Digital Content From: Irish Historic Towns Atlas (IHTA), No. 24, Sligo Authors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4¼N5 E0 4¼N5 4¼N4 4¼N4 4¼N4 4¼N5

#] Mullaghmore \# Bundoran 0 20 km Classiebawn Castle V# Creevykeel e# 0 10 miles ä# Lough #\ Goort Cairn Melvin Cliffony Inishmurray 0¸N15 FERMANAGH LEITRIM Grange #\ Cashelgarran ATLANTIC Benwee Dun Ballyconnell#\ Benbulben #\ R(525m) Head #\ Portacloy Briste Lough Glencar OCEAN Carney #\ Downpatrick 1 Raghly #\ #\ Drumcliff # Lackan 4¼N16 Manorhamilton Erris Head Bay Lenadoon Broad Belderrig Sligo #\ Rosses Point #\ Head #\ Point Aughris Haven ä# Ballycastle Easkey Airport Magheraghanrush \# #\ Rossport #\ Head Bay Céide #\ Dromore #– Sligo #\ ä# Court Tomb Blacklion #\ 0¸R314 #4 \# Fields West Strandhill Pollatomish e #\ Lough Gill Doonamo Lackan Killala Kilglass #\ Carrowmore ä# #æ Point Belmullet r Bay 4¼N59 Innisfree Island CAVAN #\ o Strand Megalithic m Cemetery n #\ #\ R \# e #\ Enniscrone Ballysadare \# Dowra Carrowmore i Ballintogher w v #\ Lough Killala e O \# r Ballygawley r Slieve Gamph Collooney e 4¼N59 E v a (Ox Mountains) Blacksod i ä# skey 4¼N4 Lough Mullet Bay Bangor Erris #\ R Rosserk Allen 4¼N59 Dahybaun Inishkea Peninsula Abbey SLIGO Ballinacarrow#\ #\ #\ Riverstown Lough Aghleam#\ #\ Drumfin Crossmolina \# y #\ #\ Ballina o Bunnyconnellan M Ballymote #\ Castlebaldwin Blacksod er \# Ballcroy iv Carrowkeel #\ Lough R #5 Ballyfarnon National 4¼N4 #\ Conn 4¼N26 #\ Megalithic Cemetery 4¼N59 Park Castlehill Lough Tubbercurry #\ RNephin Beg Caves of Keash #8 Arrow Dugort #÷ Lahardane #\ (628m) #\ Ballinafad #\ #\ R Ballycroy Bricklieve Lough Mt Nephin 4¼N17 Gurteen #\ Mountains #\ Achill Key Leitrim #\ #3 Nephin Beg (806m) -

Irish Schools Athletics Champions 1916-2015 Updated June 15 2015

Irish Schools Athletics Champions 1916-2015 Updated June 15 2015 In February 1916 Irish Amateur Athletic Association (IAAA) circularised the principal schools in Ireland regarding the advisability of holding Schoolboys’ Championships. At the IAAA’s Annual General Meeting held on Monday 3rd April, 1916 in Wynne’s Hotel, Dublin, the Hon. Secretary, H.M. Finlay, referred to the falling off in the number of affiliated clubs due to the number of athletes serving in World War I and the need for efforts to keep the sport alive. Based on responses received from schools, the suggestion to hold Irish Schoolboys’ Championships in May was favourably considered by the AGM and the Race Committee of the IAAA was empowered to implement this project. Within a week a provisional programme for the inaugural athletics meeting to be held at Lansdowne Road on Saturday 20th May, 1916 had been published in newspapers, with 7 events and a relay for Senior and 4 events and a relay for Junior Boys. However, the championships were postponed "due to the rebellion" and were rescheduled to Saturday 23rd September, 1916, at Lansdowne Road. In order not to disappoint pupils who were eligible for the championships on the original date of the meeting, the Race Committee of the IAAA decided that “a bona fide schoolboy is one who has attended at least two classes daily at a recognised primary or secondary school for three months previous to 20 th May, except in case of sickness, and who was not attending any office or business”. The inaugural championships took place in ‘quite fine’ weather. -

