UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Columbia Chronicle (05/21/2001) Columbia College Chicago

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago Columbia Chronicle College Publications 5-21-2001 Columbia Chronicle (05/21/2001) Columbia College Chicago Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cadc_chronicle Part of the Journalism Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Columbia College Chicago, "Columbia Chronicle (05/21/2001)" (May 21, 2001). Columbia Chronicle, College Publications, College Archives & Special Collections, Columbia College Chicago. http://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cadc_chronicle/514 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the College Publications at Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. It has been accepted for inclusion in Columbia Chronicle by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. Sport~ECEIVED The Chocolate Turner Cup bound Messiah resurrects Nt.~· 2 :'! 2001 COLVMJJ!A ·,... Back Pc€')LLEGE LmRA}fy; Internet cheating creates mixed views But now students are finding By Christine Layous new ways to help ease their Staff Writer workload by buying papers o fT the Internet. "Plagiarism is a serious To make it easier for stu offense and is not, by any dents, there are Web sites that means, c<,mdoned or encour offer papers for a price. aged by Genius Papers." Geniuspapers.com was even A disclaimer with that mes featured on the search engine sage would be taken serious. Yahoo. They offer access to but how seriously when it term papers written by stu comes from an Internet site dents for a subscription of only that's selling term papers? $9.95 a year. -

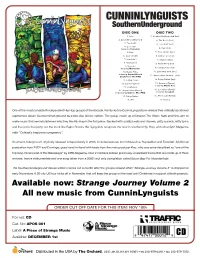

Strange Journey Volume 2 All New Music from Cunninlynguists

DISC ONE DISC TWO 1. Intro 1. SouthernUnderground (Inst) 2. SouthernUnderground 2. The South (Inst) 3. The South 3. Love Ain't (Inst) 4. Love Ain't 4. Rain (Inst) featuring Tonedeff 5. Rain 5. Doin’ Alright (Inst) 6. Doin’ Alright 6. Old School (Inst) 7. Interlude 1 7. Seasons (Inst) 8. Old School 8. Nasty Filthy (Inst) 9. Seasons 9. Falling Down (Inst) featuring Masta Ace 10. Nasty Filthy 10. Sunrise/Sunset (Inst) featuring Supastition & 11. Appreciation (Remix) - (Inst) Cashmere The PRO 11. Falling Down 12. Dying Nation (Inst) 12. Sunrise/Sunset 13. Seasons (Remix) featuring Masta Ace 13. Interlude 2 14. Appreciation (Remix) 14. Love Ain't (Remix) featuring featuring Cashmere The PRO Tonedeff 15. Dying Nation 15. The South (Remix) 16. War 16. Karma One of the most consistent independent Hip Hop groups of the decade, Kentucky trio CunninLynguists re-release their critically acclaimed sophomore album SouthernUnderground as a two disc deluxe edition. The group, made up of Deacon The Villain, Natti and Kno, aim to make music that reminds listeners why they like Hip Hop in the first place. Backed with quality beats and rhymes, gritty sounds, witty lyrics and low ends that jump out the trunk like Rajon Rondo, the ‘Lynguists recapture the soul in southern Hip Hop, with what Spin Magazine calls “Outkast’s tragicomic poignancy”. SouthernUnderground, originally released independently in 2003, includes features from Masta Ace, Supastition and Tonedeff. Additional production from RJD2 and Domingo, goes hand-in-hand with beats from the main producer Kno, who was once described as “one of the top loop-miners east of the Mississippi” by URB Magazine. -

Is Hip Hop Dead?

IS HIP HOP DEAD? IS HIP HOP DEAD? THE PAST,PRESENT, AND FUTURE OF AMERICA’S MOST WANTED MUSIC Mickey Hess Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hess, Mickey, 1975- Is hip hop dead? : the past, present, and future of America’s most wanted music / Mickey Hess. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-275-99461-7 (alk. paper) 1. Rap (Music)—History and criticism. I. Title. ML3531H47 2007 782.421649—dc22 2007020658 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright C 2007 by Mickey Hess All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2007020658 ISBN-13: 978-0-275-99461-7 ISBN-10: 0-275-99461-9 First published in 2007 Praeger Publishers, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.praeger.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vii INTRODUCTION 1 1THE RAP CAREER 13 2THE RAP LIFE 43 3THE RAP PERSONA 69 4SAMPLING AND STEALING 89 5WHITE RAPPERS 109 6HIP HOP,WHITENESS, AND PARODY 135 CONCLUSION 159 NOTES 167 BIBLIOGRAPHY 179 INDEX 187 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The support of a Rider University Summer Fellowship helped me com- plete this book. I want to thank my colleagues in the Rider University English Department for their support of my work. -

