Family and Politics: Not Just a Congress-Specific Problem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

You Have Made It to Phase 3 of ET Campus Stars 4.0. Now Get Ready

CONGRATULATIONS TO THE SHORTLISTED CANDIDATES You have made it to Phase 3 of ET Campus Stars 4.0. Now get ready for an exciting online assessment. Phase 3 is a Group Exercise and Leadership Competency Index Test that will evaluate you on your inter-personal abilities, group dynamics skills, leadership traits, and personality attributes. Please note the next steps: The online session details (including date & time) for Phase 3 assessment would be shared with you directly over the email. The shortlisted candidates have to share their details for verification, such as: •Name •Registered mobile number •College name •College ID card photo •Engineering batch •Current engineering year Please mail the above details at [email protected] latest by 29 June 2021. The list is in alphabetical order and does not endorse/promote any rank/marks Name College City A Benjimen BV Raju Institute of Technology Narsapur Sri Padmavati Mahila Visvavidyalayam - College A.Divija Sri Tirupati of Engineering Gautam Buddha University - College of Aadarsh Kumar Shrivastav Greater Noida Engineering Aadya Srivastava Kalinga Institute of Industrial Technology Bhubaneshwar Oriental Institute of Science & Technology - Aakarsh Nema Bhopal Bhopal Aakash Garg Maharaja Agrasen Institute of Technology Delhi Aakash Ravindra Shinde NBN sinhgad school of Engineering - Pune Pune Aakash Yadav IMS Engineering College Ghaziabad Cummins College of Engineering for Women - Aaliyah Ahmed Pune Pune Chandigarh Group of Colleges - College of Aarju Tripathi Greater Mohali Engineering Lovely -

29 April Page 1

Evening daily Imphal Times Regd.No. MANENG /2013/51092 Volume 6, Issue 432 Sunday, April 28, 2019 Maliyapham Palcha kumsing 3416 Cyclone FANI likely to hit North Chief Minister N. Biren inspect Chadong East including Manipur tomorrow incident site; announces ban on unauthorized IT News boat at tourism related spot (with inputs from PIB) Imphal, April 29, IT News Imphal, April 29, The Cyclonic Storm FANI, which has its root at Bay of Chief Minister N. Birenshing Bengal is likely to hit the today announced banned to North Eastern states of India the use of unauthorized local including Manipur by the made boat at lakes which are evening of May 1, PIB report tourism related sites of the says as per notification by the state. The announcement was Ministry of Earth Science. A made after inspecting the freak storm possibly an impact Ramrei/Chadong Village today of the Cyclonic FANI morning where three persons yesterday killed 3 persons including a woman were killed including a woman while in yesterday freak storm while enjoying Boat ride at Chadong they were enjoying boat ride. artificial lake. Many trees and The fierce storm that lasted for houses were also destroyed at Bengal & neighbourhood hours and into a Very Severe around 30 minutes blown the various places in the nearly 30 moved northwards with a Cyclonic Storm duringboats that the three were riding minutes deadly storm. Report speed of about 04 kmph in last subsequent 24 hours. It is very and as it turn upside-down said that wind speed reached six hours and lay centred at likely to move bodies the trio could not be 50-60 km per hour and came 0830 hrs IST of 29th April, 2019 northwestwards till May 1 found till today morning. -

