Assessing the Post–July 15 Turkish Military

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Offensive Against the Syrian City of Manbij May Be the Beginning of a Campaign to Liberate the Area Near the Syrian-Turkish Border from ISIS

June 23, 2016 Offensive against the Syrian City of Manbij May Be the Beginning of a Campaign to Liberate the Area near the Syrian-Turkish Border from ISIS Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) fighters at the western entrance to the city of Manbij (Fars, June 18, 2016). Overview 1. On May 31, 2016, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a Kurdish-dominated military alliance supported by the United States, initiated a campaign to liberate the northern Syrian city of Manbij from ISIS. Manbij lies west of the Euphrates, about 35 kilometers (about 22 miles) south of the Syrian-Turkish border. In the three weeks since the offensive began, the SDF forces, which number several thousand, captured the rural regions around Manbij, encircled the city and invaded it. According to reports, on June 19, 2016, an SDF force entered Manbij and occupied one of the key squares at the western entrance to the city. 2. The declared objective of the ground offensive is to occupy Manbij. However, the objective of the entire campaign may be to liberate the cities of Manbij, Jarabulus, Al-Bab and Al-Rai, which lie to the west of the Euphrates and are ISIS strongholds near the Turkish border. For ISIS, the loss of the area is liable to be a severe blow to its logistic links between the outside world and the centers of its control in eastern Syria (Al-Raqqah), Iraq (Mosul). Moreover, the loss of the region will further 112-16 112-16 2 2 weaken ISIS's standing in northern Syria and strengthen the military-political position and image of the Kurdish forces leading the anti-ISIS ground offensive. -

An Increasingly Undependable Ally Turkey

Turkey: An Increasingly Undependable Ally April 2015 Task Force Co-Chairs Ambassador Morton Abramowitz Former U.S. Ambassador to Turkey Ambassador Eric Edelman Former U.S. Ambassador to Turkey Task Force Members Henri Barkey Aaron Lobel Bernard L. and Bertha F. Cohen Professor of Internal Relations, Founder and President, America Abroad Lehigh University Media Svante Cornell Alan Makovsky Research Director, Central Asia-Caucasus Institute and Silk Road Former Senior Professional Staff Member, Studies Program House Foreign Affairs Committee Ambassador Paula Dobriansky Admiral (ret.) Gregory Johnson Former Under Secretary of State for Global Affairs Former Commander of U.S. Naval Forces, Europe; Senior Advisor, Bipartisan Policy John Hannah Center Former Assistant for National Security Affairs to the Vice President General (ret.) Charles Wald Halil Karaveli Former Deputy Commander, U.S. European Senior Fellow, Central Asia-Caucasus Institute and Silk Road Command; Bipartisan Policy Center Board Studies Program Member David Kramer Senior Director for Human Rights and Human Freedoms, McCain Institute for International Leadership 2 Foreign Policy Project Staff Blaise Misztal Project Director Jessica Michek Project Assistant ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report would not have been possible without the substantive contributions of Gareth Jenkins and Svante Cornell. We also gratefully acknowledge the assistance of BPC interns Seyma Akyol, William Spach, and Chloe Barz for their contributions. DISCLAIMER This report is a product of BPC’s National Security Program. The findings expressed herein are those solely of the National Security Program, though no member may be satisfied with every formulation in the report. The report does not necessarily represent the views or opinions of BPC, its founders, or its board of directors. -

Policy Notes for the Trump Notes Administration the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2018 ■ Pn55

TRANSITION 2017 POLICYPOLICY NOTES FOR THE TRUMP NOTES ADMINISTRATION THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2018 ■ PN55 TUNISIAN FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ AND SYRIA AARON Y. ZELIN Tunisia should really open its embassy in Raqqa, not Damascus. That’s where its people are. —ABU KHALED, AN ISLAMIC STATE SPY1 THE PAST FEW YEARS have seen rising interest in foreign fighting as a general phenomenon and in fighters joining jihadist groups in particular. Tunisians figure disproportionately among the foreign jihadist cohort, yet their ubiquity is somewhat confounding. Why Tunisians? This study aims to bring clarity to this question by examining Tunisia’s foreign fighter networks mobilized to Syria and Iraq since 2011, when insurgencies shook those two countries amid the broader Arab Spring uprisings. ©2018 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ NO. 30 ■ JANUARY 2017 AARON Y. ZELIN Along with seeking to determine what motivated Evolution of Tunisian Participation these individuals, it endeavors to reconcile estimated in the Iraq Jihad numbers of Tunisians who actually traveled, who were killed in theater, and who returned home. The find- Although the involvement of Tunisians in foreign jihad ings are based on a wide range of sources in multiple campaigns predates the 2003 Iraq war, that conflict languages as well as data sets created by the author inspired a new generation of recruits whose effects since 2011. Another way of framing the discussion will lasted into the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. center on Tunisians who participated in the jihad fol- These individuals fought in groups such as Abu Musab lowing the 2003 U.S. -

