page 10 Concerts, Festivals WOMEN WHO ROCK! SPACE COAST STATE FAIR Karalyn Woulas is a rocket scientist, an The Mandela Effect The Space Coast State Fair is Brevard’s avid surfer, front-lady of 2 bands - The by Matt Bretz largest and most popular annual family 35 Lady & The Tramps and Karalyn & The Human Satire event. Located in the middle of Brevard Dawn Patrol - a politician and enjoys County, and easily accessible from Inter- riding her Harley Davidson Sportster. state-95, The Space Coast State Fair is a Local Lowdown short ride from all areas of Brevard Page 18 36 by Steve Keller Page 13 Jam Night! MIFF PROGRAM by Heike Clarke NATIVE RHYTHMS FESTIVAL The Melbourne Independent Filmmak- 39 The 10th annual Native Rhythms Fes- ers Festival is a jewel for fans of the in- The Dope Doctor tival will be held at the Wickham Park dependent short film. -

Production Notes

PRODUCTION NOTES “This city, this whole country, is a strip club. You’ve got people tossing the money, and people doing the dance.” – Ramona Inspired by true events, HUSTLERS is a comedy-drama that follows a crew of savvy strip club employees who band together to turn the tables on their Wall Street clients. At the start of 2007, Destiny (Constance Wu) is a young woman struggling to make ends meet, to provide for herself and her grandma. But it’s not easy: the managers, DJs, and bartenders expect a cut– one way or another – leaving Destiny with a meager payday after a long night of stripping. Her life is forever changed when she meets Ramona (Jennifer Lopez), the club’s top money earner, who’s always in control, has the clientele figured out, and really knows her way around a pole. The two women bond immediately, and Ramona gives Destiny a crash course in the various poses and pole moves like the carousel, fireman, front hook, ankle-hook, and stag. Another dancer, the irrepressible Diamond (Cardi B) provides a bawdy and revelatory class in the art of the lap dance. But Destiny’s most important lesson is that when you’re part of a broken system, you must hustle or be hustled. To that end, Ramona outlines for her the different tiers of the Wall Street clientele who freQuent the club. The two women find themselves succeeding beyond their wildest dreams, making more money than they can spend – until the September 2008 economic collapse. Wall Street stole from everyone and never suffered any consequences. -

Executive Producer/Writer

‘BANNER 4th OF JULY’ PRODUCTION BIOS MICHAEL VICKERMAN (Executive Producer/Writer) – Michael Vickerman is a native of Minneapolis, Minnesota and attended film school at the University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee before transferring to Columbia Film School. He began working as a professional writer at the age of 20 while working as a production assistant for Sylvester Stallone’s White Eagle Entertainment. Stallone read a screenplay Vickerman had written for a school project and subsequently commissioned him to write scripts for his company, including uncredited rewrites on the International blockbuster “Cliffhanger.” Shortly after graduation Vickerman was hired by Law Brothers Entertainment to write and develop both a screenplay and children’s books for their toy creation “Kung Fu Kangaroos.” The movie became “Warriors of Virtue,” a $35 million MGM production that was released in 1997. Over the next fifteen years Vickerman has written, directed and/or produced eighteen films, starring such renowned actors as Timothy Hutton (Academy Award® winner for “Ordinary People”), James Cromwell (“L.A. Confidential” and “Babe”), Leighton Meester (“Gossip Girl”), Marcia Cross (“Desperate Housewives”), Gina Gershon (“Bound” and “Face-off”), Chris Malone (“Law & Order SVU”), Dabney Coleman (“9 to 5” and “Tootsie”), Natasha Henstridge (“Species” and “Eli Stone”), David James Elliot (“Jag”), Jennie Garth (“90210”), Michael Gross (“Family Ties”) and others. In 2002 Vickerman directed “Clover Bend,” starring Robert Urich and David Keith and in 2004 wrote and directed “Warriors of Virtue: Return to Tao,” shot entirely in Beijing, China. He is currently in production on a Hallmark Channel holiday movie. Michael Vickerman currently resides in Los Angeles. ### JONAS PRUPAS (Executive Producer) - Jonas Prupas is General Manager of Muse Entertainment’s Toronto office overseeing Muse’s TV movies, documentaries and unscripted character-based series developed or filmed in Ontario. -

