Kirkton of Glen Isla to Alyth Place Names of the Cateran Trail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Post Office Perth Directory

i y^ ^'^•\Hl,(a m \Wi\ GOLD AND SILVER SMITH, 31 SIIG-S: STI^EET. PERTH. SILVER TEA AND COFFEE SERVICES, BEST SHEFFIELD AND BIRMINGHAM (!^lettro-P:a3tteto piateb Crutt mb spirit /tamtjs, ^EEAD BASKETS, WAITEKS, ^NS, FORKS, FISH CARVERS, ci &c. &c. &c. ^cotct) pearl, pebble, arib (STatntgorm leroeller^. HAIR BRACELETS, RINGS, BROOCHES, CHAINS, &c. PLAITED AND MOUNTED. OLD PLATED GOODS RE-FINISHED, EQUAL TO NEW. Silver Plate, Jewellery, and Watches Repaired. (Late A. Cheistie & Son), 23 ia:zc3-i3: sti^eet^ PERTH, MANUFACTURER OF HOSIERY Of all descriptions, in Cotton, Worsted, Lambs' Wool, Merino, and Silk, or made to Order. LADIES' AND GENTLEMEN'S ^ilk, Cotton, anb SEoollen ^\}xxi^ attb ^Mktt^, LADIES' AND GENTLEMEN'S DRAWERS, In Silk, Cotton, Worsted, Merino, and Lambs' Wool, either Kibbed or Plain. Of either Silk, Cotton, or Woollen, with Plain or Ribbed Bodies] ALSO, BELTS AND KNEE-CAPS. TARTAN HOSE OF EVERY VARIETY, Or made to Order. GLOVES AND MITTS, In Silk, Cotton, or Thread, in great Variety and Colour. FLANNEL SHOOTING JACKETS. ® €^9 CONFECTIONER AND e « 41, GEORGE STREET, COOKS FOR ALL KINDS OP ALSO ON HAND, ALL KINDS OF CAKES AND FANCY BISCUIT, j^jsru ICES PTO*a0^ ^^te mmU to ©vto- GINGER BEER, LEMONADE, AND SODA WATER. '*»- : THE POST-OFFICE PERTH DIRECTOEI FOR WITH A COPIOUS APPENDIX, CONTAINING A COMPLETE POST-OFFICE DIRECTORY, AND OTHER USEFUL INFORMATION. COMPILED AND ARRANGED BY JAMES MAESHALL, POST-OFFICE. WITH ^ pUtt of tl)e OTtts atiti d^nmxonn, ENGEAVED EXPRESSLY FOB THE WORK. PEETH PRINTED FOR THE PUBLISHER BY C. G. SIDEY, POST-OFFICE. -

Perth & Kinross Council Archive

Perth & Kinross Council Archive Collections Business and Industry MS5 PD Malloch, Perth, 1883-1937 Accounting records, including cash books, balance sheets and invoices,1897- 1937; records concerning fishings, managed or owned by PD Malloch in Perthshire, including agreements, plans, 1902-1930; items relating to the maintenance and management of the estate of Bertha, 1902-1912; letters to PD Malloch relating to various aspects of business including the Perthshire Fishing Club, 1883-1910; business correspondence, 1902-1930 MS6 David Gorrie & Son, boilermakers and coppersmiths, Perth, 1894-1955 Catalogues, instruction manuals and advertising material for David Gorrie and other related firms, 1903-1954; correspondence, specifications, estimates and related materials concerning work carried out by the firm, 1893-1954; accounting vouchers, 1914-1952; photographic prints and glass plate negatives showing machinery and plant made by David Gorrie & Son including some interiors of laundries, late 19th to mid 20th century; plans and engineering drawings relating to equipment to be installed by the firm, 1892- 1928 MS7 William and William Wilson, merchants, Perth and Methven, 1754-1785 Bills, accounts, letters, agreements and other legal papers concerning the affairs of William Wilson, senior and William Wilson, junior MS8 Perth Theatre, 1900-1990 Records of Perth Theatre before the ownership of Marjorie Dence, includes scrapbooks and a few posters and programmes. Records from 1935 onwards include administrative and production records including -

