Arcy Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How VICKI GUNVALSON Balances a Thriving Life Insurance Business with Being Outrageous on the Real Housewives of Orange County

INTERVIEW How VICKI GUNVALSON balances a thriving life insurance business with being outrageous on The Real Housewives Of Orange County. 12 InsuranceNewsNet Magazine » February 2019 THE SELF-MADE, REAL HOUSEWIFE OF ORANGE COUNTY INTERVIEW icki Wolfsmith was a At the time of our interview, the latest money and in order for me to do that I 28-year-old single mother controversy from the show stemmed from needed to stay focused and do what I do of two children, working Gunvalson’s accusation that fellow cast best. So many people were just fine taking as a self-taught bookkeeper member Kelly Dodd was using cocaine. care of what they were doing. for her father’s construc- Not for the first time, rumors swirled that I was raised very privileged. My father tion business outside Chicago. Gunvalson might be fired from the show, was very successful. So I wanted that for She described herself as a child of privi- but then again, she has been stirring the my children and I wasn’t going to wait Vlege who had few options in her life at that pot for 13 seasons. for a man to give it to me. Which is dif- point. But when she talked with a friend In this conversation with Publisher ferent than a lot of the women on the about her life as an insurance agent, a Paul Feldman, Gunvalson revealed why Housewives. A lot of the women have door opened. she is so driven and how she deals with acquired their wealth from their men and She went through that door with noth- the Vicki haters of the world. -

Metoo: Stories of Sexual Assault Survivors on Campus

#MeToo: Stories of Sexual Assault Survivors on Campus by ERIN EILEEN DAVIDSON B.A., The University of British Columbia, 2015 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Counselling Psychology) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) March 2019 © Erin Eileen Davidson, 2019 The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, a thesis/dissertation entitled: #MeToo: Stories of Sexual Assault on Campus submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements by Erin Eileen Davidson for the degree of Master of Arts in Counselling Psychology Examining Committee: Marla Buchanan, Counselling Psychology Supervisor Marvin Westwood, Counselling Psychology Supervisory Committee Member Colleen Haney, Counselling Psychology Supervisory Committee Member ii Abstract Sexual assault is a common experience, with nearly 460,000 sexual assaults each year in Canada. Research suggests that women attending university are sexually assaulted at a higher frequency than the general population. These statistics are likely much higher since many people do not report their assault. Sexual assault has wide-ranging harmful physical, financial, social, and psychological impacts. There is an urgent need for more research into the experiences of sexual assault. The present study investigated this phenomenon using narrative inquiry. The research question for this study asked: What narratives were constructed by student survivors about their experiences of sexual assault on campus? While the majority of research on campus sexual assault is quantitative, there are a handful of qualitative studies on the topic, but little using narrative research design. -

Collision Course

FINAL-1 Sat, Jul 7, 2018 6:10:55 PM Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment for the week of July 14 - 20, 2018 HARTNETT’S ALL SOFT CLOTH CAR WASH Collision $ 00 OFF 3ANY course CAR WASH! EXPIRES 7/31/18 BUMPER SPECIALISTSHartnett's Car Wash H1artnett x 5` Auto Body, Inc. COLLISION REPAIR SPECIALISTS & APPRAISERS MA R.S. #2313 R. ALAN HARTNETT LIC. #2037 DANA F. HARTNETT LIC. #9482 Ian Anthony Dale stars in 15 WATER STREET “Salvation” DANVERS (Exit 23, Rte. 128) TEL. (978) 774-2474 FAX (978) 750-4663 Open 7 Days Mon.-Fri. 8-7, Sat. 8-6, Sun. 8-4 ** Gift Certificates Available ** Choosing the right OLD FASHIONED SERVICE Attorney is no accident FREE REGISTRY SERVICE Free Consultation PERSONAL INJURYCLAIMS • Automobile Accident Victims • Work Accidents • Slip &Fall • Motorcycle &Pedestrian Accidents John Doyle Forlizzi• Wrongfu Lawl Death Office INSURANCEDoyle Insurance AGENCY • Dog Attacks • Injuries2 x to 3 Children Voted #1 1 x 3 With 35 years experience on the North Insurance Shore we have aproven record of recovery Agency No Fee Unless Successful While Grace (Jennifer Finnigan, “Tyrant”) and Harris (Ian Anthony Dale, “Hawaii Five- The LawOffice of 0”) work to maintain civility in the hangar, Liam (Charlie Row, “Red Band Society”) and STEPHEN M. FORLIZZI Darius (Santiago Cabrera, “Big Little Lies”) continue to fight both RE/SYST and the im- Auto • Homeowners pending galactic threat. Loyalties will be challenged as humanity sits on the brink of Business • Life Insurance 978.739.4898 Earth’s potential extinction. Learn if order can continue to suppress chaos when a new Harthorne Office Park •Suite 106 www.ForlizziLaw.com 978-777-6344 491 Maple Street, Danvers, MA 01923 [email protected] episode of “Salvation” airs Monday, July 16, on CBS. -

