The Political Impact of Monetary Shocks Remains Under-Explored in the Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

You Have Made It to Phase 3 of ET Campus Stars 4.0. Now Get Ready

CONGRATULATIONS TO THE SHORTLISTED CANDIDATES You have made it to Phase 3 of ET Campus Stars 4.0. Now get ready for an exciting online assessment. Phase 3 is a Group Exercise and Leadership Competency Index Test that will evaluate you on your inter-personal abilities, group dynamics skills, leadership traits, and personality attributes. Please note the next steps: The online session details (including date & time) for Phase 3 assessment would be shared with you directly over the email. The shortlisted candidates have to share their details for verification, such as: •Name •Registered mobile number •College name •College ID card photo •Engineering batch •Current engineering year Please mail the above details at [email protected] latest by 29 June 2021. The list is in alphabetical order and does not endorse/promote any rank/marks Name College City A Benjimen BV Raju Institute of Technology Narsapur Sri Padmavati Mahila Visvavidyalayam - College A.Divija Sri Tirupati of Engineering Gautam Buddha University - College of Aadarsh Kumar Shrivastav Greater Noida Engineering Aadya Srivastava Kalinga Institute of Industrial Technology Bhubaneshwar Oriental Institute of Science & Technology - Aakarsh Nema Bhopal Bhopal Aakash Garg Maharaja Agrasen Institute of Technology Delhi Aakash Ravindra Shinde NBN sinhgad school of Engineering - Pune Pune Aakash Yadav IMS Engineering College Ghaziabad Cummins College of Engineering for Women - Aaliyah Ahmed Pune Pune Chandigarh Group of Colleges - College of Aarju Tripathi Greater Mohali Engineering Lovely -

306 RAJYA SABHA TUESDAY, the 18TH FEBRUARY, 2014 (The

RAJYA SABHA TUESDAY, THE 18TH FEBRUARY, 2014 (The Rajya Sabha met in the Parliament House at 11-00 a.m.) #11-02 a.m. (The House adjourned at 11-02 a.m. and re-assembled at 12-00 Noon) 1. Starred Questions Answers to Starred Question Nos. 341 to 360 were laid on the Table. 2. Unstarred Questions Answers to Unstarred Question Nos. 2487 to 2641 were laid on the Table. 12-00 Noon. 3. Papers Laid on the Table Shri Ghulam Nabi Azad (Minister of Health and Family Welfare and Minister of Water Resources) laid on the Table:- I. A copy each (in English and Hindi) of the following Notifications of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (Department of Health and Family Welfare), under Section 34 of the Pre-conception and Pre-natal Diagnostic Technologies (Prohibition of Sex Selection) Act, 1994:— (1) G.S.R. 13 (E), dated the 10th January, 2014, publishing the Pre- conception and Pre-natal Diagnostic Techniques (Prohibition of Sex Selection) Amendment Rules, 2014. (2) G.S.R. 14 (E), dated the 10th January, 2014, publishing the Pre- conception and Pre-natal Diagnostic Techniques (Prohibition of Sex Selection) (Six Months Training) Rules, 2014. II. A copy each (in English and Hindi) of the following papers:— (i) (a) Annual Report and Accounts of the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI), New Delhi, for the year 2012-13, together with the Auditor's Report on the Accounts. (b) Review by Government on the working of the above Authority. (c) Statement giving reasons for the delay in laying the papers mentioned at (i) (a) above. -

Events; Appointments; Etc - August 2013

Events; Appointments; Etc - August 2013 BACK APPOINTED; ELECTED; Etc. Hassan Rowhani: He has been elected as the President of Iran. Raghuram Rajan: Chief Economic Adviser to UPA government, he has been appointed as the Governor of Reserve Bank Of India (RBI). Dilip Trivedi: Senior IPS officer, he has been appointed as the Chief of the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF). DISTINGUISHED VISITORS G.L. Peiris: External Affairs Minister of Sri Lanka. He came to invite Prime Minister Manmohan Singh for the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meet in Colombo in November. Prime Minister Singh, during his talk with Mr Peiris, asked Sri Lanka to stand by its commitment not to dilute the 13th Amendment on devolution of powers to the provinces and sought an early repatriation of Indian fishermen presently in the custody of the Lankan authorities. Mohammad Karim Khalili: Vice President o Afghanistan. During his three-day visit security issues and trade and other bilateral issues were discussed. Nuri al-Maliki: Prime Minister of Iraq. The visit was the first high-level bilateral trip in 38 years. Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi had visited Iraq in 1975. Maliki’s trip saw India and Iraq sign an agreement on energy cooperation. Tshering Tobgay: Prime Minister of Bhutan. This was his first overseas visit after assuming office in July 2013. He briefed New Delhi on the talks between his country and China over their boundary dispute, which has strategic implications for India’s security. DIED Pandit Raghunath Panigrahi: Eminent Indian classical singer and music director from Odisha, better known as a noted vocalist of Jayadeva’s ‘Gita Govind’, he died on 25 August 2013. -

