Castle Huntly: Its Development and History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter Contents 07-08

Newsletter No 28 Summer/Autumn 2008 He is currently working on a book on the nineteenth- From the Chair century travel photographer Baron Raimund von Stillfried. Welcome to the first of our new shorter-but- hopefully-more-frequent newsletters! The main casualty has been the listings section, which is no New SSAH Grant Scheme longer included. Apologies to those of you who found this useful but it takes absolutely ages to compile and As you’ll know from last issue, we recently launched a the information should all be readily available scheme offering research support grants from £50 to elsewhere. Otherwise you should still find the same £300 to assist with research costs and travel mix of SSAH news and general features – if you have expenses. We’re delighted to say that several any comments on the newsletter or would like to applications have already been received and so far we contribute to future issues, please let us know! have awarded five grants to researchers from around Now, let’s waste no more time and get on the world. Here we present the first two reports with the latest news… from grant recipients on how the money has been Matthew Jarron spent. Committee News Gabriel Montua, Humboldt-Universität Berlin, Germany As promised last issue, we present a profile of our newest committee member: The generous SSAH grant of £206.96 enabled me to cover my travel expanses to the Scottish National Luke Gartlan Gallery of Modern Art in Edinburgh, where I consulted item GMA A42/1/GKA008 from the Luke is a lecturer in the School of Art History at the Gabrielle Keiller Collection: letters exchanged University of St Andrews, where he currently teaches between Salvador Dalí and André Breton. -

Ideas to Inspire

Highland Perthshire and Dundee Follow the River Tay to the sea Dundee City Council © The Atholl Highlanders, Blair Castle Dundee Contemporary Arts Edradour Distillery, near Pitlochry Looking over Dundee and the River Tay from The Law Ideas to inspire Enjoy a wonderful 4-day countryside and city break in the east of Scotland. Within easy reach of Scotland’s central belt, the striking scenery, history and Brilliant events in Perthshire natural heritage of Highland Perthshire is perfectly complemented by the culture, parks, shopping and food and drink of a Dundee city break. May - Atholl Highlanders Parade & Gathering, Blair Castle July - Kenmore Highland Games Starting in the Pitlochry area, explore the history of elegant Blair Castle, then head for Loch Tummel and admire the wonderful Queen’s View with its July - GWCT Scottish Game Fair, Scone Palace, by Perth delightful Forestry Commission Scotland visitor centre. Neolithic history is the August - Aberfeldy Show & Games next stop as you marvel at the reconstructed Iron Age crannog at the Scottish August - Blair Castle International Horse Trials & Country Fair, Blair Atholl Crannog Centre. End the day with a visit to Dewar’s World of Whisky, where a October - Perthshire Amber Music Festival, various Perthshire venues tour of Aberfeldy Distillery blends perfectly with displays showcasing how Dewar’s has become one of the world’s favourite whiskies. October - The Enchanted Forest, Pitlochry Find out about these and other events at www.visitscotland.com/perthshire Day two begins with a stroll through the woodlands of The Hermitage near Dunkeld, towards the impressive Black Linn waterfall. Next, stop off at Stanley Mills and discover Perthshire’s fascinating industrial heritage, before heading to Perth to explore the absorbing Black Watch Museum. -

Asva Visitor Trend Report - September 2009/2010

ASVA VISITOR TREND REPORT - SEPTEMBER 2009/2010 OVERVIEW Visitor numbers for September 2009/2010 were received from 218 sites. 9 sites requested confidentiality, and although their numbers have been included in the calculations, they do not appear in the tables below. There are 14 sites for which there is no directly comparable data for 2009. The 2010 figures do appear in the table below for information but were not included in the calculations. Thus, directly comparable data has been used from 204 sites. From the usable data from 204 sites, the total number of visits recorded in September 2010 was 1,551,800 this compares with 1,513,324 in 2009 and indicates an increase of 2.5% for the month. Weatherwise, September was a changeable month with rain and strong winds, with average rainfall up to 150% higher than average Some areas experienced localised flooding and there was some disruption to ferry and rail services. The last weekend of the month saw clear skies in a northerly wind which brought local air frosts to some areas and a few places saw their lowest temperatures in September in 20 to30 years. http://news.bbc.co.uk/weather/hi/uk_reviews/default.stm September 2009 September 2010 % change SE AREA (156) 1,319,250 1,356,219 2.8% HIE AREA (48) 194,074 195,581 0.8% SCOTLAND TOTAL (204) 1,513,324 1,551,800 2.5% Table 1 – Scotland September 2009/2010 SE AREA In September 2010 there were 1,356,219 visits recorded, compared to 1,319,250 during the same period in 2009, an increase of 2.8%. -