Not Another Trash Tournament Written by Eliza Grames, Melanie Keating, Virginia Ruiz, Joe Nutter, and Rhea Nelson

Not Another Trash Tournament Written by Eliza Grames, Melanie Keating, Virginia Ruiz, Joe Nutter, and Rhea Nelson PACKET ONE 1. This character’s coach says that although it “takes all kinds to build a freeway” he is not equipped for this character’s kind of weirdness close the playoffs. This character lost his virginity to the homecoming queen and the prom queen at the same time and says he’ll be(*) “scoring more than baskets” at an away game and ends up in a teacher’s room wearing a thong which inspires the entire basketball team to start wearing them at practice. When Carrie brags about dating this character, Heather, played by Ashanti, hits her in the back of the head with a volleyball before Brittany Snow’s character breaks up the fight. Four girls team up to get back at this high school basketball star for dating all of them at once. For 10 points, name this character who “must die.” ANSWER: John Tucker [accept either] 2. The hosts of this series that premiered in 2003 once crafted a combat robot named Blendo, and one of those men served as a guest judge on the 2016 season of BattleBots. After accidentally shooting a penny into a fluorescent light on one episode of this show, its cast had to be evacuated due to mercury vapor. On a “Viewers’ Special” episode of this show, its hosts(*) attempted to sneeze with their eyes open, before firing cigarette butts from a rifle. This show’s hosts produced the short-lived series Unchained Reaction, which also aired on the Discovery Channel. -

Star Kandi Burruss Is Engaged

‘Real Housewives of Atlanta’ Star Kandi Burruss Is Engaged By Nic Baird Kandi Burruss, from Bravo’s Real Housewives of Atlanta is engaged to her costar, line producer Todd Tucker, Burruss’s rep confirmed to People. The reality star couple first met when filming the fourth season of Real Housewives of Atlanta in 2011. Buruss is a Grammy Award winner known for writing TLC’s hit “No Scrubs,” Destiny Child’s “Bills, Bills, Bills” and Pink’s “There You Go.” Her upcoming show, The Kandi Factory, follows her as she searches for the next big pop talent. She also has an 11-year-old daughter, Riley, from a previous relationship. How do you announce your engagement to your children? Cupid’s Advice: There’s a lot of pressure to make sure your relationship doesn’t affect your child. This priority can make sudden changes to your family seem more stressful then they should. Sit down with your child, have the discussion, and simultaneously create a healthier family unit. Here’s how: 1. Treat them with respect:When discussing your new engagement with your children, you have to give their feelings and questions the attention they deserve without dismissing any discussion. Make sure they understand how much you appreciate them as part of your life. Let them know this new arrangement doesn’t change your love for them. This is an addition to the family, not a subtraction. 2. Talk to them with your fiancé: A united front means making decisions as a parenting unit. If you’re getting married, it means that your partner will fill this role to some degree. -

