The State of South Lanarkshire's Environment 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Lanarkshire War Memorials

Community and Enterprise Resources War memorials in South Lanarkshire For more information on our war memorials email [email protected] or phone 0303 123 1020. If you need this information in another language or format, please contact us to discuss how we can best meet your needs. Phone 0303 123 1015 or email [email protected] War memorials Ashgill War Memorial Auchentibber War Memorial Biggar War Memorial Bothwell War Memorial Braehead War Memorial Cambuslang War Memorial Carluke War Memorial (The Market) Carluke War Memorial (St Lukes Churchyard) Carmichael War Memorial Carnwath War Memorial Carstairs Junction War Memorial Carstairs Village War Memorial Coulter War Memorial Crawford War Memorial Crawfordjohn War Memorial Crossford War Memorial Douglas War Memorial East Kilbride War Memorial Eisrickle Churchyard War Memorial Eisrickle War Memorial (Hope Cottage) Ferniegair War Memorial Forth War Memorial Hamilton War Memorial Hamilton Town House War Memorial Haywood War Memorial High Blantyre War Memorial Kirkfieldbank War Memorial Lanark War Memorial Larkhall War Memorial Law War Memorial Leadhills War Memorial Lesmahagow War Memorial Netherburn War Memorial New Lanark War Memorial Pettinain War Memorial Rutherglen War Memorial, Glasgow Road Rutherglen War Memorial, Mill Street Shepherd's Lane War Memorial Stonehouse War Memorial Strathaven War Memorial Symington War Memorial Uddingston War Memorial Westburn War Memorial Wiston War Memorial Ashgill War Memorial Rorison Church, Ashgill, near Larkhall 'In HONOURED Memory of The men of/his District Who died for their Country's sake In the Great War 1914 - 1918' Allan, J.S. Lieut. R.S.F. Bell, T, Sgt. Gordons Bickerstaff, W. Cpl. H.C.C. -

Tweed Local Plan District Local Flood Risk Management Plan INTERIM REPORT

Tweed Local Flood Risk Management Plan 2016-2022: INTERIM REPORT Flood Risk Management (Scotland) Act 2009: Tweed Local Plan District Local Flood Risk Management Plan INTERIM REPORT Published by: Scottish Borders Council Lead Local Authority Tweed Local Plan District 01 March 2019 In partnership with: Tweed Local Flood Risk Management Plan 2016-2022: INTERIM REPORT Publication date: 1 March 2019 Terms and conditions Ownership: All intellectual property rights of the INTERIM REPORT Local Flood Risk Management Plan are owned by Scottish Borders Council, SEPA or its licensors. The INTERIM REPORT Local Flood Risk Management Plan cannot be used for or related to any commercial, business or other income generating purpose or activity, nor by value added resellers. You must not copy, assign, transfer, distribute, modify, create derived products or reverse engineer the INTERIM REPORT Local Flood Risk Management Plan in any way except where previously agreed with Scottish Borders Council or SEPA. Your use of the INTERIM REPORT Local Flood Risk Management Plan must not be detrimental to Scottish Borders Council or SEPA or other responsible authority, its activities or the environment. Warranties and Indemnities: All reasonable effort has been made to ensure that the INTERIM REPORT Local Flood Risk Management Plan is accurate for its intended purpose, no warranty is given by Scottish Borders Council or SEPA in this regard. Whilst all reasonable effort has been made to ensure that the INTERIM REPORT Local Flood Risk Management Plan are up to date, complete and accurate at the time of publication, no guarantee is given in this regard and ultimate responsibility lies with you to validate any information given. -

