Although It Relegates Geography to a Secondary Status, Nova Scotia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Micmac Migration to Western Newfoundland

MICMAC MIGRATION TO WESTERN NEWFOUNDLAND DENNIS A. BARTELS Department of Anthropology Sir Wilfred Grenfell College Memorial University of Newfoundland Corner Brook, Newfoundland Canada, and OLAF UWE JANZEN Department of History Sir Wilfred Grenfell College Memorial University of Newfoundland Corner Brook, Newfoundland Canada, ABSTRACT / RESUME The Micmac of Cape Breton are known to have had a long history of seasonal contact with Newfoundland. It is generally accepted that they resided there permanently by the early 19th century. The authors review the available evidence and conclude that the permanent occupation of Newfoundland by the Micmac began in the 1760s. On sait que les Micmac de cap-Breton ont eu une longue histoire du contact saisonnier avec la Terre-Neuve. Il est généralement admis qu'ils y habitèrent en permanence au début du XIXe siècle. Les auteurs examinent l'évidence disponible et concluent que l'occupation permanente de la Terre-Neuve par les Micmac a commencé dans les années 1760. 72 Dennis A. Bartel/Olaf Uwe Janzen INTRODUCTION It is generally conceded that the Micmac of Cape Breton Island were a maritime-adapted people with sufficient seafaring skills to extend their territorial range as far into the Gulf of St. Lawrence as the Magdalen Islands and as far east as St. Pierre and Miquelon.1 By the eighteenth century, the Micmac were able to maintain a persistent presence in southern and southwestern Newfoundland. Some scholars have concluded from this that southwestern Newfoundland could have been a regular part of the territorial range of the Cape Breton Micmac since prehistoric times.2 In the absence of archaeological evidence to support such a conclusion, others, such as Marshall (1988) and Upton (1979:64) are unwilling to concede more than a seasonal exploitation of Newfoundland. -

Discussion on the Newfoundland and Labrador Inshore Fishery

Discussion on the Newfoundland and Labrador Inshore Fishery What We Heard - A Summary of Comments from Public Discussions on the Future of Newfoundland and Labrador’s Inshore Fishery. © Her Majesty the Queen in the Right of Canada, 2020. PDF: Dept. catalogue number: DFO/2019-2020 GC catalogue number: Fs114-19/2020E-PDF ISBN: 978-0-660-33721-0 The cover is a photo of the Community of Belleoram, Newfoundland and Labrador Photo by Dan Ficken, Environmental Officer Executive Summary Executive Summary A total of 18 inshore fishery consultation meetings were held throughout Newfoundland and Labrador during the winter and spring of 2019. This was the second series of open consultations with inshore fish harvesters, the first series took place in the fall and winter of 2017-18. The purpose of these consultations was to provide a forum for individual harvesters and their representatives to raise concerns and ask questions During the meetings on a wide range of fishery management topics. The meetings featured fish harvesters asked flexible agendas and allowed significant harvester participation. questions and offered During the meetings fish harvesters asked questions and offered their their perspectives about perspectives about various aspects of fisheries management and science. Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) also took the opportunity to address various aspects of the questions and concerns raised during the previous consultations in fisheries management 2017-18. and science. Topics discussed and questions raised in the meetings centred upon five general themes: • The timing of fishery openings and closures; • The way fishery overlap privileges near the boundaries of major fishing zones are managed; • Sharing arrangements for fish stocks, particularly those in which harvesters from neighbouring regions are allocated greater shares than harvesters from Newfoundland and Labrador; • Permitting more buddy-up arrangements; and • Vessel length restrictions and vessel replacement rules. -

Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador

Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador ii Oceans, Habitat and Species at Risk Publication Series, Newfoundland and Labrador Region No. 0008 March 2009 Revised April 2010 Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador Prepared by 1 Intervale Associates Inc. Prepared for Oceans Division, Oceans, Habitat and Species at Risk Branch Fisheries and Oceans Canada Newfoundland and Labrador Region2 Published by Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Newfoundland and Labrador Region P.O. Box 5667 St. John’s, NL A1C 5X1 1 P.O. Box 172, Doyles, NL, A0N 1J0 2 1 Regent Square, Corner Brook, NL, A2H 7K6 i ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2011 Cat. No. Fs22-6/8-2011E-PDF ISSN1919-2193 ISBN 978-1-100-18435-7 DFO/2011-1740 Correct citation for this publication: Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 2011. Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador. OHSAR Pub. Ser. Rep. NL Region, No.0008: xx + 173p. ii iii Acknowledgements Many people assisted with the development of this report by providing information, unpublished data, working documents, and publications covering the range of subjects addressed in this report. We thank the staff members of federal and provincial government departments, municipalities, Regional Economic Development Corporations, Rural Secretariat, nongovernmental organizations, band offices, professional associations, steering committees, businesses, and volunteer groups who helped in this way. We thank Conrad Mullins, Coordinator for Oceans and Coastal Management at Fisheries and Oceans Canada in Corner Brook, who coordinated this project, developed the format, reviewed all sections, and ensured content relevancy for meeting GOSLIM objectives. -

The Hitch-Hiker Is Intended to Provide Information Which Beginning Adult Readers Can Read and Understand

CONTENTS: Foreword Acknowledgements Chapter 1: The Southwestern Corner Chapter 2: The Great Northern Peninsula Chapter 3: Labrador Chapter 4: Deer Lake to Bishop's Falls Chapter 5: Botwood to Twillingate Chapter 6: Glenwood to Gambo Chapter 7: Glovertown to Bonavista Chapter 8: The South Coast Chapter 9: Goobies to Cape St. Mary's to Whitbourne Chapter 10: Trinity-Conception Chapter 11: St. John's and the Eastern Avalon FOREWORD This book was written to give students a closer look at Newfoundland and Labrador. Learning about our own part of the earth can help us get a better understanding of the world at large. Much of the information now available about our province is aimed at young readers and people with at least a high school education. The Hitch-Hiker is intended to provide information which beginning adult readers can read and understand. This work has a special feature we hope readers will appreciate and enjoy. Many of the places written about in this book are seen through the eyes of an adult learner and other fictional characters. These characters were created to help add a touch of reality to the printed page. We hope the characters and the things they learn and talk about also give the reader a better understanding of our province. Above all, we hope this book challenges your curiosity and encourages you to search for more information about our land. Don McDonald Director of Programs and Services Newfoundland and Labrador Literacy Development Council ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank the many people who so kindly and eagerly helped me during the production of this book. -

Piping Plover (Charadrius Melodus Melodus) in Canada

Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series Recovery Strategy for the Piping Plover (Charadrius melodus melodus) in Canada Piping Plover, melodus subspecies 2012 Recommended citation: Environment Canada. 2012. Recovery Strategy for the Piping Plover (Charadrius melodus melodus) in Canada. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Environment Canada, Ottawa. v + 29 pp. For copies of the recovery strategy, or for additional information on species at risk, including COSEWIC Status Reports, residence descriptions, action plans, and other related recovery documents, please visit the Species at Risk (SAR) Public Registry (www.sararegistry.gc.ca). Cover illustration: John Chardine © 2010 Également disponible en français sous le titre « Programme de rétablissement du Pluvier siffleur (Charadrius melodus melodus) au Canada » © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 2012. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-100-20168-9 Catalogue no. En3-4/9-2012E-PDF Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source. Recovery Strategy for the Piping Plover, melodus subspecies 2012 PREFACE The federal, provincial, and territorial government signatories under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996) agreed to establish complementary legislation and programs that provide for effective protection of species at risk throughout Canada. Under the Species at Risk Act (S.C. 2002, c.29) (SARA), the federal competent ministers are responsible for the preparation of recovery strategies for listed Extirpated, Endangered, and Threatened species and are required to report on progress within five years. The Minister of the Environment and the Minister responsible for the Parks Canada Agency are the competent ministers for the recovery of the Piping Plover, melodus subspecies and have prepared this strategy, as per section 37 of SARA. -