45 the RESURRECTION of SYRIAN KURDISH POLITICS by Ro

THE RESURRECTION OF SYRIAN KURDISH POLITICS By Rodi Hevian* This article examines the current political landscape of the Kurdish region in Syria, the role the Kurds have played in the ongoing Syrian civil war, and intra-Kurdish relations. For many years, the Kurds in Syria were Iraqi Kurdistan to Afrin in the northwest on subjected to discrimination at the hands of the the Turkish border. This article examines the Ba’th regime and were stripped of their basic current political landscape of the Kurdish rights.1 During the 1960s and 1970s, some region in Syria, the role the Kurds have played Syrian Kurds were deprived of citizenship, in the ongoing conflict, and intra-Kurdish leaving them with no legal status in the relations. country.2 Although Syria was a key player in the modern Kurdish struggle against Turkey and Iraq, its policies toward the Kurds there THE KURDS IN SYRIA were in many cases worse than those in the neighboring countries. On the one hand, the It is estimated that there are some 3 million Asad regime provided safe haven for the Kurds in Syria, constituting 13 percent of Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and the Syria’s 23 million inhabitants. They mostly Kurdish movements in Iraq fighting Saddam’s occupy the northern part of the country, a regime. On the other hand, it cracked down on region that borders with Iraqi Kurdistan to the its own Kurds in the northern part of the east and Turkey to the north and west. There country. Kurdish parties, Kurdish language, are also some major districts in Aleppo and Kurdish culture and Kurdish names were Damascus that are populated by the Kurds. -

Syrian Arab Republic

Syrian Arab Republic News Focus: Syria https://news.un.org/en/focus/syria Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Syria (OSES) https://specialenvoysyria.unmissions.org/ Syrian Civil Society Voices: A Critical Part of the Political Process (In: Politically Speaking, 29 June 2021): https://bit.ly/3dYGqko Syria: a 10-year crisis in 10 figures (OCHA, 12 March 2021): https://www.unocha.org/story/syria-10-year-crisis-10-figures Secretary-General announces appointments to Independent Senior Advisory Panel on Syria Humanitarian Deconfliction System (SG/SM/20548, 21 January 2021): https://www.un.org/press/en/2021/sgsm20548.doc.htm Secretary-General establishes board to investigate events in North-West Syria since signing of Russian Federation-Turkey Memorandum on Idlib (SG/SM/19685, 1 August 2019): https://www.un.org/press/en/2019/sgsm19685.doc.htm Supporting the future of Syria and the region - Brussels V Conference, 29-30 March 2021 https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-ministerial-meetings/2021/03/29-30/ Supporting the future of Syria and the region - Brussels IV Conference, 30 June 2020: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-ministerial-meetings/2020/06/30/ Third Brussels conference “Supporting the future of Syria and the region”, 12-14 March 2019: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-ministerial-meetings/2019/03/12-14/ Second Brussels Conference "Supporting the future of Syria and the region", 24-25 April 2018: http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-ministerial-meetings/2018/04/24-25/ -

Shifting Policies in Conflict Arenas: a Cosine Similarity and Text Mining Analysis of Turkey’S Syria Policy, 2012-2016

Journal of Strategic Security Volume 11 Number 4 Article 1 Shifting Policies in Conflict Arenas: A Cosine Similarity and Text Mining Analysis of Turkey’s Syria Policy, 2012-2016 Brendon J. Cannon Khalifa University of Science and Technology, [email protected] Mikiyasu Nakayama University of Tokyo, [email protected] Daisuke Sasaki Tohoku University, [email protected] Ash Rossiter Khalifa University of Science and Technology, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss pp. 1-19 Recommended Citation Cannon, Brendon J.; Nakayama, Mikiyasu; Sasaki, Daisuke; and Rossiter, Ash. "Shifting Policies in Conflict Arenas: A Cosine Similarity and extT Mining Analysis of Turkey’s Syria Policy, 2012-2016." Journal of Strategic Security 11, no. 4 (2019) : 1-19. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.11.4.1690 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss/vol11/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Strategic Security by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Shifting Policies in Conflict Arenas: A Cosine Similarity and Text Mining Analysis of Turkey’s Syria Policy, 2012-2016 Abstract Turkish policy towards the Syrian civil war, as operationalized in relation to the implementation of no-fly zones, safe zones or buffer zones, has been the subject of much debate among scholars. As the number of foreign states acting in Syria has steadily increased since the onset of the crisis, Turkish policies have similarly shifted. -