Read Book the Exile Waiting

THE EXILE WAITING PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Vonda N McIntyre | 324 pages | 22 Oct 2019 | Handheld Press | 9781912766093 | English | United Kingdom The Exile Waiting PDF Book McIntyre's world is intriguing and haunting--the caverns, view spoiler [the slow realization that the city of Center is also underground and that it's like this because we are on what can only be a post-nuclear-collapse Earth hide spoiler ] , the elusive Sphere, which we never see the way we expect even as its talked about contstantly view spoiler [and the novel ends with our protagonist headed off Earth and out into the Sphere, insiting that Earth be no longer forgotten hide spoiler ] , the various forms of mind-linkage. There are no discussion topics on this book yet. Quondame 3. McIntyre: Superluminal Nautilus. Sep 11, fromcouchtomoon rated it really liked it. This will work for background filler characters, but when some of your main characters are still close to mysteries when the story ends, the reader is left sadly unfulfilled. The primary characters are Mischa a young thief with telepathic abilities, trapped by her exceptionally dysfunctional family , Jan Hikaru more of an observer , and Subtwo part of a behavorial experienced, he has been twinned with an unrelated "pseudosib" Subone, who is presented as more a collection of stereotypical behaviors. From above descend two outworlders, apparently twins, but actually linked only by their telepathic bond. This was a crucial insight for Diaspora Judaism, those living in Babylon, Egypt, or elsewhere, deprived of their former institutions. Slavery is a big theme in this novel but even the top citizens of the world seem to be stuck in a less than stellar environment. -

God Loves Ugly

"This Minneapolis indie rap hero has potential to spare, delivering taut, complex rhyme narratives with everyman earnestness." -ROLLING STONE STREET DATE: 1.20.09 ATMOSPHERE GOD LOVES UGLY Repackaged, remastered and uglier than ever, the critically acclaimed third official studio release from Atmosphere, God Loves Ugly, is back after being out of print for over a year. The God Loves RSE-0031 Ugly re-issue also features a FREE bonus DVD. Format: CD+DVD / 2LP+DVD Packaging: Digi-Pak Originally released as the limited Sad Clown Bad Box Lot: 30 File Under: Rap/Hip Hop “A” Dub 4 (The Godlovesugly Release Parties) DVD, Parental Advisory: Yes it features 2 hours of live performance footage, Street Date: 1.20.09 backstage shenanigans, several special guest appearances and music videos for “Godlovesugly”, CD-826257003126 LP-826257003119 “Summersong” and “Say Shh”. Out of print +26257-AADBCg +26257-AADBBj for years, this DVD has been repackaged in a custom sleeve that comes inserted in with the re-issue of God Loves Ugly. TRACKLISTING: 1. ONEMOSPHERE 2. THE BASS AND THE MOVEMENT SELLING POINTS: 3. GIVE ME •Produced by Ant (Atmosphere, Brother Ali, Felt, etc.) 4. F*@CK YOU LUCY God Loves Ugly has scanned over 174,000 RTD. 5. HAIR • 6. GODLOVESUGLY •Catalog sales history of over a million units. 7. A SONG ABOUT A FRIEND •Current release When Life Gives You Lemons, You Paint 8. FLESH That Shit Gold scanned 36,526 in it’s first week and 9. SAVES THE DAY 10. LOVELIFE debuted #5 on the Billboard Top 200. 11. BREATHING 12. -