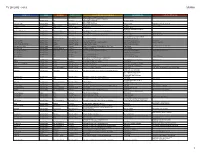

Tv Shows - 2019 Drama

TV SHOWS - 2019 DRAMA SHOW TITLE GENRE NETWORK SEASON STATUS STUDIO / PRODUCTION COMPANIES SHOWRUNNER(S) EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS 68 Whiskey Episodic Drama Paramount Network Ordered to Series CBS TV Studios / Imagine Television Roberto Benabib Fox TV Studios / 20th Century Fox Television, 911 Episodic Drama Fox Renewed Ryan Murphy Productions Timothy P. Minear, 20th Century Fox TV / 9-1-1: Lone Star Episodic Drama Fox Ordered to Series Ryan Murphy Productions Ryan P. Murphy Brad Falchuk; Timothy P. Minear A Million Little Things Episodic Drama ABC Television Renewed ABC Studios / Kapital Entertainment DJ Nash James Griffiths A Teacher Drama FX Network Ordered To Series FX Productions Hannah M. Fidell Jed Whedon; Maurissa Tancharoen; Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. Episodic Drama ABC Television Renewed ABC Studios / Marvel Entertainment; Mutant Enemy Jeffrey Bell Alive Episodic Drama CBS Entertainment Not Picked Up CBS TV Studios Jason Tracey Robert Doherty All American Episodic Drama CW Network Renewed Warner Bros Television / Berlanti Productions Nkechi Carroll, Gregory G. Berlanti Greg Spottiswood; Leonard Goldstein; All Rise Episodic Drama CBS Entertainment Ordered to Series Warner Bros Television Michael Robin; Gil Garcetti Almost Paradise Episodic Drama WGN America Ordered to Series Electric Entertainment Gary Rosen; Dean Devlin Marc Roskin Amazing Stories Episodic Drama Apple Ordered To Series Universal Television LLC / Amblin Television Adam Horowitz; Edward Kitsis David H. Goodman Amazon/Russo Bros Project Episodic Drama Amazon Ordered To Series Amazon Studios / AGBO Anthony Russo; Joe Russo American Crime Story Episodic Drama FX Network Renewed Fox 21; FX Productions / B2 Entertainment; Color Force Ryan Murphy Brad Falchuk; D V. -

Lifetime Films Chickflicks Productions & Juvee Productions Present

Lifetime Films Chickflicks Productions & JuVee Productions Present LILA AND EVE Starring: Viola Davis Jennifer Lopez Directed by: Charles Stone III Run Time: 94 Minutes www.lilaandevemovie.com To download press notes and photography, please visit: www.press.samuelgoldwynfilms.com USERNAME: press / PASSWORD: golden! Synopsis Short Synopsis: A tense and exciting film, LILA AND EVE is directed by Charles Stone III (DRUMLINE), and tells the story of Lila (Academy Award® Nominee Viola Davis), a grief-stricken mother who in the aftermath of her son’s murder in a drive-by shooting attends a support group where she meets Eve (Jennifer Lopez), who has lost her daughter. When Lila hits numerous roadblocks from the police in bringing justice for her son’s slaying, Eve urges Lila to take matters into her own hands to track down her son’s killers. The two women soon embark on a violent pursuit of justice, as they work to the top of the chain of drug dealers to avenge the murder of Lila’s son. ). A bold and provocative take on the morals of American society, LILA AND EVE will open in theaters and on demand on July 17, 2015. Long Synopsis: Struggling to cope with the loss of her 18-year old son Stephon after he falls victim to the drug violence in their neighborhood, a grieving mother Lila (Academy Award® Nominee Viola Davis), attends a support group for mothers of children who have been murdered. There she meets Eve (Jennifer Lopez), a candid kindred spirit. Lila commiserates with Eve on her desire for justice and the fact that the local police lack the resources necessary to pursue her son’s case. -

26 -Aida Hurtado J-Lo

Aida Hurtado MUCH MORE THAN A BUTT: Jennifer Lopez’s Influence On Fashion Jennifer López is the contemporary icon not only of Latinas in fashion but also of a Latina aesthetic in the embodiment of Latina style (Negrón-Muntaner, 2004). In many ways, the extensive fashion coverage that J.Lo (as she is known to her fans) has received is unprecedented for a U.S. Latina or Latino. Nevertheless, Latina/o culture has had a steady and important influence on how we adorn ourselves since at least 1848 at the end of the Mexican War, when much of what is now the southwestern United States became part of this nation. The end of the Mexican-American War in 1848 codified in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo the colonized status of Mexico’s former citizens in what became part of the U.S. southwestern states of Arizona, California, Colorado, New Mexico, and Texas. Mexicans residing in this region lost their citizen rights and saw their language and culture displaced overnight. Other non- Mexican Latino groups joined the United States after 1848. Fashion as Communication Code Latinas/os in the United States exist within the larger context of fashion trends and conventions, what some fashion theorists refer to as a “code” of communication, similar but not identical to the use of language. Nonetheless, as Fred Davis writes, “we know that through clothing people communicate some things about their persons, and at the collective level this results typically in locating them symbolically in some structural universe of status claims and life-style attachments” (Fashion, Culture, and Identity, p.4). -

