Case of Athens, Greece Social and Spatial Segregation of Municipality of Athens and Possible Solutions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greece I.H.T

Greece I.H.T. Heliports: 2 (1999 est.) GREECE Visa: Greece is a signatory of the 1995 Schengen Agreement Duty Free: goods permitted: 800 cigarettes or 50 cigars or 100 cigarillos or 250g of tobacco, 1 litre of alcoholic beverage over 22% or 2 litres of wine and liquers, 50g of perfume and 250ml of eau de toilet. Health: a yellow ever vaccination certificate is required from all travellers over 6 months of age coming from infected areas. HOTELS●MOTELS●INNS ACHARAVI KERKYRA BEIS BEACH HOTEL 491 00 Acharavi Kerkyra ACHARAVI KERKYRA GREECE TEL: (0663) 63913 (0663) 63991 CENTURY RESORT 491 00 Acharavi Kerkyra ACHARAVI KERKYRA GREECE TEL: (0663) 63401-4 (0663) 63405 GELINA VILLAGE 491 00 Acharavi Kerkyra ACHARAVI KERKYRA GREECE TEL: (0663) 64000-7 (0663) 63893 [email protected] IONIAN PRINCESS CLUB-HOTEL 491 00 Acharavi Kerkyra ACHARAVI KERKYRA GREECE TEL: (0663) 63110 (0663) 63111 ADAMAS MILOS CHRONIS HOTEL BUNGALOWS 848 00 Adamas Milos ADAMAS MILOS GREECE TEL: (0287) 22226, 23123 (0287) 22900 POPI'S HOTEL 848 01 Adamas, on the beach Milos ADAMAS MILOS GREECE TEL: (0287) 22286-7, 22397 (0287) 22396 SANTA MARIA VILLAGE 848 01 Adamas Milos ADAMAS MILOS GREECE TEL: (0287) 22015 (0287) 22880 Country Dialling Code (Tel/Fax): ++30 VAMVOUNIS APARTMENTS 848 01 Adamas Milos ADAMAS MILOS GREECE Greek National Tourism Organisation: Odos Amerikis 2b, 105 64 Athens Tel: TEL: (0287) 23195 (0287) 23398 (1)-322-3111 Fax: (1)-322-2841 E-mail: [email protected] Website: AEGIALI www.araianet.gr LAKKI PENSION 840 08 Aegiali, on the beach Amorgos AEGIALI AMORGOS Capital: Athens Time GMT + 2 GREECE TEL: (0285) 73244 (0285) 73244 Background: Greece achieved its independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1829. -

21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS SECTION Tel.: 2103202049, Fax: 2103226371

LIST OF BANK BRANCHES (BY HEBIC) 30/06/2015 BANK OF GREECE HEBIC BRANCH NAME AREA ADDRESS TELEPHONE NUMBER / FAX 0100001 HEAD OFFICE SECRETARIAT ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS SECTION tel.: 2103202049, fax: 2103226371 0100002 HEAD OFFICE TENDER AND ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS PROCUREMENT SECTION tel.: 2103203473, fax: 2103231691 0100003 HEAD OFFICE HUMAN ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS RESOURCES SECTION tel.: 2103202090, fax: 2103203961 0100004 HEAD OFFICE DOCUMENT ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS MANAGEMENT SECTION tel.: 2103202198, fax: 2103236954 0100005 HEAD OFFICE PAYROLL ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS MANAGEMENT SECTION tel.: 2103202096, fax: 2103236930 0100007 HEAD OFFICE SECURITY ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS SECTION tel.: 2103202101, fax: 210 3204059 0100008 HEAD OFFICE SYSTEMIC CREDIT ATHENS CENTRE 3, Amerikis, 102 50 ATHENS INSTITUTIONS SUPERVISION SECTION A tel.: 2103205154, fax: …… 0100009 HEAD OFFICE BOOK ENTRY ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS SECURITIES MANAGEMENT SECTION tel.: 2103202620, fax: 2103235747 0100010 HEAD OFFICE ARCHIVES ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS SECTION tel.: 2103202206, fax: 2103203950 0100012 HEAD OFFICE RESERVES ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS MANAGEMENT BACK UP SECTION tel.: 2103203766, fax: 2103220140 0100013 HEAD OFFICE FOREIGN ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS EXCHANGE TRANSACTIONS SECTION tel.: 2103202895, fax: 2103236746 0100014 HEAD OFFICE SYSTEMIC CREDIT ATHENS CENTRE 3, Amerikis, 102 50 ATHENS INSTITUTIONS SUPERVISION SECTION B tel.: 2103205041, fax: …… 0100015 HEAD OFFICE PAYMENT ATHENS CENTRE 3, Amerikis, 102 50 ATHENS SYSTEMS OVERSIGHT SECTION tel.: 2103205073, fax: …… 0100016 HEAD OFFICE ESCB PROJECTS CHALANDRI 341, Mesogeion Ave., 152 31 CHALANDRI AUDIT SECTION tel.: 2106799743, fax: 2106799713 0100017 HEAD OFFICE DOCUMENTARY ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. -