ALEX DELGADO Production Designer

ALEX DELGADO Production Designer PROJECTS DIRECTORS STUDIOS/PRODUCERS THE KEYS OF CHRISTMAS David Meyers YouTube Red Feature OPENING NIGHTS Isaac Rentz Dark Factory Entertainment Feature Los Angeles Film Festival G.U.Y. Lady Gaga Rocket In My Pocket / Riveting Short Film Entertainment MR. HAPPY Colin Tilley Vice Short Film COMMERCIALS & MUSIC VIDEOS SOL Republic Headphones, Kraken Rum, Fox Sports, Wendy’s, Corona, Xbox, Optimum, Comcast, Delta Airlines, Samsung, Hasbro, SONOS, Reebok, Veria Living, Dropbox, Walmart, Adidas, Go Daddy, Microsoft, Sony, Boomchickapop Popcorn, Macy’s Taco Bell, TGI Friday’s, Puma, ESPN, JCPenney, Infiniti, Nicki Minaj’s Pink Friday Perfume, ARI by Ariana Grande; Nicki Minaj - “The Boys ft. Cassie”, Lil’ Wayne - “Love Me ft. Drake & Future”, BOB “Out of My Mind ft. Nicki Minaj”, Fergie - “M.I.L.F.$”, Mike Posner - “I Took A Pill in Ibiza”, DJ Snake ft. Bipolar Sunshine - “Middle”, Mark Ronson - “Uptown Funk”, Kelly Clarkson - “People Like Us”, Flo Rida - “Sweet Spot ft. Jennifer Lopez”, Chris Brown - “Fine China”, Kelly Rowland - “Kisses Down Low”, Mika - “Popular”, 3OH!3 - “Back to Life”, Margaret - “Thank You Very Much”, The Lonely Island - “YOLO ft. Adam Levine & Kendrick Lamar”, David Guetta “Just One Last Time”, Nicki Minaj - “I Am Your Leader”, David Guetta - “I Can Only Imagine ft. Chris Brown & Lil’ Wayne”, Flying Lotus - “Tiny Tortures”, Nicki Minaj - “Freedom”, Labrinth - “Last Time”, Chris Brown - “She Ain’t You”, Chris Brown - “Next To You ft. Justin Bieber”, French Montana - “Shot Caller ft. Diddy and Rick Ross”, Aura Dione - “Friends ft. Rock Mafia”, Common - “Blue Sky”, Game - “Red Nation ft. Lil’ Wayne”, Tyga “Faded ft. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

Brother Ali Hip-Hop Artist / Activist Brother Ali Is a Highly Respected Hip Hop Artist, Speaker and Activist from Minneapolis, MN

Brother Ali Hip-Hop Artist / Activist Brother Ali is a highly respected Hip Hop artist, speaker and activist from Minneapolis, MN. His decade long resume includes six critically acclaimed albums, mentorships with Iconic Hip Hop legends Chuck D and Rakim and Previous Speaking Engagements: performances on late night talk shows with Conan O Brien and Jimmy Fallon. He’s been the subject of Al-Jazeera and NPR pieces and was a keynote speaker at this year’s Nobel Peace Prize Forum. He’s landed coveted press features such Keynote presenter - Nobel Peace as Rolling Stone’s 40th anniversary “Artist to Watch” and Source Magazine’s “Hip Prize forum, Topic: Hip Hop, Islam and Hop Quotables”. Global Politics Ali has won the hearts and minds of Hip Hop fans world wide with his intimate song writing, captivating live performances and outspoken stance on issues Featured performer/presenter - of Justice and Human Dignity. In 2007, Ali was flagged by The US Department Chicago University with Dr. Cornel of Homeland Security for his controversial critique of America’s human rights West, Amy Goodman of Democracy violations in his song/video “Uncle Sam Goddamn”. In the summer of 2012, Ali was Now and Tavis Smiley, Topic: Poverty arrested in an act of civil disobedience as an organizer of Minnesota’s Occupy in America. Homes movement to defend Twin Cities homeowners from unjust foreclosures. Brother Ali’s latest album, Mourning in America and Dreaming in Color is his Solo lecturer - Stanford University, manifesto on the political, socioeconomic and cultural suffering in modern hosted by Jeff Chang, Topic: Activism, American life, as well as a declaration of hope and possibility for a brighter future. -

Exposing Corruption in Progressive Rock: a Semiotic Analysis of Gentle Giant’S the Power and the Glory

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2019 EXPOSING CORRUPTION IN PROGRESSIVE ROCK: A SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF GENTLE GIANT’S THE POWER AND THE GLORY Robert Jacob Sivy University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2019.459 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Sivy, Robert Jacob, "EXPOSING CORRUPTION IN PROGRESSIVE ROCK: A SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF GENTLE GIANT’S THE POWER AND THE GLORY" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 149. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/149 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Bumbershoot Aesop Rock Niki&The Dove 11.09.12