29 April Page 1

Evening daily Imphal Times Regd.No. MANENG /2013/51092 Volume 6, Issue 432 Sunday, April 28, 2019 Maliyapham Palcha kumsing 3416 Cyclone FANI likely to hit North Chief Minister N. Biren inspect Chadong East including Manipur tomorrow incident site; announces ban on unauthorized IT News boat at tourism related spot (with inputs from PIB) Imphal, April 29, IT News Imphal, April 29, The Cyclonic Storm FANI, which has its root at Bay of Chief Minister N. Birenshing Bengal is likely to hit the today announced banned to North Eastern states of India the use of unauthorized local including Manipur by the made boat at lakes which are evening of May 1, PIB report tourism related sites of the says as per notification by the state. The announcement was Ministry of Earth Science. A made after inspecting the freak storm possibly an impact Ramrei/Chadong Village today of the Cyclonic FANI morning where three persons yesterday killed 3 persons including a woman were killed including a woman while in yesterday freak storm while enjoying Boat ride at Chadong they were enjoying boat ride. artificial lake. Many trees and The fierce storm that lasted for houses were also destroyed at Bengal & neighbourhood hours and into a Very Severe around 30 minutes blown the various places in the nearly 30 moved northwards with a Cyclonic Storm duringboats that the three were riding minutes deadly storm. Report speed of about 04 kmph in last subsequent 24 hours. It is very and as it turn upside-down said that wind speed reached six hours and lay centred at likely to move bodies the trio could not be 50-60 km per hour and came 0830 hrs IST of 29th April, 2019 northwestwards till May 1 found till today morning. -

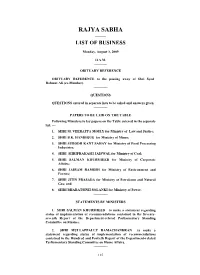

Rajya Sabha —— List of Business

RAJYA SABHA —— LIST OF BUSINESS Monday, August 3, 2009 11A.M. ——— OBITUARY REFERENCE OBITUARY REFERENCE to the passing away of Shri Syed Rahmat Ali (ex-Member). ———— QUESTIONS QUESTIONS entered in separate lists to be asked and answers given. ———— PAPERS TO BE LAID ON THE TABLE Following Ministers to lay papers on the Table entered in the separate list: — 1. SHRI M. VEERAPPA MOILY for Ministry of Law and Justice; 2. SHRI B.K. HANDIQUE for Ministry of Mines; 3. SHRI SUBODH KANT SAHAY for Ministry of Food Processing Industries; 4. SHRI SHRIPRAKASH JAISWAL for Ministry of Coal; 5. SHRI SALMAN KHURSHEED for Ministry of Corporate Affairs; 6. SHRI JAIRAM RAMESH for Ministry of Environment and Forests; 7. SHRI JITIN PRASADA for Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas; and 8. SHRI BHARATSINH SOLANKI for Ministry of Power. ———— STATEMENTS BY MINISTERS 1. SHRI SALMAN KHURSHEED to make a statement regarding status of implementation of recommendations contained in the Seventy- seventh Report of the Department-related Parliamentary Standing Committee on Finance. 2. SHRI MULLAPPALLY RAMACHANDRAN to make a statement regarding status of implementation of recommendations contained in the Hundred and Fortieth Report of the Department-related Parliamentary Standing Committee on Home Affairs. ———— 185 LEGISLATIVE BUSINESS Bill for introduction The Judges 1. SHRI M. VEERAPPA MOILY to move for leave to introduce a (Declaration of Bill to provide for the declaration of assets and liabilities by the Judges. Assets and Liabilities) ALSO to introduce the Bill. Bill, 2009 Bill for consideration and passing The 2. SHRI M. VEERAPPA MOILY to move that the Bill further to Constitution amend the Constitution of India, be taken into consideration. -

