Stephen Sondheim and His Filmic Influences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996 Stage by Stage The Development of the National Theatre from 1848 Designed by Michael Mayhew Compiled by Lyn Haill & Stephen Wood With thanks to Richard Mangan and The Mander & Mitchenson Theatre Collection, Monica Sollash and The Theatre Museum The majority of the photographs in the exhibition were commissioned by the National Theatre and are part of its archive The exhibition was funded by The Royal National Theatre Foundation Richard Eyre. Photograph by John Haynes. 1988 To mark the company’s 25th birthday in Peter Hall’s last year as Director of the National October, The Queen approves the title ‘Royal’ Theatre. He stages three late Shakespeare for the National Theatre, and attends an plays (The Tempest, The Winter’s Tale, and anniversary gala in the Olivier. Cymbeline) in the Cottesloe then in the Olivier, and leaves to start his own company in the The funds raised are to set up a National West End. Theatre Endowment Fund. Lord Rayne retires as Chairman of the Board and is succeeded ‘This building in solid concrete will be here by the Lady Soames, daughter of Winston for ever and ever, whatever successive Churchill. governments can do to muck it up. The place exists as a necessary part of the cultural scene Prince Charles, in a TV documentary on of this country.’ Peter Hall architecture, describes the National as ‘a way of building a nuclear power station in the September: Richard Eyre takes over as Director middle of London without anyone objecting’. of the National. 1989 Alan Bennett’s Single Spies, consisting of two A series of co-productions with regional short plays, contains the first representation on companies begins with Tony Harrison’s version the British stage of a living monarch, in a scene of Molière’s The Misanthrope, presented with in which Sir Anthony Blunt has a discussion Bristol Old Vic and directed by its artistic with ‘HMQ’. -

Sarah Mills Bacha 614.563.1066 Andrew Lloyd Webber's

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 22, 2018 Contact: Sarah Mills Bacha 614.563.1066 Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Aspects of Love at CATCO May 30-June 17 Chamber musical by one of musical theatre’s legends explores the many forms of love Love takes many forms – love between couples; romantic infatuation; the devotion of married people; and the ties of children to their parents. This chamber musical, written by one of contemporary musical theatre’s icons, Andrew Lloyd Webber, who gave us beloved classics, such as Phantom of the Opera and Evita, examines all of them. “Love Changes Everything” is the theme song of this musical first produced in 1989 in London and based upon a 1955 novella written by David Garnett, and “nothing in the world will ever be the same.” Aspects of Love, with book and music by Webber and lyrics by Don Black and Charles Hart, is presented through special arrangement with R&H Theatricals: www.rnh.com “Aspects of Love is one of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s lesser known works because it was produced after his blockbuster works of the 1970s and 1980s, but it is no less memorable with beautiful romantic lyrics and music, hallmarks of Webber musicals,” said Steven C. Anderson, CATCO producing director, who will direct CATCO’s chamber production. “If you loved the music of Phantom of the Opera, Cats and Evita and other works by Webber, you won’t want to miss CATCO’s presentation of Aspects of Love,” Anderson, said. CATCO will perform Aspects of Love, May 30-June 17, 2018, in the Studio One Theatre at the Vern Riffe Center, 77 S. -

The-Music-Of-Andrew-Lloyd-Webber Programme.Pdf

Photograph: Yash Rao We’re thrilled to welcome you safely back to Curve for production, in particular Team Curve and Associate this very special Made at Curve concert production of Director Lee Proud, who has been instrumental in The Music of Andrew Lloyd Webber. bringing this show to life. Over the course of his astonishing career, Andrew It’s a joy to welcome Curve Youth and Community has brought to life countless incredible characters Company (CYCC) members back to our stage. Young and stories with his thrilling music, bringing the joy of people are the beating heart of Curve and after such MUSIC BY theatre to millions of people across the world. In the a long time away from the building, it’s wonderful to ANDREW LLOYD WEBBER last 15 months, Andrew has been at the forefront of have them back and part of this production. Guiding conversations surrounding the importance of theatre, our young ensemble with movement direction is our fighting for the survival of our industry and we are Curve Associate Mel Knott and we’re also thrilled CYCC LYRICS BY indebted to him for his tireless advocacy and also for alumna Alyshia Dhakk joins us to perform Pie Jesu, in TIM RICE, DON BLACK, CHARLES HART, CHRISTOPHER HAMPTON, this gift of a show, celebrating musical theatre, artists memory of all those we have lost to the pandemic. GLENN SLATER, DAVID ZIPPEL, RICHARD STILGOE AND JIM STEINMAN and our brilliant, resilient city. Known for its longstanding Through reopening our theatre we are not only able to appreciation of musicals, Leicester plays a key role make live work once more and employ 100s of freelance in this production through Andrew’s pre-recorded DIRECTED BY theatre workers, but we are also able to play an active scenes, filmed on-location in and around Curve by our role in helping our city begin to recover from the impact NIKOLAI FOSTER colleagues at Crosscut Media. -

