Mapping the White British Response to Ethnic Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bristol: a City Divided? Ethnic Minority Disadvantage in Education and Employment

Intelligence for a multi-ethnic Britain January 2017 Bristol: a city divided? Ethnic Minority disadvantage in Education and Employment Summary This Briefing draws on data from the 2001 and 2011 Figure 1. Population 2001 and 2011. Censuses and workshop discussions of academic researchers, community representatives and service providers, to identify 2011 patterns and drivers of ethnic inequalities in Bristol, and potential solutions. The main findings are: 2001 • Ethnic minorities in Bristol experience greater disadvantage than in England and Wales as a whole in 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% education and employment and this is particularly so for White British Indian Black African Black African people. White Irish Pakistani Black Caribbean Gypsy or Irish Traveller Bangladeshi Other Black • There was a decrease in the proportion of young people White other Chinese Arab with no educational qualifications in Bristol, for all ethnic Mixed Other Asian Any other groups, between 2001 and 2011. • Black African young people are persistently disadvantaged Source: Census 2001 & 2011 in education compared to their White peers. • Addressing educational inequalities requires attention Ethnic minorities in Bristol experience greater disadvantage to: the unrepresentativeness of the curriculum, lack of than the national average in education and employment, diversity in teaching staff and school leadership and poor as shown in Tables 1 and 2. In Education, ethnic minorities engagement with parents. in England and Wales on average have higher proportions • Bristol was ranked 55th for employment inequality with qualifications than White British people but this is between White British and ethnic minorities. not the case in Bristol, and inequality for the Black African • People from Black African (19%), Other (15%) and Black Caribbean (12.7%) groups had persistently high levels of Measuring Local Ethnic Inequalities unemployment. -

New Forecasts for the Uk's Ethnic Groups

THE FUTURE IS DIVERSITY: NEW FORECASTS FOR THE UK’S ETHNIC GROUPS Philip Rees1, Pia Wohland2, Stephen Clark1, Nik Lomax1, and Paul Norman1 1School of Geography, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK 2 Hull York Medical School, University of Hull, Hull, HU6 7RX, UK Contact: [email protected] Paper for the European Population Conference, 31 August to 3 September, 2016, Mainz, Germany Abstract Developed countries with below replacement fertility face population ageing. This is slowed by a net inflow of international migrants. The influx leads to a population of increasing ethnic diversity. Most researchers focus on a historical understanding of the ethnic transition process. We use this understanding to forecast the population of the United Kingdom, projecting the ethnic transition forward for 50 years. This chapter describes the context, model, estimates and assumptions for projections of ethnic group populations in England at local authority scale, and in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Demographic component rates for ethnic populations are estimated using 2001 and 2011 Census data and vital statistics. A bi-regional cohort-component model is used with assumptions are aligned to recent official projections. We pay special attention to international migration assumptions because of the prospects of a new relationship between the UK and the rest of the European Union, consequent on UK electors voting in the referendum of 23 June 2016 to leave the European Union. Official assumptions and project assumptions about UK international migration are compared for their direct effect on the UK population between 2011 and 2061. There are also indirect effects through the higher natural increase for younger groups, which we illustrate for one set of assumptions. -