CABOT's LANDFALL by C

_J_ CABOT'S LANDFALL By C. B. FERGUSSON HILE the profound importance and the far-reaching consequences of the discovery of N ortb America by John Cabot in 1497 have long been realized, and in W some measure recognized, his landfall in the New World still remains unmarked. T hat is actually so. But it in dicates neither a lack of interest in doing honour to a distin guished navigator for his outstanding services, nor a paucity of those who have urged the marking of his landfall or advanced claims with respect to its site. His name and his fame are per petuated by Cabot Strait, which separates Cape Breton I sland :..... r- from Newfoundland, by the Cabot Trail, with its unsurt>assed :., , scenic splendour, in Cape Breton Island, and by Cabot 'l'ower on Signal Hill, at St. John's in Newfoundland. It is very fitting that Cabot's a.ctivities should be so com memorated in both Cape Breton Island and Newfoundland, for his voyages had great significance for each. Yet these me morials, through their different locations, may also indicate the crux of the Cabotian controversy: there is still a lack of un animity with respect to the site of Cabot's landfall in 1497. There are some who would claim it for Cape Breton Island, as well as others who would attribute it to Newfoundland or Labra dor. And now that Newfoundland is a part of the Canadian nation, these rival claims have been revived, the evidence has been re-considered and re-sifted, and, if it is now possible, a decision should be reached on this matter. -

A Home for Nature: Protected Areas Plan for the Island of Newfoundland

A Home for Nature Protected Areas Plan for the Island of Newfoundland Acknowledgements This Protected Areas Plan for the Island of Newfoundland is the result of over 25 years of science advice, conservation planning, reserve site selection and assessment, resource industry assessments, discussions and negotiations. Although the process was lengthy and challenging, citizens should feel confident that the result is a well-considered and balanced contribution to sustainability of our province: for our environmental, economic and social well-being. The Wilderness and Ecological Reserves Advisory Council would like to acknowledge and thank all those who had a hand in development of the Plan: the Protected Areas Association; the Natural Areas System Plan Committee (1995-1996); the Natural Areas Plan Conflict Resolution Committee (2002-2003); the Western Newfoundland Model Forest; the Natural Areas System Plan Working Group (2006-2008); the Natural Areas System Plan Deputy Minister Steering Committee; past members of the Wilderness and Ecological Reserves Advisory Council; interdepartmental ad hoc committees (2000-2019) and staff from provincial government departments representing tourism, municipalities, forestry, mining, Indigenous affairs, environment and wildlife, that worked so hard over the years to bring this Plan forward. Finally, WERAC would like to thank all the people of Newfoundland and Labrador who have been involved in the establishment of our province’s existing wilderness and ecological reserves. Citation: Wilderness and Ecological Reserves Advisory Council. A Home for Nature: Protected Areas Plan for the Island of Newfoundland. 2020. Available in alternate format upon request. The maps in this document are for illustrative purposes only. Front Cover/Back Cover Arches Provincial Park i Highlands of St. -

Seeing the Light: Report on Staffed Lighthouses in Newfoundland and Labrador and British Columbia

SEEING THE LIGHT: REPORT ON STAFFED LIGHTHOUSES IN NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR AND BRITISH COLUMBIA Report of the Standing Senate Committee on Fisheries and Oceans The Honourable Fabian Manning, Chair The Honourable Elizabeth Hubley, Deputy Chair October 2011 (first published in December 2010) For more information please contact us by email: [email protected] by phone: (613) 990-0088 toll-free: 1 800 267-7362 by mail: Senate Committee on Fisheries and Oceans The Senate of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, K1A 0A4 This report can be downloaded at: http://senate-senat.ca Ce rapport est également disponible en français. MEMBERSHIP The Honourable Fabian Manning, Chair The Honourable Elizabeth Hubley, Deputy Chair and The Honourable Senators: Ethel M. Cochrane Dennis Glen Patterson Rose-Marie Losier-Cool Rose-May Poirier Sandra M. Lovelace Nicholas Vivienne Poy Michael L. MacDonald Nancy Greene Raine Donald H. Oliver Charlie Watt Ex-officio members of the committee: The Honourable Senators James Cowan (or Claudette Tardif) Marjory LeBreton, P.C. (or Claude Carignan) Other Senators who have participated on this study: The Honourable Senators Andreychuk, Chaput, Dallaire, Downe, Marshall, Martin, Murray, P.C., Rompkey, P.C., Runciman, Nancy Ruth, Stewart Olsen and Zimmer. Parliamentary Information and Research Service, Library of Parliament: Claude Emery, Analyst Senate Committees Directorate: Danielle Labonté, Committee Clerk Louise Archambeault, Administrative Assistant ORDER OF REFERENCE Extract from the Journals of the Senate, Sunday, June -

