Financial Inclusion: Lessons from Jordan and Lebanon.” Working Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Directory of Deposit Insurers

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation International Directory of Deposit Insurers September 2015 A listing of addresses of deposit insurers, central banks and other entities involved in deposit insurance functions. Division of Insurance and Research Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Washington, DC 20429 The FDIC wants to acknowledge the cooperation of all the countries listed, without which the directory’s compilation would not have been possible. Please direct any comments or corrections to: Donna Vogel Division of Insurance and Research, FDIC by phone +1 703 254 0937 or by e-mail [email protected] FDIC INTERNATIONAL DIRECTORY OF DEPOSIT INSURERS ■ SEPTEMBER 2015 2 Table of Contents AFGHANISTAN ......................................................................................................................................6 ALBANIA ...............................................................................................................................................6 ALGERIA ................................................................................................................................................6 ARGENTINA ..........................................................................................................................................6 ARMENIA ..............................................................................................................................................7 AUSTRALIA ............................................................................................................................................7 -

Humanitarian Cash Transfers and Financial Inclusion: Lessons from Jordan and Lebanon.” Working Paper

HUMANITARIAN CASH TRANSFERS AND FINANCIAL INCLUSION Lessons from Jordan and Lebanon April 2020 Nadine Chehade, Peter McConaghy, and Chrissy Martin Meier Acknowledgments This paper is the result of extensive research combining a literature review, multiple in-country visits, and desk-based analytical work. Data for the paper leveraged work led by Khurram Sikander and Tricia Cuna Weaver at Paysys Global, with support from Karim Jindani. It has been reviewed by Gregory C. Chen (Lead Financial Sector Specialist, CGAP), Matthew Soursourian and Yasmin Bin Human (Financial Sector Specialists, CGAP), and Karol Karpinski (Financial Sector Specialist, FCI). The team is also grateful for the inputs provided on earlier versions by Sophie Tholstrup and Julie Lawson McDowall at the Cash Learning Partnership (CaLP) and by Antoine Navarro (CGAP consultant). The research was supported by the State and Peace- Building Trust Fund, the World Bank Group’s largest global trust fund focused on supporting countries impacted by fragility, conflict, and violence. Consultative Group to Assist the Poor 1818 H Street, NW, MSN F3K-306 Washington, DC 20433 USA Internet: www.cgap.org Email: [email protected] Telephone: +1 202 473 9594 Cover photo by Tareq Khlaf, 2014 CGAP Photo Contest. © CGAP/World Bank, 2020. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). Under the Creative Commons Attribution license, you are free to copy, distribute, transmit, and adapt this work, including for commercial purposes, under the terms of this license. Attribution—Cite the work as follows: Chehade, Nadine, Peter McConaghy, and Chrissy Martin Meier. -

Jordan's Financial Sector Performance During the COVID-19

Jordan’s Financial Sector Performance During the COVID-19 Pandemic August 2020 Jordan’s Financial Sector Performance during the COVID-19 Pandemic – August 2020 1 يقوم منتدى اﻻستراتيجيات اﻷردني بمشاركة املعلومات اﻻقتصادية املهمة التي يتم تجميعها من مصادر محلية وعاملية مختلفة؛ وذلك بهدف نشر الوعي حول اﻷمور اﻻقتصادية واﻻجتماعية والتوعية في ظل التغييرات التي يشهدها العالم وذلك ملواكبة آخر التطورات وطرح مجال للتفكير في حلول تعمل على تنمية وتعزيز اﻻقتصاد الوطني. Jordan Strategy Forum shares important economic information that is collected from various local & international sources; with the aim of raising economic and social awareness. This is done in order to track the latest developments and suggest solutions that would develop and strengthen the national economy. Jordan’s Financial Sector Performance during the COVID-19 Pandemic – August 2020 2 On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic. Soon after, the swift and massive shock of COVID-19 and the various shutdown measures to contain it have plunged the global economy into a severe recession. Nevertheless, since the outbreak began, “more than 1,400 measures have been adopted to support the financial sector by more than 140 different countries” (World Bank). Indeed, the objectives of the adopted measures are to stabilize financial markets, and maintain the flow of credit and liquidity to the most affected sectors, especially small and medium enterprises, as well as households. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that global public debt (as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product / GDP) will increase by 18.7% compared to the 10.5% increase following the 2008 global financial crisis. -

