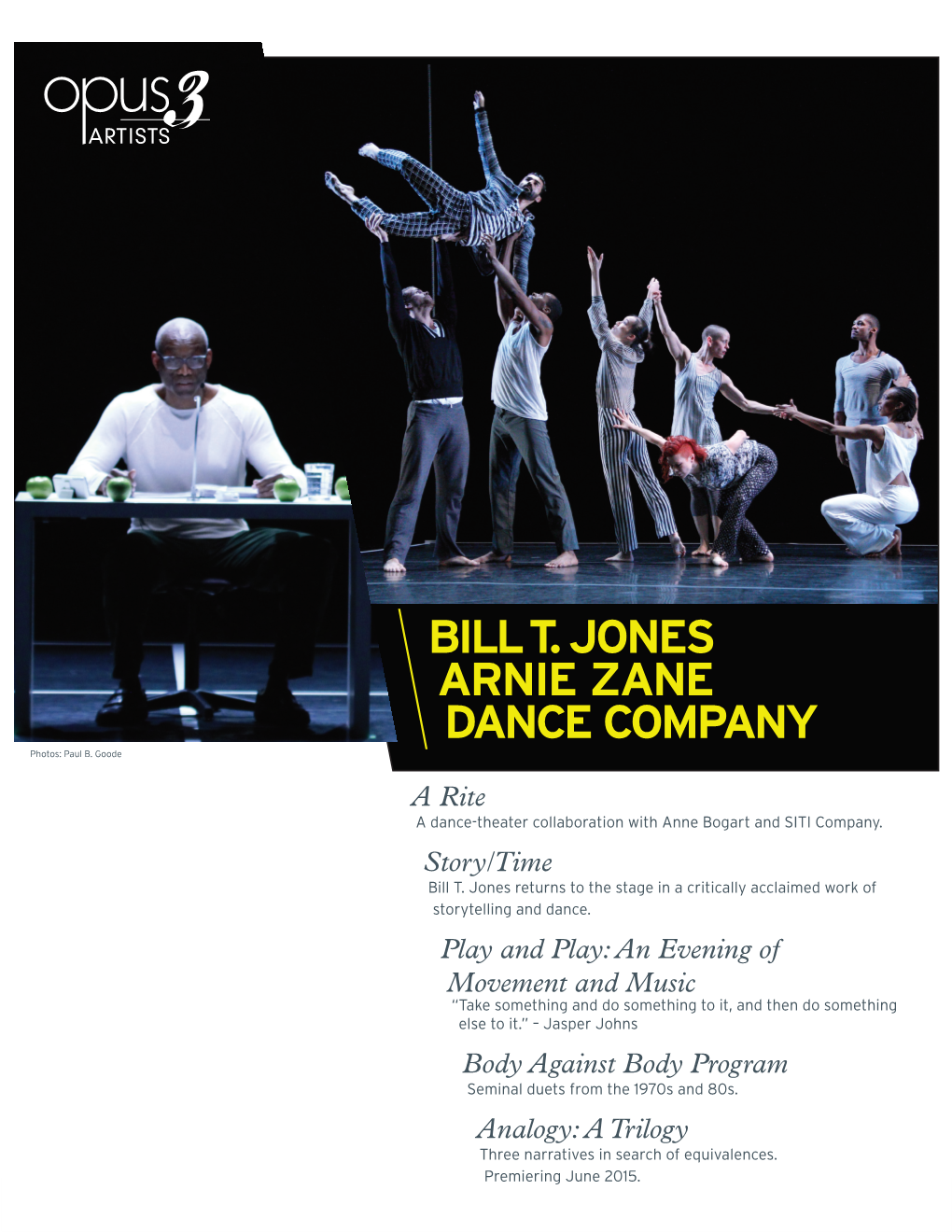

A Rite Story/Time Play and Play: an Evening of Movement and Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“White Christmas”—Bing Crosby (1942) Added to the National Registry: 2002 Essay by Cary O’Dell