Bridge of Earn Community Council

Earn Community Conversation – Final Report 1.1 Bridge of Earn Community Council - Community Conversation January 2020 Prepared by: Sandra Macaskill, CaskieCo T 07986 163002 E [email protected] 1 Earn Community Conversation – Final Report 1.1 Executive Summary – Key Priorities and Possible Actions The table below summaries the key actions which people would like to see as a result of the first Earn Community Conversation. Lead players and possible actions have also been suggested but are purely at the discretion of Earn Community Council. Action Lead players First steps/ Quick wins A new doctor’s surgery/ healthcare facility • Community • Bring key players together to plan an innovative for Bridge of Earn e.g. minor ailments, • NHS fit for the future GP and health care provision district nurse for Bridge of Earn • Involve the community in designing and possibly delivering the solution Sharing news and information – • Community Council • seeking funding to provide a local bi-monthly Quick • Newsletter in paper form • community newsletter Win • Notice boards at Wicks of Baigle • develop a Community Council or community Rd website where people can get information and • Ways of creating inclusive possibly have a two-way dialogue (continue conversations conversation) • enable further consultation on specific topics No public toilet facilities in Main Street • local businesses • Is there a comfort scheme in operation which Bridge of Earn • PKC could be extended? Public Transport • Community • Consult local people on most needed routes Bus services -

Sol-Y-Mar Forgandenny Road Bridge of Earn Sol-Y-Mar | Forgandenny Road, Bridge of Earn

SOL-Y-MAR FORGANDENNY ROAD BRIDGE OF EARN SOL-Y-MAR | FORGANDENNY ROAD, BRIDGE OF EARN Boasting exceptionally generous accommodation and stunning country views. This deceptively spacious 5/6 bedroom 3 public room detached villa benefits from oil-fired central heating, double glazing, excellent storage space, considerable off-street parking, a large garage and private garden grounds extending to around 1/3 of an acre in total and enjoying a sunny south-facing aspect. Having undergone a major extension and renovation in recent years, the property has been transformed to create a light and modern home, complimented by some superb eye-catching features. See this property in more detail on YouTube https://www.youtube.com/embed/lKLj9ejXUM0 Buying your new home the Clyde Property way... 1. Go to the App Store or Google Play 2. Tap on the AR logo. 3. Point your device camera over the The lounge with sliding doors opening and search for CLYDE PROPERTY and image on the brochure front cover or out onto the decking download our new App. any image showing the AR logo. See the image come to life in full HD with our brand new Augmented Reality App. www.clydeproperty.co.uk The dining kitchen. Alternative views of the kitchen and seating area. Ground floor: The property is entered by a bright hallway with storage cupboard, doors to various rooms and stairs to the upper level. There is also an additional entry point into the property which leads into the utility area which has space for plumbing for appliances. The fantastic kitchen dining area is fitted with a shaker style range of base and wall units with granite worktops and a centre island with a solid teak work surface, an AGA and integrated appliances. -

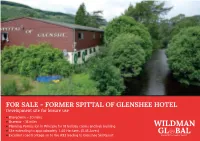

Wildman Global Limited for Themselves and for the Vendor(S) Or Lessor(S) of This Property Whose Agents They Are, Give Notice That: 1

FOR SALE - FORMER SPITTAL OF GLENSHEE HOTEL Development site for leisure use ◆ Blairgowrie – 20 miles ◆ Braemar – 15 miles ◆ Planning Permission in Principle for 18 holiday cabins and hub building WILDMAN ◆ Site extending to approximately 1.40 Hectares (3.45 Acres) GL BAL ◆ Excellent road frontage on to the A93 leading to Glenshee Ski Resort PROPERTY CONSULTANT S LOCATION ACCOMMODATION VIEWING The Spittal of Glenshee lies at the head of Glenshee in the The subjects extend to an approximate area of 1.40 Hectares Strictly by appointment with the sole selling agents. highlands of eastern Perth and Kinross, Scotland. The village has (3.45 Acres). The site plan below illustrates the approximate become a centre for travel, tourism and winter sports in the region. site boundary. SITE CLEARANCE The subjects are directly located off the A93 Trunk Road which The remaining buildings and debris will be removed from the site by leads from Blairgowrie north past the Spittal to the Glenshee Ski PLANNING the date of entry. Centre and on to Braemar. The subjects are sold with the benefit of Planning Permission in Principle (PPiP) from Perth & Kinross Council to develop the entire SERVICES The village also provides a stopping place on the Cateran Trail site to provide 18 holiday cabins, a hub building and associated car ◆ Mains electricity waymarked long distance footpath which provides a 64-mile (103 parking. ◆ Mains water km) circuit in the glens of Perthshire and Angus. ◆ Further information with regard to the planning consent is available Private drainage DESCRIPTION to view on the Perth & Kinross website. -