Paper Teplate

Volume-03 ISSN: 2455-3085 (Online) Issue-09 RESEARCH REVIEW International Journal of Multidisciplinary September-2018 www.rrjournals.com [UGC Listed Journal] Succession planning in Politics: A Study in Indian context 1Dr. Ella Mittal & *2Parvinder Kaur 1Assistant professor, Department of Basic & Applied sciences, Punjabi university Patiala (India) *2Research scholar, Department of Basic & Applied sciences, Punjabi university Patiala (India) ARTICLE DETAILS ABSTRACT Article History The present study is about the succession planning in politics. The study traced the dynasty Published Online: 07 September 2018 of succession in various political parties. Political parties at central and state level are discussed in order to examine the succession planning among the political families. Politics is Keywords considered as business rather than a profession. BJP and regional parties are seen as legacy, Political dynasty, Political blaming Congress for family succession as their culture but have also proliferated their parties, Succession planning families in heading chief positions. Nowadays politics of India is passing through the *Corresponding Author transition and „promoting the family‟ appears to be a consistent part of their life. Leaders need Email: saini.parvinder80[at]gmail.com to change their behaviour of selfishness in order to boost the country to grow and prosper without any hindrance of corruption. 1. Introduction responsibility to ensure the „stability of tenure of personnel‟. Fayol believed that key positions would end being occupied by Succession planning is a process of thinking and unskilled or ill-prepared people if the need is ignored earlier at assuming new incumbent as a successor of the key position in proper time (Rothwell 2001). -

An End to Antisemitism!

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds An End to Antisemitism! Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman Volume 5 Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman ISBN 978-3-11-058243-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-067196-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-067203-9 DOI https://10.1515/9783110671964 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Library of Congress Control Number: 2021931477 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, Lawrence H. Schiffman, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com Cover image: Illustration by Tayler Culligan (https://dribbble.com/taylerculligan). With friendly permission of Chicago Booth Review. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com TableofContents Preface and Acknowledgements IX LisaJacobs, Armin Lange, and Kerstin Mayerhofer Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds: Introduction 1 Confronting Antisemitism through Critical Reflection/Approaches -

The Journal of Parliamentary Information

The Journal of Parliamentary Information VOLUME LIX NO. 1 MARCH 2013 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI CBS Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd. 24, Ansari Road, Darya Ganj, New Delhi-2 EDITORIAL BOARD Editor : T.K. Viswanathan Secretary-General Lok Sabha Associate Editors : P.K. Misra Joint Secretary Lok Sabha Secretariat Kalpana Sharma Director Lok Sabha Secretariat Assistant Editors : Pulin B. Bhutia Additional Director Lok Sabha Secretariat Parama Chatterjee Joint Director Lok Sabha Secretariat Sanjeev Sachdeva Joint Director Lok Sabha Secretariat © Lok Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi THE JOURNAL OF PARLIAMENTARY INFORMATION VOLUME LIX NO. 1 MARCH 2013 CONTENTS PAGE EDITORIAL NOTE 1 ADDRESSES Addresses at the Inaugural Function of the Seventh Meeting of Women Speakers of Parliament on Gender-Sensitive Parliaments, Central Hall, 3 October 2012 3 ARTICLE 14th Vice-Presidential Election 2012: An Experience— T.K. Viswanathan 12 PARLIAMENTARY EVENTS AND ACTIVITIES Conferences and Symposia 17 Birth Anniversaries of National Leaders 22 Exchange of Parliamentary Delegations 26 Bureau of Parliamentary Studies and Training 28 PARLIAMENTARY AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENTS 30 PRIVILEGE ISSUES 43 PROCEDURAL MATTERS 45 DOCUMENTS OF CONSTITUTIONAL AND PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST 49 SESSIONAL REVIEW Lok Sabha 62 Rajya Sabha 75 State Legislatures 83 RECENT LITERATURE OF PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST 85 APPENDICES I. Statement showing the work transacted during the Twelfth Session of the Fifteenth Lok Sabha 91 (iv) iv The Journal of Parliamentary Information II. Statement showing the work transacted during the 227th Session of the Rajya Sabha 94 III. Statement showing the activities of the Legislatures of the States and Union Territories during the period 1 October to 31 December 2012 98 IV. -