Registration Certificate

1 The following information has been supplied by the Greek Aliens Bureau: It is obligatory for all EU nationals to apply for a “Registration Certificate” (Veveosi Engrafis - Βεβαίωση Εγγραφής) after they have spent 3 months in Greece (Directive 2004/38/EC).This requirement also applies to UK nationals during the transition period. This certificate is open- dated. You only need to renew it if your circumstances change e.g. if you had registered as unemployed and you have now found employment. Below we outline some of the required documents for the most common cases. Please refer to the local Police Authorities for information on the regulations for freelancers, domestic employment and students. You should submit your application and required documents at your local Aliens Police (Tmima Allodapon – Τμήμα Αλλοδαπών, for addresses, contact telephone and opening hours see end); if you live outside Athens go to the local police station closest to your residence. In all cases, original documents and photocopies are required. You should approach the Greek Authorities for detailed information on the documents required or further clarification. Please note that some authorities work by appointment and will request that you book an appointment in advance. Required documents in the case of a working person: 1. Valid passport. 2. Two (2) photos. 3. Applicant’s proof of address [a document containing both the applicant’s name and address e.g. photocopy of the house lease, public utility bill (DEH, OTE, EYDAP) or statement from Tax Office (Tax Return)]. If unavailable please see the requirements for hospitality. 4. Photocopy of employment contract. -

The Hellenic Culture Centre Athens & Santorini Island, Greece

ERASMUS STUDENT PLACEMENTS THE HELLENIC CULTURE CENTRE ATHENS & SANTORINI ISLAND, GREECE WHO/ WHERE: A. The Hellenic Culture Centre www.hcc.edu.gr , founded in 1995, is one of the first non formal education institutions that offered Greek as a foreign/second language courses. It has an expertise in Language Teacher Training programmes. The aims of the institution are to promote language learning and language teaching and to contribute to adult education and intercultural education methodology. Has been involved in different national and EU projects on intercultural education, teacher training, cultural exchanges, e-learning. The Hellenic Culture Centre offers four internship posts for Erasmus students, for its offices in Athens and Santorini island, Greece: 1. Marketing coordinator To coordinate and implement a Marketing programme for new students recruitment, especially through the Internet, to work on the website, to upload materials and create newsletters, to translate texts into her/ his mother tongue 2. EU funding assistant To assist in developing proposals for EU funded projects under the Life Long Learning Programme, and to assist in implement projects that are on the way (monitor printing and production of materials, monitor on time implementation of events, monitor on time delivery of products/ deliverables, monitor expenses according to budget), to evaluate proposals and provide feedback. 3. E-learning expert To develop the e-learning platform of HCC. To coordinate the social networks of HCC. To create didactic materials for e-learning. To work on e-learning projects and develop new projects 4. Cultural Officer To develop a cultural programme in Athens & in Santorini complementary to the language programme, to develop training materials for cultural presentations (in English), to accompany students to cultural visits. -

