(Crustacea; Isopoda) in Freshwater

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anchialine Cave Biology in the Era of Speleogenomics Jorge L

International Journal of Speleology 45 (2) 149-170 Tampa, FL (USA) May 2016 Available online at scholarcommons.usf.edu/ijs International Journal of Speleology Off icial Journal of Union Internationale de Spéléologie Life in the Underworld: Anchialine cave biology in the era of speleogenomics Jorge L. Pérez-Moreno1*, Thomas M. Iliffe2, and Heather D. Bracken-Grissom1 1Department of Biological Sciences, Florida International University, Biscayne Bay Campus, North Miami FL 33181, USA 2Department of Marine Biology, Texas A&M University at Galveston, Galveston, TX 77553, USA Abstract: Anchialine caves contain haline bodies of water with underground connections to the ocean and limited exposure to open air. Despite being found on islands and peninsular coastlines around the world, the isolation of anchialine systems has facilitated the evolution of high levels of endemism among their inhabitants. The unique characteristics of anchialine caves and of their predominantly crustacean biodiversity nominate them as particularly interesting study subjects for evolutionary biology. However, there is presently a distinct scarcity of modern molecular methods being employed in the study of anchialine cave ecosystems. The use of current and emerging molecular techniques, e.g., next-generation sequencing (NGS), bestows an exceptional opportunity to answer a variety of long-standing questions pertaining to the realms of speciation, biogeography, population genetics, and evolution, as well as the emergence of extraordinary morphological and physiological adaptations to these unique environments. The integration of NGS methodologies with traditional taxonomic and ecological methods will help elucidate the unique characteristics and evolutionary history of anchialine cave fauna, and thus the significance of their conservation in face of current and future anthropogenic threats. -

Seasonal Diet Pattern of Non-Native Tubenose Goby (Proterorhinus Semilunaris) in a Lowland Reservoir (Mušov, Czech Republic)

Knowledge and Management of Aquatic Ecosystems (2010) 397, 02 http://www.kmae-journal.org c ONEMA, 2010 DOI: 10.1051/kmae/2010018 Seasonal diet pattern of non-native tubenose goby (Proterorhinus semilunaris) in a lowland reservoir (Mušov, Czech Republic) Z. Adámek(1),P.Jurajda(2),V.Prášek(2),I.Sukop(3) Received March 18, 2010 / Reçu le 18 mars 2010 Revised May 21, 2010 / Révisé le 21 mai 2010 Accepted June 3rd, 2010 / Accepté le 3 juin 2010 ABSTRACT Key-words: The tubenose goby (Proterorhinus semilunaris) is a gobiid species cur- Gobiidae, rently extending its area of distribution in Central Europe. The objective food, of the study was to evaluate the annual pattern of its feeding habits in lowland the newly colonised habitats of the Mušov reservoir on the Dyje River (the reservoir, Danube basin, Czech Republic) with respect to natural food resources. rip-rap bank, In the reservoir, tubenose goby has established a numerous population, the Dyje River densely colonising stony rip-rap banks. Its diet was exclusively of an- imal origin with significant dominance of and preference for two food items – chironomid (Chironomidae) larvae and waterlouse (Asellus aquati- cus), which contributed 40.2 and 27.6%, respectively, to the total food bulk ingested. The index of preponderance for the two items was also very high, amounting to 73.8 and 26.5, respectively. In the annual pat- tern, a remarkable preference for chironomid larvae was recorded in the summer period whilst waterlouse were consumed predominantly in win- ter months. The proportion of other food items was rather marginal – only corixids, copepods, ceratopogonids and cladocerans were of certain mi- nor importance with proportions of 5.4, 4.3, 4.1 and 3.9%, respectively. -

Global Diversity of Marine Isopods (Except Asellota and Crustacean Symbionts)

