Factors Influencing Women's Participation in Political Leadership

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Special Issue the Kenya Gazette

SPECIAL ISSUE THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered as a Newspaper at the G.P.O.) Vol. CXV_No. 64 NAIROBI, 19th April, 2013 Price Sh. 60 GAZETTE NOTICE NO. 5381 THE ELECTIONS ACT (No. 24 of 2011) THE ELECTIONS (PARLIAMENTARY AND COUNTY ELECTIONS) PETITION RULES, 2013 ELECTION PETITIONS, 2013 IN EXERCISE of the powers conferred by section 75 of the Elections Act and Rule 6 of the Elections (Parliamentary and County Elections) Petition Rules, 2013, the Chief Justice of the Republic of Kenya directs that the election petitions whose details are given hereunder shall be heard in the election courts comprising of the judges and magistrates listed and sitting at the court stations indicated in the schedule below. SCHEDULE No. Election Petition Petitioner(s) Respondent(s) Electoral Area Election Court Court Station No. BUNGOMA SENATOR Bungoma High Musikari Nazi Kombo Moses Masika Wetangula Senator, Bungoma Justice Francis Bungoma Court Petition IEBC County Muthuku Gikonyo No. 3 of 2013 Madahana Mbayah MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT Bungoma High Moses Wanjala IEBC Member of Parliament, Justice Francis Bungoma Court Petition Lukoye Bernard Alfred Wekesa Webuye East Muthuku Gikonyo No. 2 of 2013 Sambu Constituency, Bungoma Joyce Wamalwa, County Returning Officer Bungoma High John Murumba Chikati I.E.B.C Member of Parliament, Justice Francis Bungoma Court Petition Returning Officer Tongaren Constituency, Muthuku Gikonyo No. 4 of 2013 Eseli Simiyu Bungoma County Bungoma High Philip Mukui Wasike James Lusweti Mukwe Member of Parliament, Justice Hellen A. Bungoma Court Petition IEBC Kabuchai Constituency, Omondi No. 5 of 2013 Silas Rotich Bungoma County Bungoma High Joash Wamangoli IEBC Member of Parliament, Justice Hellen A. -

The Kenya Gazette

SPECIAL ISSUE THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered as a Newspaperat the G.P.O.) Vol. CXV_No.68 NAIROBI, 3rd May, 2013 Price Sh. 60 GAZETTE NOTICE No. 6117 THE ELECTIONS ACT (No. 24 of 2011) THE ELECTIONS (PARLIAMENTARY AND COUNTY ELECTIONS) PETITION RULES, 2013 THE ELECTION PETITIONS,2013 IN EXERCISE of the powers conferred by section 75 of the Elections Act and Rule 6 of the Elections (Parliamentary and County Elections) Petition Rules, 2013, the Chief Justice of the Republic of Kenya directs that the election petitions whose details are given hereunder shall be heard in the election courts comprising of the judges and magistrates listed andsitting at the court stations indicated in the schedule below. SCHEDULE No. Election Petition Petitioner(s) Respondent(s) Electoral Area Election Court Court Station No. BUNGOMA SENATOR Bungoma High Musikari Nazi Kombo Moses Masika Wetangula Senator, Bungoma County| Justice Francis Bungoma Court Petition IEBC Muthuku Gikonyo No. 3 of 2013 Madahana Mbayah MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT Bungoma High Moses Wanjala IEBC Memberof Parliament, Justice Francis Bungoma Court Petition Lukoye Bernard Alfred Wekesa Webuye East Muthuku Gikonyo No. 2 of 2013 Sambu Constituency, Bungoma Joyce Wamalwa, County Returning Officer Bungoma High John Murumba Chikati| LE.B.C Memberof Parliament, Justice Francis Bungoma Court Petition Returning Officer Tongaren Constituency, Muthuku Gikonyo No. 4 of 2013 Eseli Simiyu Bungoma County Bungoma High Philip Mukui Wasike James Lusweti Mukwe Memberof Parliament, Justice Hellen A. Bungoma Court Petition IEBC Kabuchai Constituency, Omondi No. 5 of 2013 Silas Rotich Bungoma County Bungoma High Joash Wamangoli IEBC Memberof Parliament, Justice Hellen A. -