Paper Teplate

Volume-03 ISSN: 2455-3085 (Online) Issue-09 RESEARCH REVIEW International Journal of Multidisciplinary September-2018 www.rrjournals.com [UGC Listed Journal] Succession planning in Politics: A Study in Indian context 1Dr. Ella Mittal & *2Parvinder Kaur 1Assistant professor, Department of Basic & Applied sciences, Punjabi university Patiala (India) *2Research scholar, Department of Basic & Applied sciences, Punjabi university Patiala (India) ARTICLE DETAILS ABSTRACT Article History The present study is about the succession planning in politics. The study traced the dynasty Published Online: 07 September 2018 of succession in various political parties. Political parties at central and state level are discussed in order to examine the succession planning among the political families. Politics is Keywords considered as business rather than a profession. BJP and regional parties are seen as legacy, Political dynasty, Political blaming Congress for family succession as their culture but have also proliferated their parties, Succession planning families in heading chief positions. Nowadays politics of India is passing through the *Corresponding Author transition and „promoting the family‟ appears to be a consistent part of their life. Leaders need Email: saini.parvinder80[at]gmail.com to change their behaviour of selfishness in order to boost the country to grow and prosper without any hindrance of corruption. 1. Introduction responsibility to ensure the „stability of tenure of personnel‟. Fayol believed that key positions would end being occupied by Succession planning is a process of thinking and unskilled or ill-prepared people if the need is ignored earlier at assuming new incumbent as a successor of the key position in proper time (Rothwell 2001). -

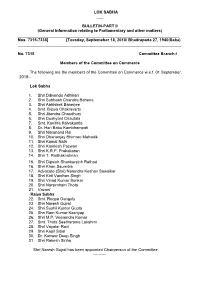

LOK SABHA ___ BULLETIN-PART II (General Information Relating To

LOK SABHA ___ BULLETIN-PART II (General Information relating to Parliamentary and other matters) ________________________________________________________________________ Nos. 7315-7338] [Tuesday, Septemeber 18, 2018/ Bhadrapada 27, 1940(Saka) _________________________________________________________________________ No. 7315 Committee Branch-I Members of the Committee on Commerce The following are the members of the Committee on Commerce w.e.f. 01 September, 2018:- Lok Sabha 1. Shri Dibyendu Adhikari 2. Shri Subhash Chandra Baheria 3. Shri Abhishek Banerjee 4. Smt. Bijoya Chakravarty 5. Shri Jitendra Chaudhury 6. Shri Dushyant Chautala 7. Smt. Kavitha Kalvakuntla 8. Dr. Hari Babu Kambhampati 9. Shri Nityanand Rai 10. Shri Dhananjay Bhimrao Mahadik 11. Shri Kamal Nath 12. Shri Kamlesh Paswan 13. Shri K.R.P. Prabakaran 14. Shri T. Radhakrishnan 15. Shri Dipsinh Shankarsinh Rathod 16. Shri Khan Saumitra 17. Advocate (Shri) Narendra Keshav Sawaikar 18. Shri Kirti Vardhan Singh 19. Shri Vinod Kumar Sonkar 20. Shri Narsimham Thota 21. Vacant Rajya Sabha 22. Smt. Roopa Ganguly 23. Shri Naresh Gujral 24. Shri Sushil Kumar Gupta 25. Shri Ram Kumar Kashyap 26. Shri M.P. Veerendra Kumar 27. Smt. Thota Seetharama Lakshmi 28. Shri Vayalar Ravi 29. Shri Kapil Sibal 30. Dr. Kanwar Deep Singh 31. Shri Rakesh Sinha Shri Naresh Gujral has been appointed Chairperson of the Committee. ---------- No.7316 Committee Branch-I Members of the Committee on Home Affairs The following are the members of the Committee on Home Affairs w.e.f. 01 September, 2018:- Lok Sabha 1. Dr. Sanjeev Kumar Balyan 2. Shri Prem Singh Chandumajra 3. Shri Adhir Ranjan Chowdhury 4. Dr. (Smt.) Kakoli Ghosh Dastidar 5. Shri Ramen Deka 6. -