The Irish Contribution to Americas Independence

THE IRISH CONTRIBUTION TO A M E R I C A ’ S I N D E P E N D E N C E The Irish Co nt rib ut io n t o ’ Am e rica s Inde pe nde nce By THOMA S HOB B S MAGINNISS, JR . P UB LISHED B Y DOIRE PUBLISHING COMPANY P H IL A D E LP H I A 19 13 1 1 THE IRE B LISHING Co . Copyright, 9 3, by DO PU , Philadelphia, PRESS OF WM F . FEL . L CO . PREFACE It becomes nations as well as individuals not to think of them s lves mor h Sel e i hl than th ou ht but to think sob rl . e g y ey g , e y f exaggerat ion de tracts from their characte r without adding to their power; but a greater and more dangerous fault is an habitual de eciation of their real resources and a consequent ” want o se geh ance — DKI f lj . GO N . NE of the faults chargeable against the Irish people , and particularly Americans of Irish de f scent , is that they are ignorant o the achieve m of I i 18 ents their race n the past . ITh s probably due to the fact that the people of Ireland have for generations been taught to believe that everything respectable has come from England and that the English are a superior race . m Indeed , an attempt has been made to i pres s the same on f theory the minds o Americans , and perhaps the most - pernicious falsehood promulgated by pro English writers , who exert a subtle influence in spreading the gospel of “ ” - Anglo Saxon superiority, is that America owes her liberty, her benevolent government , and even her pros “ ” “ — pe rity t o her English forefathers and Anglo Saxon n bloo d . -

Lower Carboniferous Rocks Between the Curlew and Ox Mountains, Northwestern Ireland

Lower Carboniferous rocks between the Curlew and Ox Mountains, Northwestern Ireland OWEN ARNOLD DIXON CONTENTS i Introduction 7 I 2 Stratal succession 73 (A) General sequence 73 (B) Moy-Boyle Sandstones 73 (c) Dargan Limestone 74 (D) Oakport Limestone 75 (F.) Lisgorman Shale Group 76 (F) Bricklieve Limestone 78 (o) Roscunnish Shale 84 (H) Namurian rocks 84 3 Zonal stratigraphy . 85 (a) Fauna . 85 (B) Zonal correlation 88 4 History of sedimentation 9o 5 Regional correlation. 95 6 References 98 SUMMARY Rocks in the Ballymote area, occupying one of sedimentary environments of a shallow shelf several broad downwarps of inherited cale- sea. The main episodes (some repeated) include donoid trend, provide a crucial link between the deposition of locally-derived conglomerates Vis6an successions north of the Highland and sandstones in a partly enclosed basin; the Boundary line (represented locally by the Ox accumulation of various thick, clear-water Mountains) and successions to the south, part limestones, partly in continuation with ad- of the extensive 'shelf' limestone of central jacent basins; and the influx of muddy detrital Ireland. The sequence, exceeding xo7o metres sediments from a more distant source. (35oo it) in thickness, ranges in age from early The rocks contain a succession of rich and to latest Vis~an (C~S1 to/2) and is succeeded, diverse benthonic faunas, predominantly of generally without interruption, by thick upper corals and brachiopods, but near the top these Carboniferous shales. The succession of differ- give way to several distinctive goniatite- ent rock types reflects changing controls in the lamellibranch faunas. i. Introduction THE LOWER CARBONIFEROUS rocks of the Ballymote map area underlie a shallow physiographic trough extending east-northeast from Swinford, Co. -

Aarch Matters

AARCH MATTERS COVID-19 UPDATE: The effects of the novel coronavirus have affected us all, especially impacting the ability of nonprofits and cultural organizations like AARCH to deliver its usual slate of rich slate of programming and events. It is at this time we must remain resilient. Although this year’s events may be postponed and/or cancelled, we are remaining optimistic that we will bring this content to YOU in some way going forward. Please READ ON, and carry our message of resilience, hope, and love, even if we may not be able to share in our adventures together in person this year. Be safe, and remember that the sun will continue to rise each day. A PATCHWORK of RESILIENCE CHRONICLING SUSTAINABILITY, ENERGY, WORK, AND STORIES EMBODIED IN OUR REGION Resilience – “the capacity to recover quickly from difficulties” – is a trait escaping enslavement, early 20th century Chinese freedom seekers jailed that allows plants, animals, and humans to adapt and even thrive in as they came south from Canada, and the thousands of immigrants now adversity. And it is a characteristic that we admire and learn from, as it’s flooding across a tiny, illegal crossing to find security and hope in Canada. what makes or should make each generation better than the last. In this Or there is the story of how Inez Milholland and other North Country era of looming climate change and now with the scourge of the women fought for their right to vote and be heard, and the extraordinary coronavirus sweeping across the globe, we’ve realized that we need to story of Isaac Johnson, a formerly enslaved African American stone create a world that is safer, sustainable, more equitable, and resilient and mason who settled in the St. -

