1982 Danspace Project Presents Parallels with Blondell Cummings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Choreography for the Camera AB

Course Title CHOREOGRAPHY FOR THE CAMERA A/B Course CHORFORCAMER A/B Abbreviation Course Code 190121/22 Number Special Notes Year course. Prerequisite: 1 semester of any dance composition class, and 1 semester of any dance technique class. Prerequisite can be waived based-on comparable experience. Course This course provides a practical and theoretical introduction to dance for the camera, Description including choreography, video production and post-production as pertains to this genre of experimental filmmaking. To become familiar with the form, students will watch, read about, and discuss seminal dance films. Through studio-based exercises, viewings and discussions, we will consider specific approaches to translating, contextualizing, framing, and structuring movement in the cinematic format. Choreographic practices will be considered and practiced in terms of the spatial, temporal and geographic alternatives that cinema offers dance – i.e. a three-dimensional, and sculptural presentation of the body as opposed to the proscenium theatre. We will practice effectively shooting dance with video cameras, including basic camera functions, and framing, as well as employing techniques for play on gravity, continuity of movement and other body-focused approaches. The basics of non-linear editing will be taught alongside the craft of editing. Students will fulfill hands-on assignments imparting specific techniques. For mid-year and final projects, students will cut together short dance film pieces that they have developed through the various phases of the course. Students will have the option to work independently, or in teams on each of the assignments. At the completion of the course, students should have an informed understanding of the issues involved with translating the live form of dance into a screen art. -

Paul Taylor Dance Company’S Engagement at Jacob’S Pillow Is Supported, in Part, by a Leadership Contribution from Carole and Dan Burack

PILLOWNOTES JACOB’S PILLOW EXTENDS SPECIAL THANKS by Suzanne Carbonneau TO OUR VISIONARY LEADERS The PillowNotes comprises essays commissioned from our Scholars-in-Residence to provide audiences with a broader context for viewing dance. VISIONARY LEADERS form an important foundation of support and demonstrate their passion for and commitment to Jacob’s Pillow through It is said that the body doesn’t lie, but this is wishful thinking. All earthly creatures do it, only some more artfully than others. annual gifts of $10,000 and above. —Paul Taylor, Private Domain Their deep affiliation ensures the success and longevity of the It was Martha Graham, materfamilias of American modern dance, who coined that aphorism about the inevitability of truth Pillow’s annual offerings, including educational initiatives, free public emerging from movement. Considered oracular since its first utterance, over time the idea has only gained in currency as one of programs, The School, the Archives, and more. those things that must be accurate because it sounds so true. But in gently, decisively pronouncing Graham’s idea hokum, choreographer Paul Taylor drew on first-hand experience— $25,000+ observations about the world he had been making since early childhood. To wit: Everyone lies. And, characteristically, in his 1987 autobiography Private Domain, Taylor took delight in the whole business: “I eventually appreciated the artistry of a movement Carole* & Dan Burack Christopher Jones* & Deb McAlister PRESENTS lie,” he wrote, “the guilty tail wagging, the overly steady gaze, the phony humility of drooping shoulders and caved-in chest, the PAUL TAYLOR The Barrington Foundation Wendy McCain decorative-looking little shuffles of pretended pain, the heavy, monumental dances of mock happiness.” Frank & Monique Cordasco Fred Moses* DANCE COMPANY Hon. -

Curricula Guide Firstworks Arts Learning Presents Urban Bush

FirstWorks Arts Learning Presents Urban Bush Women Create Dance. Create Community For a special student performance/demonstration celebrating the history of UBW, movement for everyone & “Walking w/’Trane”. February 26, 2016 11:00 am @ The Vets 1 Avenue of the Arts Providence, RI 02903 Curricula Guide About FirstWorks Arts Learning FirstWorks has built deep, ongoing relationships with over 30 public and charter schools across Rhode Island to provide access to artists and help fill the gap left from severe public spending cuts. The program features workshops taught by leading artists who provide rich experiential learning in a classroom setting, allows students and their families to attend world-class performances, and provides professional development and lesson plans for teachers. “FirstWorks is clearly becoming a cultural beacon in its community and state. It’s very exciting to see how they’ve mobilized a community.” - National Endowment for the Arts Please visit us online at www.first-works.org for further information about Arts Learn- ing programming and season offerings. © FirstWorks 2016 WWW.FIRST-WORKS.ORG Table of Contents Theatre Etiquette. 1 Snapshot . .2 What is Modern Dance? . .5 African American Modern Dance . 7 Meet Jawole! . 8 Modern Dance Coloring Page! . 10 “Walking with ‘Trane” . 11 John Coltrane . 12 How People Feel About “A Love Supreme”. 14 Glossary. 16 K-4 Lesson: Jazz, Dance, & Poetry . 17 K-4 Lesson: Telling a Story Through Dance . 19 6-12 Lesson: Teaching Science Through Dance . 21 Additional Resources . 22 National Core Arts Standards . 23 Teacher Survey . 24 Student Survey . 25 WWW.FIRST-WORKS.ORG WWW.FIRST-WORKS.ORG | 1 1 Theatre Etiquette Be prepared and arrive early. -