Existence of Glass Ceiling in India

International Journal of Research in Engineering, Science and Management 120 Volume-3, Issue-3, March-2020 www.ijresm.com | ISSN (Online): 2581-5792 Existence of Glass Ceiling in India Niraj Bharambe1, Sanjana Bhangale2 1Assistant Professor, Department of Human Resource, Shri D. D. Vispute College of Science Commerce and Management, Panvel, India 2Assistant Professor, Dept. of IT & CS, Pillai’s College of Arts Commerce and Management, Panvel, India Abstract: India is that the country within which unity within the towards family and career. Firstly, prime management diversity exits twenty-nine states with completely different concentrates on the on top of problems relating to ladies when religions, completely different customs, and completely different searching for the performance of the ladies at the geographical languages however the standing of girls in each state rather like similar in every term. the current standing ladies in Bharat is point at the time of the appraisal or promotion that is immoral. extremely sophisticated wherever some women are on the list of Since 1970, the definition of the ladies has been incessantly prime CEOs and politics. But, on the opposite hand, no correct dynamic in each field like politics, corporate, public sector, etc. facilities on the market for continued their education. Bharat still, Male invariably dominates the feminine. There ar could be a country wherever men and ladies are equal in rights distinguishes between male {and feminine and feminine} as an however in some cases, ladies bring home the bacon but a person example rather like that pink is that the color of female and blue below identical parameter. -

Modi's New India

Kolkata Seminar Invitation On 17th August, 2019 at 2 p.m. at Bharat Sabha Hall (Indian Association Hall, B. B. Ganguli Street, near its Crossing with Chittaranjan Avenue, Kolkata) Dear Friends, Indian Renaissance Institute and Indian Radical Humanist Association, West Bengal Unit are going to jointly organise a seminar on: 1. 2019 Election: BJP's Victory - A Challenge to Secular Polity, & 2. Party-less Democracy at Bharat Sabha Hall, Kolkata. The Speakers include Mr. Jahar Sarkar, IAS (Retd.) & former CEO, Doordarshan, Prof. Apurba Mukhopadhyay, former Prof. Bardhaman University & was attached to the Netaji Research Bureau, Mr. Pravin Patel, a social activist of fame, Dr. Bhabani Dikshit, journalist & IRI Member, Mr. N.D. Pancholi, well known Civil Rights lawyer & one of the Vice-Chairmen, IRI, Mr. Ajit Bhattacharyya, Life Trustee, IRI and Ms. Sangeeta Mall, former Managing Editor, The Radical Humanist. Prof. Miratun Nahar will preside over the 1st Session & Prof. Manju Ray over the 2nd. You are cordially invited to attend the seminar. For more details, please contact: Mr. Ajit Bhattacharyya. (M) 9433224517 Mahi Pal Singh Secretary, IRI In Memory of George Fernandes: His write up ‘On the threshold of a fascist state’: Preface: On the threshold of a fascist state George Fernandes (The recent 3rd June was remembered as privilege of associating with him in trade birth anniversary of veteran political leader unions movements as part of HMS (Hind George Fernandes who recently died this Mazdoor Sabha) during seventies. Generally year. Many friends paid glowing tributes to he came forcefully in support of civil liberties him. The eminent journalist Shri Jaishankar and democratic movements. -

Committee Matrices

Committee Matrices Please note, *(O) next to any Country’s name marks the Observer status in that Committee. 1. UNITED NATIONS ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMME 1. Afghanistan 41. Germany 81. Russia 2. Algeria 42. Ghana 82. Rwanda 3. Angola 43. Greece 83. Mongolia 4. Argentina 44. Guinea-Bissau 84. Montenegro 5. Australia 45. Haiti 85. Morocco 6. Austria 46. Honduras 86. Namibia 7. Azerbaijan 47. Hungary 87. Nepal 8. Bahrain 48. Iceland 88. Netherland 9. Bangladesh 49. India 89. New Zealand 10. Belarus 50. Indonesia 90. Nicaragua 11. Belgium 51. Iran 91. Nigeria 12. Bosnia and Herzegovina 52. Iraq 92. Saudi Arabia 13. Botswana 53. Ireland 93. Senegal 14. Brazil 54. Israel 94. Sweden 15. Bulgaria 55. Italy 95. Switzerland 16. Burkina Faso 56. Japan 96. Syria 17. Cambodia 57. Jordan 97. Sierra Leone 18. Canada 58. Kazakhstan 98. Singapore 19. Central African Republic 59. Kenya 99. Somalia 20. Chile 60. Kuwait 100. South Africa 21. China 61. Kyrgyzstan 101. South Sudan 22. Costa Rica 62. Latvia 102. Spain 23. Côte d’Ivoire 63. Lebanon 103. Sri Lanka 1 of 10 24. Croatia 64. Liberia 104. Tajikistan 25. Cuba 65. Libya 105. Thailand 26. Czech Republic 66. Luxembourg 106. Togo 27. Democratic Republic of Congo 67. Macedonia 107. Tunisia 28. Democratic Republic of Korea 68. Malaysia 108. Turkey 29. Denmark 69. Maldives 109. Turkmenistan 30. Djibouti 70. Mauritius 110. Ukraine 31. Dominican Republic 71. Mexico 111. United Arab Emirates 32. Egypt 72. Pakistan 112. Uganda 33. El Salvador 73. Oman 113. United Kingdom 34. Eritrea 74. Panama 114. Uruguay 35. Ethiopia 75. -