Collection Review Global Diversity of Marine Isopods (Except Asellota and Crustacean Symbionts) Gary C. B. Poore1*, Niel L. Bruce2,3 1 Museum Victoria, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 2 Museum of Tropical Queensland and School of Marine and Tropical Biology, James Cook University, Townsville, Queensland, Australia, 3 Department of Zoology, University of Johannesburg, Auckland Park, South Africa known from the supralittoral and intertidal to depths in excess of Abstract: The crustacean order Isopoda (excluding six kilometres. Isopods are a highly diverse group of crustaceans, Asellota, crustacean symbionts and freshwater taxa) with more than 10,300 species known to date, approximately comprise 3154 described marine species in 379 genera 6,250 of these being marine or estuarine. In the groups under in 37 families according to the WoRMS catalogue. The discussion here (about half the species) the vast majority of species history of taxonomic discovery over the last two centuries are known from depths of less than 1000 metres. is reviewed. Although a well defined order with the Peracarida, their relationship to other orders is not yet The Isopoda is one of the orders of peracarid crustaceans, that resolved but systematics of the major subordinal taxa is is, those that brood their young in a marsupium under the body. relatively well understood. Isopods range in size from less They are uniquely defined within Peracarida by the combination than 1 mm to Bathynomus giganteus at 365 mm long. of one pair of uropods attached to the pleotelson and pereopods of They inhabit all marine habitats down to 7280 m depth only one branch. Marine isopods are arguably the most but with few doubtful exceptions species have restricted morphologically diverse order of all the Crustacea. -

Changes in Species Composition of Haploniscidae (Crustacea Isopoda)

Progress in Oceanography 180 (2020) 102233 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Progress in Oceanography journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/pocean Changes in species composition of Haploniscidae (Crustacea: Isopoda) across T potential barriers to dispersal in the Northwest Pacific ⁎ Nele Johannsena,b, Lidia Linsa,b,c, Torben Riehla,b, Angelika Brandta,b, a Goethe University, Biosciences, Institute for Ecology, Evolution und Diversity, Max-von-Laue-Str. 13, 60438 Frankfurt am Main, Germany b Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum, Marine Zoology, Senckenberganlage 25, 60325 Frankfurt am Main, Germany c Ghent University, Marine Biology Research Group, Krijgslaan 281/S8, 9000 Ghent, Belgium ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Speciation processes as drivers of biodiversity in the deep sea are still not fully understood. One potential driver Hadal for species diversification might be allopatry caused by geographical barriers, such as ridges or trenches, or Ecology physiological barriers associated with depth. We analyzed biodiversity and biogeography of 21 morphospecies of Sea of Okhotsk the deep-sea isopod family Haploniscidae to investigate barrier effects to species dispersal in the Kuril- Deep sea Kamchatka Trench (KKT) area in the Northwest (NW) Pacific. Our study is based on 2652 specimens from three Abyssal genera, which were collected during the German-Russian KuramBio I (2012) and II (2016) expeditions as well as Isopoda Kuril Kamchatka Trench the Russian-German SokhoBio (2015) campaign. The sampling area covered two potential geographical barriers Distribution (the Kuril Island archipelago and the Kuril-Kamchatka Trench), as well as three depth zones (bathyal, abyssal, Northwest Pacific hadal). We found significant differences in relative species abundance between abyssal and hadal depths. -

Download Full Article in PDF Format

DIRECTEUR DE LA PUBLICATION / PUBLICATION DIRECTOR : Bruno David Président du Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle RÉDACTRICE EN CHEF / EDITOR-IN-CHIEF : Laure Desutter-Grandcolas ASSISTANTE DE RÉDACTION / ASSISTANT EDITOR : Anne Mabille ([email protected]) MISE EN PAGE / PAGE LAYOUT : Anne Mabille COMITÉ SCIENTIFIQUE / SCIENTIFIC BOARD : James Carpenter (AMNH, New York, États-Unis) Maria Marta Cigliano (Museo de La Plata, La Plata, Argentine) Henrik Enghoff (NHMD, Copenhague, Danemark) Rafael Marquez (CSIC, Madrid, Espagne) Peter Ng (University of Singapore) Jean-Yves Rasplus (INRA, Montferrier-sur-Lez, France) Jean-François Silvain (IRD, Gif-sur-Yvette, France) Wanda M. Weiner (Polish Academy of Sciences, Cracovie, Pologne) John Wenzel (The Ohio State University, Columbus, États-Unis) COUVERTURE / COVER : Akrophryxus milvus n. gen., n. sp., holotype female, MNHN-IU-2014-20314, attached to Ethusa machaera Castro, 2005, macropod images. Zoosystema est indexé dans / Zoosystema is indexed in: – Science Citation Index Expanded (SciSearch®) – ISI Alerting Services® – Current Contents® / Agriculture, Biology, and Environmental Sciences® – Scopus® Zoosystema est distribué en version électronique par / Zoosystema is distributed electronically by: – BioOne® (http://www.bioone.org) Les articles ainsi que les nouveautés nomenclaturales publiés dans Zoosystema sont référencés par / Articles and nomenclatural novelties published in Zoosystema are referenced by: – ZooBank® (http://zoobank.org) Zoosystema est une revue en flux continu publiée par les Publications scientifiques du Muséum, Paris / Zoosystema is a fast track journal published by the Museum Science Press, Paris Les Publications scientifiques du Muséum publient aussi / The Museum Science Press also publish: Adansonia, Geodiversitas, Anthropozoologica, European Journal of Taxonomy, Naturae, Cryptogamie sous-sections Algologie, Bryologie, Mycologie. Diffusion – Publications scientifiques Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle CP 41 – 57 rue Cuvier F-75231 Paris cedex 05 (France) Tél. -