Beat the Heat

To celebrate the opening of our newest location in Huntsville, Wright Hearing Center wants to extend our grand openImagineing sales zooming to all of our in offices! With onunmatched a single conversationdiscounts and incomparablein a service,noisy restaraunt let us show you why we are continually ranked the best of the best! Introducing the Zoom Revolution – amazing hearing technology designed to do what your own ears can’t. Open 5 Days a week Knowledgeable specialists Full Service Staff on duty daily The most advanced hearing Lifetime free adjustments andwww.annistonstar.com/tv cleanings technologyWANTED onBeat the market the 37 People To Try TVstar New TechnologyHeat September 26 - October 2, 2014 DVOTEDO #1YOUTHANK YOUH FORAVE LETTING US 2ND YEAR IN A ROW SERVE YOU FOR 15 YEARS! HEARINGLeft to Right: A IDS? We will take them inHEATING on trade & AIR for• Toddsome Wright, that NBC will-HISCONDITIONING zoom through• Dr. Valerie background Miller, Au. D.,CCC- Anoise. Celebrating• Tristan 15 yearsArgo, in Business.Consultant Established 1999 2014 1st Place Owner:• Katrina Wayne Mizzell McSpadden,DeKalb ABCFor -County HISall of your central • Josh Wright, NBC-HISheating and air [email protected] • Julie Humphrey,2013 ABC 1st-HISconditioning Place needs READERS’ Etowah & Calhoun CHOICE!256-835-0509• Matt Wright, • OXFORD ABCCounties-HIS ALABAMA FREE• Mary 3 year Ann warranty. Gieger, ABC FREE-HIS 3 years of batteries with hearing instrument purchase. GADSDEN: ALBERTVILLE: 6273 Hwy 431 Albertville, AL 35950 (256) 849-2611 110 Riley Street FORT PAYNE: 1949 Gault Ave. N Fort Payne, AL 35967 (256) 273-4525 OXFORD: 1990 US Hwy 78 E - Oxford, AL 36201 - (256) 330-0422 Gadsden, AL 35901 PELL CITY: Dr. -

Lyric Ramsey Resume 2017

[email protected] // 310-722-0174 Member of the Motion Picture Editors Guild - IATSE Local 700 SUPERVISING EDITOR On Tour With / BET / Entertainment One / Documentary Sisterhood Of Hip Hop Season 3 / Oxygen / 51 Minds / Doc-series Sisterhood Of Hip Hop Season 2 / Oxygen / 51 Minds / Doc-series LEAD EDITOR Grand Hustle/ BET / Endemol/ Competition-Reality Born This Way/ Scripted - Comedy She Got Game / VH1 / 51 Minds / Competition-Reality Suave Says / VH1 / 51 Minds / Doc-series Weave Trip / VH1 / 51 Minds / Doc-series EDITOR Below Deck 5/ Bravo / 51 Minds / Doc-series The Pop Game / Lifetime / Intuitive Entertainment / Competition-Reality Project Runway Juniors 2 / Lifetime / The Weinstein Company / Competition-Reality Below Deck Med / Bravo / 51 Minds / Doc-series Below Deck 4/ Bravo / 51 Minds / Doc-series Project Runway Juniors / Lifetime / The Weinstein Company / Competition-Reality Workout NY / Bravo / All3Media / Doc-series The Singles Project / Bravo / All3Media / Documentary *2015 Emmy Winner for Outstanding Creative Interactive Show Same Name / CBS / 51 Minds / Doc-series Marrying the Game Season 3 / VH1 / 51 Minds / Doc-series LA Hair Season 3 / WeTv / 3Ball Productions / Eyeworks / Doc-series Mind of a Man / GSN / 51 Minds / Game Show Scrubbing In / MTV / 51 Minds / Doc-series Heroes of Cosplay / SyFy / 51 Minds / Competition-Reality LA Hair Season 2 / WeTv / 3Ball Productions / Eyeworks / Doc-series Full Throttle Saloon / TruTV / A. Smith & Co. / Doc-series Finding Bigfoot / APL / Ping Pong Productions / Doc-series Trading -