Asset Management Plan for the Properties in the Care of Scottish Ministers 2018 Contents

ASSET MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR THE PROPERTIES IN THE CARE OF SCOTTISH MINISTERS 2018 CONTENTS Introduction ..................................................3 5.0 Meeting conservation challenges ... 25 1.0 Cultural Heritage Asset 6.0 Ensuring high standards and Management – challenges, continuity of care ..................................... 26 opportunities and influences ................... 4 1.1 Objectives of the AMP ������������������������������������� 5 7.0 Standards and assurance .................27 1.2 Adding value through asset 7.1 Compliance .........................................................27 management ........................................................ 7 7.2 Compliance management 1.3 Scotland’s changing climate ......................... 9 roles and responsibilities for physical assets ............................................27 2.0 The Properties in Care ...................... 10 7.3 Visitor safety management ..........................27 7.4 Conservation principles and standards ...28 2.1 Asset Schedule ................................................. 10 7.5 Project management and regulatory 2.2 The basis of state care ................................... 10 consents ............................................................. 30 2.3 Overview of the properties in care ..................11 7.6 External peer review ...................................... 30 2.4 Statements of cultural significance .............11 2.5 Acquisitions and disposal ..............................12 8.0 Delivering our climate change objectives -

Post Office Perth Directory

3- -6 3* ^ 3- ^<<;i'-X;"v>P ^ 3- - « ^ ^ 3- ^ ^ 3- ^ 3* -6 3* ^ I PERTHSHIRE COLLECTION 1 3- -e 3- -i 3- including I 3* ^ I KINROSS-SHIRE | 3» ^ 3- ^ I These books form part of a local collection | 3. permanently available in the Perthshire % 3' Room. They are not available for home ^ 3* •6 3* reading. In some cases extra copies are •& f available in the lending stock of the •& 3* •& I Perth and Kinross District Libraries. | 3- •* 3- ^ 3^ •* 3- -g Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/postofficeperthd1878prin THE POST OFFICE PERTH DIRECTORY FOR 1878 AND OTHER USEFUL INFORMATION. COMPILED AND ARRANGED BY JAMES MARSHALL, POST OFFICE. WITH ^ Jleto ^lan of the Citg ant) i^nbixons, ENGRAVED EXPRESSLY FOR THE WORK. PERTH: PRINTED FOR THE PUBLISHER BY LEITCH & LESLIE. PRICE THREE SHILLINGS. I §ooksz\ltmrW'Xmm-MBy & Stationers, | ^D, SILVER, COLOUR, & HERALDIC STAMPERS, Ko. 23 Qeorqe $treet, Pepjh. An extensive Stock of BOOKS IN GENERAL LITERATURE ALWAYS KEPT IN STOCK, THE LIBRARY receives special attention, and. the Works of interest in History, Religion, Travels, Biography, and Fiction, are freely circulated. STATIONEEY of the best Englisli Mannfactura.. "We would direct particular notice to the ENGRAVING, DIE -SINKING, &c., Which are carried on within the Previises. A Large and Choice Selection of BKITISK and FOEEIGU TAEOT GOODS always on hand. gesigns 0f JEonogntm^, Ac, free nf rhitrge. ENGLISH AND FOREIGN NE^A^SPAPERS AND MAGAZINES SUPPLIED REGULARLY TO ORDER. 23 GEORGE STREET, PERTH. ... ... CONTENTS. Pag-e 1. -