Final Rongo CDF Strategic Plan Final 03 Copy

NATIONAL GOVERNMENT CONSTITUENCIES DEVELOPMENT FUND RONGO CONSTITUENCY STRATEGIC PLAN 2018-2022 CONSTITUENCY COUNTY ASSEMBLIES WARDS MAP i NG-CDF Rongo Constituency Strategic Plan: 2018/2022 Vision A model constituency in Kenya with highly motivated and empowered people enjoying high standards of living Mission To provide transformative leadership and coordination in the equitable and sustainable administration of the Rongo Constituency Development Fund Core Values • Hard work and Commitment • Integrity • Teamwork and Participatory Approach • Efficiency and Effectiveness • Impartiality and Equity ii NG-CDF Rongo Constituency Strategic Plan: 2018/2022 FOREWORD This Strategic Plan provides a roadmap and common development agenda for all stakeholders of the Rongo Constituency NG-CDF and on the programs that will be implemented for the years 2018-2022. In preparing this plan, considerations have been made to Vision 2030, Medium Term Plan 2018-2022, and The Big 4 Agenda of the National Government Executive. This plan is an important tool that sets priorities, helps us focus energy and resources, strengthen operations, ensure that we are working towards common goals. It will also help us establish agreement around intended outcome as well as assess and adjust our direction in response to a changing environment. The Strategic Plan articulates areas of development which demand special focus as priorities within the framework contained in the overall national government development Strategy: the National Government Constituency Development Fund (NG-CDF) Act, 2015. In this connection, issues to be focused on will be (i) Promotion of Education and Training, (ii) Access to clean Water and Sanitation Services, (iii) Ensure food and nutrition security through agri-business projects, (iv) Ensure universal health coverage, (v) Employment creation through manufacturing projects, (vi) Promotion of sports and creative talent, (vii) Enhance administration and security and (viii) Governance and Resource Mobilization. -

Special Issue the Kenya Gazette

SPECIAL ISSUE THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered as a Newspaper at the G.P.O.) Vol CXVIII—No. 54 NAIROBI, 17th May, 2016 Price Sh. 60 GAZETTE NOTICE NO. 3566 Fredrick Mutabari Iweta Representative of Persons with Disability. THE NATIONAL GOVERNMENT CONSTITUENCIES Gediel Kimathi Kithure Nominee of the Constituency DEVELOPMENT FUND ACT Office (Male) (No. 30 of 2015) Mary Kaari Patrick Nominee of the Constituency Office (Female) APPOINTMENT TIGANIA EAST CONSTITUENCY IN EXERCISE of the powers conferred by section 43(4) of the National Government Constituencies Development Fund Act, 2015, Micheni Chiristopher Male Youth Representative the Board of the National Government Constituencies Development Protase Miriti Fitzbrown Male Adult Representative Fund appoints, with the approval of the National Assembly, the Chrisbel Kaimuri Kaunga Female Youth Representative members of the National Government Constituencies Development Peninah Nkirote Kaberia . Female Adult Representative Fund Committees set out in the Schedule for a period of two years. Kigea Kinya Judith Representative of Persons with Disability SCHEDULE Silas Mathews Mwilaria Nominee of the Constituency - Office (Male) KISUMU WEST CONSTITUENCY Esther Jvlukomwa Mweteri -Nominee of the Constituency Vincent Onyango Jagongo Male Youth Representative Office (Female) Male Adult Representative Gabriel Onyango Osendo MATHIOYA CONSTITUENCY Beatrice Atieno Ochieng . Female Youth Representative Getrude Achieng Olum Female Adult Representative Ephantus -

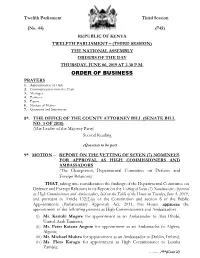

Thursday, June 06, 2019 at 2.30 P.M

Twelfth Parliament Third Session (No. 44) (745) REPUBLIC OF KENYA TWELFTH PARLIAMENT – (THIRD SESSION) THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY ORDERS OF THE DAY THURSDAY, JUNE 06, 2019 AT 2.30 P.M. ORDER OF BUSINESS PRAYERS 1. Administration of Oath 2. Communication from the Chair 3. Messages 4. Petitions 5. Papers 6. Notices of Motion 7. Questions and Statements 8*. THE OFFICE OF THE COUNTY ATTORNEY BILL (SENATE BILL NO. 3 OF 2018) (The Leader of the Majority Party) Second Reading (Question to be put) 9*. MOTION – REPORT ON THE VETTING OF SEVEN (7) NOMINEES FOR APPROVAL AS HIGH COMMISSIONERS AND AMBASSADORS (The Chairperson, Departmental Committee on Defence and Foreign Relations) THAT, taking into consideration the findings of the Departmental Committee on Defence and Foreign Relations in its Report on the Vetting of Seven (7) Nominees for Approval as High Commissioners and Ambassadors, laid on the Table of the House on Tuesday, June 4, 2019, and pursuant to Article 132(2)(e) of the Constitution and section 8 of the Public Appointments (Parliamentary Approval) Act, 2011, this House approves the appointment of the following persons as High Commissioners and Ambassadors- (i) Mr. Kariuki Mugwe for appointment as an Ambassador to Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates; (ii) Mr. Peter Katana Angore for appointment as an Ambassador to Algiers, Algeria; (iii) Mr. Michael Mubea for appointment as an Ambassador to Dublin, Ireland; (iv) Ms. Flora Karugu for appointment as High Commissioner to Lusaka Zambia; …...…/9*(Cont’d) (No. 44) THURSDAY, JUNE 06, 2019 (746) (v) Ms. Diana Kiambuthi for appointment as an Ambassador to Stockholm, Sweden; (vi) Ms. -

THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered As a Newspaper at the G.P.O.)

THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered as a Newspaper at the G.P.O.) Vol. CXX —No. 2 NAIROBI, 5th January, 2018 Price Sh. 60 CONTENTS GAZETTE NOTICES PAGE PAGE The Universities Act—Appointment 4 The Environment Management and Co-ordination Act— Environmental Impact Assessment Study Reports 17-24 The Public Finance Management Act —Uwezo Fund Committees 4-11 The Disposal of Uncollected Goods 24-25 The Mining Act—Application for Prospecting Licences 11-12 Loss of Policies 25-30 The Co-operatives Act—Extension of Liquidation Order Change of Names 30 etc 12 The Insurance Act—Extension of Moratorium 12 SUPPLEMENT No. 189 The County Governments Act—Special Sitting etc, 12-13 Legislative Supplements, 2017 The Land Registration Act—Issue of Provisional Certificates, etc 13-16 LEGAL NOTICE NO. PAGE The Trustees Act 16 —1 ne Veterinary Surgeons and Veterinary The Water Act—Approved Tariff Structure 16-17 Paraprofessionals Act, 2017 2711 [3 4 THE KENYA GAZETTE 5th January, 2018 CORRIGENDUM Pauline Chebet Member Kiptoo Elijah Member In Gazette Notice No. 7157 of 2017, Cause No. 168 of 2017, amend Jeptoo Dorcas Jepkoske Member the place of death printed as "Kirangi Sub-location" to read "Kimandi Sub-location" where it appears. SAMBURU WEST Sub-County Commissioner or Representative Member Sub- County Development Officer or Representative Member GAZETTE NOTICE No. 2 Sub- County Accountant Member THE UNIVERSITIES ACT National Government Rep—Ministry Responsible for Youth and Women Secretary (No. 42 of 2012) CDF Fund Account Manager Ex-Official Gladys Naserian Lenyarua Member GARISSA UNIVERSITY Lekulal Saddie Hosea Member APPOINTMENT Phelix Leitamparasio Member Josephine Kasaine Letiktik Member IN EXERCISE of the powers conferred by section 38 (1) (a) of the Isabella Leerte Member Universities Act. -

CONSTITUENCIES of KENYA by PROVINCE and DISTRICT NAIROBI PROVINCE Nairobi: Dagoretti Constituency Embakasi Constituency Kamukunj

CONSTITUENCIES OF KENYA BY Limuru Constituency PROVINCE AND DISTRICT Lari Constituency NAIROBI PROVINCE COAST PROVINCE Nairobi: Kilifi District: Dagoretti Constituency Bahari Constituency Embakasi Constituency Ganze Constituency Kamukunji Constituency Kaloleni Constituency Kasarani Constituency Kwale District: Langata Constituency Kinango Constituency Makadara Constituency Matuga Constituency Starehe Constituency Msambweni Constituency Westlands Constituency Lamu District: Lamu East Constituency CENTRAL PROVINCE Lamu West Constituency Malindi District: Nyandarua District: Magarini Constituency Kinangop Constituency Malindi Constituency Kipipiri Constituency Mombasa District: Ndaragwa Constituency Changamwe Constituency Ol Kalou Constituency Kisauni Constituency Nyeri District: Likoni Constituency Kieni Constituency Mvita Constituency Mathira Constituency Taita-Taveta District: Mukurweni Constituency Mwatate Constituency Nyeri Town Constituency Taveta Constituency Othaya Constituency Voi Constituency Tetu Constituency Wundanyi Constituency Kirunyaga District: Tana River District: Gichugu Constituency Bura Constituency Kerugoya/Kutus Constituency Galole Constituency Ndia Constituency Garsen Constituency Mwea Constituency Maragua District: EASTERN PROVINCE Kandara Constituency Kigumo Constituency Embu District: Maragua Constituency Manyatta Constituency Muranga District: Runyenjes Constituency Kangema Constituency Isiolo District: Kiharu Constituency Isiolo North Constituency Mathioya -

