26 -Aida Hurtado J-Lo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

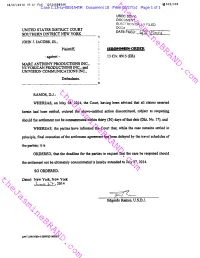

Thejasminebrand.Com Thejasminebrand.Com Case 1:13-Cv-08915-ER Document 14 Filed 05/06/14 Page 1 of 34

theJasmineBRAND.com Case 1:13-cv-08915-ER Document 18 Filed 06/27/14 Page 1 of 1 theJasmineBRAND.com theJasmineBRAND.com theJasmineBRAND.com Case 1:13-cv-08915-ER Document 14 Filed 05/06/14 Page 1 of 34 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK X JOHN J. JACOBS, JR., : : Plaintiff, : : - against - : : Civil Action No. 13 Civ. 8915 (ER) MARC ANTHONY PRODUCTIONS INC., : NUYORICAN PRODUCTIONS INC., and : UNIVISION COMMUNICATIONS INC., : : Defendants. : X theJasmineBRAND.com DEFENDANTS’ MEMORANDUM OF LAW IN SUPPORT OF MOTION TO DISMISS THE COMPLAINT DAVIS WRIGHT TREMAINE LLP theJasmineBRAND.com Elizabeth McNamara Eric J. Feder 1633 Broadway, 27th floor New York, New York 10019 Telephone: (212) 489-8230 Facsimile: (212) 489-8340 Email: [email protected] Attorneys for Defendants Marc Anthony Productions, Inc., Nuyorican Productions, Inc., Univision Communications, Inc. theJasmineBRAND.com Case 1:13-cv-08915-ER Document 14 Filed 05/06/14 Page 2 of 34 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PRELIMINARY STATEMENT .................................................................................................... 1 FACTUAL BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................... 2 A. The Parties .............................................................................................................. 2 B. Plaintiff’s Treatment and Its Alleged Submission to Defendants ........................... 3 C. The Two Works ..................................................................................................... -

PARKER (Tratto Dal Romanzo Flashfire Di Donald E

Indie Pictures s.p.a. Presenta PARKER (tratto dal romanzo Flashfire di Donald E. Westlake) Diretto da : Taylor Hackford Con: Jason Statham, Jennifer Lopez, Nick Nolte, Michael Chiklis Durata: 118’ Data di uscita: 8 maggio 2014 UFFICIO STAMPA Studio Sottocorno - Lorena Borghi Tel. +39 02 20402142 Email [email protected] ; [email protected] [email protected] PARKER – IL CONCEPT Un criminale di professione con un impeccabile codice d'onore è alla ricerca di vendetta contro la banda che gli ha giocato un brutto colpo in PARKER, un grintoso e moderno film noir ambientato nella ricchezza senza pari e il fascino di Palm Beach. Diretto dal premio Oscar Taylor Hackford, PARKER è la riduzione cinematografica di uno dei romanzi più celebri del famoso scrittore Donald E. Westlake, e porta per la prima volta sullo schermo l’antieroe che ne è protagonista. Audace, meticoloso e spietato, Parker (interpretato da Jason Statham) è un esperto di pianificazione e di esecuzione di furti apparentemente impossibili. Ai suoi collaboratori chiede assoluta lealtà e preciso rispetto dei piani. Ma quando la sua ultima rapina ha risvolti mortali a causa della disattenzione di un membro della squadra, Parker rifiuta di unirsi al boss Melander (Michael Chiklis) e alla sua banda per il loro prossimo grande colpo. Non disposti ad accettare un no i criminali aggrediscono Parker, lasciandolo apparentemente morto sul ciglio di una strada deserta. Sopravvissuto all'aggressione e deciso a vendicarsi contro gli uomini che lo hanno tradito, Parker si mette sulle tracce della banda fino a giungere alla sfarzosa Palm Beach. Fingendosi un ricco texano alla ricerca di una casa, incontra Leslie (Jennifer Lopez), un’agente immobiliare dotata di una conoscenza enciclopedica della zona. -