“White Christmas”—Bing Crosby (1942) Added to the National Registry: 2002 Essay by Cary O’Dell Crosby’s 1945 holiday album Original release label “Holiday Inn” movie poster With the possible exception of “Silent Night,” no other song is more identified with the holiday season than “White Christmas.” And no singer is more identified with it than its originator, Bing Crosby. And, perhaps, rightfully so. Surely no other Christmas tune has ever had the commercial or cultural impact as this song or sold as many copies--50 million by most estimates, making it the best-selling record in history. Irving Berlin wrote “White Christmas” in 1940. Legends differ as to where and how though. Some say he wrote it poolside at the Biltmore Hotel in Phoenix, Arizona, a reasonable theory considering the song’s wishing for wintery weather. Some though say that’s just a good story. Furthermore, some histories say Berlin knew from the beginning that the song was going to be a massive hit but another account says when he brought it to producer-director Mark Sandrich, Berlin unassumingly described it as only “an amusing little number.” Likewise, Bing Crosby himself is said to have found the song only merely adequate at first. Regardless, everyone agrees that it was in 1942, when Sandrich was readying a Christmas- themed motion picture “Holiday Inn,” that the song made its debut. The film starred Fred Astaire and Bing Crosby and it needed a holiday song to be sung by Crosby and his leading lady, Marjorie Reynolds (whose vocals were dubbed). Enter “White Christmas.” Though the film would not be seen for many months, millions of Americans got to hear it on Christmas night, 1941, when Crosby sang it alone on his top-rated radio show “The Kraft Music Hall.” On May 29, 1942, he recorded it during the sessions for the “Holiday Inn” album issued that year. -

The Twenty Greatest Music Concerts I've Ever Seen

THE TWENTY GREATEST MUSIC CONCERTS I'VE EVER SEEN Whew, I'm done. Let me remind everyone how this worked. I would go through my Ipod in that weird Ipod alphabetical order and when I would come upon an artist that I have seen live, I would replay that concert in my head. (BTW, since this segment started I no longer even have an ipod. All my music is on my laptop and phone now.) The number you see at the end of the concert description is the number of times I have seen that artist live. If it was multiple times, I would do my best to describe the one concert that I considered to be their best. If no number appears, it means I only saw that artist once. Mind you, I have seen many artists live that I do not have a song by on my Ipod. That artist is not represented here. So although the final number of concerts I have seen came to 828 concerts (wow, 828!), the number is actually higher. And there are "bar" bands and artists (like LeCompt and Sam Butera, for example) where I have seen them perform hundreds of sets, but I counted those as "one," although I have seen Lecompt in "concert" also. Any show you see with the four stars (****) means they came damn close to being one of the Top Twenty, but they fell just short. So here's the Twenty. Enjoy and thanks so much for all of your input. And don't sue me if I have a date wrong here and there. -

Paul Taylor Dance Company’S Engagement at Jacob’S Pillow Is Supported, in Part, by a Leadership Contribution from Carole and Dan Burack

PILLOWNOTES JACOB’S PILLOW EXTENDS SPECIAL THANKS by Suzanne Carbonneau TO OUR VISIONARY LEADERS The PillowNotes comprises essays commissioned from our Scholars-in-Residence to provide audiences with a broader context for viewing dance. VISIONARY LEADERS form an important foundation of support and demonstrate their passion for and commitment to Jacob’s Pillow through It is said that the body doesn’t lie, but this is wishful thinking. All earthly creatures do it, only some more artfully than others. annual gifts of $10,000 and above. —Paul Taylor, Private Domain Their deep affiliation ensures the success and longevity of the It was Martha Graham, materfamilias of American modern dance, who coined that aphorism about the inevitability of truth Pillow’s annual offerings, including educational initiatives, free public emerging from movement. Considered oracular since its first utterance, over time the idea has only gained in currency as one of programs, The School, the Archives, and more. those things that must be accurate because it sounds so true. But in gently, decisively pronouncing Graham’s idea hokum, choreographer Paul Taylor drew on first-hand experience— $25,000+ observations about the world he had been making since early childhood. To wit: Everyone lies. And, characteristically, in his 1987 autobiography Private Domain, Taylor took delight in the whole business: “I eventually appreciated the artistry of a movement Carole* & Dan Burack Christopher Jones* & Deb McAlister PRESENTS lie,” he wrote, “the guilty tail wagging, the overly steady gaze, the phony humility of drooping shoulders and caved-in chest, the PAUL TAYLOR The Barrington Foundation Wendy McCain decorative-looking little shuffles of pretended pain, the heavy, monumental dances of mock happiness.” Frank & Monique Cordasco Fred Moses* DANCE COMPANY Hon. -

