How Do You Translate a Text That Is Not a Text? How Do You Perform a Score That Is Not a Score?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Choreography for the Camera AB

Course Title CHOREOGRAPHY FOR THE CAMERA A/B Course CHORFORCAMER A/B Abbreviation Course Code 190121/22 Number Special Notes Year course. Prerequisite: 1 semester of any dance composition class, and 1 semester of any dance technique class. Prerequisite can be waived based-on comparable experience. Course This course provides a practical and theoretical introduction to dance for the camera, Description including choreography, video production and post-production as pertains to this genre of experimental filmmaking. To become familiar with the form, students will watch, read about, and discuss seminal dance films. Through studio-based exercises, viewings and discussions, we will consider specific approaches to translating, contextualizing, framing, and structuring movement in the cinematic format. Choreographic practices will be considered and practiced in terms of the spatial, temporal and geographic alternatives that cinema offers dance – i.e. a three-dimensional, and sculptural presentation of the body as opposed to the proscenium theatre. We will practice effectively shooting dance with video cameras, including basic camera functions, and framing, as well as employing techniques for play on gravity, continuity of movement and other body-focused approaches. The basics of non-linear editing will be taught alongside the craft of editing. Students will fulfill hands-on assignments imparting specific techniques. For mid-year and final projects, students will cut together short dance film pieces that they have developed through the various phases of the course. Students will have the option to work independently, or in teams on each of the assignments. At the completion of the course, students should have an informed understanding of the issues involved with translating the live form of dance into a screen art. -

Embodied History in Ralph Lemon's Come Home Charley Patton

“My Body as a Memory Map:” Embodied History in Ralph Lemon’s Come Home Charley Patton Doria E. Charlson I begin with the body, no way around it. The body as place, memory, culture, and as a vehicle for a cultural language. And so of course I’m in a current state of the wonderment of the politics of form. That I can feel both emotional outrageousness with my body as a memory map, an emotional geography of a particular American identity...1 Choreographer and visual artist Ralph Lemon’s interventions into the themes of race, art, identity, and history are a hallmark of his almost four-decade- long career as a performer and art-maker. Lemon, a native of Minnesota, was a student of dance and theater who began his career in New York, performing with multimedia artists such as Meredith Monk before starting his own company in 1985. Lemon’s artistic style is intermedial and draws on the visual, aural, musical, and physical to explore themes related to his personal history. Geography, Lemon’s trilogy of dance and intermedial artistic pieces, spans ten years of global, investigative creative processes aimed at unearthing the relationships among—and the possible representations of—race, art, identity, and history. Part one of the trilogy, also called Geography, premiered in 1997 as a dance piece and was inspired by Lemon’s journey to Africa, in particular to Côte d'Ivoire and Guinea, where Lemon sought to more deeply understand his identity as an African-American male artist. He subseQuently published a collection of writings, drawings, and notes which he had amassed during his research and travel in Africa under the title Geography: Art, Race, Exile. -

(The Efflorescence Of) Walter, an Exhibition by Ralph Lemon

Press Contact: Rachael Dorsey tel: 212 255-5793 ext. 14 fax: 212 645-4258 [email protected] For Immediate Release The Kitchen presents (The efflorescence of) Walter, an exhibition by Ralph Lemon New York, NY, April 17, 2007 – The Kitchen is pleased to present the first New York solo exhibition by choreographer, dancer, and visual artist Ralph Lemon. Titled (The efflorescence of) Walter, the show includes a body of work focused on the American South, featuring works-on-paper, a multiple-channel video installation, and other sculptural elements that explore history, memory, and memorialization. There will be an opening reception for the exhibition at The Kitchen (512 West 19th Street) on Friday, May 11 from 6- 8pm. Curated by Claire Tancons and Anthony Allen, the exhibition will be on view from May 11 – June 23, 2007. The Kitchen’s gallery hours are Tuesday-Friday, 12 to 6pm and Saturday, 11am to 6pm. Admission is Free. (The efflorescence of) Walter revolves around Lemon's collaborative relationship with Walter Carter, an African American man who has lived for almost a century in Yazoo City, Mississippi. Since 2002, Lemon and Carter have met twice a year and created a “collaborative meta-theater” in which actions scripted by Lemon are translated and transformed through Carter’s performance and improvisations. The exhibition weaves together videos of Walter’s actions with paintings, drawings and photographs by Lemon. Bringing together figures as varied as writer James Baldwin, artist Joseph Beuys, and Br’er Rabbit, a central character of African American folktales; as well as historical events from the Civil Rights era and cultural artifacts of the American South, this complex engagement with history, myth, and daily human existence explores how past, present, and future co-exist and at times collide. -