Planning Performance Framework 2018 - 2019

Community and Enterprise Resources Planning and Economic Development South Lanarkshire Planning Performance Framework 2018-2019 Planning Performance Framework 2018 - 2019 Contents Chapter Page 1 Introduction : Background to Planning Performance Framework 3 The Planning Service in South Lanarkshire 4 2 Part 1 - Qualitative Narrative and Case Studies 6 3 Part 2 - Supporting evidence 41 4 Part 3 - Service improvements : Service improvements 2019/20 44 Delivery of Planning Service Improvement Actions 2018/19 45 5 Part 4 - South Lanarkshire Council - National Headline Indicators 47 6 Part 5 - South Lanarkshire Council - Official Statistics 52 7 Part 6 - South Lanarkshire Planning Service - Workforce information 55 Page 1 Planning Performance Framework 2018 - 2019 Chapter 1 Introduction Background to Planning The key work objectives of the service are set • Working with communities and partners Performance Framework out in the Council Plan - Connect. In terms of to promote high quality, thriving and their relevance to the planning service these sustainable communities; The Planning Performance Framework is the include:- • Supporting communities by tackling Council’s annual report on its planning service disadvantage and deprivation; and is used to highlight the activities and • Supporting the local economy by providing the right conditions for inclusive growth; • Improving the quality, access and achievements of the service over the last 12 availability of housing; months. The document will be submitted to the • Improving the quality of the physical Scottish Government who will provide feedback. environment; • Achieving the efficient and effective use of resources; In 2018 the service received ten green, three • Improving the road network, influencing amber and no red markers. improvements in public transport and • Promoting performance management and encouraging active travel; improvement; The planning system has a key role in helping • Embedding governance and accountability. -

Identification of Pressures and Impacts Arising Frm Strategic Development

Report for Scottish Environment Protection Agency/ Neil Deasley Planning and European Affairs Manager Scottish Natural Heritage Scottish Environment Protection Agency Erskine Court The Castle Business Park Identification of Pressures and Impacts Stirling FK9 4TR Arising From Strategic Development Proposed in National Planning Policy Main Contributors and Development Plans Andrew Smith John Pomfret Geoff Bodley Neil Thurston Final Report Anna Cohen Paul Salmon March 2004 Kate Grimsditch Entec UK Limited Issued by ……………………………………………… Andrew Smith Approved by ……………………………………………… John Pomfret Entec UK Limited 6/7 Newton Terrace Glasgow G3 7PJ Scotland Tel: +44 (0) 141 222 1200 Fax: +44 (0) 141 222 1210 Certificate No. FS 13881 Certificate No. EMS 69090 09330 h:\common\environmental current projects\09330 - sepa strategic planning study\c000\final report.doc In accordance with an environmentally responsible approach, this document is printed on recycled paper produced from 100% post-consumer waste or TCF (totally chlorine free) paper COMMISSIONED REPORT Summary Report No: Contractor : Entec UK Ltd BACKGROUND The work was commissioned jointly by SEPA and SNH. The project sought to identify potential pressures and impacts on Scottish Water bodies as a consequence of land use proposals within the current suite of Scottish development Plans and other published strategy documents. The report forms part of the background information being collected by SEPA for the River Basin Characterisation Report in relation to the Water Framework Directive. The project will assist SNH’s environmental audit work by providing an overview of trends in strategic development across Scotland. MAIN FINDINGS Development plans post 1998 were reviewed to ensure up-to-date and relevant information. -

Woodhead Farm Blackwood Estate • Lesmahagow • Lanark

WOODHEAD FARM BLACKWOOD ESTATE • LESMAHAGOW • LANARK SPACIOUS EARLY VICTORIAN FARMHOUSE WITH FLEXIBLE LAYOUT AND 2 ACRES OF GARDEN. WOODHEAD FARM BLACKWOOD ESTATE • LESMAHAGOW LANARK • ML11 0JG ENTRANCE HALL DRAWING ROOM / LIVING ROOM SITTING ROOM DINING ROOM CONSERVATORY 2 KITCHENS UTILITY ROOM OFFICE STUDIO BEDROOM WITH EN SUITE 3 FURTHER BEDROOMS FAMILY BATHROOM 2 SHOWER ROOMS LOFT ROOM / BEDROOM FLOORED ATTIC DOUBLE GARAGE TOOL STORE BYRE APPROX 2 ACRES Glasgow city centre: 23.5 miles Glasgow Airport: 30 miles Edinburgh Airport: 44 miles DIRECTIONS From Glasgow continue south on the M74 taking the Junction 9 exit and follow signs into Kirkmuirhill and Blackwood. Continue into the village of Blackwood and turn left onto Thornton Road (B7086) towards Strathaven. Continue onto Strathaven Road and beyond the village of Boghead take a right turn; Woodhead Farm is the first house on the right hand side. SITUATION Woodhead Farm sits in a picturesque semi rural location overlooking surrounding farmland, yet is conveniently placed for the towns of Lesmahagow, Strathaven and Hamilton. The farmhouse, which sits close to the village of Boghead, has beautiful open aspects. There is local primary schooling at Bent Primary School and secondary schooling at Blackwood. DESCRIPTION Occupying a peaceful semi rural position within the picturesque Blackwood estate, Woodhead Farm is an elegant, traditionally built detached farmhouse built circa 1840 which is surrounded by carefully maintained mature gardens which extend to approximately 2 acres. The property is surrounded by farmland and has beautiful open aspects. The accommodation within the farmhouse is all on one level and would be ideal for two separate families or multi generational living, as there are two separate entrances, two hallways and two kitchens. -