Digital Finance Country Report Jordan

ANDREW MOORE / FLICKR DIGITAL FINANCE COUNTRY REPORT JORDAN DISCLAIMER: The USAID local enterprise support (LENS) project is funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and implemented by FHI 360. This report is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of MEDA and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States. ACKNOWLEGDEMENTS USAID Jordan Local Enterprise Support Project (LENS) would like to acknowledge the strong support of all key informants Interviewees Annex 2.This report was drafted by Peter Nzebile and Davy Denadi. Further, reviews from Chris Statham and Caroline Averch (USAID LENS) and Imad Aloyoun (Dinarak) were invaluable. This document has been produced with the financial assistance of USAID LENS. The views expressed herein can in no way be taken to reflect the official opinion of USAID. 1 | DIGITAL FINANCE COUNTRY REPORT- JORDAN TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................. 1 TABLE OF TABLES .................................................................................................................... 3 TABLE OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................. 3 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS .......................................................................... 3 -

The Jordan DFS Landscape – a Situation Analysis

The Jordan DFS Landscape – A Situation Analysis Will the mandating of “basic bank accounts” by the Central Bank of Jordan to commercial banks, usher in strategic partnerships between banks, MicroFinance Institutions and Payment Service Providers? 5th March 2019 Chris Statham DFS and MFI consultant Email: [email protected] LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/mobilemoneyconsultant LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ACC Agricultural Credit Corporation AML Anti-Money Laundering API Application Programme Interfaces ATM Automated Teller Machine CBJ Central Bank of Jordan CBS Core Banking Software CGAP Consultative Group to Assist the Poor DEF Development and Employment Fund EFT Electronic Funds Transfer EMPS Emerging Markets Payments FSP Financial Service Provider GDP Gross Domestic Product Jo-PACC Jordan Payments and Clearing Company KYC Know-Your-Customer MCF Military Credit Fund MEPS Middle East Payment Services MfW Microfund for Women MFI Microfinance Institution NFIS National Financial Inclusion Strategy OTC Over –the-counter P2G Person to Government P2P Person-to-Person (transfer) PSP Payment Service Provider RTGS Real Time Gross Settlement USAID U.S. Agency for International Development List of Abbreviations and Acronyms ............................................................................................... 2 1. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................. 4 2. Situation Analysis .................................................................................................................... -

Microfinance in Jordan: Developments, Challenges, and Future Prospects

Microfinance in JORDAN Developments, Challenges and Future Prospects MICROFINANCE IN JORDAN Developments, Challenges and Future Prospects DISCLAIMER The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of International Finance Corporation or the Executive Directors of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank or the governments they represent. IFC does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. All data on microfinance institutions in this report, unless otherwise stated, have been provided and reviewed by the institutions themselves through Tanmeyah. Table of Contents ABBREVIATIONS & ACRONYMS ................................................................................................................. v FOREWORD .............................................................................................................................................vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENT .............................................................................................................................vii NOTE TO THE READER .............................................................................................................................vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................... 1 1. INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................................................3 -

Jordan Report

JordanEconomicReport NO FISCAL ROOM FOR EXPANSIONARY SPENDING POLICIES Economy slowing down amid regional turmoil: The Jordanian economy is reporting a net activity slowdown amid the spillover effects of the regional unrest. Although Jordan does not share the regional political characteristics behind turmoil in MENA countries in general, it does share the tough economic, demographic and social conditions of the countries under turmoil. The IMF has revised the Kingdom’s real May growth for 2011 to 3.3%, keeping the economy within the range of low economic growth for the third year in a row after it had reported a streak of high growth of 8% on average between 2003 and 2008. 2011 Real sector indicators reporting mixed performances: Among rising real sector indicators year-to-date, power production was up by 8.1%, merchandise at the Aqaba Port rose by 18.5%, real estate sales surged by 24% and construction permits grew by 28.0%. On the downside however, cement production fell by 15.1%, the number of tourists dropped by a yearly 5.5% and cleared checks, an indicator of both consumption and investment spending demand, contracted by 4.3% driving a 13.1% drop in velocity of money. Jordan’s foreign trade adversely impacted: The contraction of Jordanian exports to Syria, Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Yemen and Bahrain that witnessed political and security troubles was offset by a rise in Jordan’s exports to Iraq which continues to retain the lion’s share of Jordanian exports. On the import side however, Jordan’s import bill is apt to be significantly affected by the rise in oil prices. -

Why Did the Central Bank of Jordan Put Policies for Financial Inclusion in Place?