Sligo: COUNTY GEOLOGY of IRELAND 1

Sligo: COUNTY GEOLOGY OF IRELAND 1 SLIGOSLIGOSLIGO AREA OF COUNTY: 1,836 square kilometres or 708 square miles COUNTY TOWN: Sligo OTHER TOWNS: Strandhill, Tobercurry, Ballymote GEOLOGY HIGHLIGHTS: Ben Bulben and Truskmore Plateau, caves and karst, vanishing lake, Carboniferous sea-floor fossils, Ice Age landforms. AGE OF ROCKS: Precambrian; Devonian to Carboniferous, Paleogene Streedagh Point and Ben Bulben Lower Carboniferous limestones with the isolated mountain of Ben Bulben in the distance. This was carved by ice sheets as they moved past during the last Ice Age. 2 COUNTY GEOLOGY OF IRELAND: Sligo Geological Map of County Sligo Pale Purple: Precambrian Dalradian rocks; Pale yellow: Precambrian Quartzite; Green: Silurian sediments; Red: Granite; Beige:Beige:Beige: Devonian sandstones; Blue gray:Blue gray: Lower Carboniferous sandstones; Light blue: Lower Carboniferous limestone; Brown:Brown:Brown: Upper Carboniferous shales. Geological history The oldest rocks in the county form a strip of low hills extending along the south side of Lough Gill westwards past Collooney towards the Ox Mountains, with a small patch on Rosses Point north-west of Sligo town. They are schists and gneisses, metamorphosed from 1550 million year old [Ma] sedimentary rocks by the heat and pressure of two episodes of mountain building around 605 Ma and 460 Ma. Somewhat younger rocks, around 600 Ma, form the main massif of the Ox Mountains in the west of the county. They include schists and quartzites, once sedimentary rocks that have been less severely metamorphosed than the older rocks further east. In the far south of the county, around Lough Gara and the Curlew Mountains, are found a great thickness of conglomerates (pebble beds) and sandstones, with some layers rich in volcanic ash and fragments of lava. -

Irish Landscape Names

Irish Landscape Names Preface to 2010 edition Stradbally on its own denotes a parish and village); there is usually no equivalent word in the Irish form, such as sliabh or cnoc; and the Ordnance The following document is extracted from the database used to prepare the list Survey forms have not gained currency locally or amongst hill-walkers. The of peaks included on the „Summits‟ section and other sections at second group of exceptions concerns hills for which there was substantial www.mountainviews.ie The document comprises the name data and key evidence from alternative authoritative sources for a name other than the one geographical data for each peak listed on the website as of May 2010, with shown on OS maps, e.g. Croaghonagh / Cruach Eoghanach in Co. Donegal, some minor changes and omissions. The geographical data on the website is marked on the Discovery map as Barnesmore, or Slievetrue in Co. Antrim, more comprehensive. marked on the Discoverer map as Carn Hill. In some of these cases, the evidence for overriding the map forms comes from other Ordnance Survey The data was collated over a number of years by a team of volunteer sources, such as the Ordnance Survey Memoirs. It should be emphasised that contributors to the website. The list in use started with the 2000ft list of Rev. these exceptions represent only a very small percentage of the names listed Vandeleur (1950s), the 600m list based on this by Joss Lynam (1970s) and the and that the forms used by the Placenames Branch and/or OSI/OSNI are 400 and 500m lists of Michael Dewey and Myrddyn Phillips. -

