Exotic Birds in the ABA Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January 2020.Indd

BROWN PELICAN Photo by Rob Swindell at Melbourne, Florida JANUARY 2020 Editors: Jim Jablonski, Marty Ackermann, Tammy Martin, Cathy Priebe Webmistress: Arlene Lengyel January 2020 Program Tuesday, January 7, 2020, 7 p.m. Carlisle Reservation Visitor Center Gulls 101 Chuck Slusarczyk, Jr. "I'm happy to be presenting my program Gulls 101 to the good people of Black River Audubon. Gulls are notoriously difficult to identify, but I hope to at least get you looking at them a little closer. Even though I know a bit about them, I'm far from an expert in the field and there is always more to learn. The challenge is to know the particular field marks that are most important, and familiarization with the many plumage cycles helps a lot too. No one will come out of this presentation an expert, but I hope that I can at least give you an idea what to look for. At the very least, I hope you enjoy the photos. Looking forward to seeing everyone there!” Chuck Slusarczyk is an avid member of the Ohio birding community, and his efforts to assist and educate novice birders via social media are well known, yet he is the first to admit that one never stops learning. He has presented a number of programs to Black River Audubon, always drawing a large, appreciative gathering. 2019 Wellington Area Christmas Bird Count The Wellington-area CBC will take place Saturday, December 28, 2019. Meet at the McDonald’s on Rt. 58 at 8:00 a.m. The leader is Paul Sherwood. -

TAG Operational Structure

PARROT TAXON ADVISORY GROUP (TAG) Regional Collection Plan 5th Edition 2020-2025 Sustainability of Parrot Populations in AZA Facilities ...................................................................... 1 Mission/Objectives/Strategies......................................................................................................... 2 TAG Operational Structure .............................................................................................................. 3 Steering Committee .................................................................................................................... 3 TAG Advisors ............................................................................................................................... 4 SSP Coordinators ......................................................................................................................... 5 Hot Topics: TAG Recommendations ................................................................................................ 8 Parrots as Ambassador Animals .................................................................................................. 9 Interactive Aviaries Housing Psittaciformes .............................................................................. 10 Private Aviculture ...................................................................................................................... 13 Communication ........................................................................................................................ -

Management of Racing Pigeons

37_Racing Pigeons.qxd 8/24/2005 9:46 AM Page 849 CHAPTER 37 Management of Racing Pigeons JAN HOOIMEIJER, DVM Open flock management, which is used in racing pigeon medicine, assumes the individual pigeon is less impor- tant than the flock as a whole, even if that individual is monetarily very valuable. The goal when dealing with rac- ing pigeons is to create an overall healthy flock com- posed of viable individuals. This maximizes performance and profit. Under ideal circumstances, problems are pre- vented and infectious diseases are controlled. In contrast, poultry and (parrot) aviculture medicine is based on the principles of the closed flock concept. With this concept, prevention of disease relies on testing, vaccinating and a strict quarantine protocol — measures that are not inte- gral to racing pigeon management. This difference is due to the very nature of the sport of pigeon racing; contact among different pigeon lofts (pigeon houses) constantly occurs. Every week during the racing season, pigeons travel — confined with thou- sands of other pigeons in special trucks — to the release site. Pigeons from different lofts are put together in bas- kets. Confused pigeons frequently enter a strange loft. In addition, training birds may come into contact with wild birds during daily flight sessions. Thus, there is no way to prevent exposure to contagious diseases within the pop- ulation or to maintain a closed flock. The pigeon fancier also must be aware that once a disease is symptomatic, the contagious peak has often already occurred, so pre- ventive treatment is too late. Treatment at this point may be limited to minimizing morbidity and mortality. -