Embodied History in Ralph Lemon's Come Home Charley Patton

“My Body as a Memory Map:” Embodied History in Ralph Lemon’s Come Home Charley Patton Doria E. Charlson I begin with the body, no way around it. The body as place, memory, culture, and as a vehicle for a cultural language. And so of course I’m in a current state of the wonderment of the politics of form. That I can feel both emotional outrageousness with my body as a memory map, an emotional geography of a particular American identity...1 Choreographer and visual artist Ralph Lemon’s interventions into the themes of race, art, identity, and history are a hallmark of his almost four-decade- long career as a performer and art-maker. Lemon, a native of Minnesota, was a student of dance and theater who began his career in New York, performing with multimedia artists such as Meredith Monk before starting his own company in 1985. Lemon’s artistic style is intermedial and draws on the visual, aural, musical, and physical to explore themes related to his personal history. Geography, Lemon’s trilogy of dance and intermedial artistic pieces, spans ten years of global, investigative creative processes aimed at unearthing the relationships among—and the possible representations of—race, art, identity, and history. Part one of the trilogy, also called Geography, premiered in 1997 as a dance piece and was inspired by Lemon’s journey to Africa, in particular to Côte d'Ivoire and Guinea, where Lemon sought to more deeply understand his identity as an African-American male artist. He subseQuently published a collection of writings, drawings, and notes which he had amassed during his research and travel in Africa under the title Geography: Art, Race, Exile. -

(The Efflorescence Of) Walter, an Exhibition by Ralph Lemon

Press Contact: Rachael Dorsey tel: 212 255-5793 ext. 14 fax: 212 645-4258 [email protected] For Immediate Release The Kitchen presents (The efflorescence of) Walter, an exhibition by Ralph Lemon New York, NY, April 17, 2007 – The Kitchen is pleased to present the first New York solo exhibition by choreographer, dancer, and visual artist Ralph Lemon. Titled (The efflorescence of) Walter, the show includes a body of work focused on the American South, featuring works-on-paper, a multiple-channel video installation, and other sculptural elements that explore history, memory, and memorialization. There will be an opening reception for the exhibition at The Kitchen (512 West 19th Street) on Friday, May 11 from 6- 8pm. Curated by Claire Tancons and Anthony Allen, the exhibition will be on view from May 11 – June 23, 2007. The Kitchen’s gallery hours are Tuesday-Friday, 12 to 6pm and Saturday, 11am to 6pm. Admission is Free. (The efflorescence of) Walter revolves around Lemon's collaborative relationship with Walter Carter, an African American man who has lived for almost a century in Yazoo City, Mississippi. Since 2002, Lemon and Carter have met twice a year and created a “collaborative meta-theater” in which actions scripted by Lemon are translated and transformed through Carter’s performance and improvisations. The exhibition weaves together videos of Walter’s actions with paintings, drawings and photographs by Lemon. Bringing together figures as varied as writer James Baldwin, artist Joseph Beuys, and Br’er Rabbit, a central character of African American folktales; as well as historical events from the Civil Rights era and cultural artifacts of the American South, this complex engagement with history, myth, and daily human existence explores how past, present, and future co-exist and at times collide. -

Harlem Intersection – Dancing Around the Double-Bind

HARLEM INTERSECTION – DANCING AROUND THE DOUBLE-BIND A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Judith A. Miller December, 2011 HARLEM INTERSECTION – DANCING AROUND THE DOUBLE-BIND Judith A. Miller Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________ _______________________________ Advisor School Director Robin Prichard Neil Sapienza _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the College Durand L. Pope Chand Midha, PhD _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School James Slowiak George R. Newkome, PhD _______________________________ Date ii TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………………………. 1 II. JOSEPHINE BAKER – C’EST LA VIE …………………..…….…………………..13 III. KATHERINE DUNHAM – CURATING CULTURE ON THE CONCERT STAGE …………………………………………………………..…………30 IV. PEARL PRIMUS – A PERSONAL CRUSADE …………………………...………53 V. CONCLUSION ……………………………………………………………...……….74 BIBLIOGRAPHY ……………………………………………………………………… 85 iii CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION “Black is Beautiful” became a popular slogan of the 1960s to represent rejection of white values of style and appearance. However, in the earlier decades of the twentieth century black women were daily deflecting slings and arrows thrown at them from all sides. Arising out of this milieu of adversity were Josephine Baker, Katherine Dunham, and Pearl Primus, performing artists whose success depended upon a willingness to innovate, to adapt to changing times, and to recognize and seize opportunities when and where they arose. Baker introduced her performing skills to New York audiences in the 1920s, followed by Dunham in the 1930s, and Primus in the 1940s. Although these decades resulted in an outpouring of cultural and artistic experimentation, for performing artists daring to cross traditional boundaries of gender and race, the obstacles were significant. -

