Behavioral Economics and Paternalism Abstract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Behind Behavioral Economic Man: the Methods and Conflicts Between Two Perspectives

Behind Behavioral Economic Man: The Methods and Conflicts Between Two Perspectives Rafael Nunes Teixeira Mestre em Economia pela UnB Daniel Fernando de Souza Mestrando em Desenvolvimento Econômico pela UFPR Keywords: behavioral economics methods, Kahneman and Tversky, Gigerenzer and the ABC Research Group Behind Behavioral Economic Man: The Methods and Conflicts Between Two Perspectives Abstract: This work analyzes the methods of research in decision-making of behavioral economists Kahneman and Tversky (K&T) and one of their main critics, Gigerenzer and the ABC Group. Our aim was to explain differences between these two approaches of BE by examining the procedure used by them to search for the cognitive processes involved in choice. We identified similarities between K&T and the mainstream economics methods that may explain some of the differences with their critics’ approach. We conclude with a discussion of how advances in BE, such as Nudges and Choice Architecture may take advantage of complementarities in these perspectives. Keywords: behavioral economics methods, Kahneman and Tversky, Gigerenzer and the ABC Research Group 1 Introduction Human behavior is a fundamental component of economics and is usually described and interpreted by the Rational Choice Theory (RCT). From Bernoulli to Kreps, the RCT has assumed many different forms and undergone a lot of change in its long history. One key aspect (Sen 2002, 2009) of RCT is the use of logical constructions to describe man as a rational decision maker1. In this view, choices and preferences must be consistent and follow regularities (e.g. completeness and transitivity, α and β (Sen 1971)) and statistical norms (e.g. -

The Representation of Judgment Heuristics and the Generality Problem

The Representation of Judgment Heuristics and the Generality Problem Carole J. Lee ([email protected]) Department of Philosophy, 50 College Street South Hadley, MA 01033 USA Abstract that are inappropriately characterized and should not be used in the epistemic evaluation of belief. Second, In his debates with Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, Gerd Gigerenzer puts forward a stricter standard for the Gigerenzer’s critiques of Daniel Kahneman and Amos proper representation of judgment heuristics. I argue that Tversky’s judgment heuristics help to recast the generality Gigerenzer’s stricter standard contributes to naturalized problem in naturalized epistemology in constructive ways. epistemology in two ways. First, Gigerenzer’s standard can be In the first part of this paper, I will argue that naturalized used to winnow away cognitive processes that are epistemologists and cognitive psychologists like Gigerenzer inappropriately characterized and should not be used in the have explanatory goals and conundrums in common: in epistemic evaluation of belief. Second, Gigerenzer’s critique helps to recast the generality problem in naturalized particular, both seek to explain the production and epistemic epistemology and cognitive psychology as the methodological status of beliefs by referring to the reliable cognitive problem of identifying criteria for the appropriate processes from which they arise; and both face the specification and characterization of cognitive processes in generality problem in trying to do so. Gigerenzer helps to psychological explanations. I conclude that naturalized address the generality problem by proposing a stricter epistemologists seeking to address the generality problem standard for the characterization of cognitive processes. should turn their focus to methodological questions about the This stricter standard disqualifies some judgment heuristics proper characterization of cognitive processes for the purposes of psychological explanation. -