South Lanarkshire Landscape Capacity Study for Wind Energy

South Lanarkshire Landscape Capacity Study for Wind Energy Report by IronsideFarrar 7948 / February 2016 South Lanarkshire Council Landscape Capacity Study for Wind Energy __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS 3.3 Landscape Designations 11 3.3.1 National Designations 11 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Page No 3.3.2 Local and Regional Designations 11 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 3.4 Other Designations 12 1.1 Background 1 3.4.1 Natural Heritage designations 12 1.2 National and Local Policy 2 3.4.2 Historic and cultural designations 12 1.3 The Capacity Study 2 3.4.3 Tourism and recreational interests 12 1.4 Landscape Capacity and Cumulative Impacts 2 4.0 VISUAL BASELINE 13 2.0 CUMULATIVE IMPACT AND CAPACITY METHODOLOGY 3 4.1 Visual Receptors 13 2.1 Purpose of Methodology 3 4.2 Visibility Analysis 15 2.2 Study Stages 3 4.2.1 Settlements 15 2.3 Scope of Assessment 4 4.2.2 Routes 15 2.3.1 Area Covered 4 4.2.3 Viewpoints 15 2.3.2 Wind Energy Development Types 4 4.2.4 Analysis of Visibility 15 2.3.3 Use of Geographical Information Systems 4 5.0 WIND TURBINES IN THE STUDY AREA 17 2.4 Landscape and Visual Baseline 4 5.1 Turbine Numbers and Distribution 17 2.5 Method for Determining Landscape Sensitivity and Capacity 4 5.1.1 Operating and Consented Wind Turbines 17 2.6 Defining Landscape Change and Cumulative Capacity 5 5.1.2 Proposed Windfarms and Turbines (at March 2015) 18 2.6.1 Cumulative Change -

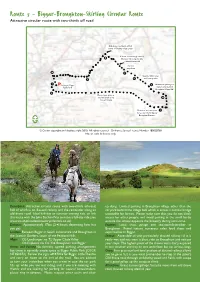

Biggar-Broughton-Skirling Circular Route Attractive Circular Route with Two-Thirds Off Road

Route 5 - Biggar-Broughton-Skirling Circular Route Attractive circular route with two-thirds off road Old drove road leads off NE corner of Skirling village green If drove road through trees is 8 blocked, ride along the side of the adjacent field Ford or jump burn 10 7 Beware rabbit holes 9 6 and loose ponies 1 PParking at Biggar 5 Alternative parking for Public Park trailers only behind Broughton Village Hall 2 Please leave gates as you find them along 4 disused railway Dismount and lead your 3 horse over the bridge by Broughton Brewery N © Crown copyright and database right 2010. All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence Number 100020730 Not to scale. Indicative only. Description: Attractive circular route with two-thirds off-road, up dung. Limited parking in Broughton village other than the half of which is on disused railway and the remainder along an car park behind the village hall, which is across a narrow bridge old drove road. Ideal half-day or summer evening ride, or link unsuitable for lorries. Please make sure that you do not block this route with the John Buchan Way to make a full-day ride (see access for other people, and avoid parking in the small lay-by www.southofscotlandcountrysidetrails.co.uk). outside the school opposite the brewery during term-time. Distance: Approximately 17km (2-4 hours, depending how fast Facilities: Local shop, garage and tea-room/bistro/bar in you go). Broughton. Petrol station, numerous cafes, food shops and Location: Between Biggar in South Lanarkshire and Broughton in supermarket in Biggar. -