Pentacle-40Th-Ann.-Gala-Program.Pdf

40 Table of Contents Welcome What is the landscape for emerging artists? Thoughts from the Founding Director Past & Current Pentacle Artists Tribute to Past Pentacle Staff Board of Directors- Celebration Committee- Staff Body Wisdom: Pentacle Celebrates Forty Years Tonight’s Program & Performers Event Sponsors & Donors Greetings Welcome Thank you for joining us tonight and celebrating this 40th Anniversary! In 1976 we opened our doors with a staff of four, providing what we called “cluster management” to four companies. Our mission was then and remains today to help artists do what they do best….create works of art. We have steadfastlyprovided day-to-day administration services as well as local and national innovative projects to individual artists, companies and the broader arts community. But we did not and could not do it alone. We have had the support of literally hundreds of arts administrators, presenters, publicists, funders, and individual supporters. So tonight is a celebration of Pentacle, yes, and also a celebration of our enormously eclectic community. We want to thank all of the artists who have donated their time and energies to present their work tonight, the Rubin Museum for providing such a beautiful space, and all of you for joining us and supporting Pentacle. Welcome and enjoy the festivities! Mara Greenberg Patty Bryan Director Board Chair Thoughts from the Founding Director What is the landscape for emerging dance artists? A question addressed forty years later. There are many kinds of dance companies—repertory troupes that celebrate the dances of a country or re- gion, exquisitely trained ensembles that spotlight a particular idiom or form—classical ballet or Flamenco or Bharatanatyam, among other classicisms, and avocational troupes of a hundred sorts that proudly share the dances, often traditional, of a hundred different cultures. -

Talking Black Dance: Inside Out

CONVERSATIONS ACROSS THE FIELD OF DANCE STUDIES Talking Black Dance: Inside Out OutsideSociety of Dance InHistory Scholars 2016 | Volume XXXVI Table of Contents A Word from the Guest Editors ................................................4 The Mis-Education of the Global Hip-Hop Community: Reflections of Two Dance Teachers: Teaching and In Conversation with Duane Lee Holland | Learning Baakasimba Dance- In and Out of Africa | Tanya Calamoneri.............................................................................42 Jill Pribyl & Ibanda Grace Flavia.......................................................86 TALKING BLACK DANCE: INSIDE OUT .................6 Mackenson Israel Blanchard on Hip-Hop Dance Choreographing the Individual: Andréya Ouamba’s Talking Black Dance | in Haiti | Mario LaMothe ...............................................................46 Contemporary (African) Dance Approach | Thomas F. DeFrantz & Takiyah Nur Amin ...........................................8 “Recipe for Elevation” | Dionne C. Griffiths ..............................52 Amy Swanson...................................................................................93 Legacy, Evolution and Transcendence When Dance Voices Protest | Dancing Dakar, 2011-2013 | Keith Hennessy ..........................98 In “The Magic of Katherine Dunham” | Gregory King and Ellen Chenoweth .................................................53 Whiteness Revisited: Reflections of a White Mother | Joshua Legg & April Berry ................................................................12 -

Dearest Home Kyle Abraham

KYLE ABRAHAM/ ABRAHAM.IN.MOTION DEAREST HOME TUE–SAT MAY 16–20, 2017 YBCA FORUM YBCA.ORG #KYLEABRAHAM A NOTE Our organization was founded in 1993 as a citizen institution that would be home KYLE ABRAHAM/ to the diverse local arts community while FROM THE serving to connect the Bay Area to the EXECUTIVE world. YBCA’s mission is to generate ABRAHAM.IN.MOTION culture that moves people. We believe DIRECTOR that culture—a collection of art, traditions, DEAREST HOME values, human experiences, and stories— is what enables us to act with imagination and creativity, to act socially, politically, CHOREOGRAPHY: KYLE ABRAHAM and with conviction. Culture instigates IN COLLABORATION WITH ABRAHAM.IN.MOTION change in the world. MUSIC COMPOSITION: JEROME BEGIN We believe that more and different kinds LIGHTING AND SET DESIGN: DAN SCULLY of people need to be defining culture today TEXT DESIGN: GLENN LIGON and that more people need to have access COSTUMES: KYLE ABRAHAM to cultural experiences that are relevant to their lives and their communities. We need PERFORMERS: MATTHEW BAKER, new definitions and new experiences that TAMISHA GUY, CATHERINE ELLIS KIRK, MARCELLA LEWIS, JEREMY “JAE” NEAL, CONNIE SHIAU bring people together regardless of their differences in order to make the inclusive and equitable culture we need today. We ABRAHAM.IN.MOTION believe that the arts should be on the The mission of Kyle Abraham/ For more information, to get involved, or front line of change and that cultural Abraham.In.Motion is to create an to purchase AIM merchandise, please visit institutions exist to spur and support big evocative, interdisciplinary body of work. -