Bounded Rationality: Models of Fast and Frugal Inference

Published in: Swiss Journal of Economics and Statistics, 133 (2/2), 1997, 201–218. © 1997 Peter Lang, 0303-9692. Bounded Rationality: Models of Fast and Frugal Inference Gerd Gigerenzer1 Max Planck Institute for Psychological Research, Munich, Germany Humans and other animals need to make inferences about their environment under constraints of limited time, knowledge, and computational capacities. However, most theories of inductive infer- ences model the human mind as a supercomputer like a Laplacean demon, equipped with unlim- ited time, knowledge, and computational capacities. In this article I review models of fast and frugal inference, that is, satisfi cing strategies whose task is to infer unknown states of the world (without relying on computationaly expensive procedures such as multiple regression). Fast and frugal inference is a form of bounded rationality (Simon, 1982). I begin by explaining what bounded rationality in human inference is not. 1. Bounded Rationality is Not Irrationality In his chapter in John Kagel and Alvin Roth’s Handbook of Experimental Economics (1995), Colin Camerer explains that “most research on individual decision making has taken normative theo- ries of judgment and choice (typically probability rules and utility theories) as null hypotheses about behavior,” and has labeled systematic deviations from these norms “cognitive illusions” (p. 588). Camerer continues, “The most fruitful, popular alternative theories spring from the idea that limits on computational ability force people to use simplifi ed procedures or ‘heuristics’ that cause systematic mistakes (biases) in problem solving, judgment, and choice. The roots of this approach are in Simon’s (1955) distinction between substantive rationality (the result of norma- tive maximizing models) and procedural rationality.” (p. -

Laplace's Theories of Cognitive Illusions, Heuristics, and Biases∗ 1

Laplace's theories of cognitive illusions, heuristics, and biases∗ Joshua B. Millery Andrew Gelmanz 25 Mar 2018 For latest version, click here: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3149224 Abstract In his book from the early 1800s, Essai Philosophique sur les Probabilit´es, the mathematician Pierre-Simon de Laplace anticipated many ideas developed in the 1970s in cognitive psychology and behavioral economics, explaining human tendencies to deviate from norms of rationality in the presence of probability and uncertainty. A look at Laplace's theories and reasoning is striking, both in how modern they seem and in how much progress he made without the benefit of systematic experimentation. We argue that this work points to these theories being more fundamental and less contingent on recent experimental findings than we might have thought. 1. Heuristics and biases, two hundred years ago One sees in this essay that the theory of probabilities is basically only common sense reduced to a calculus. It makes one estimate accurately what right-minded people feel by a sort of instinct, often without being able to give a reason for it. (Laplace, 1825, p. 124)1 A century and a half before the papers of Kahneman and Tversky that kickstarted the \heuris- tics and biases" approach to the psychology of judgment and decision making and the rise of behavioral economics, the celebrated physicist, mathematician, and statistician Pierre-Simon de Laplace wrote a chapter in his Essai Philosophique sur les Probabilit´es that anticipated many of these ideas which have been so influential, from psychology and economics to business and sports.2 ∗We thank Jonathon Baron, Gerd Gigerenzer, Daniel Goldstein, Alex Imas, Daniel Kahneman, and Stephen Stigler for helpful comments and discussions, and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency for partial support of this work through grant D17AC00001. -

UC Merced Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society

UC Merced Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society Title The Representation of Judgment Heuristics and the Generality Problem Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6hv4k2dx Journal Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society, 29(29) ISSN 1069-7977 Author Lee, Carole J. Publication Date 2007 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Representation of Judgment Heuristics and the Generality Problem Carole J. Lee ([email protected]) Department of Philosophy, 50 College Street South Hadley, MA 01033 USA Abstract that are inappropriately characterized and should not be used in the epistemic evaluation of belief. Second, In his debates with Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, Gerd Gigerenzer puts forward a stricter standard for the Gigerenzer’s critiques of Daniel Kahneman and Amos proper representation of judgment heuristics. I argue that Tversky’s judgment heuristics help to recast the generality Gigerenzer’s stricter standard contributes to naturalized problem in naturalized epistemology in constructive ways. epistemology in two ways. First, Gigerenzer’s standard can be In the first part of this paper, I will argue that naturalized used to winnow away cognitive processes that are epistemologists and cognitive psychologists like Gigerenzer inappropriately characterized and should not be used in the have explanatory goals and conundrums in common: in epistemic evaluation of belief. Second, Gigerenzer’s critique helps to recast the generality problem in naturalized particular, both seek to explain the production and epistemic epistemology and cognitive psychology as the methodological status of beliefs by referring to the reliable cognitive problem of identifying criteria for the appropriate processes from which they arise; and both face the specification and characterization of cognitive processes in generality problem in trying to do so. -