New Approaches Toward Recent Gay Chicano Authors and Their Audience

Selling a Feeling: New Approaches Toward Recent Gay Chicano Authors and Their Audience Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Douglas Paul William Bush, M.A. Graduate Program in Spanish and Portuguese The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Ignacio Corona, Advisor Frederick Luis Aldama Fernando Unzueta Copyright by Douglas Paul William Bush 2013 Abstract Gay Chicano authors have been criticized for not forming the same type of strong literary identity and community as their Chicana feminist counterparts, a counterpublic that has given voice not only to themselves as authors, but also to countless readers who see themselves reflected in their texts. One of the strengths of the Chicana feminist movement is that they have not only produced their own works, but have made sense of them as well, creating a female-to-female tradition that was previously lacking. Instead of merely reiterating that gay Chicano authors have not formed this community and common identity, this dissertation instead turns the conversation toward the reader. Specifically, I move from how authors make sense of their texts and form community, to how readers may make sense of texts, and finally, to how readers form community. I limit this conversation to three authors in particular—Alex Espinoza, Rigoberto González, and Manuel Muñoz— whom I label the second generation of gay Chicano writers. In González, I combine the cognitive study of empathy and sympathy to examine how he constructs affective planes that pull the reader into feeling for and with the characters that he draws. -

Tolono Library CD List

Tolono Library CD List CD# Title of CD Artist Category 1 MUCH AFRAID JARS OF CLAY CG CHRISTIAN/GOSPEL 2 FRESH HORSES GARTH BROOOKS CO COUNTRY 3 MI REFLEJO CHRISTINA AGUILERA PO POP 4 CONGRATULATIONS I'M SORRY GIN BLOSSOMS RO ROCK 5 PRIMARY COLORS SOUNDTRACK SO SOUNDTRACK 6 CHILDREN'S FAVORITES 3 DISNEY RECORDS CH CHILDREN 7 AUTOMATIC FOR THE PEOPLE R.E.M. AL ALTERNATIVE 8 LIVE AT THE ACROPOLIS YANNI IN INSTRUMENTAL 9 ROOTS AND WINGS JAMES BONAMY CO 10 NOTORIOUS CONFEDERATE RAILROAD CO 11 IV DIAMOND RIO CO 12 ALONE IN HIS PRESENCE CECE WINANS CG 13 BROWN SUGAR D'ANGELO RA RAP 14 WILD ANGELS MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 15 CMT PRESENTS MOST WANTED VOLUME 1 VARIOUS CO 16 LOUIS ARMSTRONG LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB JAZZ/BIG BAND 17 LOUIS ARMSTRONG & HIS HOT 5 & HOT 7 LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB 18 MARTINA MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 19 FREE AT LAST DC TALK CG 20 PLACIDO DOMINGO PLACIDO DOMINGO CL CLASSICAL 21 1979 SMASHING PUMPKINS RO ROCK 22 STEADY ON POINT OF GRACE CG 23 NEON BALLROOM SILVERCHAIR RO 24 LOVE LESSONS TRACY BYRD CO 26 YOU GOTTA LOVE THAT NEAL MCCOY CO 27 SHELTER GARY CHAPMAN CG 28 HAVE YOU FORGOTTEN WORLEY, DARRYL CO 29 A THOUSAND MEMORIES RHETT AKINS CO 30 HUNTER JENNIFER WARNES PO 31 UPFRONT DAVID SANBORN IN 32 TWO ROOMS ELTON JOHN & BERNIE TAUPIN RO 33 SEAL SEAL PO 34 FULL MOON FEVER TOM PETTY RO 35 JARS OF CLAY JARS OF CLAY CG 36 FAIRWEATHER JOHNSON HOOTIE AND THE BLOWFISH RO 37 A DAY IN THE LIFE ERIC BENET PO 38 IN THE MOOD FOR X-MAS MULTIPLE MUSICIANS HO HOLIDAY 39 GRUMPIER OLD MEN SOUNDTRACK SO 40 TO THE FAITHFUL DEPARTED CRANBERRIES PO 41 OLIVER AND COMPANY SOUNDTRACK SO 42 DOWN ON THE UPSIDE SOUND GARDEN RO 43 SONGS FOR THE ARISTOCATS DISNEY RECORDS CH 44 WHATCHA LOOKIN 4 KIRK FRANKLIN & THE FAMILY CG 45 PURE ATTRACTION KATHY TROCCOLI CG 46 Tolono Library CD List 47 BOBBY BOBBY BROWN RO 48 UNFORGETTABLE NATALIE COLE PO 49 HOMEBASE D.J. -

