Case 1:17-Cv-01791-RMC Document 21 Filed 11/06/17 Page 1 of 32

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Innovation in Magazine Media 2016-2017 World Report

INNOVATION IN MAGAZINE MEDIA IN MAGAZINE INNOVATION INNOVATION IN MAGAZINE MEDIA 2016-2017 WORLD REPORT A SURVEY BY INNOVATION MEDIA CONSULTING FOR FIPP – THE NETWORK FOR GLOBAL MEDIA JUAN SEÑOR 2016-2017 WORLD REPORT WORLD 2016-2017 JOHN WILPERS JUAN ANTONIO GINER EDITORS 46 DISTRIBUTION MODELS INNOVATION IN MAGAZINE MEDIA 2016-2017 How to distribute your content where your readers are Get over it: You don’t need to own the platform where your content appears if you can spread it wider and more profitably elsewhere… with two big caveats INNOVATION IN MAGAZINE MEDIA 2016-2017 DISTRIBUTION MODELS 47 f you were a musician and could sell more mu- sic through a third party than through a record label, would you put your music up on iTunes? If you were a movie or television producer and could get more consumers to watch your I movies or TV shows by licensing them to a powerful distributor like Netflix, would you give up sole control of their distribution? And if you were a clothing, shoe or hand- bag manufacturer and could sell more product through outlets and online sites, would you follow the lead of big brand companies like Jimmy Choo, Gucci, Prada, Versace, and Rober- to Cavalli and put your products on Amazon? Doesn’t it follow then, in a time when total control of the means of distribution is less rel- evant to a company’s mission, that it makes sense for publishers to spread their content wider, get exposure to new subscribers, and increase profits by putting their content on outside distribution platforms which offer billions of readers? Absolutely… If two conditions are met. -

ECF 56 Third Amended Complaint

Case 1:19-cv-00160-RMC Document 56 Filed 09/19/19 Page 1 of 27 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE .DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA TAMRYN SPRUTLL and JACOB SUNDSTROM, individually and on behalf of all those similarly situated, Plaintiffs, Civil Action No.: l:l 9-cv-00160-RMC vs. Class Action Complaint VOX MEDIA, INC, Jury Trial Demanded Defendants. THIRD AMENDED COMPLAINT I. INTRODUCTION 1. Plaintiffs Tainryn Spruill and Jacob Sundstrom (together, "Plaintiffs") bring this class and representative action against Defendant Vox Media, Inc., ("Defendant' or "Vox") on behalf of themselves and all other former and current paid content contributors for Vox's sports blogging network. and flagship property SB :Nation in California, who Vox classified as independent contractors. S.B Nation operates over 300 team. sites dedicated to publishing written articles, videos, and other content on professional and college sports. Each team. site posts daily coverage on games, statistics, player trades, and culture. 'The more traffic the team sites attract, the more advertising revenue Vox generates. Vox pays Plaintiffs and similarly situated class members ("Content Contributors") a small monthly stipend to create and edit the written, video, and. audio content on these team sites. Content Contributors' posts are the core of Vox's business. 2. .During the entire class period, Vox. uniformly and consistently misclassfied Content Contributors —including job titles such as Site Manager, Associate Editor, Managing Editor, Deputy Editor, and Contributor — as independent contractors in order to avoid its duties 1 764747.8 Case 1:19-cv-00160-RMC Document 56 Filed 09/19/19 Page 2 of 27 and obligations owed to employees under California law and to gain. -

Innovation in Magazine Media 2016-2017 World Report a Survey by Innovation Media Consulting for Fipp – the Network for Global Media

INNOVATION IN MAGAZINE MEDIA IN MAGAZINE INNOVATION INNOVATION IN MAGAZINE MEDIA 2016-2017 WORLD REPORT A SURVEY BY INNOVATION MEDIA CONSULTING FOR FIPP – THE NETWORK FOR GLOBAL MEDIA JUAN SEÑOR 2016-2017 WORLD REPORT WORLD 2016-2017 JOHN WILPERS JUAN ANTONIO GINER EDITORS INNOVATION IN MAGAZINE MEDIA 2016-2017 CONTENTS 3 90 WELCOME FROM FIPP’S CHRIS LLEWELLYN: 5 What’s the biggest obstacle to change? EDITORS’ NOTE 6 A how-to guide to innovation CULTURE 10 TREND SPOTTING 90 Innovation starts How to spot (and profit with the leader from) a trend with digital ADVERTISING 18 VIDEO 104 How to solve the How to make great videos ad blocking crisis that do not break the bank SMALL DATA 32 OFFBEAT 116 How to use data to solve How to inspire, entertain, all your problems provoke and surprise DISTRIBUTION MODELS 46 ABOUT INNOVATION 128 How to distribute your content Good journalism is where your readers are good business MICROPAYMENTS 58 ABOUT FIPP 130 10 How micropayments can Join the conversation deliver new revenue, new readers and new insights MOBILE 72 How to make mobile the 72 monster it should be for you NATIVE ADVERTISING 82 How to succeed at native advertising 116 ISBN A SURVEY AND ANALYSIS BY 978-1-872274-81-2 Innovation in Magazine Media 2016-2017 World Report - print edition 978-1-872274-82-9 Innovation in Magazine Media 2016-2017 World Report - digital edition ON BEHALF OF Paper supplied with thanks to UPM First edition published 2010, 7th edition copyright © 2016 Printed on UPM Finesse Gloss 300 g/m² and by INNOVATION International Media Consulting Group and FIPP. -