Phased Reopening of Montana's Economy TWIN

Accuracy is essential. Reliable local news has never been more important. A special thank you to all of our loyal advertisers and readers who support local journalism each week. We're grateful! THE LOCAL NEWS OF THE MADISON VALLEY,Buy RUBYOne GetVALLEY One! AND SURROUNDING AREAS Buy a 1-year subscription, get another one free to give a friend. MONTANA’S OLDEST PUBLISHING WEEKLYTo get set up, NEWSPAPER. contact [email protected] ESTABLISHED or 406-596-0661 1873 75¢ | Volume 148, Issue 20 Thursday, April 23, 2020 Need Help? The Montana Heritage Commission is helping those at risk individuals in Virginia City who need assistance getting medical prescriptions and Emergency Essentials. Please call 406-369-8147 to let us help. [email protected] | 406-843-5247 MONTANA COVID-19 UPDATE EVERYONE’S GOT A MASK! Phased reopening of Montana’s economy By HANNAH KEARSE and abiding to social distanc- gradually reopen Montana’s [email protected] ing recommendations. economy. The directives that are “I’m a little sensitive be- ov. Bullock an- lifted or reduced will allow cause we just had Easter a few nounced a phased local governments to decide days ago,” Madison County reopening of what is best for its unique Public Health Nurse Melissa Montana'sG economy, which community. The phases of Brummel said. will begin when all directives reopening the state’s economy The holiday brought some expire April 24. More details will be in accordance with people together spite social of the gradual process will be the Montana Public Health distancing recommendations, announced later in the week. -

MARTIN PAKLEDINAZ, Costume Designer

THE ELIXIR OF LOVE FOR FAMILIES PRODUCTION TEAM BIOGRAPHY MARTIN PAKLEDINAZ, Costume Designer Martin Pakledinaz is an American Tony Award-winning costume designer for stage and film. His work on Broadway includes The Pajama Game, The Trip to Bountiful, Wonderful Town, Thoroughly Modern Millie, Kiss Me, Kate, The Boys From Syracuse, The Diary Of Anne Frank, A Year With Frog And Toad, The Life, Anna Christie, The Father, and Golden Child. Off-Broadway work includes Two Gentlemen of Verona, Andrew Lippa's The Wild Party, Kimberly Akimbo, Give Me Your Answer, Do, Juvenalia, The Misanthrope, Kevin Kline's Hamlet, Twelve Dreams, Waste, and Troilus and Cressida. He won two Tony Awards for designing the costumes of Thoroughly Modern Millie and the 2000 revival of Kiss Me Kate, which also earned him the Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Costume Design. He has designed plays for the leading regional theatres of the United States, and the Royal Dramatic Theatre of Sweden. Opera credits include works at the New York Metropolitan Opera and the New York City Opera, as well as opera houses in Seattle, Los Angeles, St. Louis, Sante Fe, Houston, and Toronto. European houses include Salzburg, Paris, Amsterdam, Brussels, Helsinki, Gothenburg, and others. His dance credits include a long collaboration with Mark Morris, and dances for such diverse choreographers as George Balanchine, Eliot Feld, Deborah Hay, Daniel Pelzig, Kent Stowell, Helgi Tomasson, and Lila York. His collaborators in theatre include Rob Ashford, Gabriel Barre, Michael Blakemore, Scott Ellis, Colin Graham, Sir Peter Hall, Michael Kahn, James Lapine, Stephen Lawless, Kathleen Marshall, Charles Newell, David Petrarca, Peter Sellars, Bartlett Sher, Stephen Wadsworth, Garland Wright, and Francesca Zambello. -

Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still Calling Her Q!