11.09.12 page page page 6 bumbershoot 8 Aesop rock 10 niki&the dove cover art by lindsay stribling 2 in cue 11.09.12 college radio is the specialization and niche programming that it meet our about delivers to a broad audience. This blew my mind because it was so staff Top 5 Albums ever in cue profoundly accurate. YES! This is Welcome to In Cue, why radio matters. your campus radio College radio o#ers the cur- 1) Neutral Milk Hotel “Aeroplane over the Sea” station’s written con- rency that we all crave as well as nection to the masses. the education that accompanies 2) Wilco “Yankee Hotel Foxtrot” - a person telling you, “Hey, I chose 3) Elliot Smith “A basement on a Hill” views, articles, and these songs for you, I vouch for 4) T Rex “Electric Warrior” updates on what KUOI them. They are good.” If you be- FM has been up to this lieve, as I always have, that KUOI 5) Radiohead “The Bends” hosts some of the coolest kids on Nae Hakala year. We are here to STATION MANGER answer the question: campus, then you can have faith in what they are sharing with “Why does radio you. Sure, I initially tuned in for indie-rock and punk, but I stayed 1) Death Cab for Cutie “Transatlanticism” even matter, for garage and psych. Who knew 2) Death From Above 1979 “You’re a Women I’m a Machine” anymore?” these genres were still thriving? A 3) Animal Collective “Strawberry Jam” KUOI DJ knew, and he shared it with me. -

Sonic Jihadâ•Flmuslim Hip Hop in the Age of Mass Incarceration

FIU Law Review Volume 11 Number 1 Article 15 Fall 2015 Sonic Jihad—Muslim Hip Hop in the Age of Mass Incarceration SpearIt Follow this and additional works at: https://ecollections.law.fiu.edu/lawreview Part of the Other Law Commons Online ISSN: 2643-7759 Recommended Citation SpearIt, Sonic Jihad—Muslim Hip Hop in the Age of Mass Incarceration, 11 FIU L. Rev. 201 (2015). DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.25148/lawrev.11.1.15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by eCollections. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Law Review by an authorized editor of eCollections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 37792-fiu_11-1 Sheet No. 104 Side A 04/28/2016 10:11:02 12 - SPEARIT_FINAL_4.25.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 4/25/16 9:00 PM Sonic Jihad—Muslim Hip Hop in the Age of Mass Incarceration SpearIt* I. PROLOGUE Sidelines of chairs neatly divide the center field and a large stage stands erect. At its center, there is a stately podium flanked by disciplined men wearing the militaristic suits of the Fruit of Islam, a visible security squad. This is Ford Field, usually known for housing the Detroit Lions football team, but on this occasion it plays host to a different gathering and sentiment. The seats are mostly full, both on the floor and in the stands, but if you look closely, you’ll find that this audience isn’t the standard sporting fare: the men are in smart suits, the women dress equally so, in long white dresses, gloves, and headscarves. -

Pop Music with a Purpose: the Organization Of

Pop Music with a Purpose: The Organization of Contemporary Religious Music in the United States by Adrienne Michelle Krone Department of Religion Duke University Date: __________________________ Approved: _______________________________ David Morgan, Supervisor _______________________________ Yaakov Ariel _______________________________ miriam cooke Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Religion in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 Copyright by Adrienne Michelle Krone 2011 ABSTRACT Pop Music with a Purpose: The Organization of Contemporary Religious Music in the United States by Adrienne Michelle Krone Department of Religion Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ David Morgan, Supervisor ___________________________ Yaakov Ariel ___________________________ miriam cooke An abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Religion in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 Abstract Contemporary Religious Music is a growing subsection of the music industry in the United States. Talented artists representing a vast array of religious groups in America express their religion through popular music styles. Christian Rock, Jewish Reggae and Muslim Hip-Hop are not anomalies; rather they are indicative of a larger subculture of radio-ready religious music. This pop music has a purpose but it is not a singular purpose. This music might enhance the worship experience, provide a wholesome alternative to the unsavory choices provided by secular artists, infiltrate the mainstream culture with a positive message, raise the level of musicianship in the religious subculture or appeal to a religious audience despite origins in the secular world.