Community Files in the Centre for Newfoundland Studies

Community Files in the Centre for Newfoundland Studies A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | 0 | P | Q-R | S | T | U-V | W | X-Y-Z A Abraham's Cove Adams Cove, Conception Bay Adeytown, Trinity Bay Admiral's Beach Admiral's Cove see Port Kirwan Aguathuna Alexander Bay Allan’s Island Amherst Cove Anchor Point Anderson’s Cove Angel's Cove Antelope Tickle, Labrador Appleton Aquaforte Argentia Arnold's Cove Aspen, Random Island Aspen Cove, Notre Dame Bay Aspey Brook, Random Island Atlantic Provinces Avalon Peninsula Avalon Wilderness Reserve see Wilderness Areas - Avalon Wilderness Reserve Avondale B (top) Baccalieu see V.F. Wilderness Areas - Baccalieu Island Bacon Cove Badger Badger's Quay Baie Verte Baie Verte Peninsula Baine Harbour Bar Haven Barachois Brook Bareneed Barr'd Harbour, Northern Peninsula Barr'd Islands Barrow Harbour Bartlett's Harbour Barton, Trinity Bay Battle Harbour Bauline Bauline East (Southern Shore) Bay Bulls Bay d'Espoir Bay de Verde Bay de Verde Peninsula Bay du Nord see V.F. Wilderness Areas Bay L'Argent Bay of Exploits Bay of Islands Bay Roberts Bay St. George Bayside see Twillingate Baytona The Beaches Beachside Beau Bois Beaumont, Long Island Beaumont Hamel, France Beaver Cove, Gander Bay Beckford, St. Mary's Bay Beer Cove, Great Northern Peninsula Bell Island (to end of 1989) (1990-1995) (1996-1999) (2000-2009) (2010- ) Bellburn's Belle Isle Belleoram Bellevue Benoit's Cove Benoit’s Siding Benton Bett’s Cove, Notre Dame Bay Bide Arm Big Barasway (Cape Shore) Big Barasway (near Burgeo) see -

An Eastern Micmac Domain of Islands

An Eastern Micmac Domain of Islands CHARLES A. MARTIJN Ministere des Affaires cullurelles, Quebec Introduction The Micmac Indians of Eastern Canada inhabit a region that borders the lower half of the Gulf of St. Lawrence.1 Their homeland includes portions of the Gaspe Peninsula and New Brunswick, all of Prince Edward Island and mainland Nova Scotia, as well as Cape Breton and parts of southern Newfoundland. Although the boundaries of this traditional territory cannot be determined with any precision because of fluctuations through time, it may have covered as much as 121,760 square kilometres, or about the size of Tunisia. An overview of Micmac culture and society is provided by Hoffman (1955), Nietfeld (1981), Passchier (1985) and Wallis and Wallis (1955). An extensive coastline permitted easy access to aquatic fauna — sea- mammals, fish, waterfowl and invertebrates — which are abundant in the gulf of St. Lawrence area. As a result, the Micmac were probably the most maritime-adapted of all Algonquian groups. Nevertheless, for survival dur ing the winter months they had to depend to a much greater extent on land animals such as moose, caribou, deer and beaver. Some scholars have depicted them as spending up to 10 months of the year obtaining 90% of their food requirements from coastal zones and the sea (Hoffman 1955:230- 236; Nietfeld 1981:360-363). Recent reviews of archaeological and ethno historical data, however, indicate a greater use of terrestrial fauna than has hitherto been acknowledged, and point to the need for a more intensive consideration of regional variation in available resources and subsistence strategies (Nash and Miller 1987; see also Burley 1981 and Clermont 1986). -