Parrot Brochure

COMMON MEDICAL PROPER HOUSING COMPANION DISEASES PARROTS: 1.) Nutritional deficiencies - A variety of ocular, nasal, respiratory, reproductive LARGE & SMALL and skin disorders caused by chronically improper diets. 2.) Feather picking - A behavioral disorder, sometimes secondary to a primary medical problem, where the bird self-mutilates by picking out its own Maecenas feathers. It is most often due to depression from lack of mental Proper housing for a macaw and other large birds stimulation or companionship and more Finding the right parrot cage for your feathered commonly seen in larger species. friend depends on the size and needs of your Purchasing your pet birds only in pairs bird. For example, while a parakeet needs a can help prevent this disorder smaller cage that can sit on a counter-top or from developing." table; the macaw needs a HUGE cage practically 3.) Bumblefoot - All caged birds are the size of a small room! It is always safest to “go susceptible to developing “bumblefoot" big.” Avoid galvanized metal wiring due to the or pododermatitis. This disease manifests potential for lead poisoning, and clean the itself as blisters and infections of the feet substrate on the bottom of the cage daily to caused by dirty perches or perches that weekly. Birds are messy creatures that love to are all the same size, shape and made of dive into their food bowls! Perches should vary the same material. i.e. smooth wood. in size, shape and material; including various How best to care for these diverse woods, sand paper and cloth. Clean perches and colorful birds and to ensure regularly to prevent diseases of the feet. -

Nest Density and Success of Columbids in Puerto Rico ’

The Condor98:1OC-113 0 The CooperOrnithological Society 1996 NEST DENSITY AND SUCCESS OF COLUMBIDS IN PUERTO RICO ’ FRANK F. RIVERA-MILAN~ Department ofNatural Resources,Scientific Research Area, TerrestrialEcology Section, Stop 3 Puerta. de Tierra, 00906, Puerto Rico Abstract. A total of 868 active nests of eight speciesof pigeonsand doves (columbids) were found in 210 0.1 ha strip-transectssampled in the three major life zones of Puerto Rico from February 1987 to June 1992. The columbids had a peak in nest density in May and June, with a decline during the July to October flocking period, and an increasefrom November to April. Predation accountedfor 8 1% of the nest lossesobserved from 1989 to 1992. Nest cover was the most important microhabitat variable accountingfor nest failure or successaccording to univariate and multivariate comparisons. The daily survival rate estimates of nests constructed on epiphytes were significantly higher than those of nests constructedon the bare branchesof trees. Rainfall of the first six months of the year during the study accounted for 67% and 71% of the variability associatedwith the nest density estimatesof the columbids during the reproductivepeak in the xerophytic forest of Gulnica and dry coastal forest of Cabo Rojo, but only 9% of the variability of the nest density estimatesof the columbids in the moist montane second-growthforest patchesof Cidra. In 1988, the abundance of fruits of key tree species(nine speciescombined) was positively correlatedwith the seasonalchanges in nest density of the columbids in the strip-transects of Cayey and Cidra. Pairwise density correlationsamong the columbids suggestedparallel responsesof nestingpopulations to similar or covarying resourcesin the life zones of Puerto Rico. -

Commercial Members

Commercial Members ABC Pets, Humble, TX, www.abcbirds.com Graham, Jan, El Paso, TX, [email protected] Adventures In Birds & Pets Inc, Houston,TX, [email protected] Great Companions Bird Supplies, Warren, MN, American Racing Pigeon Union, Oklahoma City, OK www.greatcompanions.com Angelwood Nursery, Woodburn, OR, [email protected] Hawkins, Connie, Larwill, IN, [email protected] Animal Adventure Inc, Greendale, WI, www.animaladventurepets.com Hidden Forest Art Gallery, Fallbrook, CA, www.gaminiratnavira.com Animal Genetics Inc./Avian Biotech, Tallahassee, FL, Hill Country Aviaries, LLC, Dripping Springs, TX, [email protected] www.hillcountryaviaries.com Avey Incubator, Llc, Evergreen, CO, [email protected] Hobo’s Parrot-Dise, Clarence, NY, [email protected] Avian Adventures Aviary, Novato, CA, Hopper, Verleen, Spring, TX, [email protected] www.avianadventuresaviary.com Innovative Inclosures, Fallbrook, CA Avian Resources, San Dimas, CA Intl Fed Of Homing Pigeon Fanciers, Hicksville, NY, www.ifpigeon.com Avianelites, New Holland, IL, [email protected] Jewelry & Gifts, Antioch, CA, [email protected] Aviary Of Naples & Zoological Park, Naples, FL, [email protected] Jo’s Exotic Birds, Ltd., Kenosha, WI, www.jos-exoticbirds.com Bailey, Laura Santa Ana, CA, [email protected] Johnson, Cynthia, Mehama, OR, [email protected] Beach, Steve, Camp Verde, AZ, [email protected] Jungle Talk And Eight In One, Moorpark, CA, Bell’s Exotics, Inc, Wrightsville, GA, www.bellsexotics.com [email protected] Berkshire Aviary, -