Concepts in Bounded Rationality: Perspectives from Reinforcement Learning

Concepts in Bounded Rationality: Perspectives from Reinforcement Learning David Abel Master's Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Philosophy at Brown University Providence, Rhode Island May 2019 This thesis by David Abel is accepted in its present form by the Department of Philosophy as satisfying the thesis requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Date Joshua Schechter, Advisor Approved by the Graduate Council Date Andrew G. Campbell, Dean of the Graduate School i Acknowledgements I am beyond thankful to the many wonderful mentors, friends, colleagues, and family that have supported me along this journey: • A profound thank you to my philosophy advisor, Joshua Schechter { his time, insights, pa- tience, thoughtful questioning, and encouragement have been essential to my own growth and the work reflected in this document. He has been a brilliant mentor to me and I am grateful for the opportunity to learn from him. • I would like to thank my previous philosophy advisors: from highschool, Terry Hansen, John Holloran, and Art Ward, who first gave me the opportunity to explore philosophy and ask big questions; and to my undergraduate mentors, Jason Decker, David Liben-Nowell, and Anna Moltchanova, all of whom helped me grow as a thinker and writer and encouraged me to pursue grad school. • A deep thank you to my recent collaborators, mentors, and colleagues who have contributed greatly to the ideas presented in this work: Cam Allen, Dilip Arumugam, Kavosh Asadi, Owain Evans, Tom Griffiths, Ellis Hershkowitz, Mark Ho, Yuu Jinnai, George Konidaris, Michael Littman, James MacGlashan, Daniel Reichman, Stefanie Tellex, Nate Umbanhowar, and Lawson Wong. -

Behavioral Economics Syllabus

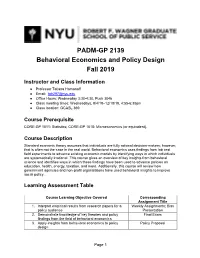

PADM-GP 2139 Behavioral Economics and Policy Design Fall 2019 Instructor and Class Information ● Professor Tatiana Homonoff ● Email: [email protected] ● Office Hours: Wednesday 3:30-4:30, Puck 3046 ● Class meeting times: Wednesdays, 9/4/19–12/18/19, 4:55-6:35pm ● Class location: GCASL 369 Course Prerequisite CORE-GP 1011: Statistics; CORE-GP 1018: Microeconomics (or equivalent). Course Description Standard economic theory assumes that individuals are fully rational decision-makers; however, that is often not the case in the real world. Behavioral economics uses findings from lab and field experiments to advance existing economic models by identifying ways in which individuals are systematically irrational. This course gives an overview of key insights from behavioral science and identifies ways in which these findings have been used to advance policies on education, health, energy, taxation, and more. Additionally, this course will review how government agencies and non-profit organizations have used behavioral insights to improve social policy. Learning Assessment Table Course Learning Objective Covered Corresponding Assignment Title 1. Interpret empirical results from research papers for a Weekly Assignments; Bias policy audience Presentation 2. Demonstrate knowledge of key theories and policy Final Exam findings from the field of behavioral economics 3. Apply insights from behavioral economics to policy Policy Proposal design Page 1 Required Readings Thaler, Richard H., and Cass R. Sunstein. Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Yale University Press, 2008. Excerpts from the following books (provided on NYU Classes): o Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011. Hereafter, referred as TFS. -