Judgment Altamas Kabir, Cji

1 REPORTABLE IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL APPELLATE JURISDICTION REVIEW PETITION (CIVIL) NO.272 OF 2007 IN WRIT PETITION (CIVIL)No.633 of 2005 AKHILESH YADAV … PETITIONER VS. VISHWANATH CHATURVEDI & ORS. … RESPONDENTS WITH REVIEW PETITION (CIVIL) NO.339 OF 2007 IN WRIT PETITION (CIVIL)No.633 of 2005 MULAYAM SINGH YADAV … PETITIONER VS. VISHWANATH CHATURVEDI & ORS. … RESPONDENTS Page 1 2 WITH REVIEW PETITION (CIVIL) NO.347 OF 2007 IN WRIT PETITION (CIVIL)No.633 of 2005 PRATEEK YADAV … PETITIONER VS. VISHWANATH CHATURVEDI & ORS. … RESPONDENTS WITH REVIEW PETITION (CIVIL) NO.348 OF 2007 IN WRIT PETITION (CIVIL)No.633 of 2005 SMT. DIMPLE YADAV … PETITIONER VS. VISHWANATH CHATURVEDI & ORS. … RESPONDENTS Page 2 3 J U D G M E N T ALTAMAS KABIR, CJI. 1. Certain questions of fact and law were raised on behalf of the parties when the review petitions were heard. Review petitions are ordinarily restricted to the confines of the principles enunciated in Order 47 of the Code of Civil Procedure, but in this case, we gave counsel for the parties ample opportunity to satisfy us that the judgment and order under review suffered from any error apparent on the face of the record and that permitting the order to stand would occasion a failure of justice or that the judgment suffered from some material irregularity which required correction in review. The scope of a review petition is very limited and the submissions advanced were made mainly on questions of fact. As Page 3 4 has been repeatedly indicated by this Court, review of a judgment on account of some mistake or error apparent on the face of the record is permissible, but an error apparent on the face of the record has to be decided on the facts of each case as an erroneous decision by itself does not warrant a review of each decision. -

Hon'ble Shri Akhilesh Yadav Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh and Leader of the House

Hon'ble Shri Akhilesh Yadav Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh and Leader of The House Father’s Name Shri Mulayam Singh Yadav Mother’s Name Late Malti Devi Date of Birth 1st July 1973 Place of Birth Saifai , Distt Etawah (Uttar Pradesh) Marital Status Married Date of Marriage 24th Nov 1999 Spouse Smt Dimple Yadav Children Three, named Aditi and twins Arjun and Tina Actively and consistently struggling for the all-round development of the rural poor, Social Activities farmers, workers and downtrodden. Profession Agriculturist, Engineer ,Political and social worker Favourite Pastime Reading , Music and Films and recreation Educational B.E. in Civil Environment Engineering Qualification Permanent 5, Vikramaditya Marg, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh Address Official Address 5, Kalidas Marg, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh Elected to 13th Lok Sabha (Elected in bye-Election) 2000 Member, Committee on Food, Civil Supplies and Public Distribution 2000-2001 Member , Committee on Ethics 2002-2004 Member, Committee on Science & Technologies, Environment & Forests Re-elected to 14th Lok-Sabha (2nd Term) Member, Committee on Estimates Member, Committee on Urban Development 2004-2009 Member, Committee on provision of computers for MPs, offices of Parties, Officers of Lok Sabha Secretariat Member ,Science & technology, Environment & Forests(2007) 2009 Re Elected to 15th Lok-Sabha (3rd Term) Member ,Science & Technologies , Environment & Forests Member, JPC on 2G 2009-2012 Spectrum Scam Elected leader of U.P. Samajwadi Legislature party and nominated as Chief 2012, 10th March Minister 2012,15th March Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh 2012, 5 May Elected Member of Legislative Council, Uttar Pradesh Other Interests Playing and watching football matches and cricket Australia, United States, United Kingdom, China, Switzerland ,France, Austria, Foreign Visits Canada, Japan . -