Pentacle-40Th-Ann.-Gala-Program.Pdf

40 Table of Contents Welcome What is the landscape for emerging artists? Thoughts from the Founding Director Past & Current Pentacle Artists Tribute to Past Pentacle Staff Board of Directors- Celebration Committee- Staff Body Wisdom: Pentacle Celebrates Forty Years Tonight’s Program & Performers Event Sponsors & Donors Greetings Welcome Thank you for joining us tonight and celebrating this 40th Anniversary! In 1976 we opened our doors with a staff of four, providing what we called “cluster management” to four companies. Our mission was then and remains today to help artists do what they do best….create works of art. We have steadfastlyprovided day-to-day administration services as well as local and national innovative projects to individual artists, companies and the broader arts community. But we did not and could not do it alone. We have had the support of literally hundreds of arts administrators, presenters, publicists, funders, and individual supporters. So tonight is a celebration of Pentacle, yes, and also a celebration of our enormously eclectic community. We want to thank all of the artists who have donated their time and energies to present their work tonight, the Rubin Museum for providing such a beautiful space, and all of you for joining us and supporting Pentacle. Welcome and enjoy the festivities! Mara Greenberg Patty Bryan Director Board Chair Thoughts from the Founding Director What is the landscape for emerging dance artists? A question addressed forty years later. There are many kinds of dance companies—repertory troupes that celebrate the dances of a country or re- gion, exquisitely trained ensembles that spotlight a particular idiom or form—classical ballet or Flamenco or Bharatanatyam, among other classicisms, and avocational troupes of a hundred sorts that proudly share the dances, often traditional, of a hundred different cultures. -

Talking Black Dance: Inside Out

CONVERSATIONS ACROSS THE FIELD OF DANCE STUDIES Talking Black Dance: Inside Out OutsideSociety of Dance InHistory Scholars 2016 | Volume XXXVI Table of Contents A Word from the Guest Editors ................................................4 The Mis-Education of the Global Hip-Hop Community: Reflections of Two Dance Teachers: Teaching and In Conversation with Duane Lee Holland | Learning Baakasimba Dance- In and Out of Africa | Tanya Calamoneri.............................................................................42 Jill Pribyl & Ibanda Grace Flavia.......................................................86 TALKING BLACK DANCE: INSIDE OUT .................6 Mackenson Israel Blanchard on Hip-Hop Dance Choreographing the Individual: Andréya Ouamba’s Talking Black Dance | in Haiti | Mario LaMothe ...............................................................46 Contemporary (African) Dance Approach | Thomas F. DeFrantz & Takiyah Nur Amin ...........................................8 “Recipe for Elevation” | Dionne C. Griffiths ..............................52 Amy Swanson...................................................................................93 Legacy, Evolution and Transcendence When Dance Voices Protest | Dancing Dakar, 2011-2013 | Keith Hennessy ..........................98 In “The Magic of Katherine Dunham” | Gregory King and Ellen Chenoweth .................................................53 Whiteness Revisited: Reflections of a White Mother | Joshua Legg & April Berry ................................................................12 -

Art Works Grants

National Endowment for the Arts — December 2014 Grant Announcement Art Works grants Discipline/Field Listings Project details are as of November 24, 2014. For the most up to date project information, please use the NEA's online grant search system. Art Works grants supports the creation of art that meets the highest standards of excellence, public engagement with diverse and excellent art, lifelong learning in the arts, and the strengthening of communities through the arts. Click the discipline/field below to jump to that area of the document. Artist Communities Arts Education Dance Folk & Traditional Arts Literature Local Arts Agencies Media Arts Museums Music Opera Presenting & Multidisciplinary Works Theater & Musical Theater Visual Arts Some details of the projects listed are subject to change, contingent upon prior Arts Endowment approval. Page 1 of 168 Artist Communities Number of Grants: 35 Total Dollar Amount: $645,000 18th Street Arts Complex (aka 18th Street Arts Center) $10,000 Santa Monica, CA To support artist residencies and related activities. Artists residing at the main gallery will be given 24-hour access to the space and a stipend. Structured as both a residency and an exhibition, the works created will be on view to the public alongside narratives about the artists' creative process. Alliance of Artists Communities $40,000 Providence, RI To support research, convenings, and trainings about the field of artist communities. Priority research areas will include social change residencies, international exchanges, and the intersections of art and science. Cohort groups (teams addressing similar concerns co-chaired by at least two residency directors) will focus on best practices and develop content for trainings and workshops. -