The British American Navigator, Or, Sailing Directory for the Island And

Tin-: >"» -I BRITISH AMERICAN NAVIGATOR; -V, - OH SAILING DIRECTORY FOR THE ISLAND AND BANKS OF NEWFOUNDLAND, THE GULF AND RIVER OF ST. LAWRENCE, Breton Ssilanlr, M NOVA SCOTIA, THE RAY OF FUNDY, AND THE COASTS THENCE TO THE RIVEll PENOBSCOT, &c. ^ I i i i OniOINALLY COMPOSED By JOHN PURDY, Hydrographer; AND COMPLETED, FROM A GREAT • VARIETY OV DOCUMENTS, PUHUC AND PRIVATE, By ALEX. G. FINDLAY. ^ A LONDON: PRINTED FOR R. H. LAURIE, CHAKT-SELLER TO THE ADMIRALTY, THE HON. CORPORATION OF TRINITY-HOUSE, kc i! No. 53, FLEET STREET. 1843. i>_ " •'*•.'?•>. : ->'t ^\^jr' ;:iii2£aa£; .i.":. rriar- r._. — 187056 y ADVERTISEMENT. The following Charts will be found particularly adapted to this Work, and are distinguished by the seal, as in the title-page : 1. A GENERAL CHART of the ATLANTIC OCEAN, according to the Observa- lions, Surveys, and Determinations, of the most eminent Navigators, British and Foreign; from a Combination of which the whole has been deduced, by John Purdy. With parti- cular Plans of the Roadstead of Angra, Terceira, Ponta-Delgada, St. Michael's, of the Channel between Fayal and Pico, Santa-Cruz to Funchal, &c. On four large sheets. tit With additions to the present time. \6s. sen ',• The new Chart of the Atlantic may be had in two parts, one containing the northern and the other the southern sheets ; being a form extremely convenient for use at sea. 2. The ATLANTIC, or WESTERN OCEAN, with Hudson's Bay and other adjacent Seas ; including the Coasts of Europe, Africa, and America, from sixty-five degrees of North Latitude to the Equator ; but without the particular Plans above mentioned. -

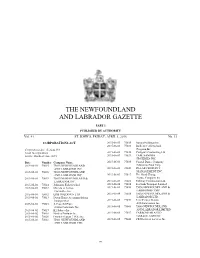

The Newfoundland and Labrador Gazette

THE NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR GAZETTE PART I PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY Vol. 91 ST. JOHN’S, FRIDAY, APRIL 1, 2016 No. 13 CORPORATIONS ACT 2015-06-03 75035 Aurora Holdings Inc. 2015-06-03 75033 Ballicatter Afterschool Corporations Act - Section 393 Program Inc. Local Incorporations 2015-06-03 75032 Cadigan's Contracting Ltd. For the Month of: June 2015 2015-06-03 75029 CAPE SANDRA FISHERIES INC. Date Number Company Name 2015-06-03 75030 Coastal Dance Company 2015-06-01 75015 75015 NEWFOUNDLAND Education Fund Corp. AND LABRADOR INC. 2015-06-03 75041 PILLAR PROPERTY 2015-06-01 75016 75016 NEWFOUNDLAND MANAGEMENT INC. AND LABRADOR INC. 2015-06-03 75027 The Good Change 2015-06-01 75019 75019 NEWFOUNDLAND & Picture Company Inc. LABRADOR INC. 2015-06-03 75028 Pathway Construction Ltd. 2015-06-01 75014 Johnson's Fisheries Ltd. 2015-06-04 75034 Sea Link Transport Limited 2015-06-01 75022 Mama's in Action 2015-06-04 75036 75036 NEWFOUNDLAND & Committee Inc. LABRADOR CORP. 2015-06-01 75012 LDB HOLDINGS LTD. 2015-06-04 75038 75038 NEWFOUNDLAND & 2015-06-01 75013 Down Home Accommodations LABRADOR LTD. Incorporated 2015-06-04 75039 Feral Felines Rescue 2015-06-02 75023 A Peaceful Place & Rehabilitation Inc. Animal Sanctuary Inc. 2015-06-05 75046 75046 NEWFOUNDLAND 2015-06-02 75017 K2 Subsea Inc. AND LABRADOR LIMITED 2015-06-02 75018 NorSea Products Inc. 2015-06-05 75047 CARBONEAR AUTO 2015-06-02 75020 Frontier Season 1 (NL) Inc. GARAGE LIMITED 2015-06-03 75031 75031 NEWFOUNDLAND 2015-06-05 75040 CK Electrical Services Inc.