The Coume Ouarnède System, a Hotspot of Subterranean Biodiversity in Pyrenees (France)

diversity Article The Coume Ouarnède System, a Hotspot of Subterranean Biodiversity in Pyrenees (France) Arnaud Faille 1,* and Louis Deharveng 2 1 Department of Entomology, State Museum of Natural History, 70191 Stuttgart, Germany 2 Institut de Systématique, Évolution, Biodiversité (ISYEB), UMR7205, CNRS, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Sorbonne Université, EPHE, 75005 Paris, France; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Located in Northern Pyrenees, in the Arbas massif, France, the system of the Coume Ouarnède, also known as Réseau Félix Trombe—Henne Morte, is the longest and the most complex cave system of France. The system, developed in massive Mesozoic limestone, has two distinct resur- gences. Despite relatively limited sampling, its subterranean fauna is rich, composed of a number of local endemics, terrestrial as well as aquatic, including two remarkable relictual species, Arbasus cae- cus (Simon, 1911) and Tritomurus falcifer Cassagnau, 1958. With 38 stygobiotic and troglobiotic species recorded so far, the Coume Ouarnède system is the second richest subterranean hotspot in France and the first one in Pyrenees. This species richness is, however, expected to increase because several taxonomic groups, like Ostracoda, as well as important subterranean habitats, like MSS (“Milieu Souterrain Superficiel”), have not been considered so far in inventories. Similar levels of subterranean biodiversity are expected to occur in less-sampled karsts of central and western Pyrenees. Keywords: troglobionts; stygobionts; cave fauna Citation: Faille, A.; Deharveng, L. The Coume Ouarnède System, a Hotspot of Subterranean Biodiversity in Pyrenees (France). Diversity 2021, 1. Introduction 13 , 419. https://doi.org/10.3390/ Stretching at the border between France and Spain, the Pyrenees are known as one d13090419 of the subterranean hotspots of the world [1]. -

Guide to Crustacea

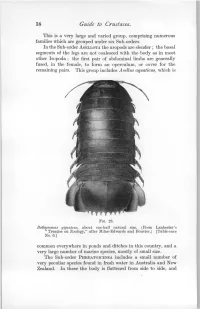

38 Guide to Crustacea. This is a very large and varied group, comprising numerous families which are grouped under six Sub-orders. In the Sub-order ASELLOTA the uropods are slender ; the basal segments of the legs are not coalesced with the body as in most other Isopoda ; the first pair of abdominal limbs are generally fused, in the female, to form an operculum, or cover for the remaining pairs. This group includes Asellus aquaticus, which is FIG. 23. Bathynomus giganteus, about one-half natural size. (From Lankester's "Treatise on Zoology," after Milne-Edwards and Bouvier.) [Table-case No. 6.] common everywhere in ponds and ditches in this country, and a very large number of marine species, mostly of small size. The Sub-order PHKEATOICIDEA includes a small number of very peculiar species found in fresh water in Australia and New Zealand. In these the body is flattened from side to side, and Peraca rida—Isopoda. 39 the animals in other respects have a superficial resemblance to Amphipoda. In the Sub-order FLABELLIFERA the terminal limbs of the abdomen (uropods) are spread out in a fan-like manner on each side of the telson. Many species of this group, belonging to the family Cymothoidae, are blood-sucking parasites of fish, and some of them are remarkable for being hermaphrodite (like the Cirri- pedia), each animal being at first a male and afterwards a female. Mo' of these parasites are found adhering to the surface of the body, behind the fins or under the gill-covers of the fish. A few, however, become internal parasites like the Artystone trysibia exhibited in this case, which has burrowed into the body of a Brazilian freshwater fish. -