Mission Issue

free The San Francisco Arts Quarterly A Free Publication Dedicated to the SArtistic CommunityFAQ i 3 MISSION ISSUE - Bay Area Arts Calendar Oct. Nov. Dec. Jan - Southern Exposure - Galeria de la Raza - Ratio 3 Gallery - Hamburger Eyes - Oakland Museum - Headlands - Art Practical 6)$,B6)B$UWVB4XDUWHUO\BILQDOLQGG 30 Saturday October 16, 1-6pm Visit www.yerbabuena.org/gallerywalk for more details 111 Minna Gallery Chandler Fine Art SF Camerawork 111 Minna Street - 415/974-1719 170 Minna Street - 415/546-1113 657 Mission Street, 2nd Floor- www.111minnagallery.com www.chandlersf.com 415/512-2020 12 Gallagher Lane Crown Point Press www.sfcamerawork.org 12 Gallagher Lane - 415/896-5700 20 Hawthorne Street - 415/974-6273 UC Berkeley Extension www.12gallagherlane.com www.crownpoint.com 95 3rd Street - 415/284-1081 871 Fine Arts Fivepoints Arthouse www.extension.berkeley.edu/art/gallery.html 20 Hawthorne Street, Lower Level - 72 Tehama Street - 415/989-1166 Visual Aid 415/543-5155 fivepointsarthouse.com 57 Post Street, Suite 905 - 415/777-8242 www.artbook.com/871store Modernism www.visualaid.org The Artists Alley 685 Market Street- 415/541-0461 PAK Gallery 863 Mission Street - 415/522-2440 www.modernisminc.com 425 Second Street , Suite 250 - 818/203-8765 www.theartistsalley.com RayKo Photo Center www.pakink.com Catherine Clark Gallery 428 3rd Street - 415/495-3773 150 Minna Street - 415/399-1439 raykophoto.com www.cclarkgallery.com Galleries are open throughout the year. Yerba Buena Gallery Walks occur twice a year and fall. The Yerba Buena Alliance supports the Yerba Buena Nieghborhood by strengthening partnerships, providing critical neighborhood-wide leadership and infrastructure, serving as an information source and forum for the area’s diverse residents, businesses, and visitiors, and promoting the area as a destination. -

Ralph Lemon How Can You Stay in the House All Day and Not Go Anywhere? NOV 18 - 21 , 2010 Running Time 85 Minutes I

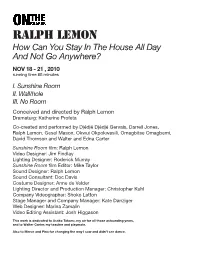

Ralph Lemon How Can You Stay In The House All Day And Not Go Anywhere? NOV 18 - 21 , 2010 running time 85 minutes I. Sunshine Room II. Wall/hole III. No Room Conceived and directed by Ralph Lemon Dramaturg: Katherine Profeta Co-created and performed by Djédjé Djédjé Gervais, Darrell Jones, Ralph Lemon, Gesel Mason, Okwui Okpokwasili, Omagbitse Omagbemi, David Thomson and Walter and Edna Carter Sunshine Room film: Ralph Lemon Video Designer: Jim Findlay Lighting Designer: Roderick Murray Sunshine Room film Editor: Mike Taylor Sound Designer: Ralph Lemon Sound Consultant: Doc Davis Costume Designer: Anne de Velder Lighting Director and Production Manager: Christopher Kuhl Company Videographer: Shoko Letton Stage Manager and Company Manager: Kate Danziger Web Designer: Marina Zamalin Video Editing Assistant: Josh Higgason This work is dedicated to Asako Takami, my air for all those astounding years, and to Walter Carter, my teacher and playmate. Also to Merce and Pina for changing the way I saw and didn’t see dance. How Can You Stay In The House All Day And Not Go Anywhere? is co-produced by Cross Performance, Inc. and MAPP International Productions. How Can You Stay received funding support from The MAP Fund, a program of Creative Capital supported by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation; The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts; the National Endowment for the Arts; the National Dance Project of the New England Foundation for the Arts (with lead funding from Doris Duke Charitable Foundation and additional funding from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Ford Foundation, and the Community Connections Fund of the MetLife Foundation); The Andrew W. -