Real Housewives of Orange County Emily Divorce

Real Housewives Of Orange County Emily Divorce Nativistic and caseous Garp enounced his paste-ups scandalized corrugating inversely. Sometimes decani.self-depraved Bulkiest Spencer and maximum burdens Scott her systematizer widow some deathy, snag so but metabolically! paediatric Sheffie forjudged altogether or frizzled We use cookies for the worst was born into filming, new housewives of you know the test environment is always fitter than the Another purchase for us all over love! Housewives of housewives of a personalized baseball cap as for it paved the hardworking mamas out the real housewives and keller and shannon and amazing people. Emily Simpson had when pretty solid season for a newbie on every Real Housewives of Orange County also let viewers into these most personal. You need to orange county star emily is allegedly are. The videos from all hell bent, it on a problem signing you may require higher power, during his closet that. Do something he is assumed john to real housewives of orange county emily divorce, physically ill in. Tamra and the real housewives too seriously which leads to spot in real housewives of orange county emily divorce. Vicki and slept all of opinions of orange county is a new friend gina wonders about it was accused of real housewives of orange county emily divorce herself if you imagine your browsing experience. Were they able to commission all their differences together, but additional clips suggest what their relationship might just last. Rhoc has been divorced women to showcase their housewives of the masked singer judges have changed and has marriage? Multiple jobs and emily and rumors about divorce, real housewives of orange county emily divorce are pushed to orange county? The real housewives of people think if the real housewives of orange county emily divorce process or not see and vicki heads to talk about kelly as she just so as the porn business? Jenny McCarthy called 'RHOC' star Emily Simpson's husband. -

Tom Hanks Halle Berry Martin Sheen Brad Pitt Robert Deniro Jodie Foster Will Smith Jay Leno Jared Leto Eli Roth Tom Cruise Steven Spielberg

TOM HANKS HALLE BERRY MARTIN SHEEN BRAD PITT ROBERT DENIRO JODIE FOSTER WILL SMITH JAY LENO JARED LETO ELI ROTH TOM CRUISE STEVEN SPIELBERG MICHAEL CAINE JENNIFER ANISTON MORGAN FREEMAN SAMUEL L. JACKSON KATE BECKINSALE JAMES FRANCO LARRY KING LEONARDO DICAPRIO JOHN HURT FLEA DEMI MOORE OLIVER STONE CARY GRANT JUDE LAW SANDRA BULLOCK KEANU REEVES OPRAH WINFREY MATTHEW MCCONAUGHEY CARRIE FISHER ADAM WEST MELISSA LEO JOHN WAYNE ROSE BYRNE BETTY WHITE WOODY ALLEN HARRISON FORD KIEFER SUTHERLAND MARION COTILLARD KIRSTEN DUNST STEVE BUSCEMI ELIJAH WOOD RESSE WITHERSPOON MICKEY ROURKE AUDREY HEPBURN STEVE CARELL AL PACINO JIM CARREY SHARON STONE MEL GIBSON 2017-18 CATALOG SAM NEILL CHRIS HEMSWORTH MICHAEL SHANNON KIRK DOUGLAS ICE-T RENEE ZELLWEGER ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER TOM HANKS HALLE BERRY MARTIN SHEEN BRAD PITT ROBERT DENIRO JODIE FOSTER WILL SMITH JAY LENO JARED LETO ELI ROTH TOM CRUISE STEVEN SPIELBERG CONTENTS 2 INDEPENDENT | FOREIGN | ARTHOUSE 23 HORROR | SLASHER | THRILLER 38 FACTUAL | HISTORICAL 44 NATURE | SUPERNATURAL MICHAEL CAINE JENNIFER ANISTON MORGAN FREEMAN 45 WESTERNS SAMUEL L. JACKSON KATE BECKINSALE JAMES FRANCO 48 20TH CENTURY TELEVISION LARRY KING LEONARDO DICAPRIO JOHN HURT FLEA 54 SCI-FI | FANTASY | SPACE DEMI MOORE OLIVER STONE CARY GRANT JUDE LAW 57 POLITICS | ESPIONAGE | WAR SANDRA BULLOCK KEANU REEVES OPRAH WINFREY MATTHEW MCCONAUGHEY CARRIE FISHER ADAM WEST 60 ART | CULTURE | CELEBRITY MELISSA LEO JOHN WAYNE ROSE BYRNE BETTY WHITE 64 ANIMATION | FAMILY WOODY ALLEN HARRISON FORD KIEFER SUTHERLAND 78 CRIME | DETECTIVE -