Behavioural Adaptation of a Bird from Transient Wetland Specialist to an Urban Resident

Behavioural Adaptation of a Bird from Transient Wetland Specialist to an Urban Resident John Martin1,2*, Kris French1, Richard Major2 1 Institute for Conservation Biology and Environmental Management, School of Biological Sciences, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, New South Wales, Australia, 2 Terrestrial Ecology, Australian Museum, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia Abstract Dramatic population increases of the native white ibis in urban areas have resulted in their classification as a nuisance species. In response to community and industry complaints, land managers have attempted to deter the growing population by destroying ibis nests and eggs over the last twenty years. However, our understanding of ibis ecology is poor and a question of particular importance for management is whether ibis show sufficient site fidelity to justify site-level management of nuisance populations. Ibis in non-urban areas have been observed to be highly transient and capable of moving hundreds of kilometres. In urban areas the population has been observed to vary seasonally, but at some sites ibis are always observed and are thought to be behaving as residents. To measure the level of site fidelity, we colour banded 93 adult ibis at an urban park and conducted 3-day surveys each fortnight over one year, then each quarter over four years. From the quarterly data, the first year resighting rate was 89% for females (n = 59) and 76% for males (n = 34); this decreased to 41% of females and 21% of males in the fourth year. Ibis are known to be highly mobile, and 70% of females and 77% of males were observed at additional sites within the surrounding region (up to 50 km distant). -

Namibia & the Okavango

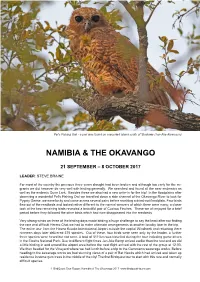

Pel’s Fishing Owl - a pair was found on a wooded island south of Shakawe (Jan-Ake Alvarsson) NAMIBIA & THE OKAVANGO 21 SEPTEMBER – 8 OCTOBER 2017 LEADER: STEVE BRAINE For most of the country the previous three years drought had been broken and although too early for the mi- grants we did however do very well with birding generally. We searched and found all the near endemics as well as the endemic Dune Lark. Besides these we also had a new write-in for the trip! In the floodplains after observing a wonderful Pel’s Fishing Owl we travelled down a side channel of the Okavango River to look for Pygmy Geese, we were lucky and came across several pairs before reaching a dried-out floodplain. Four birds flew out of the reedbeds and looked rather different to the normal weavers of which there were many, a closer look at the two remaining birds revealed a beautiful pair of Cuckoo Finches. These we all enjoyed for a brief period before they followed the other birds which had now disappeared into the reedbeds. Very strong winds on three of the birding days made birding a huge challenge to say the least after not finding the rare and difficult Herero Chat we had to make alternate arrangements at another locality later in the trip. The entire tour from the Hosea Kutako International Airport outside the capital Windhoek and returning there nineteen days later delivered 375 species. Out of these, four birds were seen only by the leader, a further three species were heard but not seen. -

Parrots in the London Area a London Bird Atlas Supplement

Parrots in the London Area A London Bird Atlas Supplement Richard Arnold, Ian Woodward, Neil Smith 2 3 Abstract species have been recorded (EASIN http://alien.jrc. Senegal Parrot and Blue-fronted Amazon remain between 2006 and 2015 (LBR). There are several ec.europa.eu/SpeciesMapper ). The populations of more or less readily available to buy from breeders, potential factors which may combine to explain the Parrots are widely introduced outside their native these birds are very often associated with towns while the smaller species can easily be bought in a lack of correlation. These may include (i) varying range, with non-native populations of several and cities (Lever, 2005; Butler, 2005). In Britain, pet shop. inclination or ability (identification skills) to report species occurring in Europe, including the UK. As there is just one parrot species, the Ring-necked (or Although deliberate release and further import of particular species by both communities; (ii) varying well as the well-established population of Ring- Rose-ringed) parakeet Psittacula krameri, which wild birds are both illegal, the captive populations lengths of time that different species survive after necked Parakeet (Psittacula krameri), five or six is listed by the British Ornithologists’ Union (BOU) remain a potential source for feral populations. escaping/being released; (iii) the ease of re-capture; other species have bred in Britain and one of these, as a self-sustaining introduced species (Category Escapes or releases of several species are clearly a (iv) the low likelihood that deliberate releases will the Monk Parakeet, (Myiopsitta monachus) can form C). The other five or six¹ species which have bred regular event. -