Scanned Using Scannx OS15000 PC

OHIO NEWS BUREAU INC. CLEVELAND, OHIO 44115 216/241-0675 COLUMBUS DISPBTCH COLUMBUS, OH, HM CIRC, 284,796 flPR-30-99 ^Night Music’ at ^^lOtterbein a lavish, lovely production By Midiael Grossberg Dispatch Theater Critic Shimmering with beauty, melody Theater review wit, A Little Night Music be A UWb NlgM HibIc, Otterbein comes a jeweled music box in the College's student production of deft hands of Otterbein College’s composer-lyricist Stephen Sondheim theater and music departments. ard author Hugh Wheeler’s musical. ' Lavish but unerringly tasteful, Directed by Dennis Romer. lovely but not gaudy, comically .................. Allison Sattinger broad but often delightfully subtle, Madame Armfeldt..... ...... Unda Dorff. the 'co-production ranks with Otter- Fredrik Egeiman ........Christopher Sloan'7 heir’s best spring musicals. Anne Egerman------ Ainanda Wheeler} ■ ■ Night Music is one of the most Cart-Magnus... .............. .Ayler Evan', ■challenging Stephen Sondheim Charlotte...... —... chrisi Carter ij “shows. Yet, Otterbein brings the ™ta............ ........... .... Jen Minter ,1973 Tony winner for best musical to Hennk................ Matthew DeVrienrt ^ftering life with grace, sophistica tion md seemingly effortless ease. Send In the bouquets - ..Director Dennis Romer and music Being performed at 8 tonight and ; director Kevin Purcell enhance the Saturday and 2 p.m. Sunday—and 7 wistful romanticism of Sondheim’s 8 p.m. May 6-8—in Cowan Hall, 30 ■< gorgeous score and author Hugh S. Grove Westerville. if. ,\yheeler’s portrait -

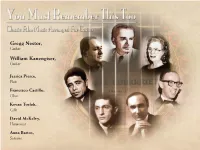

Gregg Nestor, William Kanengiser

Gregg Nestor, Guitar William Kanengiser, Guitar Jessica Pierce, Flute Francisco Castillo, Oboe Kevan Torfeh, Cello David McKelvy, Harmonica Anna Bartos, Soprano Executive Album Producers for BSX Records: Ford A. Thaxton and Mark Banning Album Produced by Gregg Nestor Guitar Arrangements by Gregg Nestor Tracks 1-5 and 12-16 Recorded at Penguin Recording, Eagle Rock, CA Engineer: John Strother Tracks 6-11 Recorded at Villa di Fontani, Lake View Terrace, CA Engineers: Jonathan Marcus, Benjamin Maas Digitally Edited and Mastered by Jonathan Marcus, Orpharian Recordings Album Art Direction: Mark Banning Mr. Nestor’s Guitars by Martin Fleeson, 1981 José Ramirez, 1984 & Sérgio Abreu, 1993 Mr. Kanengiser’s Guitar by Miguel Rodriguez, 1977 Special Thanks to the composer’s estates for access to the original scores for this project. BSX Records wishes to thank Gregg Nestor, Jon Burlingame, Mike Joffe and Frank K. DeWald for his invaluable contribution and oversight to the accuracy of the CD booklet. For Ilaine Pollack well-tempered instrument - cannot be tuned for all keys assuredness of its melody foreshadow the seriousness simultaneously, each key change was recorded by the with which this “concert composer” would approach duo sectionally, then combined. Virtuosic glissando and film. pizzicato effects complement Gold's main theme, a jaunty, kaleidoscopic waltz whose suggestion of a Like Korngold, Miklós Rózsa found inspiration in later merry-go-round is purely intentional. years by uniting both sides of his “Double Life” – the title of his autobiography – in a concert work inspired by his The fanfare-like opening of Alfred Newman’s ALL film music. Just as Korngold had incorporated themes ABOUT EVE (1950), adapted from the main title, pulls us from Warner Bros. -