The High School of Dundee Surnames City Archives Starting by K

Friends of Dundee The High School of Dundee Surnames City Archives starting by K Selected Admission Records - Boys 1880 to 1904 Surname Prename Age DoB Birthplace Father Father's Occupation Address Year PrevSchool Kane Paul E. 12 Dundee Paul Merchant 23, Union Street 1880 Tay St. Acad. Keay Andrew 13 Dundee Alexander Clerk 193, Blackness Road 1883 Hawkhill Public School Keay William F. 15 26/03/1990 Dundee Thomas C. Engineer Clifton Bank, Dalkeith 1904 None Road Keay William F. 15 26/03/1990 Dundee Thomas C. Engineer Clifton Bank, Dalkeith 1904 None Road Keay William F. 7 Dundee T.C. Mill furnisher Clifton Bank, Dalkeith 1897 Road Keay Cuthbert M. 13 London William A. Engineer Camphill, Broughty Ferry 1897 Grove Academy Keill Patrick 9 Invergowrie William Farmer Mylnefield, Invergowrie 1883 Home Keiller Frederick 11 Dundee George Merchant Templehall, Longforgan 1880 Miss Buchan's Keiller Alexander 14 Dundee George C. Jute merchant Templehall, Longforgan 1889 Miss Buchan Keiller Archie 13 Dundee George C. Jute merchant Templehall, Longforgan 1889 Miss Buchan Keiller George W. 13 Longforgan George c. Merchant Hawkhill House 1897 Miss Brough Keiller William 12 Dundee George Merchant Templehall, Longforgan 1880 Miss Buchan's Keiller Frederick 14 Dundee George C. Fire agent Temple hall House, 1883 Miss Buchan George Longforgan Keiller William Lockart 15 Dundee George C. Fire agent Temple Hall House, 1883 Miss Buchan Longforgan 04 June 2011 Page 1 of 5 Surname Prename Age DoB Birthplace Father Father's Occupation Address Year PrevSchool Keiller Patrick 17 Longforgan George C. Merchant Hawkhill House 1897 Mr. Irvine's Keith Harry M. -

Enjoy 48 Hours in Dundee

Enjoy 48 Hours in Dundee www.dundee.com Welcome to Dundee, one of Scotland’s most dynamic cities, where you are guaranteed a warm Scottish welcome, many places to eat and drink, great attractions and, because of Dundee’s proximity to Fife, Angus and Perthshire, some breathtaking scenery. The city benefits from a central geographic location, and has an excellent road, rail and air network with daily flights to London Stansted. www.dundee.com/visit There is so much on offer - V&A Dundee opened in 2018 – It is the first ever dedicated design museum in Scotland and the only other V&A Museum anywhere in the world outside London. Among a host of other things Dundee proudly celebrates its seafaring heritage. RRS Discovery, which was built in the city, is the vessel sailed by Captain Robert Falcon Scott on his first voyage to Antarctica in 1901. Whilst at City Quay you will discover one of the oldest British built wooden frigates still afloat, HMS Unicorn. Visit the award winning textile heritage centre, Verdant Works including the refurbished High Mill or The McManus: Dundee’s Art Gallery and Museum, home to one of Scotland’s most impressive collections of fine and decorative art. Visit Dundee’s Museum of Transport and explore the city’s West End, where the Dundee Repertory Theatre offers a wide range of genres and Dundee Contemporary Arts (DCA) housing two cinemas and contemporary art exhibitions. Behind the DCA you will find Dundee Science Centre. Enjoy discovering Dundee city centre where the Overgate is the jewel in Dundee’s retail crown. -