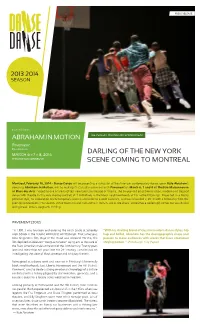

Darling of the New York Scene Coming to Montreal

Press RELEASE » United-States ABRAHAM.IN.MOTION THE PERFECT OUTING FOR SPRING BREAK Pavement Kyle Abraham MARCH 6 » 7 » 8, 2014 DARLING OF THE NEW YORK THÉÂTRE MAISONNEUVE SCENE COMING TO MONTREAL Montreal, February 10, 2014 – Danse Danse will be presenting a rising star of the American contemporary dance scene. Kyle Abraham’s company Abraham.In.Motion, will be making its Canadian première with Pavement on March 6, 7 and 8 at Théâtre Maisonneuve at Place des Arts. Praised as one of the brightest new talents in the age of Obama, the 36-year-old artist blends urban, modern and classical dance with theatre in this very moving portrait of 7 individuals in the black neighbourhoods of his native Pittsburgh. Presented in a highly personal style, his exploration of contemporary issues is accessible to a wide audience, and was rewarded in 2013 with a fellowship from the prestigious MacArthur Foundation. While major cultural institutions in the U.S. are in dire straits, sometimes a perfect gift comes our way during spring break. Urban, poignant, thrilling. PAVEMENT (2012) “In 1991, I was fourteen and entering the ninth grade at Schenley ”With his riveting blend of classical modern-dance styles, hip High School in the historic Hill District of Pittsburgh. That same year, hop and ballet, Abraham has the choregographic chops and John Singleton’s film, Boyz N The Hood was released. For me, the passion to move audiences with works that have emotional film depicted an idealized “Gangsta Boheme” laying aim to the state of staying power. “ (Pittsburgh City Paper) the Black American male at the end of the 20th century. -

Art Works Grants

National Endowment for the Arts — December 2014 Grant Announcement Art Works grants Discipline/Field Listings Project details are as of November 24, 2014. For the most up to date project information, please use the NEA's online grant search system. Art Works grants supports the creation of art that meets the highest standards of excellence, public engagement with diverse and excellent art, lifelong learning in the arts, and the strengthening of communities through the arts. Click the discipline/field below to jump to that area of the document. Artist Communities Arts Education Dance Folk & Traditional Arts Literature Local Arts Agencies Media Arts Museums Music Opera Presenting & Multidisciplinary Works Theater & Musical Theater Visual Arts Some details of the projects listed are subject to change, contingent upon prior Arts Endowment approval. Page 1 of 168 Artist Communities Number of Grants: 35 Total Dollar Amount: $645,000 18th Street Arts Complex (aka 18th Street Arts Center) $10,000 Santa Monica, CA To support artist residencies and related activities. Artists residing at the main gallery will be given 24-hour access to the space and a stipend. Structured as both a residency and an exhibition, the works created will be on view to the public alongside narratives about the artists' creative process. Alliance of Artists Communities $40,000 Providence, RI To support research, convenings, and trainings about the field of artist communities. Priority research areas will include social change residencies, international exchanges, and the intersections of art and science. Cohort groups (teams addressing similar concerns co-chaired by at least two residency directors) will focus on best practices and develop content for trainings and workshops. -

Tools of Engagement in Urban Bush Women's Hairstories Rachel Howell

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 Tools of Engagement in Urban Bush Women's Hairstories Rachel Howell Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF VISUAL ARTS, THEATER & DANCE TOOLS OF ENGAGEMENT IN URBAN BUSH WOMEN’S HAIRSTORIES By RACHEL HOWELL A thesis submitted to the School of Dance in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2011 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Rachel Howell defended on March 30, 2011. _______________________________________ Tricia Young Professor Directing Thesis _______________________________________ Sally Sommer University Representative _______________________________________ Jennifer Atkins Committee Member _______________________________________ Lynda Davis Committee Member Approved: _____________________________________ Patty Phillips, Chair, School of Dance _____________________________________ Sally McRorie , Dean, College of Visual Arts, Theatre & Dance The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii For Lance iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the perspective and humor of my brother Rick, the love and support of my sister-in-law Kelly, and the inspiration of my nieces, Jacqueline, Jourdan, and Jazmyn. Additionally, Amy Cassello, my boss at Urban Bush Women, gave me full access