Volcxvno84.Pdf

SPECIAL ISSUE THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered as a Newspaper at the G.P.O.) Vol. CXV—No. 84 NAIROBI, 4th June, 2013 Price Sh. 60 GAZETTE NOTICE NO. 7496 Mary Nyambura Njoroge Member Joseph Mwaniki Ngure Member CONSTITUENCIES DEVELOPMENT FUND ACT 2013 Suleiman Musa Leboi Member (No. 30 of 2013) Joshua Kimani Gitau Member Moses Kiptoo Kirui Member IN EXERCISE of powers conferred by section 24 (4) of the Constituencies Development Fund Act 2013, the Cabinet Secretary SOTIK CONSTITUENCY Ministry of Devolution and Planning gazettes the following members of Constituency Development Fund Committees in various Joseph Kipngeno Kirui Chairman constituencies as outlined below for a period of three (3) years, with Fund Account Manager Sotik Ex-officio Member (Secretary) effect from 31st May, 2013. Deputy County Commissioner National Government Official (Member) NAKURU TOWN EAST CONSTITUENCY Kiprotich Langat Member Vincent Kiumbuku Matheah Chairman Reuben Paul Kipkoech Korir Member Fund Account Manager, Nakuru Ex-officio Member (Secretary) Leah Chepkurui Terer Member Town East HellenCherono Langat Member Deputy County Commissioner National Government Official Winnie Chelangat Rotich Member (Member) Hellen Chepngetich Member Antony Otieno Oduor Member Joseph Kipkirui Bett Member Nicodemus Onserio Akiba Member Peris Wambui Member BOMET EAST CONSTITUENCY Susan Wangechi Macharia Member Fatuma Al-Hajji Yusuf Member Robert Langat Chairman Lawrence Mwangi Kibogo Member Fund Account Manager Bomet East Ex-officio Member (Secretary) Samuel Njubi Muhindi Member Deputy County Commissioner National Government Official (Member) MOLO CONSTITUENCY Wilfred Too Member Samuel Karanja Muhunyu Chairman John K. Ruto Member Fund Account Manager, Molo Ex-officio Member (Secretary) Hellen Chepngeno Member Deputy County Commissioner National Government Official Beatrice Chepkorir Member (Member) Margaret C. -

The Kenya Gazette

SPECIAL ISSUE THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered as a Newspaperat the G.P.O.) Vol. CXV_No.64 NAIROBI, 19th April, 2013 Price Sh. 60 GAZETTE NOTICE No. 5381 THE ELECTIONS ACT (No. 24 of 2011) THE ELECTIONS (PARLIAMENTARY AND COUNTY ELECTIONS) PETITION RULES, 2013 ELECTION PETITIONS,2013 IN EXERCISE of the powers conferred by section 75 of the Elections Act and Rule 6 of the Elections (Parliamentary and County Elections) Petition Rules, 2013, the Chief Justice of the Republic of Kenya directs that the election petitions whose details are given hereunder shall be heard in the election courts comprising of the judges and magistrates listed andsitting at the court stations indicated in the schedule below. SCHEDULE No. Election Petition Petitioner(s) Respondent(s) Electoral Area Election Court Court Station No. BUNGOMA SENATOR Bungoma High Musikari Nazi Kombo Moses Masika Wetangula Senator, Bungoma Justice Francis Bungoma Court Petition IEBC County Muthuku Gikonyo No. 3 of 2013 Madahana Mbayah MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT Bungoma High Moses Wanjala IEBC Memberof Parliament, Justice Francis Bungoma Court Petition Lukoye Bernard Alfred Wekesa Webuye East Muthuku Gikonyo No. 2 of 2013 Sambu Constituency, Bungoma Joyce Wamalwa, County Returning Officer Bungoma High John Murumba Chikati! LE.B.C Memberof Parliament, Justice Francis Bungoma Court Petition Returning Officer Tongaren Constituency, Muthuku Gikonyo No. 4 of 2013 Eseli Simiyu Bungoma County Bungoma High Philip Mukui Wasike James Lusweti Mukwe Memberof Parliament, Justice Hellen A. Bungoma Court Petition IEBC Kabuchai Constituency, Omondi No. 5 of 2013 Silas Rotich Bungoma County Bungoma High Joash Wamangoli IEBC Memberof Parliament, Justice Hellen A. -