For Sale Clyde Valley Caravan Park

FOR SALE CLYDE VALLEY CARAVAN PARK Guide Price £1.95m– Feuhold KIRKFIELDBANK, LANARK CLYDE VALLEY CARAVAN PARK, SYCAMORE GROVE, KIRKFIELDBANK, LANARK, ML11 9JW SUMMARY • Established mixed residential and holiday park extending in total to 12.8 acres (5.2 ha) including riverbed. • Site Licence for 65 residential, 50 holiday static and 75 tourers per hectare. • Developed with 59 residential pitches, (54 privately owned) 35 static caravan pitches (26 privately owned) and 45 touring caravan pitches with electric hook ups. • Fishing rights and owner’s twin park home included. • Guide Price £1.95m INTRODUCTION AND LOCATION In the area are a wide range of tourist attractions, including the world renowned New Lanark World Heritage Clyde Valley Caravan Park is a long established mixed Site, Lanark Racecourse and the Falls of Clyde Nature holiday and residential park with beautiful river frontage in Reserve. In addition, the area is excellently suited for a popular location. The park is developed with dedicated walkers and outdoor pursuits enthusiasts, with Blackhill static, touring and residential areas and includes a superb Viewpoint, Lanark heritage walks and Lanark Golf Club all opportunity for further pitch development under the within easy reach. existing permission. The park is easily accessed from the A72 tourist route The park has been in family ownership since 1970 and is through the popular Clyde Valley which connects Lanark to for sale due to retirement. Clyde Valley Caravan Park is theM74andGlasgow.ThecentreofGlasgowcanbe situated on the outskirts of the picturesque village of accessed within a 40 minute drive while Edinburgh is only Kirkfieldbank, only approximately one mile to the west of approximately one hour to the north east. -

South Lanarkshire Council – Scotland Date (August, 2010)

South Lanarkshire Council – Scotland Date (August, 2010) 2010 Air Quality Progress Report for South Lanarkshire Council In fulfillment of Part IV of the Environment Act 1995 Local Air Quality Management Date (August, 2010) Progress Report i Date (August, 2010) South Lanarkshire Council - Scotland ii Progress Report South Lanarkshire Council – Scotland Date (August, 2010) Local Ann Crossar Authority Officer Department Community Resources, Environmental Services Address 1st Floor Atholl House, East Kilbride, G74 1LU Telephone 01355 806509 e-mail [email protected]. uk Report G_SLC_006_Progress Report Reference number Date July 2010 Progress Report iii Date (August, 2010) South Lanarkshire Council - Scotland Executive Summary A review of new pollutant monitoring data and atmospheric emission sources within the South Lanarkshire Council area has been undertaken. The assessment compared the available monitoring data to national air quality standards in order to identify any existing exceedences of the standards. Data was gathered from various national and local sources with regard to atmospheric emissions from: road traffic; rail; aircraft; shipping; industrial processes; intensive farming operations; domestic properties; biomass plants; and dusty processes. The screening methods outlined in the technical guidance were used to determine the likelihood that a particular source would result in an exceedence of national air quality standards. The review of new and changed emission sources identified no sources that were likely to -

Headquarters, Strathclyde Regional Council, 20 India Street, Glasgow

312 THE EDINBURGH GAZETTE 3 MARCH 1987 NOTICE OF SUBMISSION OF ALTERATIONS Kyle & Carrick District Council, Headquarters, TO STRUCTURE PLAN Clydesdale District Council, Burns House, Headquarters, TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING (SCOTLAND) ACT 1972 Burns Statue Square, Council Offices, Ayr STRATHCLYDE STRUCTURE PLAN South Vennel, Lanark Monklands District Council, THE Strathclyde Regional Council submitted alterations to the above- Headquarters, named structure plan to the Secretary of State for Scotland on 18th Cumbernauld & Kilsyth District Municipal Buildings, February 1987 for his approval. Council, Coatbridge Headquarters, Certified copies of the alterations to the plan, of the report of the Council Offices, results of review of relevant matters and of the statement mentioned in Motherwell District Council, Bron Way, Section 8(4) of the Act have been deposited at the offices specified on the Headquarters, Cumbernauld Schedule hereto. Civic Centre, Motherwell The deposited documents are available for inspection free of charge Cumnock & Doon Valley District during normal office hours. Council, Renfrew District Council, Objections to the alterations to the structure plan should be sent in Headquarters, Headquarters, writing to the Secretary, Scottish Development Department, New St Council Offices, Municipal Buildings, Andrew's House, St James Centre, Edinburgh EH1 3SZ, before 6th Lugar, Cotton Street, April 1987. Objections should state the name and address of the Cumnock Paisley objector, the matters to which they relate, and the grounds on which they are made*. A person making objections may request to be notified Strathkelvin District Council, of the decision on the alterations to the plan. Headquarters, Council Chambers, * Forms for making objections are available at the places where Tom Johnston House, documents have been deposited. -