NEW EOT-English:Layout 1

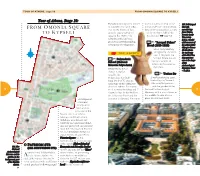

TOUR OF ATHENS, stage 10 FROM OMONIA SQUARE TO KYPSELI Tour of Athens, Stage 10: Papadiamantis Square), former- umental staircases lead to the 107. Bell-shaped FROM MONIA QUARE ly a garden city (with villas, Ionian style four-column propy- idol with O S two-storey blocks of flats, laea of the ground floor, a copy movable legs TO K YPSELI densely vegetated) devel- of the northern hall of the from Thebes, oped in the 1920’s - the Erechteion ( page 13). Boeotia (early 7th century suburban style has been B.C.), a model preserved notwithstanding 1.2 ¢ “Acropol Palace” of the mascot of subsequent development. Hotel (1925-1926) the Athens 2004 Olympic Games A five-story building (In the photo designed by the archi- THE SIGHTS: an exact copy tect I. Mayiasis, the of the idol. You may purchase 1.1 ¢Polytechnic Acropol Palace is a dis- tinctive example of one at the shops School (National Athens Art Nouveau ar- of the Metsovio Polytechnic) Archaeological chitecture. Designed by the ar- Resources Fund – T.A.P.). chitect L. Kaftan - 1.3 tzoglou, the ¢Tositsa Str Polytechnic was built A wide pedestrian zone, from 1861-1876. It is an flanked by the National archetype of the urban tra- Metsovio Polytechnic dition of Athens. It compris- and the garden of the 72 es of a central building and T- National Archaeological 73 shaped wings facing Patision Museum, with a row of trees in Str. It has two floors and the the middle, Tositsa Str is a development, entrance is elevated. Two mon- place to relax and stroll. -

May 2019 Dear Guests, This Is a Small List of Recommendations and Useful Information for You

www.svacropolis.com Last update: May 2019 Dear Guests, This is a small list of recommendations and useful information for you. It is by no means an exhaustive list as there are too many places to eat, drink and sight-see than we could possibly put down. Rather, this is a list of places that we enjoy and that our guests seem to like. We find that our guests like to discover things themselves. After all, is that not a great part of the joy of traveling? To discover new experiences and places. Just click on the underlined letters (link) to see information concerning whatever you are reading. We wish you a wonderful stay, and we hope you love Athens! Lucy & Andreas ACROPOLIS & OTHER SITES https://etickets.tap.gr/: The official site to purchase tickets online for the Acropolis and slopes, The Temple of Olympian Zeus, Kerameikos, Ancient Agora, Roman Agora, Adrians Library and Aristotle's School. Once you access the site in the left-hand corner there are the letters EΛ|EN; click on the EN for English. MUSEUMS THE ACROPOLIS MUSEUM, Dionysiou Areopagitou 15, Athens 117 42 Summer season hours (1/4 – 31/10) Winter season hours (1/11 – 31/3) Monday 8:00 - 16:00 Monday – Thursday 9:00 - 17:00 Tuesday – Sunday 8:00 – 20:00 Friday 9:00 - 22:00 Friday 8:00 a.m. – 22:00 Saturday – Sunday 9:00 a.m. – 20:00 last admission 30 minutes before closing time Closed: 1 January, Greek Orthodox Easter Sunday, 1 May, 25 and 26 December Good Friday: opens 12:00 to 18:00, Easter Saturday: opens 8:00 to 15:00 On August Full Moon and European Night of Museums, the Museum operates until midnight. -