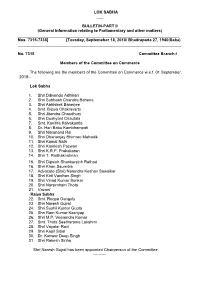

LOK SABHA ___ BULLETIN-PART II (General Information Relating To

LOK SABHA ___ BULLETIN-PART II (General Information relating to Parliamentary and other matters) ________________________________________________________________________ Nos. 7315-7338] [Tuesday, Septemeber 18, 2018/ Bhadrapada 27, 1940(Saka) _________________________________________________________________________ No. 7315 Committee Branch-I Members of the Committee on Commerce The following are the members of the Committee on Commerce w.e.f. 01 September, 2018:- Lok Sabha 1. Shri Dibyendu Adhikari 2. Shri Subhash Chandra Baheria 3. Shri Abhishek Banerjee 4. Smt. Bijoya Chakravarty 5. Shri Jitendra Chaudhury 6. Shri Dushyant Chautala 7. Smt. Kavitha Kalvakuntla 8. Dr. Hari Babu Kambhampati 9. Shri Nityanand Rai 10. Shri Dhananjay Bhimrao Mahadik 11. Shri Kamal Nath 12. Shri Kamlesh Paswan 13. Shri K.R.P. Prabakaran 14. Shri T. Radhakrishnan 15. Shri Dipsinh Shankarsinh Rathod 16. Shri Khan Saumitra 17. Advocate (Shri) Narendra Keshav Sawaikar 18. Shri Kirti Vardhan Singh 19. Shri Vinod Kumar Sonkar 20. Shri Narsimham Thota 21. Vacant Rajya Sabha 22. Smt. Roopa Ganguly 23. Shri Naresh Gujral 24. Shri Sushil Kumar Gupta 25. Shri Ram Kumar Kashyap 26. Shri M.P. Veerendra Kumar 27. Smt. Thota Seetharama Lakshmi 28. Shri Vayalar Ravi 29. Shri Kapil Sibal 30. Dr. Kanwar Deep Singh 31. Shri Rakesh Sinha Shri Naresh Gujral has been appointed Chairperson of the Committee. ---------- No.7316 Committee Branch-I Members of the Committee on Home Affairs The following are the members of the Committee on Home Affairs w.e.f. 01 September, 2018:- Lok Sabha 1. Dr. Sanjeev Kumar Balyan 2. Shri Prem Singh Chandumajra 3. Shri Adhir Ranjan Chowdhury 4. Dr. (Smt.) Kakoli Ghosh Dastidar 5. Shri Ramen Deka 6. -

Existence of Glass Ceiling in India

International Journal of Research in Engineering, Science and Management 120 Volume-3, Issue-3, March-2020 www.ijresm.com | ISSN (Online): 2581-5792 Existence of Glass Ceiling in India Niraj Bharambe1, Sanjana Bhangale2 1Assistant Professor, Department of Human Resource, Shri D. D. Vispute College of Science Commerce and Management, Panvel, India 2Assistant Professor, Dept. of IT & CS, Pillai’s College of Arts Commerce and Management, Panvel, India Abstract: India is that the country within which unity within the towards family and career. Firstly, prime management diversity exits twenty-nine states with completely different concentrates on the on top of problems relating to ladies when religions, completely different customs, and completely different searching for the performance of the ladies at the geographical languages however the standing of girls in each state rather like similar in every term. the current standing ladies in Bharat is point at the time of the appraisal or promotion that is immoral. extremely sophisticated wherever some women are on the list of Since 1970, the definition of the ladies has been incessantly prime CEOs and politics. But, on the opposite hand, no correct dynamic in each field like politics, corporate, public sector, etc. facilities on the market for continued their education. Bharat still, Male invariably dominates the feminine. There ar could be a country wherever men and ladies are equal in rights distinguishes between male {and feminine and feminine} as an however in some cases, ladies bring home the bacon but a person example rather like that pink is that the color of female and blue below identical parameter. -