The African Sacred Ibis (Threskiornis Aethiopicus)

Oasi di Bolgheri The African sacred ibis (Threskiornis aethiopicus) A new species for the Bolgheri Bird Sanctuary Historically the distribution of the species has affected the sub Saharan and the North African desert belt, as well as southern Spain and the Middle East. Sighted for the first time in Italy in 1989 in the Regional Park of the Lame Sesia in Piedmont, the species has gradually expanded to the Po valley. The first report of the presence of the species in Bolgheri consisting of 4 individuals was recorded by the WWF guide of the Bolgheri Bird Sanctuary Paola Visicchio during a guided tour on the 8th of November 2014. I confirmed the reporting on the 10th of November 2014 by photographing 12 individuals, including some young, recognizable by the black sooty coloring of the neck and head unlike adults, who are not distinguishable by sex and have a shiny black head and beak. The species was again observed on 14.11.2014 in the marshy pastures of Le Cioccaie (9 individuals) and on the 15th of November during the opening of the Bolgheri Bird Sanctuary visits (4 individuals). The African sacred ibis graze in gregarious form in search of food consisting mainly of invertebrates and small vertebrates, just like the cattle egrets. The curved beak allows them to probe the muddy ground of the bird sanctuary to identify potential prey. The myth of the sacred ibis In the representations of Egyptian hieroglyphics, the deity Thoth is mostly depicted with the mask of a sacred ibis, the large bird of the Nile. -

The Nanday Conure

The Nanday Conure wM it NY Ti at at It It it It 1K tt Conures have been known to Those birds are in contrast with The bird has red thighs brownish attack and eat smaller bird species their behavior in the wild not suit pink feet reddishbrown eyes and during migration in the fall Thus it able for keeping in community blackishgray bill The birds length follows that should will fellow 12 its logically they not type aviary they peck at is 12 to 30 to 32 cm be placed with smaller birds in the species and any other species that wings are to 18 to 19 same housing comes too close to them and their cm and its tail 17 loud almost constant screeching can Providing that the birds Aratinga he very disturbing to other birds accommodations are roomy they Many ornithologists consider especially those breeding will breed quite quickly The nesting the Nanday Conure member of the This screeching also makes boxes should not be placed too genus Aratinga these birds indeed them poor candidates for keeping high because the birds like to sit on come in many different plumages indoors though we have seen sever top of them and watch the world go their the is the and even size and origin are al hand reared Aratingas sitting on by When female sitting on not common denominators They all their perches and talking great deal eggs the male may sit for hours on come from the New World from They can indeed he tamed quite top of the nest box The female lays both the male Mexico south to most parts of South quickly and will then be very affec two to four eggs and America -

Mitred Conure Control on Maui

UC Agriculture & Natural Resources Proceedings of the Vertebrate Pest Conference Title Mitred Conure Control on Maui Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7jc2c0g2 Journal Proceedings of the Vertebrate Pest Conference, 26(26) ISSN 0507-6773 Authors Radford, Adam Penniman, Teya Publication Date 2014 DOI 10.5070/V426110411 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Mitred Conure Control on Maui Adam Radford and Teya Penniman Maui Invasive Species Committee, Makawao, Hawai‘i ABSTRACT: Hawai‘i has no native parrots (Psittacidae), but at least two species of this family have naturalized on the island of Maui, the result of accidental or deliberate releases of pet birds. A breeding pair of mitred conures was illegally released in approximately 1986 on the north shore of Maui. At its peak, a population of over 150 birds was documented, demonstrating that conures in Hawai‘i can be highly productive in the wild. These non-native birds pose a threat to Hawaiian ecosystems, agricultural productivity, and quality of life. They are highly adaptable, reproduce rapidly, eat a variety of fruits and seeds, are extremely loud, can carry viral and bacterial diseases, and may compete with native seabirds for cliffside burrows. Of particular concern is the conures’ ability to pass viable seed of highly invasive species, including Miconia calvescens, a tree which is found near the conures’ roosting/breeding areas. Information from the conures’ native range in South America suggests these birds can become established at elevations in excess of 3,000 meters, underscoring the potential for spreading invasive weeds into intact, native forests, and high value watersheds at upper elevations.