1 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In InfiniteBody art and creative consciousness by Eva Yaa Asantewaa Tuesday, May 6, 2014 Your Host Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still calling her Q! Eva Yaa Asantewaa Follow View my complete profile My Pages Home About Eva Yaa Asantewaa Getting to know Eva (interview) Qurrat Ann Kadwani Eva's Tarot site (photo Bolti Studios) Interview on Tarot Talk Contact Eva Name Email * Message * Send Contribute to InfiniteBody Subscribe to IB's feed Click to subscribe to InfiniteBody RSS Get InfiniteBody by Email Talented and personable Qurrat Ann Kadwani (whose solo show, They Call Me Q!, I wrote about Email address... Submit here) is back and, I hope, every bit as "wicked smart and genuinely funny" as I observed back in September. Now she's bringing the show to the Off Broadway St. Luke's Theatre , May 19-June 4, Mondays at 7pm and Wednesdays at 8pm. THEY CALL ME Q is the story of an Indian girl growing up in the Boogie Down Bronx who gracefully seeks balance between the cultural pressures brought forth by her traditional InfiniteBody Archive parents and wanting acceptance into her new culture. Along the journey, Qurrat Ann Kadwani transforms into 13 characters that have shaped her life including her parents, ► 2015 (222) Caucasian teachers, Puerto Rican classmates, and African-American friends. Laden with ▼ 2014 (648) heart and abundant humor, THEY CALL ME Q speaks to the universal search for identity ► December (55) experienced by immigrants of all nationalities. ► November (55) Program, schedule and ticket information ► October (56) ► September (42) St. -

Resume 2017.Pgs

JANE LABANZ www.janelabanz.com Height: 5’5” / Weight: 120 212 300 5653 Soprano/Mix/Light Belt AEA SAG/AFTRA Strong High Notes 330 West 42nd Street, 18th Floor New York, NY 10036 212-629-9112 [email protected] BROADWAY/NATIONAL TOURS Director Anything Goes Hope u/s (Broadway and National Tour) Jerry Zaks The King and I Anna (Sandy Duncan / Stefanie Powers standby) Baayork Lee The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas Ginger (Doatsey Mae u/s) Thommie Walsh (Cast album, w/ Ann-Margret) Eric Schaeffer Annie Grace Farrell Bob Fitch 42nd Street Phyllis Dale (Peggy u/s) Mark Bramble The Sound of Music (w/ Marie Osmond) Swing/Dance Captain Jamie Hammerstein Bye Bye Birdie (w/ Tommy Tune/Anne Reinking) Kim u/s (to Susan Egan) Gene Saks Dr. Dolittle (w/ Tommy Tune) Puddleby Tommy Tune Cats Jelly/Jenny/Swing David Taylor REGIONAL THEATRE Tuck Everlasting (World Premiere /Alliance Theatre) Older Winnie (Nanna u/s) Casey Nicholaw (Dir.) Love Story (American Premiere) Alison Barrett Walnut Street Theatre A Little Night Music Mrs. Nordstrom / Dance Captain Cincinnati Playhouse 9 to 5 Violet Newstead Tent Theatre I Love a Piano Eileen Milwaukee Repertory Always…Patsy Cline Louise Seger New Harmony Theatre The Cocoanuts (Helen Hayes Award, Best Musical) Polly Potter Arena Stage Noises Off Brooke Ashton Totem Pole Playhouse Cinderella Fairy Godmother / Queen u/s North Shore Music Theatre The Nerd Clelia Waldgrave Totem Pole Playhouse The Music Man Marian Paroo Pittsburgh Playhouse George M! Nellie Cohan Theatre by the Sea George M! Agnes Nolan (plus 9 other -