Who Identifies As Welsh? National

November 2014 DYNAMICS OF DIVERSITY: EVIDENCE FROM THE 2011 CENSUS ESRC Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE) Who identifies asWelsh? National identities and ethnicity in Wales Summary • In Wales, 1.8 million people identify only as Welsh (58% of • People born in Wales are more likely to report only a Welsh the population) and 218,000 identify as Welsh and British national identity (76%). People born in Oceania and North (7% of the population). America and the Caribbean are more likely to report only a Welsh national identity (14% and 10% respectively) than • Mixed ethnic groups are more likely to identify with only people born in England (8%). a Welsh national identity than all other ethnic minority groups, with the highest proportion being amongst the White and Black Caribbean (59%) group. Introduction Since devolution, the Welsh Government has sought to • Mixed groups are more likely to identify only as Welsh support a common Welsh national identity through the ‘One (47%) than mixed groups in England (46%) and Scotland Wales’ strategy. This has included, for example, strengthening (37%) identify as English or Scottish only. the place of ‘Wales in the World’ and continued support for 1 • The ethnic groups in Wales most likely to identify only as the Welsh language. The inclusion of a question on national British are Bangladeshi (64%), Pakistani (56%) and Black identity in the 2011 Census provides us with an opportunity Caribbean (41%). to examine how people living in Wales describe themselves. The Census shows that 58% of people living in Wales identify • Welsh only national identity is reported more for younger only as Welsh and a further 7% identify as Welsh and British.2 people aged 0 to 17 than those aged 18 or older. -

Sunday March 21, 2021 Loathing the Working Class, Censoring Conservatives, Future of Real Estate, Employment, Outsourcing

What Happens Next – Sunday March 21, 2021 Loathing the Working Class, Censoring Conservatives, Future of Real Estate, Employment, Outsourcing My name is Larry Bernstein. What Happens Next offers listeners an in-depth analysis of the most pressing issues of the day. Our experts are given just SIX minutes to present. This is followed by a Q&A period for deeper engagement. I think you will find this discussion to be both informative and provocative. This program is moderated to be politically neutral. Our speakers will give their opinions and then we encourage you to make up your own mind. This week’s topics include Loathing the Working Class, Censoring Conservatives, the Future of Real Estate, How the new stimulus will impact employment, and Outsourcing Work Our first presenter today is Paul Embery who is a trade union activist and columnist for Unherd. He is the author of a new book entitled Despised: Why the Modern Left Loathes the Working Class. Paul lives in the UK and writes about the Labor parties disregard for the working-class voter. We will discuss the implications of UK elites shock at Brexit voters and their belief that these citizens are deplorables. Our second speaker is Eric Kaufmann who is a Professor of Politics at the University of London’s Birkbeck College. We met Eric on What Happens Next during our discussion of political polling when he discussed the failure of pollsters to properly account for Trump voters. Today, Eric will discuss his recent article in the Wall Street Journal about the current wave of censorship of conservative academics on college campuses. -

Whiteshift: Populism, Immigration and the Future

REVIEWS 91 and the American National Election Studies Kaufmann, Eric: (ANES) datasets. He shows that it is in fact values, rather than income levels, that can ex- WHITESHIFT: POPULISM, plain most of the two votes. The crux of his IMMIGRATION AND THE FUTURE explanation is in psychological attitudes – he OF WHITE MAJORITIES. argues that people of conservative and so- called authoritarian predisposition (both of London: Allen Lane. 2018. 624 pages. which are partly heritable) are those that were most likely to vote for Trump or Brexit. Con- DOI: 10.5817/PC2020‑1 ‑91 servatives because they oppose change, and authoritarians because they prefer order and What happened? This question has been on uniformity to dissent and diversity (p. 199). many minds, not just Hillary Clinton’s, in the Immigration will be perceived more negative- wake of the 2016 election of Donald Trump ly by people of these dispositions because it and the UK referendum to exit the European brings both change and diversity. Union. Mainstream media analyses have often Looking at the data, Kaufmann shows, offered economic explanations in the form for example, that when controlling for age of the ‘left-behind’ argument, pointing to the and education, attitude to immigration can disparities between wealthy regions benefit- explain a large part of support for Trump, ing from globalization, and economically de- whereas income levels barely register. More pressed areas that have not benefited as much. interestingly, the ANES data show that over Eric Kaufmann, a professor of politics at Birk- two-thirds of those who support capital pun- beck, University of London, has in his latest ishment voted for Trump, whereas only 20 % book Whiteshift provided a comprehensive of those who oppose it did (pp. -