National Assembly

November 30, 2017 PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES 1 NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OFFICIAL REPORT Thursday, 30th November 2017 The House met at 2.30 p.m. [The Speaker (Hon. Muturi) in the Chair] PRAYERS PAPERS LAID Hon. A.B. Duale: Hon. Speaker, I beg to lay the following Papers on the Table of the House, today, Thursday, November 30, 2017: The List of Nominees to five National Government Constituencies Development Fund (NG-CDF) Committees from the National Government Constituencies Development Fund Board. The Centre for Advocacy against Alcohol and Drug Abuse (CAADA) Observation Report on the repeat presidential election in Kenya, October, 2017. The Annual Report and Financial Statement of the University of Eldoret for the year ended 30th June 2016. The Reports of the Auditor-General on the financial statements in respect of the following institutions for the year ended 30th June 2017 and the certificates therein: (a) The Central Bank of Kenya (CBK); and (b) East African Portland Cement Company Limited. The Reports of the Auditor-General on the financial statements in respect of the following institutions for the year ended 30th June 2016 and the certificates therein: (a) Kenyatta International Convention Centre (KICC); and (b) Kenya Broadcasting Corporation (KBC) The Reports of the Auditor-General on the financial statements in respect of the following constituencies for the year ended 30th June 2016, and the certificates therein: (a) Makueni Constituency; (b) Kitui West Constituency; (c) Kitui Rural Constituency; (d) Kitui South Constituency; (e) Kitui Central Constituency; (f) Turkana Central Constituency; (g) Endebess Constituency; (h) Kapseret Constituency; (i) Turkana West Constituency; (j) Manyatta Constituency; Disclaimer: The electronic version of the Official Hansard Report is for information purposes only. -

National Assembly

June 19, 2019 PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES 1 NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OFFICIAL REPORT Wednesday, 19th June 2019 The House met at 9.30 a.m. [The Deputy Speaker (Hon. Moses Cheboi) in the Chair] PRAYERS QUORUM Hon. Deputy Speaker: Hon. Members, we do not seem to have the required quorum. I, therefore, order that the Quorum Bell be rung for 10 minutes. (The Quorum Bell was rung) Order, Members! You can now take your seats. We have the required quorum and, therefore, business will begin. Hon. Members, the systems are faulty. So, we will see ways of trying to make sure that business progresses unhindered. In the meantime, I am informed that the system will be coming up quite soon. For the time being, we will organise other means of communication. ORDINARY QUESTIONS Question No. 274/2019 HARASSMENT OF STAFF BY ADC MANAGEMENT Hon. Deputy Speaker: I am informed that the honourable Member had requested for deferment of this particular Question. The Member is bereaved following the passing away of a relative. Therefore, we will put it at the next available and convenient time for both the Member and the House. (Question deferred) Next is the Member for Baringo Central, Hon. Kandie. Disclaimer: The electronic version of the Official Hansard Report is for information purposes only. A certified version of this Report can be obtained from the Hansard Editor. June 19, 2019 PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES 2 Question No. 275/2019 REDUCTION OF POLICE ROADBLOCKS ALONG NAIROBI-NAKURU HIGHWAY Hon. Joshua Kandie (Baringo Central, MCCP): Hon. Speaker, I rise to ask the Cabinet Secretary for Interior and Coordination of national Government: (i) whether he is aware that there are numerous police roadblocks manning the Nairobi-Nakuru Highway which end up disrupting traffic flow and greatly inconveniencing motorists and traders; and, (ii) what measures the Ministry is putting in place to ensure that traffic flow is enhanced along the Nairobi-Nakuru Highway and the number of road blocks is minimised. -

IEBC Report on Constituency and Ward Boundaries

REPUBLIC OF KENYA THE INDEPENDENT ELECTORAL AND BOUNDARIES COMMISSION PRELIMINARY REPORT ON THE FIRST REVIEW RELATING TO THE DELIMITATION OF BOUNDARIES OF CONSTITUENCIES AND WARDS 9TH JANUARY 2012 1 CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE ............................................................................................................................................... 8 BACKGROUND INFORMATION ...................................................................................................................... 8 1.1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 8 1.2. System and Criteria in Delimitation .............................................................................................. 9 1.3. Objective ....................................................................................................................................... 9 1.4. Procedure ...................................................................................................................................... 9 1.5. Boundary Delimitation In Kenya: Historical Perspective ............................................................. 11 1.5.1 An Overview of Boundary Delimitation in Kenya ........................................................................... 11 CHAPTER TWO ............................................................................................................................................ 14 LEGAL FRAMEWORK FOR THE DELIMITATION OF BOUNDARIES