4 (16Th LOK SABHA )

Election Commission of India, General Elections, 2014 (16th LOK SABHA ) 4 - LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES CONSTITUENCY Category WINNER Social Category PARTY PARTY SYMBOL MARGIN Andaman & Nicobar Islands 1 Andaman & GEN Bishnu Pada Ray GEN BJP Lotus 7812 Nicobar Islands ( 4.14 %) Andhra Pradesh 2 Adilabad ST Godam Nagesh ST TRS Car 171290 ( 16.65 %) 3 Amalapuram SC Dr Pandula Ravindra SC TDP Bicycle 120576 Babu ( 10.82 %) 4 Anakapalli GEN Muttamsetti Srinivasa GEN TDP Bicycle 47932 Rao (Avanthi) ( 4.21 %) 5 Anantapur GEN J.C. Divakar Reddi GEN TDP Bicycle 61991 ( 5.15 %) 6 Aruku ST Kothapalli Geetha ST YSRCP Ceiling Fan 91398 ( 10.23 %) 7 Bapatla SC Malyadri Sriram SC TDP Bicycle 32754 ( 2.78 %) 8 Bhongir GEN Dr. Boora Narsaiah GEN TRS Car 30544 Goud ( 2.54 %) 9 Chelvella GEN Konda Vishweshwar GEN TRS Car 73023 Reddy ( 5.59 %) 10 Chittoor SC Naramalli Sivaprasad SC TDP Bicycle 44138 ( 3.70 %) 11 Eluru GEN Maganti Venkateswara GEN TDP Bicycle 101926 Rao (Babu) ( 8.54 %) 12 Guntur GEN Jayadev Galla GEN TDP Bicycle 69111 ( 5.59 %) 13 Hindupur GEN Kristappa Nimmala GEN TDP Bicycle 97325 ( 8.33 %) 14 Hyderabad GEN Asaduddin Owaisi GEN AIMIM Kite 202454 ( 20.95 %) 15 Kadapa GEN Y.S. Avinash Reddy GEN YSRCP Ceiling Fan 190323 ( 15.93 %) 16 Kakinada GEN Thota Narasimham GEN TDP Bicycle 3431 ( 0.31 %) 17 Karimnagar GEN Vinod Kumar GEN TRS Car 204652 Boinapally ( 18.28 %) 18 Khammam GEN Ponguleti Srinivasa GEN YSRCP Ceiling Fan 12204 Reddy ( 1.04 %) 19 Kurnool GEN Butta Renuka GEN YSRCP Ceiling Fan 44131 ( 4.18 %) 20 Machilipatnam GEN Konakalla Narayana GEN TDP Bicycle 81057 Rao ( 7.15 %) 21 Mahabubabad ST Prof. -

