A Revision of Phyllanthus (Euphorbiaceae) in the Continental United States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pharmacophore PHYLLANTHUS PLANTS in PHOTOPROTECTION

Pharmacophore, 8(3) 2017, Pages: 1-10 Pharmacophore ISSN-2229-5402 Journal home page: http://www.pharmacophorejournal.com PHYLLANTHUS PLANTS IN PHOTOPROTECTION: A BROAD SPECTRUM OF MOLECULAR MECHANISMS Ivette María Menéndez-Perdomo1,2, Ángel Sánchez-Lamar1* 1. Department of Plant Biology, Faculty of Biology, University of Havana, 25St, 455 between I and J, CP 10400, Havana, Cuba 2. Current address: Department of Biological Sciences, University of Calgary, 2500 University Drive NW, Calgary, AB T2N 1N4, Canada. ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Received: 05th Mar 2017 During the past few decades, there has been an increased scientific interest to prevent or amend the Received in revised form: consequences of human exposure to the detrimental effects of sunlight ultraviolet (UV) radiation. 07th Apr 2017 Environmental UV radiation cause direct and indirect DNA damage, inducing mutations, and Accepted: triggering associated diseases, such as skin cancer. Many photoprotection strategies are currently 28th Apr 2017 available, as this has become a core issue on public healthcare. In this context, many Available online: phytocomponents had shown photoprotective properties in different experimental models. Plants 29th May 2017 in the genus Phyllanthus (Phyllanthaceae) are widely used in traditional medicine by ethnics from all over the world, and recent investigations support their genoprotective activity against UV radiation. In the present review, we summarize UV-related DNA photodamages and several Keywords: Phyllanthus, photoprotection, strategies for its prevention such as the use of phytocomponents. We update the current knowledge UV, antioxidant, DNA repair concerning the photoprotective properties of several Phyllanthus species, putting emphasis on studies carried out in the last decade. We examine different molecular mechanisms described to . -

Flora of Oakmont Park, City of Fort Worth Tarrant Co

Flora of Oakmont Park, City of Fort Worth Tarrant Co. Updated 09 April 2015 150 species Oakmont Park FLOWER STATE/FED FAMILY OLD FAMILY LATIN NAME COMMON NAME BLOOM PERIOD Expr1006 COLOR RANK Amaryllidaceae Alliaceae=Liliaceae Allium drummondii Drummond's Onion ++345++++++++++ White/Pink Amaryllidaceae Alliaceae=Liliaceae Nothoscordum bivalve Crow-Poison +F345+++910++++ White Apiaceae Chaerophyllum tainturieri var. Smooth Chervil ++34+++++++++++ White tainturieri Apiaceae Cymopterus macrohizus Bigroot Cymopterus JF34+++++++++++ White/Pink Apiaceae Eryngium leavenworthii Leavenworth Eryngo ++++++789++++++ Purple Apiaceae Polytaenia nuttallii=texana Prairie Parsley +++45++++++++++ Yellow Apiaceae Sanicula canadensis Canada Sanicle +++456+++++++++ White Apiaceae Torilis arvensis Hedge Parsley +++456+++++++++ White Apiaceae Torilis nodosa Knotted Hedge-Parsley +++456+++++++++ White Apocynaceae Asclepidaceae Asclepias asperula ssp. capricornu Antelope Horns +++45678910++++ White Aquifoliaceae Ilex decidua Possum Haw ++345++++++++++ White Asparagaceae Agavaceae Yucca arkansana Arkansas Yucca +++45++++++++++ White Asparagaceae Agavaceae Yucca necopina Glen Rose Yucca ++++5++++++++++ White S1S2 S1S2 Asparagaceae Agavaceae Yucca pallida Pale Leaf Yucca ++++5++++++++++ White S3 S3 Asteraceae Ambrosia psilostachya Western Ragweed +++++++891011++ Inconspicuous Asteraceae Amphiachyris Common Broomweed ++++++7891011++ Yellow dracunculoides=Gutierrezia Asteraceae Artemisia ludoviciana ssp. mexicana Mexican Sagebrush +++++++++1011++ Yellowish White Asteraceae -

The Relation Between Road Crack Vegetation and Plant Biodiversity in Urban Landscape