Notices and Proceedings

THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER FOR THE SCOTTISH TRAFFIC AREA NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 2005 PUBLICATION DATE: 15 April 2013 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 06 May 2013 Correspondence should be addressed to: Scottish Traffic Area Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Fax: 0113 249 8142 Website: www.gov.uk The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Notices and Proceedings will be published on: 29/04/2013 Publication Price £3.50 (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS Important Information All correspondence relating to bus registrations and public inquiries should be sent to: Scottish Traffic Area Level 6 The Stamp Office 10 Waterloo Place Edinburgh EH1 3EG The public counter in Edinburgh is open for the receipt of documents between 9.30am and 4pm Monday to Friday. Please note that only payments for bus registration applications can be made at this counter. The telephone number for bus registration enquiries is 0131 200 4927. General Notes Layout and presentation – Entries in each section (other than in section 5) are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry is prefaced by a reference number, which should be quoted in all correspondence or enquiries. Further notes precede sections where appropriate. Accuracy of publication – Details published of applications and requests reflect information provided by applicants. -

Clan Macthomas Society

Clan MacTHOMAS Society Modern Ancient CREST: A demi-cat-a-mountain rampant guardant Proper, grasping in his dexter paw a serpent Vert, langued Gules, its tail environing the sinister paw MOTTO: Deo Juvante Invidiam Superabo, With God's help I will overcome envy SEPTS: Combie, MacOmie, MacOmish, McColm, McComas, McComb, McCombe, McCombie, McComie, McComish, Tam, Thom, Thomas, Thoms, Thomson A Short History: Thomas, a Gaelic speaking Highlander, known as Tomaidh Mor ('Great Tommy'), was a descendant of the Clan Chattan Mackintoshes, Thomas lived in the 15th century, at a time when the Clan Chattan Confederation had become large and unmanageable and so he took his kinsmen and followers across the Grampians, from Badenoch to Glenshee where they settled and flourished, being known as McComie (phonetic form of the Gaelic MacThomaidh), McColm and McComas (from MacThom and MacThomas). To the Government in Edinburgh, they were known as MacThomas and are so described in the Roll of the Clans in the Acts of the Scottish Parliament of 1587 and 1595 and MacThomas remains the official name of the Clan to this day. The early chiefs of the Clan MacThomas were seated at the Thom, on the east bank of the Shee Water opposite the Spittal of Glenshee. In about 1600, when the 4th Chief, Robert MacThomaidh of the Thom was murdered, the chiefship passed to his brother, John McComie of Finegand, about three miles down the Glen, which became the seat of the chiefs. By now, the MacThomases had acquired a lot of property in the glen and houses were well established at Kerrow and Benzian with shielings up Glen Beag. -

10 Culteuchar Bank Ardargie Forgandenny PH2 9QR

To view the HD video click here 10 Culteuchar Bank Ardargie Forgandenny PH2 9QR clydeproperty.co.uk | page 1 clydeproperty.co.uk clydeproperty.co.uk | page 2 clydeproperty.co.uk | page 3 A beautifully presented five bedroom detached villa, positioned in a prime plot position in a secluded corner of an exclusive development within the popular hamlet of Ardargie. Built in 1998 this exceptional family home has accommodation formed over two floor levels and comprises; welcoming reception hallway, rear facing sitting room with adjacent dining room, fully fitted dining kitchen providing access to a lovely bright sun room and useful utility room. There are two bedrooms on the ground floor, one is currently being used as a home office and the other features a en suite shower room. A cloakroom WC completes the ground level accommodation. Stairs from the hallway lead to a spacious landing and three further At a glance double bedrooms and a well appointed family bathroom. Warmth Detached villa is provided through gas central heating and windows are double Five bedrooms glazed throughout. Fully fitted dining kitchen Lovely bright sun room Sitting room Cloakroom WC Private gardens The finer detail Prime plot position Gas central heating Double glazed windows Utility room Detached double garage EPC Band E clydeproperty.co.uk | page 5 clydeproperty.co.uk | page 6 clydeproperty.co.uk | page 7 clydeproperty.co.uk | page 8 One of the main features of the property is the generous and beautifully a further 2.5 miles to the east. In addition, there is another primary school maintained, private gardens. -