Liz Imperio & Chad Carlberg

4605 Lankershim Blvd. #340 North Hollywood, CA 91601 PH: 323-462-5300 FAX: 323-462-0100 LIZ IMPERIO & CHAD CARLBERG CREATIVE DIRECTORS / CHOREOGRAPHERS FILM Spanglish Choreographer Sony Pictures Dir.: James Brooks Gotta Kick It Up Choreographer Disney Dus Choreographer Bollywood Obsessions Choreographer Imperio Productions Salsa Assistant Choreographer Golan-Globus Productions TELEVISION La Banda Creative Director and Choreographer Univision Latin American Music Awards Creative Director and Choreographer Telemundo NBC Billboard Latin Music Awards Creative Direction NBC / Jennifer Lopez Billboard Music Awards Creative Direction and Choreography ABC / Jennifer Lopez Jennifer Lopez: Dance Again Creative Direction and Choreography HBO / Nuyorican Productions ¡Q'Viva!: The Chosen Supervising Choreographer FOX / XIX Entertainment Dancing with the Stars w/ Sheila E Creative Direction and Choreography ABC USA Network Series – “The Moment” On Camera Mentor The Hochberg Ebersol Company American Music Awards—tribute to Celia Cruz Choreographer ABC / Jennifer Lopez Billboard Mexican Music Awards Choreography and Direction NBC / Telemundo American Idol – Finale Choreographer FOX Dancing with the Stars w/ Corbin Bleu Associate Choreographer ABC / Macy’s / Kenny Ortega Billboard Mexican Music Awards Choreographer Billboard / Telemundo J-Lo Live in Puerto Rico Choreography and Direction NBC / Jennifer Lopez Latin Grammy Awards Choreography and Direction Ivy Queen Conjunto Primavera Rock N’ Jock Choreographer MTV ABC 50th Anniversary Associate Choreographer -

Global Powerhouse Jennifer Lopez to Receive "Michael Jackson Video

Global Powerhouse Jennifer Lopez To Receive "Michael Jackson Video Vanguard Award" And Perform At The 2018 "VMAs" Airing Live On MTV Monday, August 20 At 9:00 PM ET/PT July 31, 2018 NEW YORK, July 31, 2018 /PRNewswire/ -- MTV today announced that global superstar Jennifer Lopez will receive the "Michael Jackson Video Vanguard Award" at the 2018 MTV "VMAs." She is also set to perform live at this year's show for the first time since 2001 and is nominated for two "VMAs" for her most recent single, "Dinero." With a legacy that spawns over two decades, Lopez is one of the most iconic and influential multi- hyphenates across music, film, television, fashion, business and philanthropy. DOWNLOAD PHOTO ASSETS HERE VIEW PROMO HERE Lopez joins a prestigious list of past Vanguard recipients that includes Michael Jackson, Madonna, Guns N' Roses, Britney Spears, Justin Timberlake, BEYONCÉ, Kanye West, Rihanna and P!nk. The "VMAs" will air live from Radio City Music Hall on Monday, August 20 at 9:00 PM ET/PT across MTV's global network of channels in more than 180 countries and territories, reaching more than half a billion households around the world. Since her first album, "On the 6," debuted in 1999, Lopez has transformed the global music scene, including selling over 80 million records worldwide, 40 million albums, 16 top 10 hit songs, and three #1 albums. In addition to her music, Lopez has made her mark in film and television. Her films have grossed over $2.9 billion worldwide, five of which opened at #1. -

Hispanic Market Weekly

May 13, 2013 Volume 17 ~ Issue 18 + Sign in to Your Account H IG H LIG H TS SR THREE. TWO. ONE...UPFRONTS 8 A HIspanic Market Weekly special report A Conversation With… Craig Geller As the annual Upfront showcase gets the Hispanic audience isn’t going away… network on broadcast (HMW Archives At nuvoTV, English- underway this week, network executives it’s getting bigger,” says Steve Mandala, 2/27/13. Broadcast TV Ratings Watch). language content is clearly are in overdrive fine-tuning the flashy executive vice president of advertising focused where bicultural presentations that place their upcoming and sales at Univision. “Advertisers first Hispanic networks on the cable side have Latino see themselves, and primetime lineups, productions, and took money to cable and now they’re also delivered strong numbers in 2012 it’s the core of the network’s new platforms before advertisers, media looking at Spanish-language because it’s and so far into 2013. growth and marketing executives and agency buyers. growing and their dollars go further.” strategy. Fox Deportes had a record-breaking The ultimate goal is the same: grab a Leading into the 2013 Upfront the 2012 and in the first week of 2013 set bigger slice of the television advertising consensus is positive: “robust,” “optimistic” all-time highs among both total viewers 4 dollars pie. and “fascinating” are some of the words and viewers 18-49 in total day, primetime used to describe the marketplace. and weekend day viewership, boosted by A Message Although the population numbers and strong growth from its news and soccer And A Chuckle spending power of U.S.