Mary L. Steffel

MARY L. STEFFEL D’Amore-McKim School of Business Cell: 646-831-6508 Northeastern University Office: 617-373-4564 202F Hayden Hall, 360 Huntington Avenue [email protected] Boston, MA 02115 www.marysteffel.com EMPLOYMENT AND AFFILIATIONS NORTHEASTERN UNIVERSITY Associate Professor of Marketing, July 2020–present Assistant Professor of Marketing, July 2015–July 2020 Faculty Associate, Center for Health Policy and Healthcare Research, Fall 2015–present Affiliated Faculty, School of Public Policy and Urban Affairs, Fall 2018–present OFFICE OF EVALUATION SCIENCES | GENERAL SERVICES ADMINISTRATION Academic Affiliate, September 2018–present | Fellow, October 2016–September 2018 WHITE HOUSE SOCIAL AND BEHAVIORAL SCIENCES TEAM Fellow, October 2016–January 2017 UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Assistant Professor of Marketing, July 2012–July 2015 EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA Ph.D. Marketing, Postdoctoral Fellowship, August 2012 Dissertation: “Social Comparison in Decisions for Others” Committee: Robyn LeBoeuf, Chris Janiszewski, Lyle Brenner, and John Chambers PRINCETON UNIVERSITY Ph.D. Psychology, June 2009, M.A. Psychology, December 2006 Dissertation: “The Impact of Choice Difficulty on Self and Social Inferences” Committee: Daniel M. Oppenheimer, Eldar Shafir, Daniel Kahneman, Emily Pronin, Deborah Prentice, and Susan Fiske COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY B.A. Psychology (Honors), Summa Cum Laude, May 2004 RESEARCH INTERESTS My research is dedicated to the study of consumer judgment and decision-making. I utilize experiments to examine when consumers call upon others to help them make decisions, how consumers navigate making decisions for others, and how to support consumers in making better decisions. My goal is to broaden the social context in which we understand consumer judgment and decision-making and leverage these insights to address substantive problems in the marketing and policy domains. -

Downloaded/Printed from Heinonline ( Fri Sep 14 16:19:10 2012

Vanderbilt University Law School Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law Vanderbilt Law School Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 2005 The utF ility of Appeal: Disciplinary Insights into the "Affirmance Effect" on the United States Courts of Appeals Chris Guthrie Tracey E. George Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/faculty-publications Part of the Courts Commons, and the Judges Commons Recommended Citation Chris Guthrie and Tracey E. George, The Futility of Appeal: Disciplinary Insights into the "Affirmance Effect" on the United States Courts of Appeals, 32 Florida State University Law Review. 357 (2005) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/faculty-publications/813 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law School Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. +(,121/,1( Citation: 32 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 357 2004-2005 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline (http://heinonline.org) Fri Sep 14 16:19:10 2012 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. THE FUTILITY OF APPEAL: DISCIPLINARY INSIGHTS INTO THE "AFFIRMANCE EFFECT" ON THE UNITED STATES COURTS OF APPEALS CHRIS GUTHRIE* & TRACEY E. GEORGE** I. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 357 II. THE AFFIRMANCE EFFECT ................................................................................... 359 III. THEORETICAL ACCOUNTS OF THE AFFIRMANCE EFFECT .................................... 363 A. Political Science Rational-ActorAccounts .................................................. -

Spudm26 (The 26Th Subjective Probability, Utility, and Decision Making Conference) the Biennial Meeting of the European Association for Decision Making