Case Study: Why did the Central Bank of Jordan put Policies for Financial Inclusion in Place? Submitted by Mona Ghassan Halasa Capstone Adviser Kimberley Wilson Lecturer, International Business and Human Security International Relations Master of Arts Capstone Project Fletcher School for Law and Diplomacy Tufts University April 16, 2018 © YEAR AUTHOR http://fletcher.tufts.edu Contents Abbreviations, Acronyms and Glossary ......................................................................................... 4 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Background ..................................................................................................................................... 7 On the Global Scene .................................................................................................................... 7 On the Local Jordanian Scene ..................................................................................................... 8 Financial Inclusion and Development ............................................................................................ 9 What is Financial Inclusion? ....................................................................................................... 9 Why is Financial Inclusion Important? ..................................................................................... 10 What is the Link between Financial Inclusion and Development? .......................................... -

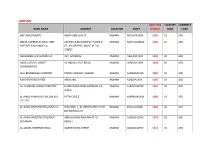

Jordan Bank Nbr Country Currency Bank Name Address Location Swift Dummy Code Code

JORDAN BANK NBR COUNTRY CURRENCY BANK NAME ADDRESS LOCATION SWIFT DUMMY CODE CODE ABC INVESTMENTS RANIA ABDULLA ST AMMAN ABCVJOA1XXX 1001 JO JOD ABDUL KAREEM AL-RAWI AND ALFAISLYA BUILDING 67, FLOOR 1: AMMAN RAWIJOAMXXX 1002 JO JOD PARTNER EXCHANGE CO 67, ALGARDENZ, WASFI AL TAL STREET ABUSHEIKHA EXCHANGE LLC 133, GARDENS AMMAN ABXLJOAAXXX 1003 JO JOD AGRICULTURAL CREDIT AL-ABDALI: SALT ROAD AMMAN ACRCJOA1XXX 1004 JO JOD CORPORATION AHLI BROKERAGE COMPANY PRINCE ZAID BIN: SHAKER AMMAN AHBOJOA1XXX 1005 JO JOD AJIAD FOR SECURITIES ABDOUN1 AMMAN AJSEJOA1XXX 1006 JO JOD AL ALAMI EXCHANGE COMPANY HADDAD BUILDING GARDENS: 51, AMMAN ALEYJOAMXXX 1007 JO JOD STREET AL AMAL FINANCIAL INVESMENTS FIFTH CIRCLE AMMAN AMFNJOA1XXX 1008 JO JOD CO. LTD AL ARABI INVESTMENT GROUP CO. BUILDING: 1, AL-RABIEH ABDULLAH AMMAN ATIGJOA1XXX 1009 JO JOD BIN RAWAHA ST. AL ARABI INVESTMENT GROUP ABDALLA BIN: RAWAHA ST AL AMMAN AIGMJOA1XXX 1010 JO JOD COMPANY RABIEH AL AWAEL INTERNATIONAL QUEEN RANIA STREET AMMAN AWAIJOA1XXX 1011 JO JOD BANK NBR COUNTRY CURRENCY BANK NAME ADDRESS LOCATION SWIFT DUMMY CODE CODE AL FARES FOR FINANCIAL INVEST CO AMMAN STREET IRBID FRRSJOA1XXX 1012 JO JOD AL MAWARED FOR BROKERAGE ISSAM AL AMMAN MBRCJOA1XXX 1013 JO JOD COMPANY AL RAJHI BANK, JORDAN BRANCH 999, JABAL AMMAN AMMAN RJHIJOAMXXX 1014 JO JOD AL WAMEEDH FOR FINANCIAL UM AMMAN WFSIJOA1XXX 1015 JO JOD SERVICES AND INVESTMENT AL-AULA FINANCIAL INVESTMENTS NOUR ST AMMAN ALNTJOA1XXX 1016 JO JOD ALAWNEH EXCHANGE L.L.C 15, ABDULHAMID SHOMAN STR AMMAN ALELJOAMXXX 1017 JO JOD AL-BILAD FOR -