The Dalradian Rocks of the North-East Grampian Highlands of Scotland

Revised Manuscript 8/7/12 Click here to view linked References 1 2 3 4 5 The Dalradian rocks of the north-east Grampian 6 7 Highlands of Scotland 8 9 D. Stephenson, J.R. Mendum, D.J. Fettes, C.G. Smith, D. Gould, 10 11 P.W.G. Tanner and R.A. Smith 12 13 * David Stephenson British Geological Survey, Murchison House, 14 West Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3LA. 15 [email protected] 16 0131 650 0323 17 John R. Mendum British Geological Survey, Murchison House, West 18 Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3LA. 19 Douglas J. Fettes British Geological Survey, Murchison House, West 20 Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3LA. 21 C. Graham Smith Border Geo-Science, 1 Caplaw Way, Penicuik, 22 Midlothian EH26 9JE; formerly British Geological Survey, Edinburgh. 23 David Gould formerly British Geological Survey, Edinburgh. 24 P.W. Geoff Tanner Department of Geographical and Earth Sciences, 25 University of Glasgow, Gregory Building, Lilybank Gardens, Glasgow 26 27 G12 8QQ. 28 Richard A. Smith formerly British Geological Survey, Edinburgh. 29 30 * Corresponding author 31 32 Keywords: 33 Geological Conservation Review 34 North-east Grampian Highlands 35 Dalradian Supergroup 36 Lithostratigraphy 37 Structural geology 38 Metamorphism 39 40 41 ABSTRACT 42 43 The North-east Grampian Highlands, as described here, are bounded 44 to the north-west by the Grampian Group outcrop of the Northern 45 Grampian Highlands and to the south by the Southern Highland Group 46 outcrop in the Highland Border region. The Dalradian succession 47 therefore encompasses the whole of the Appin and Argyll groups, but 48 also includes an extensive outlier of Southern Highland Group 49 strata in the north of the region. -

Post Office Perth Directory

3- -6 3* ^ 3- ^<<;i'-X;"v>P ^ 3- - « ^ ^ 3- ^ ^ 3- ^ 3* -6 3* ^ I PERTHSHIRE COLLECTION 1 3- -e 3- -i 3- including I 3* ^ I KINROSS-SHIRE | 3» ^ 3- ^ I These books form part of a local collection | 3. permanently available in the Perthshire % 3' Room. They are not available for home ^ 3* •6 3* reading. In some cases extra copies are •& f available in the lending stock of the •& 3* •& I Perth and Kinross District Libraries. | 3- •* 3- ^ 3^ •* 3- -g Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/postofficeperthd1878prin THE POST OFFICE PERTH DIRECTORY FOR 1878 AND OTHER USEFUL INFORMATION. COMPILED AND ARRANGED BY JAMES MARSHALL, POST OFFICE. WITH ^ Jleto ^lan of the Citg ant) i^nbixons, ENGRAVED EXPRESSLY FOR THE WORK. PERTH: PRINTED FOR THE PUBLISHER BY LEITCH & LESLIE. PRICE THREE SHILLINGS. I §ooksz\ltmrW'Xmm-MBy & Stationers, | ^D, SILVER, COLOUR, & HERALDIC STAMPERS, Ko. 23 Qeorqe $treet, Pepjh. An extensive Stock of BOOKS IN GENERAL LITERATURE ALWAYS KEPT IN STOCK, THE LIBRARY receives special attention, and. the Works of interest in History, Religion, Travels, Biography, and Fiction, are freely circulated. STATIONEEY of the best Englisli Mannfactura.. "We would direct particular notice to the ENGRAVING, DIE -SINKING, &c., Which are carried on within the Previises. A Large and Choice Selection of BKITISK and FOEEIGU TAEOT GOODS always on hand. gesigns 0f JEonogntm^, Ac, free nf rhitrge. ENGLISH AND FOREIGN NE^A^SPAPERS AND MAGAZINES SUPPLIED REGULARLY TO ORDER. 23 GEORGE STREET, PERTH. ... ... CONTENTS. Pag-e 1. -