The Hellenic Police and the Racist Crime Through the “Golden Dawn” Case-File

THE HELLENIC POLICE AND THE RACIST CRIME REPORT DRAFTED BY CIVIL ACTION LAWYER THANASIS KAMPAGIANNIS THROUGH THE “GOLDEN WITH THE SUPPORT OF HUMANRIGHTS360 TEAM DAWN” CASE-FILE © Tatiana Bolari / Eurokinissi CONTENTS Ι. Preamble 03 ΙΙ. Introduction 04 ΙΙI. Methodology -Structure 05 IV. Racist Crime and its punishment in the law 07 V. Findings of RVRN’s reports regarding the attitude of prosecution authorities. 12 VI. The indexing of cases of racist violence through the Golden Dawn case 17 VII. Trends and practices in the attitude of prosecution authorities - Comparative evaluation 56 VIII. Final Conclusions 62 THE HELLENIC POLICE AND THE RACIST CRIME 03 crime that organizations are pointing Ι. PREAMBLE out for years. In addition, the racist motive is investigated inadequately by the Greek Police, even in salient cases, criminal load is systemically underes- timated, and huge delays take place HumanRights360 while focusing on during the collection of evidence and the recording and combatting racist fulfillment of cases. Thanasis Kampa- crimes, has highlighted -beside the giannis, lawyer of the civil action of the profound positive changes in anti-rac- Egyptian fishermen in Golden Dawn’s ist legislation- the continuation of trial, has many times highlighted the delays in the investigation of crimes need to investigate the way in which which are motivated from prejudice: prosecution authorities in Greece relevant Authorities do not always have dealt with criminal actions that follow prosecution ex officio for every occurred with a racist -

Athens Metro Lines Development Plan and the European Union Transport and Networks

Kifissia M t . P e Zefyrion Lykovrysi KIFISSIA n t LEGEND e l i Metamorfosi KAT METRO LINES NETWORK Operating Lines Pefki Nea Penteli LINE 1 Melissia PEFKI LINE 2 Kamatero MAROUSSI LINE 3 Iraklio Extensions IRAKLIO Penteli LINE 3, UNDER CONSTRUCTION NERANTZIOTISSA OTE AG.NIKOLAOS Nea LINE 2, UNDER DESIGN Filadelfia NEA LINE 4, UNDER DESIGN IONIA Maroussi IRINI PARADISSOS Petroupoli Parking Facility - Attiko Metro Ilion PEFKAKIA Nea Vrilissia Ionia ILION Aghioi OLYMPIAKO "®P Operating Parking Facility STADIO Anargyri "®P Scheduled Parking Facility PERISSOS Nea PALATIANI Halkidona SUBURBAN RAILWAY NETWORK SIDERA Suburban Railway DOUK.PLAKENTIAS Anthousa ANO Gerakas PATISSIA Filothei "®P Suburban Railway Section also used by Metro o Halandri "®P e AGHIOS HALANDRI l P "® ELEFTHERIOS ALSOS VEIKOU Kallitechnoupoli a ANTHOUPOLI Galatsi g FILOTHEI AGHIA E KATO PARASKEVI PERISTERI GALATSI Aghia . PATISSIA Peristeri P Paraskevi t Haidari Psyhiko "® M AGHIOS NOMISMATOKOPIO AGHIOS Pallini ANTONIOS NIKOLAOS Neo PALLINI Pikermi Psihiko HOLARGOS KYPSELI FAROS SEPOLIA ETHNIKI AGHIA AMYNA P ATTIKI "® MARINA "®P Holargos DIKASTIRIA Aghia PANORMOU ®P KATEHAKI Varvara " EGALEO ST.LARISSIS VICTORIA ATHENS ®P AGHIA ALEXANDRAS " VARVARA "®P ELEONAS AMBELOKIPI Papagou Egaleo METAXOURGHIO OMONIA EXARHIA Korydallos Glyka PEANIA-KANTZA AKADEMIA GOUDI Nera "®P PANEPISTIMIO MEGARO MONASTIRAKI KOLONAKI MOUSSIKIS KORYDALLOS KERAMIKOS THISSIO EVANGELISMOS ZOGRAFOU Nikea SYNTAGMA ANO ILISSIA Aghios PAGRATI KESSARIANI Ioannis ACROPOLI NEAR EAST Rentis PETRALONA NIKEA Tavros Keratsini Kessariani SYGROU-FIX KALITHEA TAVROS "®P NEOS VYRONAS MANIATIKA Spata KOSMOS Pireaus AGHIOS Vyronas s MOSCHATO Peania IOANNIS o Dafni t Moschato Ymittos Kallithea ANO t Drapetsona i PIRAEUS DAFNI ILIOUPOLI FALIRO Nea m o Smyrni Y o Î AGHIOS Ilioupoli DIMOTIKO DIMITRIOS . -