The 17Th International Colloquium on Amphipoda

Biodiversity Journal, 2017, 8 (2): 391–394 MONOGRAPH The 17th International Colloquium on Amphipoda Sabrina Lo Brutto1,2,*, Eugenia Schimmenti1 & Davide Iaciofano1 1Dept. STEBICEF, Section of Animal Biology, via Archirafi 18, Palermo, University of Palermo, Italy 2Museum of Zoology “Doderlein”, SIMUA, via Archirafi 16, University of Palermo, Italy *Corresponding author, email: [email protected] th th ABSTRACT The 17 International Colloquium on Amphipoda (17 ICA) has been organized by the University of Palermo (Sicily, Italy), and took place in Trapani, 4-7 September 2017. All the contributions have been published in the present monograph and include a wide range of topics. KEY WORDS International Colloquium on Amphipoda; ICA; Amphipoda. Received 30.04.2017; accepted 31.05.2017; printed 30.06.2017 Proceedings of the 17th International Colloquium on Amphipoda (17th ICA), September 4th-7th 2017, Trapani (Italy) The first International Colloquium on Amphi- Poland, Turkey, Norway, Brazil and Canada within poda was held in Verona in 1969, as a simple meet- the Scientific Committee: ing of specialists interested in the Systematics of Sabrina Lo Brutto (Coordinator) - University of Gammarus and Niphargus. Palermo, Italy Now, after 48 years, the Colloquium reached the Elvira De Matthaeis - University La Sapienza, 17th edition, held at the “Polo Territoriale della Italy Provincia di Trapani”, a site of the University of Felicita Scapini - University of Firenze, Italy Palermo, in Italy; and for the second time in Sicily Alberto Ugolini - University of Firenze, Italy (Lo Brutto et al., 2013). Maria Beatrice Scipione - Stazione Zoologica The Organizing and Scientific Committees were Anton Dohrn, Italy composed by people from different countries. -

Natur Und Heimat

Natur u. Heimat, 37. Jahrg., Heft 3, 1977 (1968): Gehäuse von Insekten-Larven, insbesondere von Chironomiden, in quar tären Sedimenten. Mitt. Geol. Inst. Univers. Hannover, 8, 34-53. ___.:._ HrLTERMANN, H. (1975): Kleiner Führer durch Solbad Laer T. W. Suderberger Hefte 1. - HrL TERMANN, H . (1976): Ein vergessener mittelalterlicher Baustein. Jb. Heimatbund Osnabrück-Land, 54-59. - HrLTERMANN, H. & K. MÄDLER (1977): Charophyten als palökologische Indikatoren und ihr Vorkommen in den Sinterkalken von Bad Laer T. W. Paläontol. Z. (im Druck). - ZEISSLER, H. (1977): Konchylien aus dem holozänen Travertin von Bad Laer, Kreis Osnabrück. (im Druck). Anschrift des Verfassers1: Prof. Dr. H. Hiltermann, Milanring 11, D-4518 Bad Laer. Die ersten Nachweise der Wasserassel Proasellus meridianus CRacovitza, 1919) (Crustacea, Isopoda Asellidae) im Einzugsgebiet der Ems KARL FRIEDRICH HERHAUS, Münster In Deutschland ist die von HENRY und MAGNIEZ (1970) revidierte Familie Asellida,e Sars, 1899, mit drei oberirdischen Arten vertreten. Die am weitesten verbreitete Art ist Asellus ( Asellus) aquaticus (L., 175 8); sie ist ein sibirisches Faunenelement, das sich postglazial nach Westen hin ausgebreitet hat (BrRSTEIN 1951; WILLIAMS 1962). Weitaus weniger häufig tritt die zweite Art, Proasellus coxalis (Dollfus, 1892), auf; diese im übrigen circummediterran verbreitete Art ist in Mittel europa mit der Unterart septentrionalis (Herbst, 1956) vertreten, die vermutlich erst in jüngster Zeit eingeschleppt worden ist (HERHAUS 1977). Am seltensten ist auf deutschem Boden die dritte Art, Proasellus meridianus (Racovitza, 1919). P. meridianus ist eine autochthon west europä,isch-atlantische Form (GRUNER 1965); in Deutschland wurde sie von STAMMER (1932) am linken Niederrhein nachgewiesen. Für die sichere Bestimmung der drei Arten ist die Untersuchung der Pleopoden II unter dem Binokular unerläßlich. -

(Janiridae, Isopoda, Crustacea), a Second Species of Austrofilius in the Mediterranean Sea, with a Discussion on the Evolutionary Biogeography of the Genus J