Digital Commons @ Otterbein Nine

Otterbein University Digital Commons @ Otterbein 2008-2009 Season Productions 2001-2010 5-21-2009 Nine Otterbein University Theatre and Dance Department Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.otterbein.edu/production_2008-2009 Part of the Acting Commons, Dance Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Otterbein University Theatre and Dance Department, "Nine" (2009). 2008-2009 Season. 4. https://digitalcommons.otterbein.edu/production_2008-2009/4 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Productions 2001-2010 at Digital Commons @ Otterbein. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2008-2009 Season by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Otterbein. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OTTERBEIN COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF THEATRE AND DANCE AND DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC Present Nine Book by ARTHUR KOPIT Music & Lyrics by MAURY YESTON Adaptation from the Italian by Mario Fratti Broadway Production Directed by Tommy Tune Original Cast Album on Columbia Records & Tapes Directed by CHRISTINA KIRK Music Director DENNIS DAVENPORT Choreographer STELLA HIATT-KANE Set Design Costume Design ROB JOHNSON MARCIA HAIN Lighting Design DANA L. WHITE Stage Managed by KELSEY FARRIS May 21-24, 28-30, 2009 Fritsche Theatre at Cowan Hall Produced by special arrangement with SAMUEL FRENCH, INC. cast Guido............................................................................................. Cesar Villavicencio Young Guido..........................................................................................Conner -

Belvoir Terrace Staff 2018

Belvoir Terrace Staff 2018 Belvoir Terrace Staff 2018 Diane Goldberg Marcus - Director Educational Background D.M.A. City University of New York M.M. The Juilliard School B.M. Oberlin Conservatory Teaching/Working Experience American Camping Association Accreditation Visitor Private Studio Teacher - New York, NY Piano Instructor - Hunter College, New York, NY Vocal Coach Assistant - Hunter College, New York, NY Chamber Music Coach - Idyllwild School of Music, CA Substitute Chamber Music Coach - Juilliard Pre-College Division Awards/Publications/Exhibitions/Performances/Affiliations Married to Michael Marcus, Owner/Director of Camp Greylock, boys camp Becket, MA Independent School Liaison - Parents In Action, NYC Health & Parenting Association Coordinator - Trinity School, NYC American Camping Association Accreditation Visitor D.M.A. Dissertation: Piano Pedagogy in New York: Interviews with Four Master Teachers (Interviews with Herbert Stessin, Martin Canin, Gilbert Kalish, and Arkady Aronov) Teaching Fellowship - The City University of New York Honorary Scholarship for the Masters of Music Program – The Juilliard School The John N. Stern Scholarship - Aspen Music Festival Various Performances at: Paul Hall - Juilliard - New York Alice Tully Hall - New York City College - New York Berkshire Performing Arts Center, National Music Center - Lenox, MA WGBH Radio - Boston Reading Musical Foundation Museum Concert Series - Reading, PA Cancer Care Benefit Concert - Princeton, NJ Nancy Goldberg - Director Educational Background M.A. Harvard University -

BBC Four Programme Information

SOUND OF CINEMA: THE MUSIC THAT MADE THE MOVIES BBC Four Programme Information Neil Brand presenter and composer said, “It's so fantastic that the BBC, the biggest producer of music content, is showing how music works for films this autumn with Sound of Cinema. Film scores demand an extraordinary degree of both musicianship and dramatic understanding on the part of their composers. Whilst creating potent, original music to synchronise exactly with the images, composers are also making that music as discreet, accessible and communicative as possible, so that it can speak to each and every one of us. Film music demands the highest standards of its composers, the insight to 'see' what is needed and come up with something new and original. With my series and the other content across the BBC’s Sound of Cinema season I hope that people will hear more in their movies than they ever thought possible.” Part 1: The Big Score In the first episode of a new series celebrating film music for BBC Four as part of a wider Sound of Cinema Season on the BBC, Neil Brand explores how the classic orchestral film score emerged and why it’s still going strong today. Neil begins by analysing John Barry's title music for the 1965 thriller The Ipcress File. Demonstrating how Barry incorporated the sounds of east European instruments and even a coffee grinder to capture a down at heel Cold War feel, Neil highlights how a great composer can add a whole new dimension to film. Music has been inextricably linked with cinema even since the days of the "silent era", when movie houses employed accompanists ranging from pianists to small orchestras. -