Definitive Guide to the Top 500 Schools in Ireland

DEFINITIVE GUIDE TO THE TOP 500 SCHOOLS IN IRELAND These are the top 500 secondary schools ranked by the average proportion of pupils gaining places in autumn 2017, 2018 and 2019 at one of the 10 universities on the island of Ireland, main teacher training colleges, Royal College of Surgeons or National College of Art and Design. Where schools are tied, the proportion of students gaining places at all non-private, third-level colleges is taken into account. See how this % at university Boys Girls Student/ staff ratio Telephone % at third-level Area Type % at university Boys Girls Student/ staff ratio Telephone Rank Previous rank % at third-level Type % at university Boys Girls Student/ staff ratio Telephone Area Type Rank Previous rank Area % at third-level guide was compiled, back page. Schools offering only senior cycle, such as the Institute of Education, Dublin, and any new schools are Rank Previous rank excluded. Compiled by William Burton and Colm Murphy. Edited by Ian Coxon 129 112 Meanscoil Iognaid Ris, Naas, Co Kildare L B 59.9 88.2 1,019 - 14.1 045-866402 269 317 Rockbrook Park School, Rathfarnham, Dublin 16 SD B 47.3 73.5 169 - 13.4 01-4933204 409 475 Gairmscoil Mhuire, Athenry, Co Galway C M 37.1 54.4 266 229 10.0 091-844159 Fee-paying schools are in bold. Gaelcholaisti are in italics. (G)=Irish-medium Gaeltacht schools. *English-speaking schools with Gaelcholaisti 130 214 St Finian’s College, Mullingar, Co Westmeath L M 59.8 82.0 390 385 13.9 044-48672 270 359 St Joseph’s Secondary School, Rush, Co Dublin ND M 47.3 63.3 416 297 12.3 01-8437534 410 432 St Mogue’s College, Belturbet, Co Cavan U M 37.0 59.0 123 104 10.6 049-9523112 streams or units. -

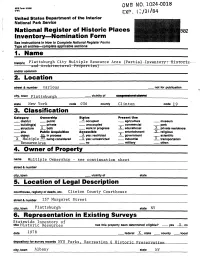

1. Name Historic Plattsburgh City Multiple Resource Area —————And Arciii Tec Tural ' Pfopert Ies) — And/Or Common '

NO. 1024-0018 NFS Form 10-900 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register off Historic Plaices Inventory Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type ail entries complete applicable sections 1. Name historic Plattsburgh City Multiple Resource Area —————and Arciii tec tural ' Pfopert ies) — and/or common ' street & number various not for publication city,town Plattsburgh vicinity of state New York code 036 county Clinton code 19 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public ^ occupied agriculture museum buikMng(s) private unoccupied commercial park structure X both work In progress X educational X private residence Site Public Acquisition Accessible . entertainment X religious object NA in process X yes: restricted X government __ scientific X Multiple m being considered _ X. yes: unrestricted industrial X transportation Resource Area no military other: 4. Owner off Property name Multiple Ownership - see continuation sheet street & number city, town __ vicinity of state courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Clinton County Courthouse street & number 137 Margaret Street city, town Plattsburgh state NY 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Statewide Inventory of title Historic Resources has this property been determined eligible? . yes X no date 1978 federal X state __ county local depository for survey records NYS Parks, Recreation § Historic Preservation city, town Albany state NY 7. Description Condition 9f1/Pck one .Check one NAexcellent deteriorated ^^ unaltered NA original site «. good ruins altered moved cl?»e fatt unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance The Historic Resources of the City of Plattsburgh were identified by means of a comprehensive survey/inventory of structures conducted between June and November, 1978. -