Austrofilius MAJORICENSIS SP. NOV. (JANIRIDAE, ISOPODA, CRUSTACEA), A SECOND SPECIES OF AUSTROFILIUS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA, WITH A DISCUSSION ON THE EVOLUTIONARY BIOGEOGRAPHY OF THE GENUS J. Castelló To cite this version: J. Castelló. Austrofilius MAJORICENSIS SP. NOV. (JANIRIDAE, ISOPODA, CRUSTACEA), A SECOND SPECIES OF AUSTROFILIUS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA, WITH A DISCUS- SION ON THE EVOLUTIONARY BIOGEOGRAPHY OF THE GENUS. Vie et Milieu / Life & Environment, Observatoire Océanologique - Laboratoire Arago, 2008, pp.193-201. hal-03246157 HAL Id: hal-03246157 https://hal.sorbonne-universite.fr/hal-03246157 Submitted on 2 Jun 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. VIE ET MILIEU - LIFE AND ENVIRONMENT, 2008, 58 (3/4): 193-201 AUSTROFILIUS MAJORICENSIS SP. NOV. (JANIRIDAE, ISOPODA, CRUSTACEA), A SECOND SPECIES OF AUSTROFILIUS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA, WITH A DISCUSSION ON THE EVOLUTIONARY BIOGEOGRAPHY OF THE GENUS J. CASTELLÓ Departament de Didàctica de les Ciències Experimentals i de la Matemàtica, Universitat de Barcelona, Passeig de la Vall d’Hebron 171, 08035 Barcelona, Spain [email protected] ISOPODA Abstract. – A new species of Janiroidean isopod, Austrofilius majoricensis sp. nov., from ASELLOTA JANIRIDAE Majorca (Balearic Islands, Western Mediterranean), is described. -

A Synopsis of the Biology and Life History of Ruffe

J. Great Lakes Res. 24(2): 170-1 85 Internat. Assoc. Great Lakes Res., 1998 A Synopsis of the Biology and Life History of Ruffe Derek H. Ogle* Northland College Mathematics Department Ashland, Wisconsin 54806 ABSTRACT. The ruffe (Gymnocephalus cernuus), a Percid native to Europe and Asia, has recently been introduced in North America and new areas of Europe. A synopsis of the biology and life history of ruffe suggests a great deal of variability exists in these traits. Morphological characters vary across large geographical scales, within certain water bodies, and between sexes. Ruffe can tolerate a wide variety of conditions including fresh and brackish waters, lacustrine and lotic systems, depths of 0.25 to 85 m, montane and submontane areas, and oligotrophic to eutrophic waters. Age and size at maturity dif- fer according to temperature and levels of mortality. Ruffe spawn on a variety ofsubstrates, for extended periods of time. In some populations, individual ruffe may spawn more than once per year. Growth of ruffe is affected by sex, morphotype, water type, intraspecific density, and food supply. Ruffe feed on a wide variety of foods, although adult ruffe feed predominantly on chironomid larvae. Interactions (i.e., competition and predation) with other species appear to vary considerably between system. INDEX WORDS: Ruffe, review, taxonomy, reproduction, diet, parasite, predation. INTRODUCTION DISTRIBUTION This is a review of the existing literature on Ruffe are native to all of Europe except for along ruffe, providing a synopsis of its biology and life the Mediterranean Sea, western France, Spain, Por- history. A review of the existing literature is tugal, Norway, northern Finland, Ireland, and Scot- needed at this time because the ruffe, which is na- land (Collette and Banarescu 1977, Lelek 1987). -

OREGON ESTUARINE INVERTEBRATES an Illustrated Guide to the Common and Important Invertebrate Animals

OREGON ESTUARINE INVERTEBRATES An Illustrated Guide to the Common and Important Invertebrate Animals By Paul Rudy, Jr. Lynn Hay Rudy Oregon Institute of Marine Biology University of Oregon Charleston, Oregon 97420 Contract No. 79-111 Project Officer Jay F. Watson U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 500 N.E. Multnomah Street Portland, Oregon 97232 Performed for National Coastal Ecosystems Team Office of Biological Services Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. Department of Interior Washington, D.C. 20240 Table of Contents Introduction CNIDARIA Hydrozoa Aequorea aequorea ................................................................ 6 Obelia longissima .................................................................. 8 Polyorchis penicillatus 10 Tubularia crocea ................................................................. 12 Anthozoa Anthopleura artemisia ................................. 14 Anthopleura elegantissima .................................................. 16 Haliplanella luciae .................................................................. 18 Nematostella vectensis ......................................................... 20 Metridium senile .................................................................... 22 NEMERTEA Amphiporus imparispinosus ................................................ 24 Carinoma mutabilis ................................................................ 26 Cerebratulus californiensis .................................................. 28 Lineus ruber .........................................................................