WAT IF? Woolfords, Auchengray and Tarbrax Improvement Foundation

WAT IF? Woolfords, Auchengray and Tarbrax Improvement Foundation Community Action Plan 2013 - 2018 A Scottish Charitable Incorporated Organisation Charity Number SC043606 May 2013 MAP OF TRUST’S OF AREA MAP This Community Action Plan, and the work of WAT IF?, covers the villages of Woolfords, Auchengray and Tarbrax and the settlements within a 3-mile radius of Stallashaw Moss. Ongoing review of the Community Action Plan 2013 to 2018 WAT IF? will be reviewing this Community Action Plan on an annual basis, and in the meantime the community will be regularly updated on the progress of the priorities and actions highlighted in this report. However, the priorities and actions will be progressed more quickly as members of the community become involved in setting up working groups. We look forward to hearing from you! WOOLFORDS, AUCHENGRAY AND TARBRAX IMPROVEMENT FOUNDATION 2 WAT IF? CONTENTS Map of Trust’s Area of Operation 2 Introduction 4 PART 1: INVOLVING THE COMMUNITY 1.1 Involvement Process 5 1.2 Our Community Now 6 Woolfords 7 Auchengray 7 Tarbrax 7 1.3 Our Community Consultation 8 1.4 Household Responses 8 1.5 Farm and Small Business Responses 8 1.6 Findings of Consultation 8 PART 2: COMMUNITY VISION 2.1 Our Vision - Our Future 9 2.2 A Sustainable Local Economy 9 2.3 Achieving a Sustainable Vision 9 PART 3: ACTION STRATEGIES - THE FUTURE Theme 1: Roads and Transport 10 Theme 2: Green Spaces and Heritage 11 Theme 3: Village Enhancement and Facilities 12 Theme 4: Community Activities 13 Theme 5: Services and Communications 14 COMMUNITY VISION FUTURE WAT IF? 3 This Community Action Plan covers the villages of Woolfords, Auchengray and Tarbrax and the settlements within a 3-mile radius of Stallashaw Moss, as designated on the map (page 2). -

Hand-Book of Hamilton, Bothwell, Blantyre, and Uddingston. with a Directory

; Hand-Book HAMILTON, BOTHWELL, BLANTYRE, UDDINGSTON W I rP H A DIE EJ C T O R Y. ILLUSTRATED BY SIX STEEL ENGRAVINGS AND A MAP. AMUS MACPHERSON, " Editor of the People's Centenary Edition of Burns. | until ton PRINTED AT THE "ADVERTISER" OFFICE, BY WM. NAISMITH. 1862. V-* 13EFERKING- to a recent Advertisement, -*-*; in which I assert that all my Black and Coloured Cloths are Woaded—or, in other wards, based with Indigo —a process which,, permanently prevents them from assuming that brownish appearance (daily apparent on the street) which they acquire after being for a time in use. As a guarantee for what I state, I pledge myself that every piece, before being taken into stock, is subjected to a severe chemical test, which in ten seconds sets the matter at rest. I have commenced the Clothing with the fullest conviction that "what is worth doing is worth doing well," to accomplish which I shall leave " no stone untamed" to render my Establishment as much a " household word " ' for Gentlemen's Clothing as it has become for the ' Unique Shirt." I do not for a moment deny that Woaded Cloths are kept by other respectable Clothiers ; but I give the double assurance that no other is kept in my stock—a pre- caution that will, I have no doubt, ultimately serve my purpose as much as it must serve that of my Customers. Nearly 30 years' experience as a Tradesman has convinced " me of the hollowness of the Cheap" outcry ; and I do believe that most people, who, in an incautious moment, have been led away by the delusive temptation of buying ' cheap, have been experimentally taught that ' Cheapness" is not Economy.