Int. J. of GEOMATE, June, 2014, Vol. 6, No. 2 (Sl. No. 12), pp. 885-891 Geotech., Const. Mat. & Env., ISSN:2186-2982(P), 2186-2990(O), Japan THE RELATION BETWEEN ROAD CRACK VEGETATION AND PLANT BIODIVERSITY IN URBAN LANDSCAPE Taizo Uchida1, JunHuan Xue1,2, Daisuke Hayasaka3, Teruo Arase4, William T. Haller5 and Lyn A. Gettys5 1Faculty of Engineering, Kyushu Sangyo University, Japan; 2Suzhou Polytechnic Institute of Agriculture, China; 3Faculty of Agriculture, Kinki University, Japan; 4Faculty of Agriculture, Shinshu University, Japan; 5Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants, University of Florida, USA ABSTRACT: The objective of this study is to collect basic information on vegetation in road crack, especially in curbside crack of road, for evaluating plant biodiversity in urban landscape. A curbside crack in this study was defined as a linear space (under 20 mm in width) between the asphalt pavement and curbstone. The species composition of plants invading curbside cracks was surveyed in 38 plots along the serial National Route, over a total length of 36.5 km, in Fukuoka City in southern Japan. In total, 113 species including native plants (83 species, 73.5%), perennial herbs (57 species, 50.4%) and woody plants (13 species, 11.5%) were recorded in curbside cracks. Buried seeds were also obtained from soil in curbside cracks, which means the cracks would possess a potential as seed bank. Incidentally, no significant differences were found in the vegetation characteristics of curbside cracks among land-use types (Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test, P > 0.05). From these results, curbside cracks would be likely to play an important role in offering habitat for plants in urban area. -

Euphorbia Telephioides (Euphorbiaceae)

Genetic diversity within a threatened, endemic North American species, Euphorbia telephioides (Euphorbiaceae) Dorset W. Trapnell, J. L. Hamrick & Vivian Negrón-Ortiz Conservation Genetics ISSN 1566-0621 Conserv Genet DOI 10.1007/s10592-012-0323-4 1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by Springer Science+Business Media B.V.. This e-offprint is for personal use only and shall not be self- archived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your work, please use the accepted author’s version for posting to your own website or your institution’s repository. You may further deposit the accepted author’s version on a funder’s repository at a funder’s request, provided it is not made publicly available until 12 months after publication. 1 23 Author's personal copy Conserv Genet DOI 10.1007/s10592-012-0323-4 RESEARCH ARTICLE Genetic diversity within a threatened, endemic North American species, Euphorbia telephioides (Euphorbiaceae) Dorset W. Trapnell • J. L. Hamrick • Vivian Negro´n-Ortiz Received: 23 September 2011 / Accepted: 20 January 2012 Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2012 Abstract The southeastern United States and Florida which it occurs, Gulf (0.084), Franklin (0.059) and Bay support an unusually large number of endemic plant spe- Counties (0.033), were also quite low. Peripheral popula- cies, many of which are threatened by anthropogenic tions did not generally have reduced genetic variation habitat disturbance. As conservation measures are under- although there was significant isolation by distance. Rare- taken and recovery plans designed, a factor that must be faction analysis showed a non-significant relationship taken into consideration is the genetic composition of the between allelic richness and actual population sizes. -

Gender Variation in CROTON CALIFORNICUS (EUPHORBIACEAE)

Loma Linda University TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects 9-1999 Gender Variation in CROTON CALIFORNICUS (EUPHORBIACEAE) James Lynwood Smith II Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/etd Part of the Biology Commons, and the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Smith, James Lynwood II, "Gender Variation in CROTON CALIFORNICUS (EUPHORBIACEAE)" (1999). Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects. 946. https://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/etd/946 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects by an authorized administrator of TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LOMA LINDA UNIVERSITY Graduate School GENDER VARIATION IN CROTON CALIFORNICUS (EUPHORBIACEAE) by James Lynwood Smith II A Dissertation in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Biology September 1999 Each person whose signature appears below certifies that this dissertation in their opinion is adequate, in scope and quality, as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. , Co-Chairperson , Co-Chairperson Gary L. Bradley, Professor at La Sierra University ii Acknowledgments I wish to thank Ron Carter and Brad Martin for their guidance, assistance, and comments. I am grateful to the other members of my guidance committee, Gary Bradley, Bob Cushman, and Bill Hayes, for their advice and comments. I am also grateful to Aida Smith for assisting with data collection, data entry, and providing comments. -