The Fall of Dabiq and the Fall of the Caliphate

0 The fall of Dabiq and the fall of the Caliphate Shaul Shay October 2016 Dabiq, which lies about 10km from the border with Turkey, features in Islamic apocalyptic prophecies as the site of an end-of-times showdown between Muslims and their "Roman" enemies based on a hadith. The Prophet Muhammad is believed to have said that "the last hour will not come" until Muslims vanquished the Romans at "Dabiq or al-Amaq" - both in the Syria-Turkey border region - on their way to conquer Constantinople (Istanbul).1 But in October 2016, the fall of Dabiq did not start the apocalypse but the countdown to the end of the Islamic state. Operation "Euphrates Shield" - The attack on Dabiq ISIS fighters fancied themselves as the true Muslims, and the Turkish-backed rebel forces as the infidels. But fears that the thousand-or-so jihadi fighters holed up in Dabiq would fight to the death were quelled, as the militants simply took to their heels and ran, leaving the Free Syrian Army to walk in without much of a battle.2 In the operation's early weeks, Jarabulus and Al-Rai became the first two major settlements to be captured from the ISIS. The attack on Dabiq started on October 15, 2016. Rebels have also taken the villages of Irshaf and Ghaitun, which would cut off Dabiq and another large village, Soran – all in preparation for a ground offensive on the two areas. ISIS had been sending reinforcements into Dabiq over the past weeks, including one of their most elite units, known as Jaish al-Isra, which arrived in recent days3. -

A Blood-Soaked Olive: What Is the Situation in Afrin Today? by Anthony Avice Du Buisson - 06/10/2018 01:23

www.theregion.org A blood-soaked olive: what is the situation in Afrin today? by Anthony Avice Du Buisson - 06/10/2018 01:23 Afrin Canton in Syria’s northwest was once a haven for thousands of people fleeing the country’s civil war. Consisting of beautiful fields of olive trees scattered across the region from Rajo to Jindires, locals harvested the land and made a living on its rich soil. This changed when the region came under Turkish occupation this year. Operation Olive Branch: Under the governance of the Afrin Council – a part of the ‘Democratic Federation of Northern Syria’ (DFNS) – the region was relatively stable. The council’s members consisted of locally elected officials from a variety of backgrounds, such as Kurdish official Aldar Xelil who formerly co-headed the Movement for a Democratic Society (TEVDEM) – a political coalition of parties governing Northern Syria. Children studied in their mother tongue— Kurdish, Arabic, or Syriac— in a country where the Ba’athists once banned Kurdish education. The local Self-Defence Forces (HXP) worked in conjunction with the People’s Protection Units (YPG) to keep the area secure from existential threats such as Turkish Security forces (TSK) and Free Syrian Army (FSA) attacks. This arrangement continued until early 2018, when Turkey unleashed a full-scale military operation called ‘ Operation Olive Branch’ to oust TEVDEM from Afrin. The Turkish government views TEVDEM and its leading party, the Democratic Union Party (PYD), as an extension of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) – listed as a terrorist organisation in Turkey. Under the pretext of defending its borders from terrorism, the Turkish government sent thousands of troops into Afrin with the assistance of forces from its allies in Idlib and its occupied Euphrates Shield territories. -