SPUDM26 (THE 26TH SUBJECTIVE PROBABILITY, UTILITY, AND DECISION MAKING CONFERENCE) THE BIENNIAL MEETING OF THE EUROPEAN ASSOCIATION FOR DECISION MAKING Organizing committee: Shahar Ayal, Interdisciplinary Center (IDC) Herzliya (Chair) Rachel Barkan, Ben Gurion University of the Negev David Budescu, Fordham University Ido Erev, Technion – Israel Institute of Technology Andreas Glöckner, University of Hagen, Germany and Max Planck Institute for Collective Goods, Bonn Guy Hochman, Interdisciplinary Center (IDC) Herzliya llana Ritov, Hebrew University Shaul Shalvi, University of Amsterdam Richárd Szántó, Corvinus University of Budapest Eldad Yechiam – Technion – Israel Institute of Technology SPUDM 26 Conference Master Schedule Sunday - August 20 (Yama, David Elazar 10, Haifa, Near Leonardo Carmel Beach) 16:30 – 18:00 Early registration 18:00 – 19:45 Welcome Reception and Light Dinner 19.45 – 20.00 Greetings 20.00 – 20.30 Maya Bar Hillel, The unbearable lightness of self-induced mind corruption 20.30 – 21.30 Andreas Glöckner, Presidential Address 21.30 –22.00 Desserts Monday - August 21, Industrial Engineering and Management Faculty, Technion 7.45 Bus from Leonardo and 8.00 Bus from Dan Panorama 8:15 - 8.40 Coffee and registration 8:40 - 8:55 Avishai Mandelbaum, Dean of the Faculty of Industrial Engineering and Management, Welcome to the Technion and the big data revolution. 9:00 – 10:30 Paper Session 1 10:30 – 11:00 Coffee Break 11:00 – 12:30 Paper Session 2 12:30 – 14:00 Lunch Break 14:00 – 15:00 Keynote Address 1 – Ido Erev, On anomalies, -

Reasoning the Fast and Frugal Way: Models of Bounded Rationality1

Published in: Psychological Review, 103 (4), 1996, 650–669. www.apa.org/journals/rev/ © 1996 by the American Psychological Association, 0033-295X. Reasoning the Fast and Frugal Way: Models of Bounded Rationality1 Gerd Gigerenzer Max Planck Institute for Psychological Research Daniel G. Goldstein University of Chicago Humans and animals make inferences about the world under limited time and knowledge. In contrast, many models of rational inference treat the mind as a Laplacean Demon, equipped with unlimited time, knowledge, and computational might. Following H. Simon’s notion of satisficing, the authors have pro- posed a family of algorithms based on a simple psychological mechanism: one reason decision making. These fast and frugal algorithms violate fundamental tenets of classical rationality: They neither look up nor integrate all information. By computer simulation, the authors held a competition between the sat- isficing “Take The Best” algorithm and various “rational” inference procedures (e.g., multiple regres- sion). The Take The Best algorithm matched or outperformed all competitors in inferential speed and accuracy. This result is an existence proof that cognitive mechanisms capable of successful performance in the real world do not need to satisfy the classical norms of rational inference. Organisms make inductive inferences. Darwin (1872/1965) observed that people use facial cues, such as eyes that waver and lids that hang low, to infer a person’s guilt. Male toads, roaming through swamps at night, use the pitch of a rival’s croak to infer its size when deciding whether to fight (Krebs & Davies, 1987). Stock brokers must make fast decisions about which of several stocks to trade or invest when only limited information is available. -

Boundedly Rational Borrowing

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2006 Boundedly Rational Borrowing Cass R. Sunstein Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Cass R. Sunstein, "Boundedly Rational Borrowing," 73 University of Chicago Law Review 249 (2006). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Boundedly Rational Borrowing Cass R. Sunsteint Excessive borrowing, no less than insufficient savings, might be a product of bounded ra- tionality. Identifiable psychological mechanisms are likely to contribute to excessive borrowing; these include myopia, procrastination,optimism bias, "miswanting," and what might be called cumulative cost neglect. Suppose that excessive borrowing is a significant problem for some or many; if so, how might the law respond? The first option involves weak paternalism, through debi- asing and other strategies that leave people free to choose as they wish. Another option is strong paternalism, which forecloses choice. Because ofprivate heterogeneity and the risk of government error,regulators should have a firm presumption against strong paternalism,and hence the initial line of defense against excessive borrowing consists of information campaigns, debiasing, and default rules. On imaginable empirical findings, however, there may be a plausible argument for strong paternalismin the form of restrictionson various practices,perhaps including "teaser rates" and late fees The two larger themes applicable in many contexts, involve the importance of an ex post perspective on the consequences of consumer choices and the virtues and limits of weak forms of paternalism,including debiasing and libertarianpaternalism.