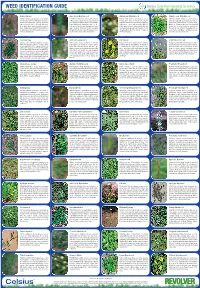

Weed Identification Guide

WEED IDENTIFICATION GUIDE Carpetgrass American Burnweed Common Chickweed Mouse-ear Chickweed Axonopus affi nis (Carpetgrass) is a mat-forming Erechtites hieracifolia (American Burnweed Stellaria media (Common Chickweed) is a mat- Cerastium vulgatum (Mouse-ear Chickweed) is a perennial that can be identifi ed by its smooth leaf or Fireweed) is a robust summer annual identifi ed forming winter annual or short-lived perennial in winter perennial with alternating leaves that are blades with rounded tips. Typically, a few long by its spiraling, alternating elliptic to lance-shaped temperate regions and is identifi ed by alternating, oblong and covered with hair. Prostrate overall, hairs are present on the leaf sheath at the base leaves with narrow, sharp-pointed bases on the shiny leaves - egg or oval, to broadly elliptic, in Mouse-ear Chickweed will have several upright of the blade. Often found coexisting in centipede lower part of the stem and clasping based on the shape. Upper leaves are without petiole, while the stems. The weed can further be identifi ed by lawns. Carpetgrass is found in the Coastal Plain of upper. American Burnweed fl owers late-spring lower leaves have sparsely, hairy long petiole. Found the white fl owers containing fi ve pedals that are the Gulf states, north to North Carolina and west to through fall and can be found throughout most of throughout North America, with the exception of notched at the ends. Mouse-ear Chickweed can be Arkansas and Oklahoma. Eastern, Central and Southern United States. the Rocky Mountains. found throughout the United States. Clumpy Rye Annual Lespedeza Dandelion Plantain, Bracted Lolium perenne (Perennial ryegrass) or Lolium Kummerowia striata (Common or Annual Taraxacum officinale (Dandelion) is a stemless Plantago aristata (Bracted Plantain) is a winter multifl orum (Annual ryegrass) is a winter annual Lespedeza) is a freely-branched summer annual perennial. -

State of New York City's Plants 2018

STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 Daniel Atha & Brian Boom © 2018 The New York Botanical Garden All rights reserved ISBN 978-0-89327-955-4 Center for Conservation Strategy The New York Botanical Garden 2900 Southern Boulevard Bronx, NY 10458 All photos NYBG staff Citation: Atha, D. and B. Boom. 2018. State of New York City’s Plants 2018. Center for Conservation Strategy. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY. 132 pp. STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION 10 DOCUMENTING THE CITY’S PLANTS 10 The Flora of New York City 11 Rare Species 14 Focus on Specific Area 16 Botanical Spectacle: Summer Snow 18 CITIZEN SCIENCE 20 THREATS TO THE CITY’S PLANTS 24 NEW YORK STATE PROHIBITED AND REGULATED INVASIVE SPECIES FOUND IN NEW YORK CITY 26 LOOKING AHEAD 27 CONTRIBUTORS AND ACKNOWLEGMENTS 30 LITERATURE CITED 31 APPENDIX Checklist of the Spontaneous Vascular Plants of New York City 32 Ferns and Fern Allies 35 Gymnosperms 36 Nymphaeales and Magnoliids 37 Monocots 67 Dicots 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report, State of New York City’s Plants 2018, is the first rankings of rare, threatened, endangered, and extinct species of what is envisioned by the Center for Conservation Strategy known from New York City, and based on this compilation of The New York Botanical Garden as annual updates thirteen percent of the City’s flora is imperiled or extinct in New summarizing the status of the spontaneous plant species of the York City. five boroughs of New York City. This year’s report deals with the City’s vascular plants (ferns and fern allies, gymnosperms, We have begun the process of assessing conservation status and flowering plants), but in the future it is planned to phase in at the local level for all species. -