Greece Info on Asylum Process, Law Legal Advice Medical Assistance Housing, Shelter Food, Social Support, Work Education Fb Support Groups

GREECE INFO ON ASYLUM PROCESS, LAW LEGAL ADVICE MEDICAL ASSISTANCE HOUSING, SHELTER FOOD, SOCIAL SUPPORT, WORK EDUCATION FB SUPPORT GROUPS http://www.asylumineurope. http://www.unhcr.org/greece.html Praksis http://www.housingrightswatch.org/page/state- EEDDA - Greek Committee For International http://www.eua.be/activities-services/eua- https://www.facebook. org/reports/country/greece http://www.praksis.gr/enFacebook57 Stournari housing-rights-7 Democratic Solidarity campaigns/refugees-welcome-map com/groups/OasisRhodes/permalink/170728036 Str,104 32 Athens www.eedda.gr27 Themistokleous str., 10677 9563728/ Email: infopraksis [dot] grTel: +30 21 05 20 52 00 Athens, Greece Fax: + 30 52 05 201 Tel: +30 21 03 81 30 52 Email: [email protected] Contact Person: Marie Lavrentiadou http://www.loc.gov/law/help/refugee-law/greece. The Greek Forum of Refugees https://vimeo.com/224051475 https://m.facebook.com/oniro.squat/ Praksis http://ec.europa. https://m.facebook.com/oniro.squat/ php www.refugees.gr/en/9-13 Gravias Str, 10678 http://www.praksis.gr/enFacebook57 Stournari eu/education/policy/migration_en Athens Str,104 32 Athens Tel: +30 21 30 28 29 76 or +30 69 48 40 89 28 Email: infopraksis [dot] grTel: +30 21 05 20 52 00 Email: [email protected] Fax: + 30 52 05 201 https://www.refugee.info/greece/ Aitima “BABEL” Day Centre Praksis Solidarity Now Center offers employment DIKTIO – Network of Social Support to https://www.facebook.com/mobileinfoteam/ www.aitima.grTripou Str 4, Athens 117 41 72 I. Drosopoulou streetGR -112 57 AthensTel: http://www.praksis.gr/enFacebook57 Stournari support- contact- 210 822 0883, address is Immigrants and Refugees Tel: +30 21 09 24 16 77 0030 210 8616280, 8616266 Fax: 0030 210 Str,104 32 Athens Domokou 2 (Junction of Domokou, Philadelphias (Mo-Fri from 17-20), free courses of Greek Email: [email protected] 8616102E-mail: [email protected] Web: http: Email: infopraksis [dot] grTel: +30 21 05 20 52 00 and Samou Streets, 2nd floor) language (Mo-Fr 18-20) and computer. -

Cultural Heritage in the Realm of the Commons: Conversations on the Case of Greece

CHAPTER 10 Commoning Over a Cup of Coffee: The Case of Kafeneio, a Co-op Cafe at Plato’s Academy Chrysostomos Galanos The story of Kafeneio Kafeneio, a co-op cafe at Plato’s Academy in Athens, was founded on the 1st of May 2010. The opening day was combined with an open, self-organised gather- ing that emphasised the need to reclaim open public spaces for the people. It is important to note that every turning point in the life of Kafeneio was somehow linked to a large gathering. Indeed, the very start of the initiative, in September 2009, took the form of an alternative festival which we named ‘Point Defect’. In order to understand the choice of ‘Point Defect’ as the name for the launch party, one need only look at the press release we made at the time: ‘When we have a perfect crystal, all atoms are positioned exactly at the points they should be, for the crystal to be intact; in the molecular structure of this crystal everything seems aligned. It can be, however, that one of the atoms is not at place or missing, or another type of atom is at its place. In that case we say that the crystal has a ‘point defect’, a point where its struc- ture is not perfect, a point from which the crystal could start collapsing’. How to cite this book chapter: Galanos, C. 2020. Commoning Over a Cup of Coffee: The Case of Kafeneio, a Co-op Cafe at Plato’s Academy. In Lekakis, S. (ed.) Cultural Heritage in the Realm of the Commons: Conversations on the Case of Greece. -