The High School of Dundee Surnames City Archives Starting by K

Friends of Dundee The High School of Dundee Surnames City Archives starting by K Selected Admission Records - Boys 1880 to 1904 Surname Prename Age DoB Birthplace Father Father's Occupation Address Year PrevSchool Kane Paul E. 12 Dundee Paul Merchant 23, Union Street 1880 Tay St. Acad. Keay Andrew 13 Dundee Alexander Clerk 193, Blackness Road 1883 Hawkhill Public School Keay William F. 15 26/03/1990 Dundee Thomas C. Engineer Clifton Bank, Dalkeith 1904 None Road Keay William F. 15 26/03/1990 Dundee Thomas C. Engineer Clifton Bank, Dalkeith 1904 None Road Keay William F. 7 Dundee T.C. Mill furnisher Clifton Bank, Dalkeith 1897 Road Keay Cuthbert M. 13 London William A. Engineer Camphill, Broughty Ferry 1897 Grove Academy Keill Patrick 9 Invergowrie William Farmer Mylnefield, Invergowrie 1883 Home Keiller Frederick 11 Dundee George Merchant Templehall, Longforgan 1880 Miss Buchan's Keiller Alexander 14 Dundee George C. Jute merchant Templehall, Longforgan 1889 Miss Buchan Keiller Archie 13 Dundee George C. Jute merchant Templehall, Longforgan 1889 Miss Buchan Keiller George W. 13 Longforgan George c. Merchant Hawkhill House 1897 Miss Brough Keiller William 12 Dundee George Merchant Templehall, Longforgan 1880 Miss Buchan's Keiller Frederick 14 Dundee George C. Fire agent Temple hall House, 1883 Miss Buchan George Longforgan Keiller William Lockart 15 Dundee George C. Fire agent Temple Hall House, 1883 Miss Buchan Longforgan 04 June 2011 Page 1 of 5 Surname Prename Age DoB Birthplace Father Father's Occupation Address Year PrevSchool Keiller Patrick 17 Longforgan George C. Merchant Hawkhill House 1897 Mr. Irvine's Keith Harry M. -

Quiech Mill Alyth PH11 8JR

Quiech Mill Alyth PH11 8JR Attractive detached farmhouse set in a private location in rural Perthshire • 4 Bedrooms • Open plan sitting room/kitchen • Double Glazing • Landlord Registration number: 209672/340/18150 • EPC Rating: E £995 pcm, unfurnished Savills Perth 55 York Place Perth Scotland PH2 8EH Sue Murray [email protected] 01738 477532 savills.co.uk Page 1 of 3 Quiech Mill Alyth PH11 8JR Page 2 of 3 Quiech Mill Alyth PH11 8JR Location Quiech Mill is set in a private location, but remains accessible with good road links to Perth and Dundee. Mainline rail services are also located in Perth and Dundee. Alyth is a small county town offering local amenities, a range of shops, services and a primary school. Secondary schooling is found at Kirriemuir, Blairgowrie and Dundee. The area is well known as a gateway to the Cairngorms National Park. The Angus glens provide fine hill walking and Glenshee ski centre offers further recreational facilities. There are a number of golf courses in the area including three at Alyth. Alyth 2.5 miles, Kirriemuir 5 miles, Blairgowrie 8 miles, Dundee 21 miles, Perth 24 miles and Edinburgh 67 miles. All mileages are approximate. Detailed Description Quiech Mill is a traditional stone farmhouse set in a private and rural position on the banks of the River Isla and benefits from attractive scenery and a wide range of activities. The property has been modernised, has double glazing and is maintained to a high standard whilst retaining a number of traditional features including attractive fireplaces in the bedrooms. The accommodation over two storeys comprises: Ground floor - Entrance hall with staircase to first floor, drawing room with large bay window, office, large open plan kitchen/sitting room with wood burning stove and rear porch with utility room and WC.