S/2012/503 Consejo De Seguridad

Naciones Unidas S/2012/503 Consejo de Seguridad Distr. general 16 de octubre de 2012 Español Original: inglés Cartas idénticas de fecha 28 de junio de 2012 dirigidas al Secretario General y al Presidente del Consejo de Seguridad por el Representante Permanente de la República Árabe Siria ante las Naciones Unidas Siguiendo instrucciones de mi Gobierno y en relación con mis cartas de fechas 16 a 20 y 23 a 25 de abril, 7, 11, 14 a 16, 18, 21, 24, 29 y 31 de mayo y 1, 4, 6, 7, 11, 19, 20, 25 y 27 de junio de 2012, tengo el honor de trasmitir adjunta una lista pormenorizada de las violaciones del cese de la violencia cometidas por grupos armados en Siria el 24 de junio de 2012 (véase el anexo). Agradecería que la presente carta y su anexo se distribuyeran como documento del Consejo de Seguridad. (Firmado) Bashar Ja’afari Embajador Representante Permanente 12-55140 (S) 241012 241012 *1255140* S/2012/503 Anexo de las cartas idénticas de fecha 28 de junio de 2012 dirigidas al Secretario General y al Presidente del Consejo de Seguridad por el Representante Permanente de la República Árabe Siria ante las Naciones Unidas [Original: árabe] Sunday, 24 June 2012 Rif Dimashq governorate 1. On 23 June 2012 at 2020 hours, an armed terrorist group opened fire on a military barracks headquarters in Rif Dimashq. 2. On 23 June 2012 at 2100 hours, an armed terrorist group opened fire on law enforcement checkpoints in Shaffuniyah, Shumu' and Umara' in Duma, killing Private Muhammad al-Sa'dah and wounding three soldiers, including a first lieutenant. -

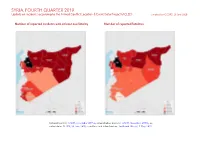

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; in- cident data: ACLED, 20 June 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 3058 397 1256 violence Development of conflict incidents from December 2017 to December 2019 2 Battles 1023 414 2211 Strategic developments 528 6 10 Methodology 3 Violence against civilians 327 210 305 Conflict incidents per province 4 Protests 169 1 9 Riots 8 1 1 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 5113 1029 3792 Disclaimer 8 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). Development of conflict incidents from December 2017 to December 2019 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). 2 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. The numbers included in this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data. -

The Kurdish Question in the Middle East

Strategic Sectors | Security & Politics The Kurdish Question in the Middle Panorama East: Regional Dynamics and Return to National Control Olivier Grojean its influence in Iran (via the PJAK), in Syria (via the Lecturer in Political Science PYD and its SDF, which now control numerous The European Centre for Sociology and Political Kurdish and Arab territories) and even in Iraq, near Science (CESSP), University of Paris I-Panthéon- Mont Qandil where it is based, but also in the Sorbonne and National Center for Scientific Research Maxmûr Kurdish refugee camp in Turkey and the (CNRS), Paris Yazidi regions of Sinjar. In sum, the past few dec- Strategic Sectors | Security & Politics ades have seen a rise in power of Kurdish political parties, which have managed to profoundly region- The past four decades have seen an increasing re- alize the Kurdish question by allying themselves with gionalization of the Kurdish question on the Middle regional or global powers. At once both the life- East scale. The Iranian Revolution and the Iran-Iraq blood and consequence of this regionalization, the War (1980-1988), the 1991 Gulf War and its con- rivalry between the conservative, liberal pole em- sequences throughout the 1990s, US intervention bodied by Barzani’s PDK and the post-Marxist revo- in Iraq in 2003, the Syrian revolution and its repres- lutionary pole embodied by the PKK has led to sion as of 2011 and finally, the increasing power of greater interconnection of Kurdish issues in differ- 265 the Islamic State as of 2014 have been important ent countries. vectors for the expansion of Kurdish issues. -

Two Routes to an Impasse: Understanding Turkey's

Two Routes to an Impasse: Understanding Turkey’s Kurdish Policy Ayşegül Aydin Cem Emrence turkey project policy paper Number 10 • December 2016 policy paper Number 10, December 2016 About CUSE The Center on the United States and Europe (CUSE) at Brookings fosters high-level U.S.-Europe- an dialogue on the changes in Europe and the global challenges that affect transatlantic relations. As an integral part of the Foreign Policy Studies Program, the Center offers independent research and recommendations for U.S. and European officials and policymakers, and it convenes seminars and public forums on policy-relevant issues. CUSE’s research program focuses on the transforma- tion of the European Union (EU); strategies for engaging the countries and regions beyond the frontiers of the EU including the Balkans, Caucasus, Russia, Turkey, and Ukraine; and broader European security issues such as the future of NATO and forging common strategies on energy security. The Center also houses specific programs on France, Germany, Italy, and Turkey. About the Turkey Project Given Turkey’s geopolitical, historical and cultural significance, and the high stakes posed by the foreign policy and domestic issues it faces, Brookings launched the Turkey Project in 2004 to foster informed public consideration, high‐level private debate, and policy recommendations focusing on developments in Turkey. In this context, Brookings has collaborated with the Turkish Industry and Business Association (TUSIAD) to institute a U.S.-Turkey Forum at Brookings. The Forum organizes events in the form of conferences, sem- inars and workshops to discuss topics of relevance to U.S.-Turkish and transatlantic relations.