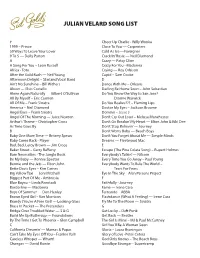

Julian Velard Song List

JULIAN VELARD SONG LIST # Cheer Up Charlie - Willy Wonka 1999 – Prince Close To You — Carpenters 50 Ways To Leave Your Lover Cold As Ice —Foreigner 9 To 5 — Dolly Parton Cracklin’ Rosie — Neil Diamond A Crazy — Patsy Cline A Song For You – Leon Russell Crazy For You - Madonna Africa - Toto Crying — Roy Orbison After the Gold Rush — Neil Young Cupid – Sam Cooke Afternoon Delight – Starland Vocal Band D Ain’t No Sunshine – Bill Withers Dance With Me – Orleans Alison — Elvis Costello Darling Be Home Soon – John Sebastian Alone Again Naturally — Gilbert O’Sullivan Do You Know the Way to San Jose? — All By Myself – Eric Carmen Dionne Warwick All Of Me – Frank Sinatra Do You Realize??? – Flaming Lips America – Neil Diamond Doctor My Eyes – Jackson Browne Angel Eyes – Frank Sinatra Domino – Jesse J Angel Of The Morning — Juice Newton Don’t Cry Out Loud – Melissa Manchester Arthur’s Theme – Christopher Cross Don’t Go Breakin’ My Heart — Elton John & Kiki Dee As Time Goes By Don’t Stop Believin’ — Journey B Don’t Worry Baby — Beach Boys Baby One More Time — Britney Spears Don’t You Forget About Me — Simple Minds Baby Come Back - Player Dreams — Fleetwood Mac Bad, Bad, Leroy Brown — Jim Croce E Baker Street – Gerry Raerty Escape (The Pina Colata Song) – Rupert Holmes Bare Necessities - The Jungle Book Everybody’s Talkin’ — Nilsson Be My Baby — Ronnie Spector Every Time You Go Away – Paul Young Bennie and the Jets — Elton John Everybody Wants To Rule The World – Bette Davis Eyes – Kim Carnes Tears For Fears Big Yellow Taxi — Joni Mitchell Eye In -

Press Release: for Immediate Release

PRESS RELEASE: FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Mike Michelon, Executive Director 734-994-5899, [email protected] #### Ann Arbor Summer Festival Announces First Shows of the Season ANN ARBOR MI (February 12, 2020) – The Ann Arbor Summer Festival is pleased to announce three headlining ticketed performances for the festival’s 2020 season. Festival Executive Director Mike Michelon shares, “We are thrilled to announce three of our ticketed shows early this season. Our 37th season will feature an eclectic mix of a Broadway icon, a world class illusionist, and an infamous comedy troupe returning for their 21st season.” The remaining ticketed performances will be announced in March. The full Top of the Park season will be announced on May 1. Festival Ticket Information Tickets On Sale: Thursday, February 13 at 9 am (General Public) Online: tickets.a2sf.org By Phone: (734) 764-2538 or toll-free in Michigan at (800) 221-1229 In Person: Michigan League Ticket Office, 911 N. University Ave, Ann Arbor MI 48109 Festival Venue Information Power Center for the Performing Arts: 121 Fletcher Street, Ann Arbor, MI Hill Auditorium: 825 N University Ave, Ann Arbor, MI Zingerman’s Greyline: 100 N Ashley St, Ann Arbor, MI Top of the Park: 915 E Washington St, Ann Arbor, MI Ann Arbor Summer Festival 2020 Ticketed Performances Scott Silven: Wonders at Dusk Wednesday-Friday, June 24-26 at 6:30/7pm Zingerman’s Greyline $55 (plus fees), $35 (plus fees), ages 12-18 Scott Silven is an incomparable modern marvel, and he returns to A2SF after a sold-out run in 2018. -