N4 Sligo Inner Relief Road and County Extension

N4 Sligo Inner Relief Road And County Extension Contract 1 – Final Report Report on the Archaeological Excavation of Neolithic, Iron Age and Post Medieval Pits SLIGO at CORPORATION Area 1C, Caltragh, Sligo Licence Number: 03E0544 Licensee: Sue McCabe ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONSULTANCY February 2005 SERVICES PROJECT DETAILS Project Archaeological Excavation Archaeologist Sue McCabe Client Sligo Borough and County Council, Town Hall, Co Sligo Road Scheme N4 Sligo Inner Relief Road and County Extension Site Area 1C Townland Caltragh Parish St John’s Nat Grid Ref 168790, 333800 RMP No N/A Licence No 03E0544 Planning Ref N/A Project Date 28th July 2003 Report Date February 2005 Archaeological Consultancy Services Ltd N4 SIRR, Caltragh 1C NON-TECHNICAL SUMMARY The N4 Sligo Inner Relief Road and County Extension (N4 SIRR) development involves the construction of a new dual carriageway extending north from the Carrowroe Roundabout on the existing N4 in Tonafortes Townland. This will run through a rural environment at first, then continue through the Sligo urban area and terminate at the Michael Hughes Bridge, at the junction of Custom House Quay and Ballast Quay in Rathedmond Townland. The development covers a distance of 4.2 km. An extensive programme of archaeological investigation associated with the development commenced in 2001 with test excavations being carried out by Mary Henry Ltd. These test excavations took the form primarily of a series of 2m-wide trenches excavated along the length of the route. They were aimed at assessing the archaeological potential of the route and a number of definite and potential archaeological features already identified there. -

IH Dublin Profiles

International House Dublin Incorporating High School Ireland Dear Agent/ Parent, I am delighted to introduce this new guide to the very best of our Irish High schools. Ireland has one of the highest participation rates in second and third level education in the OECD and its standard of educational excellence is recognised worldwide. Due to the fact that even private schools are heavily subsidised by the government, Ireland represents exceptionally good value in terms of cost and quality. We present here a selection of carefully chosen public and private schools, together with a short introduction to the Irish Education system. We have expanded our High School Department, in terms both of staffing and partner schools and I am confident that we can provide a superior service to agents and students at a price which you will find competitive. You will also have the comfort that you are working with International House, an organisation internationally recognised for it’s commitment to quality. I would like to thank our High School team at International House Dublin, under the leadership of Tom Smyth, for putting together a guide which is informative, well structured and easy to use. With every best wish from the staff at High School Ireland/ International House, ________________________ Laurence Finnegan, Director www.ihdublin.com Page | 1 International House Dublin Incorporating High School Ireland WHY STUDY IN IRELAND? Ireland is an English speaking country. Ireland has one of the best education systems in Europe. Irish people are renowned for their friendliness and hospitality which greatly contributes to the ease with which overseas students adapt to student life in Ireland. -

Special Education Allocations to Post Primary Schools 21/22

Special Education Allocations to Post Primary Schools 21/22 County Roll School Type School Special Special Class Mainstream Special Class Total SNAs Number Education Teaching SNA SNA 21/22 Teaching Posts Allocation Allocation Hours 21/22 21/22 21/22 Carlow 61120E Post Primary St. Mary's Academy C.B.S. 135.00 3.00 1.00 5.00 6.00 Carlow 61130H Post Primary St. Mary's Knockbeg College 115.50 3.00 1.00 4.00 5.00 Carlow 61140K Post Primary St. Leo's College 131.50 0.00 1.00 0.00 1.00 Carlow 61141M Post Primary Presentation College 158.00 0.00 1.00 0.00 1.00 Carlow 61150N Post Primary Presentation/De La Salle College 141.00 3.00 3.00 4.00 7.00 Carlow 70400L Post Primary Borris Vocational School 97.50 1.50 1.00 2.00 3.00 Carlow 70410O Post Primary Coláiste Eóin 55.40 0.00 0.50 0.00 0.50 Carlow 70420R Post Primary Tyndall College 203.60 6.00 3.00 6.50 9.50 Carlow 70430U Post Primary Coláiste Aindriú 46.50 1.50 1.00 2.00 3.00 Carlow 70440A Post Primary Gaelcholaiste Cheatharlach 32.50 0.00 1.00 0.00 1.00 Carlow 91356F Post Primary Tullow Community School 154.50 3.00 1.00 4.00 5.00 Cavan 61051L Post Primary St. Clare's College 129.50 1.50 2.50 1.00 3.50 Cavan 61060M Post Primary St Patricks College 143.51 0.00 1.00 0.00 1.00 Cavan 61070P Post Primary Loreto College 61.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Cavan 61080S Post Primary Royal School Cavan 69.65 0.00 3.00 0.00 3.00 Cavan 70350W Post Primary St.