Survey of Euphorbiaceae Family in Kopergaon Tehsil Of

International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (IJHSS) ISSN (P): 2319–393X; ISSN (E): 2319–3948 Vol. 9, Issue 3, Apr–May 2020; 47–58 © IASET SURVEY OF EUPHORBIACEAE FAMILY IN KOPERGAONTEHSIL OF MAHARASHTRA Rahul Chine 1 & MukulBarwant 2 1Research Scholar, Department of Botany, Shri Sadguru Gangagir Maharaj Science College, Maharashtra, India 2Research Scholar, Department of Botany, Sanjivani Arts Commerce and Science College, Maharashtra, India ABSTRACT The survey of Family Euphorbiaceae from Kopargoantehshil is done. In this we first collection of different member of Family Euphorbiaceae from different region of Kopargoantehasil. An extensive and intensive survey at plants was carried out from village Pathare, Derde, Pohegoan, Kopergaon, Padhegaon, Apegoan during the were collected in flowering and fruiting period throughout the year done. During survey we determine 16 member of Euphorbiceae from Kopargoantehshil Then we decide characterization on the basis of habit, flowering character, leaf and fruit character with help of that character and using different literature we identified each and every member of Euphorbiaceae Species were identified with relevant information and documented in this paper with regard to their Botanical Name, family, Habitat, flowering Fruiting session and their medicinal value of some member of Euphorbiaceae that used in medicine respiratory disorder such as cough, asthama, bronchitis etc and some are toxic in nature due to their toxic latex that is showing itching reaction. KEYWORDS : Family Euphorbiaceae, Respiratory Ailment, Identification, Chracterization and Documentation Article History Received: 09 Apr 2020 | Revised: 10 Apr 2020 | Accepted: 18 Apr 2020 INTRODUCTION The Euphorbiaceae, the spurge family, is one of the complex large family of flowering plants of angiosperm with 334 genera and 8000 species in the worlds (Wurdack 2004). -

Antioxidant Potential of Selected Underutilized Fruit Crop Species Grown in Sri Lanka

DOI: http://doi.org/10.4038/tar.v30i3.8315 Tropical Agricultural Research Vol. 30 (3): 1 – 12 (2019) Antioxidant Potential of Selected Underutilized Fruit Crop Species Grown in Sri Lanka M.A.L.N. Mallawaarachchi, W.M.T. Madhujith1* and D.K.N.G. Pushpakumara2 Postgraduate Institute of Agriculture University of Peradeniya Sri Lanka ABSTRACT: Lyophilized aqueous extracts of four underutilized fruit species namely Diospyros discolor (Velvet apple), Pouteria campechiana (Lavulu/Canistel), Phylanthus acidus (Mal-Nelli/Star gooseberry) and Phyllanthus emblica (Nelli/Indian gooseberry) were investigated for the antioxidant potential (AP) by 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay, 2,2-azino-bis-3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid (ABTS) assay and ferrous reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay. Total phenolic content (TPC) and total monomeric anthocyanin content (TMAC) were determined by Folin-Ciocalteu’s colorimetric assay and pH differential method, respectively. Vitamin C (VitC) content of fresh fruit was evaluated titrimertically and expressed as mg of ascorbic acid in 100 g of fresh weight (FW). The TPC and TMAC were expressed as mg of gallic acid equivalents (GAE)/100g FW and mg of cyanodin-3-glucoside (C3G)/100g FW. The measured parameters differed significantly among four fruit species. The values ranged between 84.42 – 1939.70 mg GAE/100g FW, 10.41 – 55.64 mg C3G/100g FW, 0.067 – 310.63 mg FW/ml, 9 – 81.29%, 238.25 – 2891.57 2+ Fe mol/100g FW and 17.12 – 523.14 mg/100g FW for TPC, TMAC, IC50, RSA, FRAP and VitC, respectively. Phyllanthus emblica possessed highest values in all parameters while Phyllanthus acidus showed the lowest except in TPC. -

10. GLOCHIDION J. R. Forster & G. Forster, Char. Gen. Pl. 57. 1775, Nom. Cons

Fl. China 11: 193–202. 2008. 10. GLOCHIDION J. R. Forster & G. Forster, Char. Gen. Pl. 57. 1775, nom. cons. 算盘子属 suan pan zi shu Li Bingtao (李秉滔 Li Ping-tao); Michael G. Gilbert Agyneia Linnaeus; Bradleia Banks ex Gaertner [“Bradleja”]. Trees or shrubs, monoecious, rarely dioecious; indumentum of simple hairs, often absent. Leaves alternate, distichous, or spiral; stipules thick, mostly persistent; petiole short; leaf blade simple, margin entire, venation pinnate. Flowers axillary or supra-axillary, fascicled or in short cymes or umbels, proximal axils with male flowers, distal axils usually with female flowers, usually distinctly pedicellate. Male flowers: pedicels slender or almost absent; sepals 5 or 6, imbricate; petals absent; disk absent; stamens 3–8, connate into an oblong or ellipsoid column, shorter than sepals; anthers 2-locular, extrorse, linear, longitudinally dehiscent, connectives prolonged into an erect acumen; pistillode absent. Female flowers: pedicels stout and short or subsessile; sepals as in male, but slightly thicker; ovary globose, 3–15-locular; ovules 2 per locule; styles connate into a short, thick, cylindric column, apex lobed or toothed, rarely free. Fruit a capsule, globose or depressed globose, ± prominently longitudinally grooved, sunken at apex, dehiscent into 3–15 2-valved cocci when mature, rarely unlobed; exocarp leathery or papery; endocarp crustaceous; styles usually persistent. Seeds not strophiolate, hemispheric or laterally compressed; endosperm fleshy; cotyledon flattened. About 200 species: chiefly in tropical Asia, the Pacific islands, and Malaysia, a few in tropical America and Africa; 28 species (seven endemic, one introduced) in China. Glochidion is noteworthy for its pollination mechanism, which involves a symbiotic relationship with moths of the genus Epicephala closely paralleling that found in Yucca (Kato et al., Proc. -