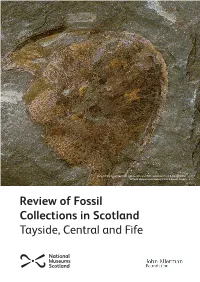

Tayside, Central and Fife Tayside, Central and Fife

Detail of the Lower Devonian jawless, armoured fish Cephalaspis from Balruddery Den. © Perth Museum & Art Gallery, Perth & Kinross Council Review of Fossil Collections in Scotland Tayside, Central and Fife Tayside, Central and Fife Stirling Smith Art Gallery and Museum Perth Museum and Art Gallery (Culture Perth and Kinross) The McManus: Dundee’s Art Gallery and Museum (Leisure and Culture Dundee) Broughty Castle (Leisure and Culture Dundee) D’Arcy Thompson Zoology Museum and University Herbarium (University of Dundee Museum Collections) Montrose Museum (Angus Alive) Museums of the University of St Andrews Fife Collections Centre (Fife Cultural Trust) St Andrews Museum (Fife Cultural Trust) Kirkcaldy Galleries (Fife Cultural Trust) Falkirk Collections Centre (Falkirk Community Trust) 1 Stirling Smith Art Gallery and Museum Collection type: Independent Accreditation: 2016 Dumbarton Road, Stirling, FK8 2KR Contact: [email protected] Location of collections The Smith Art Gallery and Museum, formerly known as the Smith Institute, was established at the bequest of artist Thomas Stuart Smith (1815-1869) on land supplied by the Burgh of Stirling. The Institute opened in 1874. Fossils are housed onsite in one of several storerooms. Size of collections 700 fossils. Onsite records The CMS has recently been updated to Adlib (Axiel Collection); all fossils have a basic entry with additional details on MDA cards. Collection highlights 1. Fossils linked to Robert Kidston (1852-1924). 2. Silurian graptolite fossils linked to Professor Henry Alleyne Nicholson (1844-1899). 3. Dura Den fossils linked to Reverend John Anderson (1796-1864). Published information Traquair, R.H. (1900). XXXII.—Report on Fossil Fishes collected by the Geological Survey of Scotland in the Silurian Rocks of the South of Scotland. -

Post Office Perth Directory

f\ &rf-.,.-. •e •e •e -6 •6 •6 •6 •6 •8 •e •6 •6 •6 * •6 s -5 8 -6 PERTHSHIRE COLLECTION •e •g •B -6 including •6 -5 •6 KINROSS-SHIRE -6 •g •6 •6 •6 These books form part of a local collection •6 •g permanently available in the Perthshire •g •6 Room. They are not available for home •e •e reading. In some cases extra copies are •g •e available in the lending stock of the •6 •g Perth and Kinross District Libraries •6 •6 -6 •g Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/postofficeperthd1874prin ANDREW BROWN, (Successor to E. H. Grasby), 23 HIGH STREET, PERTH, MANUFACTURER OF HOSIERY AND UNDERCLOTHING Of all descriptions, in Silk, Cotton, Merino, and Lambs' Wool, warranted not to shrink. LADIES', GENTLEMEN'S, AND CHILDREN'S DRAWERS, VESTS, AND DRESSES, In Silk, Cotton, Merino, and Lambs' Wool, Ribbed or Plain. LADIES'^ GENTLEMEN'^ AND CHILDREN'S HOSIERY, In Cotton, Lace Cotton, Thread, Lace Thread, Balbriggan, Merino, Lambs' Wool, and Silk. TARTAN HOSE IN GREAT VARIETY. DRESS SHIRTS & COLOURED FLANNEL SHIRTS. Scarfs, Ties, Collars, Gloves. Every description of Hosiery and Underclothing made to order. 1 < E— H GO WPS UJ > Q_ go o UJ 00 LU PS w DC ,— —1 H CO afe o f >— a $ w o 00 w 5^ LU 5s E— 3 go O O THE POST OFFICE PERTH DIRECTORY FOR 1874, AND OTHER USEFUL INFORMATION. COMPILED AND ARRANGED BY JAMES MARSHALL, POST OFFICE. WITH Jl Jlsto fllan xrf the QLxty. -

Historic Environment Scotland Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC013 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90043) Taken into State care: 1973 (Ownership) Last reviewed: 2017 HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE BROUGHTY CASTLE We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE BROUGHTY CASTLE CONTENTS 1 Summary 2 1.1 Introduction 2 1.2 Statement of significance 2 2 Assessment of values 3 2.1 Background 3 2.2 Evidential values 6 2.3 Historical values 7 2.4 Architectural and artistic values 9 2.5 Landscape and aesthetic values 12 2.6 Natural heritage values 13 2.7 Contemporary/use values 13 3 Major gaps in understanding 14 4 Associated properties 15 5 Keywords 15 Bibliography 15 APPENDICES Appendix 1: Timeline 16 Appendix 2: A contribution on the 19th- and 20th-century 22 defences of Broughty Castle Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH 1 1 Summary 1.1 Introduction Broughty Castle is an imposing stronghold situated on a promontory at the mouth of the Tay estuary, unusually combining elements of medieval and Victorian military architecture. Its history reflects several turbulent episodes in Scotland’s last 500 years of history, and encapsulates the story of the defence of the Tay estuary. -

Which Is Scotland's Artists' Town?