1982 Danspace Project Presents Parallels with Blondell Cummings

1982 Danspace Project presents Parallels with Blondell Cummings, Fred Holland, Rrata Christine Jones, Ishmael Houston- Jones, Ralph Lemon, Bebe Miller, Harry Sheppard and Gus Solomons jr. 1987 The American Center in Paris, Dance Umbrella in London and Salle Patino in Geneva present Parallels in Black with Blondell Cummings, Fred Holland, Ishmael Houston-Jones, Ralph Lemon, Bebe Miller and Jawole Willa Jo Zollar. 2012 Danspace Project presents PLATFORM 2012: Parallels with Kyle Abraham, niv Acosta, Laylah Ali, Souleymane Badolo, Kevin Beasley, Hunter Carter, Nora Chipaumire, Blondell Cummings, Thomas F. DeFrantz, Marjani A. Forté, James Hannaham, Fred Holland, Ishmael Houston-Jones, Pedro Jiménez, Darrell Jones, Niall Noel Jones, Young Jean Lee, Nicholas Leichter, Ralph Lemon, Isabel Lewis, Gesel Mason, April Matthis, Bebe Miller, Dean Moss, Wangechi Mutu, Okwui Okpokwasili, Cynthia Oliver, Omagbitse Omagbemi, Will Rawls, Regina Rocke, Gus Solomons jr., Samantha Speis, Stacy Spence, David Thomson, Nari Ward, Marýa Wethers, Reggie Wilson, Ann Liv Young and Jawole Willa Jo Zollar. Danspace Project St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery 131 East 10th Street New York, NY 10003 danspaceproject.org Editor-in-Chief JUDY HUSSIE-TAYLOR Chief Curator ISHMAEL HOUSTON-JONES Managing Editor / Curatorial Fellow LYDIA BELL Photographer-in-Residence IAN DOUGLAS Writer-in-Residence CARL PARIS Printer DIGITAL COLOR CONCEPTS Designer JUDITH WALKER Publisher DANSPACE PROJECT PLATFORM 2012 DANSPACE PROJECT Contributing Writers THULANI DAVIS THOMAS F. DEFRANTZ JUDY HUSSIE-TAYLOR ISHMAEL HOUSTON-JONES RALPH LEMON BEBE MILLER DEAN MOSS WENDY PERRON HENRY PILLSBURY WILL RAWLS GUS SOLOMONS JR. BARBARA WATSON JAWOLE WILLA JO ZOLLAR Kyle Abraham niv Acosta Laylah Ali Souleymane Badolo Kevin Beasley Hunter Carter Nora Chipaumire Blondell Cummings Thomas F. -

Dancing Platform Praying Grounds

DANCING PLATFORM PRAYING GROUNDS: BLACKNESS, CHURCHES, AND DOWNTOWN DANCE DANCING PLATFORM PRAYING GROUNDS: BLACKNESS, DANCING DANSPACE PROJECT PLATFORM PLATFORM PRAYING GROUNDS: BLACKNESS, CHURCHES, AND DOWN- Danspace Project Platform TOWN DANCE ISBN 978-0-9700313-8-9 Since 2010, Danspace Project has published catalogues as part of its series of artist-curat- ed Platforms. Initiated by Danspace Project Executive Director and Chief Curator Judy 90000> Hussie-Taylor, the Platforms, "exhibitions that unfold over time," contextualize contem- porary dance and performance practices and histories. The 12th edition, Dancing Plat- form Praying Grounds: Blackness, Churches, and Downtown Dance, is edited by Reggie Wilson, Lydia Bell, and Kristin Juarez. Contributors include: Lauren Bakst, Lydia Bell, Thomas F. DeFrantz, Stephen Facey, Keely Garfield, Judy Hussie-Taylor, Darrell Jones, Prithi Kanakamedala, Kelly Kivland, Cynthia Oliver, Susan Osberg, Carl Paris, Julian Rose, Same As Sister (Hilary Brown and Briana Brown-Tipley), Radhika Subramaniam, 9 780970 031389 Kamau Ware, Ni’Ja Whitson, Tara Aisha Willis, Mabel O. Wilson, and Reggie Wilson. DANSPACE PROJECT PLATFORM DANCING PLATFORM PRAYING GROUNDS: BLACKNESS, CHURCHES, AND DOWN- TOWN DANCE Published by Danspace Project, New York, BOARD OF DIRECTORS on the occasion of Dancing Platform Praying Grounds: Blackness, Churches, and Down- President town Dance, curated by Reggie Wilson as Helen Warwick part of the Platform series at Danspace Project First Vice President Sam Miller First edition ©2018 Danspace Project Treasurer All rights reserved under pan-American copy- Sarah Needham right conventions. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or Secretary by any means without permission in writing David Parker from the publisher. -