Experimental Study on the Impact of the 6+1 Trait Writing Model On

Experimental Study on the Impact of the 6+1 Trait® Writing Model on Student Achievement in Writing Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory This report is part of a series from NWREL to assist in school improvement. Publications are available in five areas: Re-engineering Assists schools, districts, and communities in reshaping rules, roles, structures, and relationships to build capacity for long-term improvement Quality Teaching and Learning Provides resources and strategies for teachers to improve curriculum, instruction, and assessment by promoting professional learning through reflective, collegial inquiry School, Family, and Community Partnerships Promotes child and youth success by working with schools to build culturally responsive partnerships with families and communities Language and Literacy Assists educators in understanding the complex nature of literacy development and identifying multiple ways to engage students in literacy learning that result in highly proficient readers, writers, and speakers Assessment Helps schools identify, interpret, and use data to guide planning and accountability Experimental Study on the Impact of the 6+1 Trait® Writing Model on Student Achievement in Writing Michael Kozlow Peter Bellamy December 2004 Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory 101 SW Main Street, Suite 500 Portland, Oregon 97204 Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory 101 SW Main Street, Suite 500 Portland, Oregon 97204-3213 503-275-9500 www.nwrel.org [email protected] Center for Research, Evaluation, and Assessment Assessment Program © Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory, 2004 All Rights Reserved This project has been funded at least in part with Federal funds from the U.S. Department of Education under contract number ED-01-CO-0013. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. -

G8sz9 (Download Free Pdf) the Temptation: a Kindred Novel Online

g8sz9 (Download free pdf) The Temptation: A Kindred Novel Online [g8sz9.ebook] The Temptation: A Kindred Novel Pdf Free Par Alisa Valdes *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook Détails sur le produit Publié le: 2012-04-24Sorti le: 2012-04-24Format: Ebook Kindle | File size: 28.Mb Par Alisa Valdes : The Temptation: A Kindred Novel before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Temptation: A Kindred Novel: Commentaires clientsCommentaires clients les plus utiles0 internautes sur 0 ont trouvé ce commentaire utile. Quand les esprits s'en mêlent...Par FleurJe suis surprise de lire autant d'avis négatifs, car l'histoire est sympathique et agréable à suivre. J'ai parcouru pour comparer l'autre version proposée par l'auteur(e) quoique plus détaillée, elle apporte une vision plus élargie des personnages qui sont moins stéréotypés mais le fond reste le même... Perso, j'ai aimé les deux versions mais ma préférence pencherait nettement pour ce livre-ci justement de par sa simplicité.Tout ce que l'on demande à un livre c'est de nous faire voyager et celui-ci remplit son office. J'espère malgré tout qu'il y aura une suite, cela serait dommage de s'arrêter là... Alors, trés chère auteur(e) reprenait vite votre plume, nous attendons avec impatience le retour de Shane et Travis ! Présentation de l'éditeurHis touch was electric.His eyes were magnetic.His lips were a temptation. .But was he real?Shane is near death after crashing her car on a long stretch of empty highway in rural New Mexico when she is miraculously saved by a mysterious young man who walks out of nowhere. -

An Investigation of the Impact of the 6+1 Trait Writing Model on Grade 5

NCEE 2012-4010 U. S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION An Investigation of the Impact of the 6+1 Trait Writing Model on Grade 5 Student Writing Achievement An Investigation of the Impact of the 6+1 Trait Writing Model on Grade 5 Student Writing Achievement Final Report December 2011 Authors: Michael Coe Cedar Lake Research Group Makoto Hanita Education Northwest Vicki Nishioka Education Northwest Richard Smiley Education Northwest Project Officer: Ok-Choon Park Institute of Education Sciences NCEE 2012–4010 U.S. Department of Education U.S. Department of Education Arne Duncan Secretary Institute of Education Sciences John Q. Easton Director National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance Rebecca A. Maynard Commissioner December 2011 This report was prepared for the National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, under contract ED-06-CO-0016 with Regional Educational Laboratory Northwest administered by Education Northwest. IES evaluation reports present objective information on the conditions of implementation and impacts of the programs being evaluated. IES evaluation reports do not include conclusions or recommendations or views with regard to actions policymakers or practitioners should take in light of the findings in the report. This report is in the public domain. Authorization to reproduce it in whole or in part is granted. While permission to reprint this publication is not necessary, the citation should read: Coe, Michael, Hanita, Makoto, Nishioka, Vicki, and Smiley, Richard. (2011). An investigation of the impact of the 6+1 Trait Writing model on grade 5 student writing achievement (NCEE 2012–4010). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. -