Covid-19 Report English.Pdf

LOCKDOWN BUT NOT SHUTDOWN THE IMPACT OF THE COVID-1-199 PANDEMIANDEMICC ON FINANCIAL SERVICES IN JORDAN -OCTOBER 2020- Authors: Dina AlSalhi, Enas Halaiqah, Jude Najjar, Leen Hashem and Moayad Ghannam Foreword by H.E Dr. Ziad Fariz - Chairman of the Board of Directors of JoPACC Jordan’s infrastructure has been developing and evolving over the years to better cater for the needs of the financial sector and the Jordanian economy. That being said, past crises that we dealt with have been largely socio-economic in nature. This allowed the Central Bank better control in mitigating the source of the impact. However, COVID-19 is primarily a health crisis that had economic implications. Furthermore, it was indiscriminatory of social, cultural, economic, or geographical considerations. Unlike our past experiences, the scale that we were encountering was a fully national scale. That complicated things, as the Central Bank could not mitigate the source of the crisis, but only its effects. Therefore, this represented a significant challenge that certainly required employing past experiences. However, it also necessitated problem solving and innovative problem thinking that took into consideration the entirety of Jordan’s economy. Naturally, we are experiencing unavoidable negative economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic which will spill into the short, medium, and long terms. A rise in unemployment, and subsequent decrease in consumption will exert significant pressures on Jordan’s business environment. The services sector, which accounts for over 60% of Jordan’s GDP, suffered substantially. The aforementioned is expected to increase uncertainty with regard to investments. That being said, we are witnessing a drastic change across business environments, which will result in higher demand for digital services, products, and operations. -

Business and Politics in the Muslim World Asia Report

BUSINESS AND POLITICS IN THE MUSLIM WORLD ASIA REPORT First Quarter 2009 Volume: 3 Reports of March, 2009 Table of contents Reports for the month of March Week-1 March 04, 2009 03 Week-2 March 11, 2009 57 Week-3 March 18, 2009 169 Week-4 March 25, 2009 366 Country profiles Sources 2 BUSINESS AND POLITICS IN THE MUSLIM WORLD ASIA REPORT March 4, 2009 Nadia Tasleem: Report on Asia 04 Ashia Rehman: Report on Fertile Crescent 13 3 BUSINESS AND POLITICS IN THE MUSLIM WORLD SOUTH & EAST ASIA and GCC & Fertile Crescent Nadia Tasleem Weekly Report from 21 February 2009 to 27 February 2009 Presentation: 4 March 2009 This report is based on the review of news items focusing on political, economic, social and geo-strategic developments in various regions namely; South Asia, East Asia, Fertile Crescent and GCC from 21 February 2009 to 27 February 2009 as have been collected by interns. Summary South Asia: Political Front: Government in Bangladesh seems to be struggling for the betterment of their country. In this regard various developments have been observed. Firstly new President Zillur Rahman expressed his desire to work neutrally for the welfare of his countrymen, on the eve of his oath taking as the country's 19th president. Secondly, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has announced to publish white papers on corruption. BNP Vice-chairman and lawmaker MK Anwar welcomed Prime Minister's idea and at the same time called upon the government not to restrain politicians in the name of curbing corruption. Government meanwhile has allowed all politicians to submit application at scrutiny panel for the cancellation of cases being filed against them to bring political harassment. -

Atms) in Jordan

International Journal of Business and Social Science Vol. 3 No. 9; May 2012 Customers’ Financial Needs satisfaction and Self-service Technology Banking: The Case of Automatic Teller Machines (ATMs) in Jordan Fawzi Al Sawalqa Accounting Department; Financial & Administrative Sciences Faculty Tafila Technical University Tafila-Jordan Abstract This study was conducted to achieve two main objectives. Firstly it assesses the effect of low cost services, security and privacy and ease of use on customers’ financial needs satisfaction of Automatic Teller Machines (ATMs). The study also assesses if there is a difference in customers’ financial needs satisfaction due to gender, age or academic qualification. Based on survey responses from 132 users, the results indicate that only privacy and security contributes significantly to the customers’ financial needs satisfaction. The results also revealed that the demographic characteristics of users make no difference in the financial needs satisfaction of ATMs users. An important implication of this study is that the results of it brought with them the need for Jordanian banks to put more emphasis on the different aspects of privacy and security, to decrease or remove the cost of ATMs usage and to introduce a good training to ATMs users. Keywords: ATMs, technological innovations, customers’ financial needs satisfaction, low cost service, privacy and security, ease of use, Jordan 1. Introduction ATMs are almost classified as new technology in context of developing country. ATMs introduced to markets since the 1970s (Mauldin, Sutherland & Hofmeister, 1978). ATMs can offer significant benefits to both banks and customers. By using ATMs, customers can deposit or withdraw cash, transfer funds from one account to another, inquire about account balance and request for cheque books and account statement (Liao, Shao, Wang & Chen, 1999; Karamala & Anchula, 2011).