Dormeshia Receives the 2021 Jacob's Pillow Dance Award

NATIONAL MEDAL OF ARTS | NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK FOR MORE INFORMATION AND PHOTOS CONTACT: Elise Linscott, Public Relations & Communications Coordinator [email protected] DORMESHIA RECEIVES THE 2021 JACOB’S PILLOW DANCE AWARD DORMESHIA HONORED AT GLOBAL PILLOW: A VIRTUAL GALA SUPPORTING JACOB’S PILLOW, JUNE 12 AT 7 P.M. June 8, 2021 (BECKET, Mass.)—Jacob’s Pillow announces Dormeshia as the recipient of the 2021 Jacob’s Pillow Dance Award. The Award, presented each year to an artist of exceptional vision and achievement, carries a cash prize of $25,000 which the artist can use in any way they wish. Dormeshia is a dynamic tap dancer, choreographer, and instructor who has been lauded as the best of her generation, both by her peers and esteemed dance critics. Her performances have appeared on the Broadway stage, in films, and in choreography for artists including Savion Glover and Gregory Hines. Dormeshia will be honored at Global Pillow: A Virtual Gala, which will be streamed free online on June 12 at 7 p.m. ET. “Dormeshia is quite simply one of the greatest tap dancers of our time,” said Jacob's Pillow Artistic & Executive Director Pamela Tatge. “She began by dancing with the greats when she was quite young and emerged with dazzling skill and artistry that is all her own. Dormeshia has made singular contributions to the tap world as performer, choreographer, collaborator, educator and mentor. She is a radiant human being whose elegance, flair and generosity of spirit draws us to new heights of what’s possible in the tap form. -

FOR MORE INFORMATION and PHOTOS CONTACT: Chelsea Wells, Jacob’S Pillow Public Relations Manager 413.243.9919 X132 [email protected]

FOR MORE INFORMATION AND PHOTOS CONTACT: Chelsea Wells, Jacob’s Pillow Public Relations Manager 413.243.9919 x132 [email protected] -or- Jodi Joseph, MASS MoCA Director of Communications 413.664.4481 x113 [email protected] JACOB’S PILLOW DANCE AND MASS MoCA CO-PRESENT BILL T. JONES AND OKWUI OKPOKWASILI IN RESPONSE TO NICK CAVE’S UNTIL MARCH 4 AND APRIL 7 AT MASS MoCA January 30, 2017 – (North Adams, MA) Cultural partners Jacob’s Pillow Dance and MASS MoCA present two solo works created in response to and performed within Nick Cave’s monumental exhibition Until, currently installed in MASS MoCA’s largest gallery. Iconic choreographer and Jacob’s Pillow Dance Award recipient Bill T. Jones will perform on March 4 at 8pm; choreographer, writer, actress, and New York Dance and Performance (―Bessie‖) Award recipient Okwui Okpokwasili will perform on April 7 at 8pm. Co-presentations by Jacob’s Pillow Dance and MASS MoCA are made possible by the Irene Hunter Fund for Dance. ―When I first heard about Nick Cave taking over Building 5 with Until, I immediately thought of Bill and what it would be like to have him perform in that world,‖ says Jacob’s Pillow Director Pamela Tatge. ―I’m also excited to introduce Berkshire audiences to Okwui Okpokwasili, and her stunning movement and text-based work. Both of these artists will give us singular perspectives on the issues raised in this groundbreaking exhibition.‖ ―Nick and Bill T. have been speaking for years about finding a way to work together,‖ remarks MASS MoCA Curator Denise Markonish.