Emmy Nominations

2021 Emmy® Awards 73rd Emmy Awards Complete Nominations List Outstanding Animated Program Big Mouth • The New Me • Netflix • Netflix Bob's Burgers • Worms Of In-Rear-Ment • FOX • 20th Century Fox Television / Bento Box Animation Genndy Tartakovsky's Primal • Plague Of Madness • Adult Swim • Cartoon Network Studios The Simpsons • The Dad-Feelings Limited • FOX • A Gracie Films Production in association with 20th Television Animation South Park: The Pandemic Special • Comedy Central • Central Productions, LLC Outstanding Short Form Animated Program Love, Death + Robots • Ice • Netflix • Blur Studio for Netflix Maggie Simpson In: The Force Awakens From Its Nap • Disney+ • A Gracie Films Production in association with 20th Television Animation Once Upon A Snowman • Disney+ • Walt Disney Animation Studios Robot Chicken • Endgame • Adult Swim • A Stoopid Buddy Stoodios production with Williams Street and Sony Pictures Television Outstanding Production Design For A Narrative Contemporary Program (One Hour Or More) The Flight Attendant • After Dark • HBO Max • HBO Max in association with Berlanti Productions, Yes, Norman Productions, and Warner Bros. Television Sara K. White, Production Designer Christine Foley, Art Director Jessica Petruccelli, Set Decorator The Handmaid's Tale • Chicago • Hulu • Hulu, MGM, Daniel Wilson Productions, The Littlefield Company, White Oak Pictures Elisabeth Williams, Production Designer Martha Sparrow, Art Director Larry Spittle, Art Director Rob Hepburn, Set Decorator Mare Of Easttown • HBO • HBO in association with wiip Studios, TPhaeg eL o1w Dweller Productions, Juggle Productions, Mayhem Mare Of Easttown • HBO • HBO in association with wiip Studios, The Low Dweller Productions, Juggle Productions, Mayhem and Zobot Projects Keith P. Cunningham, Production Designer James F. Truesdale, Art Director Edward McLoughlin, Set Decorator The Undoing • HBO • HBO in association with Made Up Stories, Blossom Films, David E. -

The Derailment of Feminism: a Qualitative Study of Girl Empowerment and the Popular Music Artist

THE DERAILMENT OF FEMINISM: A QUALITATIVE STUDY OF GIRL EMPOWERMENT AND THE POPULAR MUSIC ARTIST A Thesis by Jodie Christine Simon Master of Arts, Wichita State University, 2010 Bachelor of Arts. Wichita State University, 2006 Submitted to the Department of Liberal Studies and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts July 2012 @ Copyright 2012 by Jodie Christine Simon All Rights Reserved THE DERAILMENT OF FEMINISM: A QUALITATIVE STUDY OF GIRL EMPOWERMENT AND THE POPULAR MUSIC ARTIST The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this thesis for form and content, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts with a major in Liberal Studies. __________________________________________________________ Jodie Hertzog, Committee Chair __________________________________________________________ Jeff Jarman, Committee Member __________________________________________________________ Chuck Koeber, Committee Member iii DEDICATION To my husband, my mother, and my children iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my adviser, Dr. Jodie Hertzog, for her patient and insightful advice and support. A mentor in every sense of the word, Jodie Hertzog embodies the very nature of adviser; her council was very much appreciated through the course of my study. v ABSTRACT “Girl Power!” is a message that parents raising young women in today’s media- saturated society should be able to turn to with a modicum of relief from the relentlessly harmful messages normally found within popular music. But what happens when we turn a critical eye toward the messages cloaked within this supposedly feminist missive? A close examination of popular music associated with girl empowerment reveals that many of the messages found within these lyrics are frighteningly just as damaging as the misogynistic, violent, and explicitly sexual ones found in the usual fare of top 100 Hits. -

Freestyle Rap Practices in Experimental Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 3-2-2017 On My Grind: Freestyle Rap Practices in Experimental Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy Evan Nave Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, Creative Writing Commons, Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Educational Methods Commons Recommended Citation Nave, Evan, "On My Grind: Freestyle Rap Practices in Experimental Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 697. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/697 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ON MY GRIND: FREESTYLE RAP PRACTICES IN EXPERIMENTAL CREATIVE WRITING AND COMPOSITION PEDAGOGY Evan Nave 312 Pages My work is always necessarily two-headed. Double-voiced. Call-and-response at once. Paranoid self-talk as dichotomous monologue to move the crowd. Part of this has to do with the deep cuts and scratches in my mind. Recorded and remixed across DNA double helixes. Structurally split. Generationally divided. A style and family history built on breaking down. Evidence of how ill I am. And then there’s the matter of skin. The material concerns of cultural cross-fertilization. Itching to plant seeds where the grass is always greener. Color collaborations and appropriations. Writing white/out with black art ink. Distinctions dangerously hidden behind backbeats or shamelessly displayed front and center for familiar-feeling consumption. -