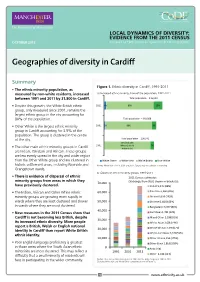

Geographies of Diversity in Cardiff

LOCAL DYNAMICS OF DIVERSITY: EVIDENCE FROM THE 2011 CENSUS OCTOBER 2013 Prepared by ESRC Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE) Geographies of diversity in Cardiff Summary Figure 1. Ethnic diversity in Cardiff, 1991-2011 • The ethnic minority population, as measured by non-white residents, increased a) Increased ethnic minority share of the population, 1991-2011 between 1991 and 2011 by 31,800 in Cardiff. Total population – 346,090 • Despite this growth, the White British ethnic 2011 4% 80% 15% group, only measured since 2001, remains the largest ethnic group in the city accounting for 80% of the population. Total population – 310,088 • Other White is the largest ethnic minority 2001 2% 88% 9% group in Cardiff accounting for 3.5% of the population. The group is clustered in the centre of the city. Total population – 296,941 93% (includes 1991 White Other & 7% • The other main ethnic minority groups in Cardiff White Irish) are Indian, Pakistani and African. These groups are less evenly spread in the city and wider region than the Other White group and are clustered in White Other White Irish White British Non-White historic settlement areas, including Riverside and Notes: White Irish <1% in 2001 and 2011. Figures may not add due to rounding. Grangetown wards. b) Growth of ethnic minority groups, 1991-2011 • There is evidence of dispersal of ethnic 2011 Census estimates minority groups from areas in which they 70,000 (% change from 2001 shown in brackets): have previously clustered. Indian 9,435 (88%) • The Indian, African and Other White ethnic 60,000 Pakistani 6,960 (40%) minority groups are growing more rapidly in African 6,639 (162%) wards where they are least clustered and slower 50,000 Chinese 6,182 (105%) in wards where they are most clustered. -

Read the Report

Will HUTTON Sir Malcolm RIFKIND Con COUGHLIN Peter TATCHELL Does West know best? bright blue AUTUMN 2011 flickr.com/familymwr Contributors Matt Cavanagh is the Associate Director for UK Migration Policy at the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) Con Coughlin is the Executive Foreign Editor of The Daily Telegraph Sir Malcolm Rifkind MP Brendan Cox is the Director of Policy and Advocacy at Save the Children Stephen Crabb MP is MP for Preseli Pembrokeshire and Leader of Project Umubano, the Conservatives’ social action project in Rwanda and Sierra Leone Richard Dowden is Director of the Royal African Society and author of Africa: Altered States, Ordinary Miracles Maurice Fraser is a Senior Fellow in European Politics at the London School of Economics (LSE) and an Associate Fellow at Chatham House Peter Tatchell Will Hutton is a columnist for The Observer , executive vice-chair of The Work Foundation and Principal of Hertford College, Oxford University Professor Eric Kaufmann is Professor of Politics at Birkbeck College, University of London, the author of Shall the Religious Inherit the Earth and was a Visiting Fellow at the Kennedy School, Harvard in 2008-9. Sir Malcolm Rifkind MP is MP for Kensington and was Foreign Secretary, 1995-7 Victoria Roberts is Deputy Chairman of the Tory Reform Group Will Hutton Henneke Sharif is an Associate at Counterpoint and a Board Member of Bright Blue Guy Stagg is the Online Lifestyle Editor for The Daily Telegraph Peter Tatchell is a human rights campaigner Garvan Walshe is the Publications Director -