Ethnobotanical Observations of Euphorbiaceae Species from Vidarbha Region, Maharashtra, India

Ethnobotanical Leaflets 14: 674-80, 2010. Ethnobotanical Observations of Euphorbiaceae Species from Vidarbha region, Maharashtra, India G. Phani Kumar* and Alka Chaturvedi# Defence Institute of High Altitude Research (DRDO), Leh-Ladakh, India #PGTD Botany, RTM Nagpur University, Nagpur, India *corresponding author: [email protected] Issued: 01 June, 2010 Abstract An attempt has been made to explore traditional medicinal knowledge of plant materials belonging to various genera of the Euphorbiaceae, readily available in Vidharbha region of Maharasthtra state. Ethnobotanical information were gathered through several visits, group discussions and cross checked with local medicine men. The study identified 7 species to cure skin diseases (such as itches, scabies); 5 species for antiseptic (including antibacterial); 4 species for diarrhoea; 3 species for dysentery, urinary infections, snake-bite and inflammations; 2 species for bone fracture/ dislocation, hair related problems, warts, fish poisons, night blindness, wounds/cuts/ burns, rheumatism, diabetes, jaundice, vomiting and insecticide; 1 species as laxative , viral fever and arthritis. The results are encouraging but thorough scientific scrutiny is absolutely necessary before being put into practice. Key words: Ethnopharmacology; Vidarbha region; Euphorbiaceae; ethnobotanical information. Introduction The medicinal properties of a plant are due to the presence of certain chemical constituents. These chemical constituents, responsible for the specific physiological action, in the plant, have in many cases been isolated, purified and identified as definite chemical compounds. Quite a large number of plants are known to be of medicinal use remain uninvestigated and this is particularly the case with the Indian flora. The use of plants in curing and healing is as old as man himself (Hedberg, 1987). -

Nuytsia the Journal of the Western Australian Herbarium 26: 149–166 Published Online 3 November 2015

R.L. Barrett & I.R.H. Telford, Two new species of Phyllanthus (Phyllanthaceae) 149 Nuytsia The journal of the Western Australian Herbarium 26: 149–166 Published online 3 November 2015 Two new species of Phyllanthus from northern Australia and notes on Phyllanthus, Sauropus and Synostemon (Phyllanthaceae) in Western Australia Russell L. Barrett1,2,3,5,6 and Ian R.H. Telford4 1Botanic Gardens and Parks Authority, Kings Park and Botanic Garden, West Perth, Western Australia 6005 2Western Australian Herbarium, Department of Parks and Wildlife, Locked Bag 104, Bentley Delivery Centre, Western Australia 6983 3School of Plant Biology, Faculty of Science, The University of Western Australia, Crawley, Western Australia 6009 4Botany, School of Environmental and Rural Science, University of New England, Armidale, New South Wales 2351 5Current address: Australian National Herbarium, Centre for Australian National Biodiversity Research, National Research Collections Australia, CSIRO, GPO Box 1600, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory 2601 6Corresponding author, email: [email protected] Abstract Barrett, R.L. & Telford, I.R.H. Two new species of Phyllanthus from northern Australia and notes on Phyllanthus, Sauropus and Synostemon (Phyllanthaceae) in Western Australia. Nuytsia 26: 149–166 (2015). Two new species of Phyllanthus L. are described, both included within P. subgen. Lysiandra F.Muell.; P. eremicus R.L.Barrett & I.Telford occurring in the Pilbara, Great Sandy Desert and southern Dampierland bioregions of Western Australia and the Tanami region of the Northern Territory, and P. hamelinii I.Telford & R.L.Barrett restricted to the Carnarvon bioregion, Western Australia. Both species have reasonably restricted or poorly known distributions and P. eremicus is of some conservation concern.