Athens Guide

ATHENS GUIDE Made by Dorling Kindersley 27. May 2010 PERSONAL GUIDES POWERED BY traveldk.com 1 Top 10 Athens guide Top 10 Acropolis The temples on the “Sacred Rock” of Athens are considered the most important monuments in the Western world, for they have exerted more influence on our architecture than anything since. The great marble masterpieces were constructed during the late 5th-century BC reign of Perikles, the Golden Age of Athens. Most were temples built to honour Athena, the city’s patron goddess. Still breathtaking for their proportion and scale, both human and majestic, the temples were adorned with magnificent, dramatic sculptures of the gods. Herodes Atticus Theatre Top 10 Sights 9 A much later addition, built in 161 by its namesake. Acropolis Rock In summer it hosts the Athens Festival (see Festivals 1 As the highest part of the city, the rock is an ideal and Events). place for refuge, religion and royalty. The Acropolis Rock has been used continuously for these purposes since Dionysus Theatre Neolithic times. 10 This mosaic-tiled theatre was the site of Classical Greece’s drama competitions, where the tragedies and Propylaia comedies by the great playwrights (Aeschylus, 2 At the top of the rock, you are greeted by the Sophocles, Euripides) were first performed. The theatre Propylaia, the grand entrance through which all visitors seated 15,000, and you can still see engraved front-row passed to reach the summit temples. marble seats, reserved for priests of Dionysus. Temple of Athena Nike (“Victory”) 3 There has been a temple to a goddess of victory at New Acropolis Museum this location since prehistoric times, as it protects and stands over the part of the rock most vulnerable to The Glass Floor enemy attack. -

Athens Strikes & Protests Survival Guide Budget Athens Winter 2011 - 2012 Beat the Crisis Day Trip Delphi, the Navel of the World Ski Around Athens Yes You Can!

Hotels Restaurants Cafés Nightlife Sightseeing Events Maps ATHENS Strikes & Protests Survival guide Budget Athens Winter 2011 - 2012 Beat the crisis Day trip Delphi, the Navel of the world Ski around Athens Yes you can! N°21 - €2 inyourpocket.com CONTENTS CONTENTS 3 ESSENTIAL CITY GUIDES Contents The Basics Facts, habits, attitudes 6 History A few thousand years in two pages 10 Districts of Athens Be seen in the right places 12 Budget Athens What crisis? 14 Strikes & Protests A survival guide 15 Day trip Antique shop Spend a day at the Navel of the world 16 Dining & Nightlife Ski time Restaurants Best resorts around Athens 17 How to avoid eating like a ‘tourist’ 23 Cafés Where to stay Join the ‘frappé’ nation 28 5* or hostels, the best is here for you 18 Nightlife One of the main reasons you’re here! 30 Gay Athens 34 Sightseeing Monuments and Archaeological Sites 36 Acropolis Museum 40 Museums 42 Historic Buildings 46 Getting Around Airplanes, boats and trains 49 Shopping 53 Directory 56 Maps & Index Metro map 59 City map 60 Index 66 A pleasant but rare Athenian view athens.inyourpocket.com Winter 2011 - 2012 4 FOREWORD ARRIVING IN ATHENS he financial avalanche that started two years ago Tfrom Greece and has now spread all over Europe, Europe In Your Pocket has left the country and its citizens on their knees. The population has already gone through the stages of denial and anger and is slowly coming to terms with the idea that their life is never going to be the same again.