Curriculum Vitae Simon

Simon Hix FBA FRSA Department of Social and Political Sciences European University Institute Via dei Roccettini 9 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI), Italy Principal Current Positions Stein Rokkan Chair in Comparative Politics (from September 2021) Associate Editor, European Union Politics Founder and Chairman, VoteWatch.eu AISBL (pro bono) Fellow of the British Academy Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts Education PhD in Political and Social Science, European University Institute, Florence, 1995 MSc(Econ) in West European Politics, LSE, 1992 BSc(Econ) in Government and History, LSE, 1990 Publications Books B9 Simon Hix and Bjørn Høyland (2021) The Political System of the European Union, 4th edn, London: Palgrave, forthcoming. B8 Simon Hix and Bjørn Høyland (2011) The Political System of the European Union, 3rd edn, London: Palgrave. Translated into Spanish, Albanian, and Romanian. B7 Simon Hix (2008) What’s Wrong with the European Union and How to Fix It, London: Polity. B6 Simon Hix, Abdul Noury and Gérard Roland (2007) Democratic Politics in the European Parliament, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Translated into Romanian. Won the APSA Fenno Prize for best book on legislative studies in 2007. Honourable mention, EUSA, best book in 2007-08. B5 Simon Hix (2005) The Political System of the European Union, 2nd edn, London: Palgrave. Translated into Bulgarian, Greek, Lithuanian, Polish, Serbian, and Ukrainian. B4 Simon Hix and Roger Scully (eds) (2003) The European Parliament at Fifty. Special issue of Journal of Common Market Studies 41(2). B3 Klaus Goetz and Simon Hix (eds) (2001) Europeanised Politics? European Integration and National Political Systems, London: Frank Cass. -

A LOST TRIBE: BRITAIN’S YOUNG EUROSCEPTICS” Author: Dr Rakib Ehsan

ADEFENDING LOST TRIBE: EUROPE: “GLOBAL BRITAIN” ANDBRITAIN’S THE FUTURE YOUNG OFEUROSCEPTICS EUROPEAN GEOPOLITICSBY DR RAKIB EHSAN BY JAMES ROGERS DEMOCRACY | FREEDOM | HUMAN RIGHTS ReportAugust No. 2018/ 20191 Published in 2019 by The Henry Jackson Society The Henry Jackson Society Millbank Tower 21-24 Millbank London SW1P 4QP Registered charity no. 1140489 Tel: +44 (0)20 7340 4520 www.henryjacksonsociety.org © The Henry Jackson Society, 2019. All rights reserved. Title: “A LOST TRIBE: BRITAIN’S YOUNG EUROSCEPTICS” Author: Dr Rakib Ehsan Cover image: https://www.shutterstock.com/image-photo/london-uk- january-15-2019-brexit-1285916578?src=t7YMbzew2z7o58KThFXZeg-1-32 Ink Drop / Shutterstock.com ADEFENDING LOST TRIBE: EUROPE: “GLOBAL BRITAIN” ANDBRITAIN’S THE FUTURE YOUNG OFEUROSCEPTICS EUROPEAN GEOPOLITICSBY DR RAKIB EHSAN BY JAMES ROGERS DEMOCRACY | FREEDOM | HUMAN RIGHTS ReportAugust No. 2018/ 20191 A LOST TRIBE: BRITAIN’S YOUNG EUROSCEPTICS About the Author Dr Rakib Ehsan is a Research Fellow at the Henry Jackson Society. Rakib specialises in the socio-political behaviour and attitudes of British ethnic minorities, with a particular focus on the UK’s Bangladeshi and Pakistani ethnic groups. He holds a BA Politics & International Relations (First-Class Honours), MSc Democracy, Politics & Governance (Pass with Distinction), and a PhD in Political Science, all from Royal Holloway, University of London. His PhD investigated the effects of social integration for British ethnic minorities. Rakib has had research published by a number of UK-based think-tanks, including Runnymede Trust, Policy Exchange and Intergenerational Foundation, as well as the Mackenzie Institute, an independent security think-tank based in Toronto, Canada. Acknowledgments I would like to express my thanks to all those who made my first HJS report possible. -