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION

Exhibit 52.1 Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, DC ,QWKH0DWWHURI $SSOLFDWLRQVRI&RPFDVW&RUSRUDWLRQ 0%'RFNHW1R *HQHUDO(OHFWULF&RPSDQ\ DQG1%&8QLYHUVDO,QF )RU&RQVHQWWR$VVLJQ/LFHQVHVDQG 7UDQVIHU&RQWURORI/LFHQVHHV ANNUAL REPORT OF COMPLIANCE WITH TRANSACTION CONDITIONS Comcast Corporation NBCUniversal Media,LLC 1HZ-HUVH\$YHQXH1: 6XLWH :DVKLQJWRQ'& )HEUXDU\ TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 3$5721(&203/,$1&(29(59,(: $ &RPFDVW7UDQVDFWLRQ&RPSOLDQFH7HDP % 1%&8QLYHUVDO7UDQVDFWLRQ&RPSOLDQFH7HDP & 7UDLQLQJRIWKH5HOHYDQW%XVLQHVV8QLWV ' &RPSOLDQFH0RQLWRULQJDQG$XGLWLQJ 3$577:2&203/,$1&(:,7+63(&,),&&21',7,216 , '(),1,7,216 ,, $&&(6672&1%&8352*5$00,1* ,,, &$55,$*(2)81$)),/,$7('9,'(2352*5$00,1* 1RQ'LVFULPLQDWRU\&DUULDJH 1HLJKERUKRRGLQJ 1HZ,QGHSHQGHQW1HWZRUNV 3URJUDP&DUULDJH&RPSODLQWV ,9 21/,1(&21',7,216 $ 2QOLQH3URJUDP$FFHVV5HTXLUHPHQWVDQG3URFHGXUHV % ([FOXVLYLW\:LQGRZLQJ & &RQWLQXHG$FFHVVWR2QOLQH&RQWHQWDQG+XOX &RQWLQXHG3URJUDPPLQJRQ1%&FRP 3UHH[LVWLQJ29''HDOV 3URYLVLRQRI&RQWHQWWR+XOX 5HOLQTXLVKPHQWRI&RQWURORYHU+XOX ' 6WDQGDORQH%URDGEDQG,QWHUQHW$FFHVV6HUYLFH ³%,$6´ 3URYLVLRQRI6WDQGDORQH%,$6 9LVLEO\2IIHUDQG$FWLYHO\0DUNHW5HWDLO6WDQGDORQH%,$6 %,$6$QQXDO5HSRUW ( 2WKHU%,$6&RQGLWLRQV 6SHFLDOL]HG6HUYLFH5HTXLUHPHQWV 0ESV2IIHULQJ ) ³6SHFLDOL]HG6HUYLFH´RQ&RPFDVW6HW7RS%R[HV ³67%V´ * 8QIDLU3UDFWLFHV 9 127,&(2)&21',7,216 9, 5(3/$&(0(172)35,25&21',7,216 9,, &200(5&,$/$5%,75$7,215(0('< 9,,, 02',),&$7,21727+($$$58/(6)25$5%,75$7,21 ,; %52$'&$67&21',7,216 ; ',9(56,7<&21',7,216 7HOHPXQGR0XOWLFDVW&KDQQHO 7HOHPXQGRDQGPXQ3URJUDPPLQJRQ&RPFDVW2Q'HPDQG -

Index of /Sites/Default/Al Direct/2006/July

AL Direct, July 5, 2006 Contents: U.S. & World News ALA News Booklist Online New Orleans Update Division News Awards Seen Online Actions & Answers July 5, 2006 Poll AL Direct is a free electronic newsletter e-mailed every Wednesday to personal Datebook members of the American Library Association. AL Direct FAQ Net neutrality loses a round in the Senate Supporters of net neutrality were dealt a second blow June 28 when the Senate Commerce Committee rejected by an 11–11 tie vote a bill that mandated equal access to online content for all customers. The defeated Internet Freedom Preservation Act, sponsored by Sen. Olympia Snowe (R- Maine) and Byron Dorgan (D-N.Dak.), would have prohibited network operators from charging tiered fees to either content providers or recipients of bandwidth-intensive applications.... 10,000 EPA scientists protest elimination of libraries The presidents of 17 locals of the American Federation of Federal Employees, the National Treasury Employees Union, the National Association of Government Employees, and Engineers and Scientists of California have signed a letter asking Congress to halt the closure of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s network of research libraries.... Use ALSC’s Great Web Mayor makes libraries permanent line item Sites for Kids page to New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg has agreed to locate kid-friendly “baseline” funding for the library and two other programs, online information on making them permanent allocations in the city’s annual animals, art, history, budget. In the past, libraries have been a part of what math, and other pundits have dubbed the “budget dance,” in which the mayor subjects.