Modi's New India

Kolkata Seminar Invitation On 17th August, 2019 at 2 p.m. at Bharat Sabha Hall (Indian Association Hall, B. B. Ganguli Street, near its Crossing with Chittaranjan Avenue, Kolkata) Dear Friends, Indian Renaissance Institute and Indian Radical Humanist Association, West Bengal Unit are going to jointly organise a seminar on: 1. 2019 Election: BJP's Victory - A Challenge to Secular Polity, & 2. Party-less Democracy at Bharat Sabha Hall, Kolkata. The Speakers include Mr. Jahar Sarkar, IAS (Retd.) & former CEO, Doordarshan, Prof. Apurba Mukhopadhyay, former Prof. Bardhaman University & was attached to the Netaji Research Bureau, Mr. Pravin Patel, a social activist of fame, Dr. Bhabani Dikshit, journalist & IRI Member, Mr. N.D. Pancholi, well known Civil Rights lawyer & one of the Vice-Chairmen, IRI, Mr. Ajit Bhattacharyya, Life Trustee, IRI and Ms. Sangeeta Mall, former Managing Editor, The Radical Humanist. Prof. Miratun Nahar will preside over the 1st Session & Prof. Manju Ray over the 2nd. You are cordially invited to attend the seminar. For more details, please contact: Mr. Ajit Bhattacharyya. (M) 9433224517 Mahi Pal Singh Secretary, IRI In Memory of George Fernandes: His write up ‘On the threshold of a fascist state’: Preface: On the threshold of a fascist state George Fernandes (The recent 3rd June was remembered as privilege of associating with him in trade birth anniversary of veteran political leader unions movements as part of HMS (Hind George Fernandes who recently died this Mazdoor Sabha) during seventies. Generally year. Many friends paid glowing tributes to he came forcefully in support of civil liberties him. The eminent journalist Shri Jaishankar and democratic movements. -

Committee Matrices

Committee Matrices Please note, *(O) next to any Country’s name marks the Observer status in that Committee. 1. UNITED NATIONS ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMME 1. Afghanistan 41. Germany 81. Russia 2. Algeria 42. Ghana 82. Rwanda 3. Angola 43. Greece 83. Mongolia 4. Argentina 44. Guinea-Bissau 84. Montenegro 5. Australia 45. Haiti 85. Morocco 6. Austria 46. Honduras 86. Namibia 7. Azerbaijan 47. Hungary 87. Nepal 8. Bahrain 48. Iceland 88. Netherland 9. Bangladesh 49. India 89. New Zealand 10. Belarus 50. Indonesia 90. Nicaragua 11. Belgium 51. Iran 91. Nigeria 12. Bosnia and Herzegovina 52. Iraq 92. Saudi Arabia 13. Botswana 53. Ireland 93. Senegal 14. Brazil 54. Israel 94. Sweden 15. Bulgaria 55. Italy 95. Switzerland 16. Burkina Faso 56. Japan 96. Syria 17. Cambodia 57. Jordan 97. Sierra Leone 18. Canada 58. Kazakhstan 98. Singapore 19. Central African Republic 59. Kenya 99. Somalia 20. Chile 60. Kuwait 100. South Africa 21. China 61. Kyrgyzstan 101. South Sudan 22. Costa Rica 62. Latvia 102. Spain 23. Côte d’Ivoire 63. Lebanon 103. Sri Lanka 1 of 10 24. Croatia 64. Liberia 104. Tajikistan 25. Cuba 65. Libya 105. Thailand 26. Czech Republic 66. Luxembourg 106. Togo 27. Democratic Republic of Congo 67. Macedonia 107. Tunisia 28. Democratic Republic of Korea 68. Malaysia 108. Turkey 29. Denmark 69. Maldives 109. Turkmenistan 30. Djibouti 70. Mauritius 110. Ukraine 31. Dominican Republic 71. Mexico 111. United Arab Emirates 32. Egypt 72. Pakistan 112. Uganda 33. El Salvador 73. Oman 113. United Kingdom 34. Eritrea 74. Panama 114. Uruguay 35. Ethiopia 75.