Lok Sabha Secretariat

LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT Details of expenditure incurred on HS/HDS/LOP/MP(s)* During the Period From 01/11/2014 To 30/11/2014 Office Salary for Arrears(if SL ICNO Name of MP/ Salary Constituency Travelling/ Expense/ Available) State Allowance Secretarial daily Sumptury Assistant Allowence Allowance 160001 Shri Godam Nagesh 1 50000 45000 15000 30000 0 0 Andhra Pradesh 160002 Shri Balka Suman 2 50000 45000 15000 30000 0 0 Andhra Pradesh 160003 Shri Vinod kumar 3 50000 45000 15000 30000 140605 Boianapalli 0 Andhra Pradesh 160004 Smt. Kalvakuntla Kavitha 4 50000 45000 15000 30000 1064644 0 Andhra Pradesh 160005 Shri Bheemrao 5 50000 45000 15000 30000 498828 Baswanthrao Patil 0 Andhra Pradesh 160006 Shri Kotha Prabhakar 6 50000 45000 15000 75000 0 Reddy 0 Andhra Pradesh 160007 Ch.Malla Reddy 7 50000 45000 15000 30000 25986 0 Andhra Pradesh 160008 Shri Bandaru Dattatreya 8 0 0 0 0 0 0 Andhra Pradesh 160009 Shri Owaisi Asaduddin 9 50000 45000 15000 30000 0 0 Andhra Pradesh 160010 Shri Konda Vishweshar 10 50000 45000 15000 30000 0 Reddy 0 Andhra Pradesh 160011 Shri A.P.Jithender Reddy 11 50000 45000 15000 30000 425466 0 Andhra Pradesh 160012 Shri Yellaiah Nandi 12 50000 45000 15000 30000 0 0 Andhra Pradesh 160013 Shri Guntha Sukender 13 50000 45000 15000 30000 425437 Reddy 0 Andhra Pradesh 160014 Dr.Boora Narsaiah Goud 14 50000 45000 15000 30000 68974 0 Andhra Pradesh 160015 Shri Kadiyam Srihari 15 50000 45000 15000 30000 112775 0 Andhra Pradesh 160016 Prof. Azmeera Seetaram 16 50000 45000 15000 30000 326937 Naik 0 Andhra Pradesh 160017 ShriPonguleti Srinivasa 17 50000 45000 15000 30000 298637 Reddy 0 Andhra Pradesh LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT Details of expenditure incurred on HS/HDS/LOP/MP(s)* During the Period From 01/11/2014 To 30/11/2014 Office Salary for Arrears(if SL ICNO Name of MP/ Salary Constituency Travelling/ Expense/ Available) State Allowance Secretarial daily Sumptury Assistant Allowence Allowance 160018 Smt. -

Page1.Qxd (Page 1)

DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU TUESDAY, APRIL 30, 2019 (PAGE 11) From page 1 Immigration system server Decision on alleged violations of model 64 pc turnout in 4th phase, Life-imprisonment to 3 in murder case faces tech glitches, 6 6443 when he was on his way to that the accused persons will flights delayed code by Modi, Rahul, Shah today violence in WB Kathua from Jammu in a very mend their ways or change their NEW DELHI, Apr 29: Birbhum seat, leaving several Samajwadi Party’s alleged that brutal manner on April 28, 2005. life as good citizen". NEW DELHI, Apr 29: The local poll authorities in EC's guidelines because he had people injured. many EVMs malfunctioned and After hearing APP Davinder "In fact apart from the inci- Maharashtra are learnt to have not sought votes for any party, an Hundreds of passengers The Election Commission In Barabani, BJP candidate in Kannauj, from where SP Sharma for the State whereas dent in question, prosecution told the EC here that Prime official said the matter is before had a harrowing time at the will take a decision on com- from Asansol and Union chief Akhislesh Yadav’s wife Advocate A Salathia for the could not establish any such past Minister Narendra Modi's EC and it would decide on it Delhi airport early today as plaints of model code violations Minister Babul Supriyo’s vehi- and sitting MP Dimple Yadav is accused, the court observed, criminal history against the con- remarks asking first-time voters Tuesday. the immigration system serv- by Prime Minister Narendra cle was vandalised allegedly by contesting, several party work- "the accused persons have com- victs/accused though the APP to dedicate their vote to those A decision on Shah's reported er faced technical issues for Modi, BJP chief Amit Shah and TMC workers outside a polling ers were prevented from com- mitted the murder in very brutal has submitted during the argu- who carried out the Balakot air remarks on 'Modi ji ki vayu sena' around one-and-a-half hours, Congress president Rahul station while in Dubrajpur area ing out of their homes to vote.