The North*s Original Free Arts Newspaper + www.artwork.co.uk Number 192 Pick up your own FREE copy and find out what’s really happening in the arts March/April 2016 Self Portrait, George Dutch Davidson, 1898. From Art in Dundee 1867-1924, by Matthew Jarron, reviewed in this issue. Image © Dundee City Council. Inside: Which is Scotland’s Artists’ Town? A Home from Home for Artists in London artWORK 192 March/April 2016 Page 2 artWORK 192 March/April 2016 Page 2 SPECIAL OFFER - ANY 3 BOOKS SENT POST FREE (UK ONLY) FOR £20.00 (TICK BELOW) GAZETTEER OF SCOTLAND – How high that mountain? How deep that loch? Reprint of the ’37 edn. 07179 460 88 £9.99 ____ GEOFF: The Life of Geoffrey M. Shaw – Strathclyde’s charismatic leader, profiled by Ron Ferguson 0905489 00 4 £9.99 ____ GEORGE WYLLIE: MY WORDS – George Wyllie’s quirky Essays for ArtWork - illustrated by George 0905489 56 X £4.95 ____ The New Borders Railway Souvenir Map has proved a runaway success. It joins a stable of popular HIGHLAND STEAM: A Scrapbook of Images from the Kyle, Mallaig and Highland lines – Large Famedram rail maps, some of which have sold hundreds of thousands of copies. To order a single copy, format paperback, with 160 pages of glorious colour pictures of steam in a Highland setting 978 0905489 90 2 £9.99 ____ sent First Class Post, send £3.50; two copies: £5.00; Special Offer: 3 Different Rail Maps (Borders, Mallaig and Kyle maps) sent first class mail: £5.00. -

Dundee City Council Report To: Policy and Resources Committee– 22 April 2019 Report On: Accredited Museums Collections

DUNDEE CITY COUNCIL REPORT TO: POLICY AND RESOURCES COMMITTEE– 22 APRIL 2019 REPORT ON: ACCREDITED MUSEUMS COLLECTIONS DEVELOPMENT POLICY REPORT BY: DIRECTOR, LEISURE AND CULTURE REPORT NO: 105-2019 1.0 PURPOSE OF REPORT 1.1 To seek approval for the Collections Development Policy 2019 – 2024 for Dundee City’s collections which are managed, maintained and developed by the Cultural Services Section of Leisure & Culture Dundee. 2.0 RECOMMENDATIONS 2.1 It is recommended that the Committee approve this Policy 3.0 FINANCIAL IMPLICATIONS 3.1 There are no direct financial implications for Leisure & Culture Dundee or Dundee City Council Revenue Budgets arising from this report. 4.0 BACKGROUND 4.1 Agreement of this Policy will allow Leisure & Culture Dundee to strengthen the permanent collection and fulfil the terms of the Accreditation Scheme for Museums in the UK for 2019 to 2024. 4.2 This Policy was agreed by the Leisure & Culture Dundee Board on 5 December 2018. 5.0 POLICY IMPLICATIONS 5.1 This report has been subject to an assessment of any impacts on Equality and Diversity, Fairness and Poverty, Environment and Corporate Risk. There are no major issues. 6.0 CONSULTATION 6.1 The Senior Management Team and Board of Leisure & Culture Dundee, Museums Galleries Scotland, and the Dundee City Council Management Team have been consulted in the preparation of this report and are in agreement with its contents. 7.0 BACKGROUND PAPERS 7.1 None. Stewart Murdoch Director, Leisure and Culture March 2019 1 LEISURE & CULTURE DUNDEE – COLLECTIONS DEVELOPMENT POLICY 2019 – 2024 Name of museum: All museums managed by Leisure & Culture Dundee and not limited to The McManus, Mills Observatory and Broughty Castle Museums.