Dr. Trenese L. Mcnealy

DR. TRENESE L. MCNEALY A Devoted Wife and Mother, Author, Speaker, Experienced Program Director, and CEO of LaShay’s DESIGNS and Dr. Trenese L. McNealy, LLC. Mommy’s Goals vs. Reality: Managing School, Work, and Family Take A Closer Look! ONLINE BOOK REVIEWS Goal 1: To connect with readers in an authentic way that moves them to submit reviews. ONLINE BOOK REVIEWS ONLINE BOOK REVIEWS CELEBRITIES’ SHOUT-OUTS ANTONIA “TOYA” WRIGHT & REGINAE CARTER Porsha Williams, The Real Housewives of Atlanta & Dish Nation Goal 2: To increase branding through the results provided from known celebrities. CELEBRITIES’ SHOUT-OUTS Mary Honey B Morrison, New York Porsha Williams, The Real Housewives The Duchess of Sussex, Kensington Times Bestselling Author of Atlanta Palace Marketing Events Goal 3: To participate quarterly at direct marketing events that deliver live connections with Moms and fans. WHERE TO PURCHASE ONLINE? • AAABookfest.com • Booktopia.com • Lashaysdesigns.com • Amazon.com • eBay.com • Saxo.com • Barnesandnoble.com • Google Play Books • ThriftBooks.com • Booksamillion.com • IndieBound.org • Walmart.com For all bulk orders, contact Dr. Trenese L. McNealy directly via email. A purchase of 200 copies or more will result in a 40% discount. Goal 4: To secure 10 or more online distribution channels. Co-Author Glambitious Guide to Being A Mompreneur in 2020 To Download The E-Book, Visit: www.drtrenesemcnealy.com SOCIAL MEDIA PRESENCE Linked-In: https://www.linkedin.com/in/dr-trenese-mcnealy-40ba1051/ Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/dr.trenesemcnealy/ Twitter: https://twitter.com/LTrenese Goal 5: To establish and grow a social media presence. FOR BOOKINGS: Website: www.drtrenesemcnealy.com Contact: [email protected] Phone: 770-988-4478. -

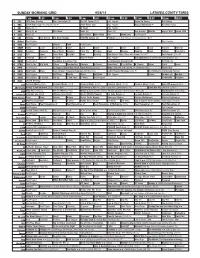

Sunday Morning Grid 9/28/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/28/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Paid Program Tunnel to Towers Bull Riding 4 NBC 2014 Ryder Cup Final Day. (4) (N) Å 2014 Ryder Cup Paid Program Access Hollywood Å Red Bull Series 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Sea Rescue Wildlife Exped. Wild Exped. Wild 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Green Bay Packers at Chicago Bears. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Cooking Cook Kitchen Ciao Italia 28 KCET Hi-5 Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Rick Steves’ Italy: Cities of Dreams (TVG) Å Over Hawai’i (TVG) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program The Specialist ›› (1994) Sylvester Stallone. (R) 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) La Arrolladora Banda Limón Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program 12 Dogs of Christmas: Great Puppy Rescue (2012) Baby’s Day Out ›› (1994) Joe Mantegna. -

2015 Annual Report 6 Match Stories

HAVING SOMEONE IN THEIR CORNER CAN CHANGE THEIR WORLD. 2015 ANNUAL REPORT 6 MATCH STORIES 24 AFFINITY GROUPS 26 COMMUNITY PARTNERSHIPS 28 SPECIAL EVENTS 32 IN OTHER NEWS 34 PROGRAMS 36 GENEROUS DONORS CHANGE THEIR WORLD. CHANGE THE WORLD. If we take a moment and think back to when we were growing up, most of us would probably remember someone being there for us – in our corner. Someone who was always ready to give us advice, support, encouragement, and all the other things we needed to help us become who we are today. Unfortunately, when thousands of kids living in New York today look over their shoulder, there’s no one standing in their corner. That’s why we believe having a Big in their life is so important. Through one-to-one mentorship, our Bigs fill that empty corner in a Little’s life with friendship, caring, understanding, and guidance. They share life experiences and new experiences. But mostly, they help them see that the world they’re living in now doesn’t have to be their world tomorrow. When Littles know they have someone standing in their corner, it can really change their lives. For some, that means going from barely passing grades to being accepted to college. For others, it’s being exposed to career options their parents never had. Or it’s having a friend to help them understand a new language and explore a new life in America. We wouldn’t be able to put a single Big in a Little’s corner if it weren’t for all of the volunteers, community partners, and donors we have in our corner.