Final Copy 2019 05 07 Awad

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Awad, Will Title: ‘I’m a professional businessman not a professional Pakistani’ Media Representation of South Asian Businessmen in Thatcherite Britain, 1979-1990. General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. ‘I’m a professional businessman not a professional Pakistani’: Media Representation of South Asian Businessmen in Thatcherite Britain, 1979-1990. William Alexander Awad A dissertation submitted to the University of Bristol in accordance with the requirements for award of the degree of Master of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts, December 2018. -

North West Leicestershire District Council

Coalville (Ward) Demographics – Population Age structure Ethnic group Marital status Country of birth Religion Housing – Average House Price Number of Houses Housing tenure Housing Type Council tax band Page 1 of 14 Crime – Burglary, Assault Criminal damage, Theft (vehicle) Fires attended Other – Occupation groups Economically active / inactive General Health Qualifications and students Indices of deprivation Sources - Page 2 of 14 Demographics – Population Total population (2001) North West Great Coalville Leicestershire Britain All People 4494 85503 57103923 Males 2182 42240 27758419 Females 2312 43263 29345504 % of District population 5.2% Coalville Ward makes up 5.2% of the population for North West Leicestershire. Age structure Coalville No of People People aged 0 - 4 284 People aged 5 - 7 171 People aged 8 - 9 118 People aged 10 - 14 291 People aged 15 57 People aged 16 - 17 109 People aged 18 - 19 103 People aged 20 - 24 242 People aged 25 - 29 349 People aged 30 - 44 1036 People aged 45 - 59 743 People aged 60 - 64 201 People aged 65 - 74 374 People aged 75 - 84 267 People aged 85 - 89 93 People aged 90 & over 58 The table above shows the break down of the population in Coalville by age groups. Page 3 of 14 Age structure – The graph below looks at the age structure as a % and compares Coalville with that of North West Leicestershire. 25 23.04 23.02 21.21 20 Coalville Nortn West Leicestershire 16.53 15 10 8.39 8.32 7.76 6.47 6.42 6.32 5.99 5.89 5.94 5.84 5.38 5.06 4.77 5 4.47 3.8 3.6 2.62 2.59 2.42 2.29 2.29 2.07 1.95 1.27 1.29 1.24 1.22 0.51 0 0 - 4 5 - 7 8 - 9 10 - 14 15 16 - 17 18 - 19 20 - 24 25 - 29 30 - 44 45 - 59 60 - 64 65 - 74 75 - 84 85 - 89 90 & over The graph shows which age groups are most predominant. -

White Flight: the Emerging Story

When connected to the BHPS, the survey is • information can be linked to ward-level one of the few in the western world making it census data possible to track both the demographic • unlike national surveys, this allows for the backgrounds and attitudes of large numbers of analysis of how attitudes change at local Contact with individuals over time. level, how moving is connected to attitudes, immigrants and and how the local affects the national. minorities is not Rich data on mixed marriages, mixed-race individuals, friendships and households will Policy implications – what White flight: as important enable researchers to explore whether these the research says as some believe factors are associated with less white British Contact with immigrants and minorities in changing people leaving an area, lower levels of anti- is not as important as some believe in the emerging story attitudes. immigration sentiment and right-wing voting. changing attitudes because diverse areas are Pioneering research – a case study Diverse areas also transient, and transience affects white Other features of Understanding Society that attitudes more than diversity. are transient make the research possible include: – this affects • the large sample size permits analysis of Greater opposition in local authority areas white attitudes people living in ethnically diverse wards compared with smaller wards can be more than (segregated or integrated) and relatively explained by the idea that people with few white wards adjoining diverse ones face-to-face contacts with immigrants and diversity. • Wave 1 of the survey captured information minorities can be threatened by an awareness from 200 BNP and 200 UKIP supporters, of ethnic change in their wider area, but this Institute for Social and Economic sufficient to test a range of interesting sense of threat is reduced by contact with Research (ISER) variables minorities and immigrants who live close by.