The Enduring Power of Musical Theatre Curated by Thom Allison

THE ENDURING POWER OF MUSICAL THEATRE CURATED BY THOM ALLISON PRODUCTION SUPPORT IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY NONA MACDONALD HEASLIP PRODUCTION CO-SPONSOR LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Welcome to the Stratford Festival. It is a great privilege to gather and share stories on this beautiful territory, which has been the site of human activity — and therefore storytelling — for many thousands of years. We wish to honour the ancestral guardians of this land and its waterways: the Anishinaabe, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, the Wendat, and the Attiwonderonk. Today many Indigenous peoples continue to call this land home and act as its stewards, and this responsibility extends to all peoples, to share and care for this land for generations to come. CURATED AND DIRECTED BY THOM ALLISON THE SINGERS ALANA HIBBERT GABRIELLE JONES EVANGELIA KAMBITES MARK UHRE THE BAND CONDUCTOR, KEYBOARD ACOUSTIC BASS, ELECTRIC BASS, LAURA BURTON ORCHESTRA SUPERVISOR MICHAEL McCLENNAN CELLO, ACOUSTIC GUITAR, ELECTRIC GUITAR DRUM KIT GEORGE MEANWELL DAVID CAMPION The videotaping or other video or audio recording of this production is strictly prohibited. A MESSAGE FROM OUR ARTISTIC DIRECTOR WORLDS WITHOUT WALLS Two young people are in love. They’re next- cocoon, and now it’s time to emerge in a door neighbours, but their families don’t get blaze of new colour, with lively, searching on. So they’re not allowed to meet: all they work that deals with profound questions and can do is whisper sweet nothings to each prompts us to think and see in new ways. other through a small gap in the garden wall between them. Eventually, they plan to While I do intend to program in future run off together – but on the night of their seasons all the plays we’d planned to elopement, a terrible accident of fate impels present in 2020, I also know we can’t just them both to take their own lives. -

American Music Research Center Journal

AMERICAN MUSIC RESEARCH CENTER JOURNAL Volume 19 2010 Paul Laird, Guest Co-editor Graham Wood, Guest Co-editor Thomas L. Riis, Editor-in-Chief American Music Research Center College of Music University of Colorado Boulder THE AMERICAN MUSIC RESEARCH CENTER Thomas L. Riis, Director Laurie J. Sampsel, Curator Eric J. Harbeson, Archivist Sister Mary Dominic Ray, O.P. (1913–1994), Founder Karl Kroeger, Archivist Emeritus William Kearns, Senior Fellow Daniel Sher, Dean, College of Music William S. Farley, Research Assistant, 2009–2010 K. Dawn Grapes, Research Assistant, 2009–2011 EDITORIAL BOARD C. F. Alan Cass Kip Lornell Susan Cook Portia Maultsby Robert R. Fink Tom C. Owens William Kearns Katherine Preston Karl Kroeger Jessica Sternfeld Paul Laird Joanne Swenson-Eldridge Victoria Lindsay Levine Graham Wood The American Music Research Center Journal is published annually. Subscription rate is $25.00 per issue ($28.00 outside the U.S. and Canada). Please address all inquiries to Lisa Bailey, American Music Research Center, 288 UCB, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309-0288. E-mail: [email protected] The American Music Research Center website address is www.amrccolorado.org ISSN 1058-3572 © 2010 by the Board of Regents of the University of Colorado INFORMATION FOR AUTHORS The American Music Research Center Journal is dedicated to publishing articles of general interest about American music, particularly in subject areas relevant to its collections. We welcome submission of articles and pro- posals from the scholarly community, ranging from 3,000 to 10,000 words (excluding notes). All articles should be addressed to Thomas L. Riis, College of Music, University of Colorado Boulder, 301 UCB, Boulder, CO 80309-0301. -

Student Guide Table of Contents

GOODSPEED MUSICALS STUDENT GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS APRIL 13 - JUNE 21, 2018 THE GOODSPEED Production History.................................................................................................................................................................................3 Synopsis.......................................................................................................................................................................................................4 Characters......................................................................................................................................................................................................5 Meet the Writers.....................................................................................................................................................................................6 Meet the Creative Team........................................................................................................................................................................8 Presents for Mrs. Rogers......................................................................................................................................................................9 Will Rogers..............................................................................................................................................................................................11 Wiley Post, Aviation Marvel..............................................................................................................................................................16 -

The Wicker Husband Education Pack

EDUCATION PACK 1 1 Contents Introduction Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Section 1: The Watermill’s Production of The Wicker Husband ........................................................................ 4 A Brief Synopsis.................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Character Profiles…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………....…8 Note from the Writer…………………………………………..………………………..…….……………………………..…………….10 Interview with the Director ………………………….……………………………………………………………………..………….. 13 Section 2: Behind the Scenes of The Watermill’s The Wicker Husband …………………………………..… ...... 15 Meet the Cast ................................................................................................................................................................... 16 An Interview with The Musical Director .................................................................................................................. .20 The Design Process ......................................................................................................................................................... 21 The Wicker Husband Costume Design ...................................................................................................................... 23 Be a Costume Designer……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..25