The New Yorker-20180326.Pdf

PRICE $8.99 MAR. 26, 2018 MARCH 26, 2018 6 GOINGS ON ABOUT TOWN 17 THE TALK OF THE TOWN Amy Davidson Sorkin on White House mayhem; Allbirds’ moral fibres; Trump’s Twitter blockees; Sheila Hicks looms large; #MeToo and men. ANNALS OF THEATRE Michael Schulman 22 The Ascension Marianne Elliott and “Angels in America.” SHOUTS & MURMURS Ian Frazier 27 The British Museum of Your Stuff ONWARD AND UPWARD WITH THE ARTS Hua Hsu 28 Hip-Hop’s New Frontier 88rising’s Asian imports. PROFILES Connie Bruck 36 California v. Trump Jerry Brown’s last term as governor. PORTFOLIO Sharif Hamza 48 Gun Country with Dana Goodyear Firearms enthusiasts of the Parkland generation. FICTION Tommy Orange 58 “The State” THE CRITICS A CRITIC AT LARGE Jill Lepore 64 Rachel Carson’s writings on the sea. BOOKS Adam Kirsch 73 Two new histories of the Jews. 77 Briefly Noted THE CURRENT CINEMA Anthony Lane 78 “Tomb Raider,” “Isle of Dogs.” POEMS J. Estanislao Lopez 32 “Meditation on Beauty” Lucie Brock-Broido 44 “Giraffe” COVER Barry Blitt “Exposed” DRAWINGS Roz Chast, Zachary Kanin, Seth Fleishman, William Haefeli, Charlie Hankin, P. C. Vey, Bishakh Som, Peter Kuper, Carolita Johnson, Tom Cheney, Emily Flake, Edward Koren SPOTS Miguel Porlan CONTRIBUTORS The real story, in real time. Connie Bruck (“California v. Trump,” Hua Hsu (“Hip-Hop’s New Frontier,” p. 36) has been a staff writer since 1989. p. 28), a staff writer, is the author of “A She has published three books, among Floating Chinaman.” them “The Predators’ Ball.” Jill Lepore (A Critic at Large, p. -

The Gilder Lehrman Collection

the Gilder Lehrman institute of american history the Gilder Lehrman institute of american history 19 west 44th street, suite 500 new york, ny 10036 646-366-9666 www.gilderlehrman.org Annual Report 2001 Board of Advisors Co-Chairmen Richard Gilder Lewis E. Lehrman President James G. Basker Executive Director Lesley S. Herrmann Advisory Board Dear Board Members and Friends, Joyce O. Appleby, Professor of History Emerita, James O. Horton, Benjamin Banneker Professor University of California Los Angeles of American Studies and History, George We present the Institute’s annual report for 2001, a year in which William F. Baker, President, Channel Thirteen/WNET Washington University Thomas H. Bender, University Professor of the Kenneth T. Jackson, Jacques Barzun Professor the study of American history took on a new importance. Our Humanities, New York University of History, Columbia University and President, activities continue to expand, and we look forward to significant Lewis W. Bernard, Chairman, Classroom Inc. New-York Historical Society David W. Blight, Class of 1959 Professor of History Daniel P. Jordan, President, Thomas Jefferson growth in 2002. and Black Studies, Amherst College Memorial Foundation Gabor S. Boritt, Robert C. Fluhrer Professor of David M. Kennedy, Donald J. McLachlan Professor Civil War Studies, Gettysburg College of History, Stanford University (co-chair, Advisory Board) Roger G. Kennedy, Director Emeritus, Richard Brookhiser, Senior Editor, National Review National Park Service James G. Basker Lesley S. Herrmann Kenneth L. Burns, Filmmaker Roger Kimball, Managing Editor, The New Criterion President Executive Director David B. Davis, Sterling Professor of History Emeritus, Richard C. Levin, President, Yale University Yale University (co-chair, Advisory Board) James M. -

To Get a Job in a Broadway Chorus, Go Into Your Dance:" Education for Careers in Musical Theatre Dance

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Master's Theses Student Research 9-30-2019 "To Get a Job in a Broadway Chorus, Go into Your Dance:" Education for Careers in Musical Theatre Dance Lauran Stanis [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digscholarship.unco.edu/theses Recommended Citation Stanis, Lauran, ""To Get a Job in a Broadway Chorus, Go into Your Dance:" Education for Careers in Musical Theatre Dance" (2019). Master's Theses. 108. https://digscholarship.unco.edu/theses/108 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © 2019 LAURAN STANIS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School “TO GET A JOB IN A BROADWAY CHORUS, GO INTO YOUR DANCE:” EDUCATION FOR CAREERS IN MUSICAL THEATRE DANCE A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Lauran Stanis College of Performing and Visual Arts School of Theatre Arts and Dance Dance Education December 2019 This Thesis by: Lauran Stanis Entitled: “To Get a Job in a Broadway Chorus, Go into Your Dance:” Education for Careers in Musical Theatre Dance has been approved as meeting the requirement for the Degree of Masters in Arts in the College of Performing and Visual Arts in the School of Theatre and Dance, Program of Dance Education Accepted by the Thesis Committee: _________________________________________________ Sandra L.