2010 Annual Report

2010 ANNUAL REPORT Table of Contents Letter from the President & CEO ......................................................................................................................5 About The Paley Center for Media ................................................................................................................... 7 Board Lists Board of Trustees ........................................................................................................................................8 Los Angeles Board of Governors ................................................................................................................ 10 Media Council Board of Governors ..............................................................................................................12 Public Programs Media As Community Events ......................................................................................................................14 INSIDEMEDIA Events .................................................................................................................................14 PALEYDOCFEST ......................................................................................................................................20 PALEYFEST: Fall TV Preview Parties ...........................................................................................................21 PALEYFEST: William S. Paley Television Festival ......................................................................................... 22 Robert M. -

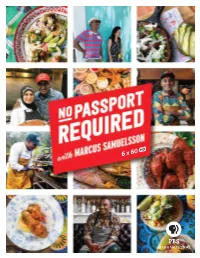

6 X 60 Hosted by Renowned Chef Marcus Samuelsson, No Passport Required Is a New Six-Part Series That Takes Viewers on an Inspiring Journey Across the U.S

6 x 60 Hosted by renowned chef Marcus Samuelsson, No Passport Required is a new six-part series that takes viewers on an inspiring journey across the U.S. to explore and celebrate the wide-ranging diversity of immigrant traditions and cuisine woven into American food and culture. Each week, Marcus—an immigrant himself—visits a new city to discover the dynamic and creative ways a particular community has made its mark. A vibrant portrait of America today, 6 x 60 No Passport Required features musicians, poets, chefs, business owners, contact artists, community leaders and home cooks who have enhanced the nation’s culture and cuisine. Tom Koch, Vice President PBS International From Detroit, where Marcus meets Middle Eastern immigrants who call 10 Guest Street the city home, to the Ethiopian community in Washington, D.C., No Passport Boston, MA 02135 USA Required showcases how food can bring Americans—old and new—together TEL: +1.617.208.0735 around the table. In New Orleans, Marcus learns how Vietnamese culinary [email protected] traditions have fully integrated into the fabric of the city, taking center stage pbsinternational.org with long-established French and African influences. In New York, he’s shown how the Indo-Guyanese culture thrives in a small enclave of Queens, and how this one community has taken the best of its Indian, Caribbean and colonial heritage and incorporated those influences into its customs and cuisine. In Chicago, Marcus ventures into the city’s Mexican neighborhoods and discovers their impact on the area’s food and cultural landscape. Going beyond the borders of South Beach, he also meets with members of Miami’s proud Haitian community. -

Season 2 of NO PASSPORT REQUIRED with Marcus Samuelsson Explores the Food and Culture of America’S Immigrant Communities

Season 2 of NO PASSPORT REQUIRED with Marcus Samuelsson Explores the Food and Culture of America’s Immigrant Communities Full Schedule and Episode Descriptions CHEFS MARCUS AND VIVIAN: A TASTE OF WHAT’S NEXT Friday, December 13, 8:30-9:00 p.m. ET Chefs Vivian Howard and Marcus Samuelsson have been traveling around the country to better understand immigrant foodways. While in Los Angeles, the two chefs visit Grand Central Market to meet new friends that contribute to the richness of L.A.’s food scene. Vivian’s new series SOMEWHERE SOUTH premieres on PBS in 2020. NO PASSPORT REQUIRED - Season 2 Preview “Seattle” – Friday, December 13, 9:00-10:00 p.m. ET Marcus explores Seattle’s thriving Filipino community, learning about their longstanding connection to the city and meeting young Filipino-American chefs who are bringing their passion to the city's vibrant food scene. Along the way, he discovers how their cuisine combines the unique flavors of the island nation’s complex history, which includes Chinese, Spanish, Japanese and American influences. Come along as Marcus visits a variety of restaurants — from food trucks to a trendy speakeasy to cutting-edge fine dining establishments — and samples delicacies including chicken adobo, oyster ceviche, pork blood stew and a unique but tasty cheesecake made with purple yam. “Los Angeles” – Monday, January 20, 9:00-10:00 p.m. ET - Season 2 Premiere Marcus visits Los Angeles, where the largest Armenian community outside of the homeland thrives in the foothills north of downtown L.A. Resilient and entrepreneurial, Armenians are scattered across the world, and Marcus meets Armenians from Russia, Lebanon, Syria, Ethiopia and Egypt. -

Comscore Study Finds Advertising on Premium Publisher Sites Drives Higher Ad Effectiveness

July 14, 2016 comScore Study Finds Advertising on Premium Publisher Sites Drives Higher Ad Effectiveness Premium Publishers are 3x More Effective in Driving Mid-Funnel Brand Lift Metrics Such as Favorability, Consideration and Intent to Recommend RESTON, Va., July 14, 2016 /PRNewswire/ -- comScore (NASDAQ: SCOR) today announced the publication of its latest report, The Halo Effect: How Advertising on Premium Publishers Drives Higher Ad Effectiveness. The research and resulting study examines the branding effectiveness of digital display ads appearing on Digital Content Next (DCN)* member sites compared to non-member sites. The study revealed that this segment of publishers delivered significantly better branding effectiveness results across a number of measures. The primary driver of this increased effectiveness is the 'halo effect' of the contextual environment in which the ads are seen. With the rapid growth of programmatic advertising in recent years, concerns have arisen about whether digital ad impressions are becoming increasingly commoditized. While more efficient in some ways, this approach can sometimes overlook other important factors that determine advertising effectiveness, such as media quality. comScore sought to understand the extent to which media quality mattered in driving advertising effectiveness, and the value of premium inventory. Key findings from the study include: Display ads on DCN premium publisher sites had an average of 67% higher brand lift than non-DCN publishers, confirming that premium sites deliver premium performance. Premium publishers are more than 3x more effective in driving mid-funnel brand lift metrics such as favorability, consideration and intent to recommend. Premium publisher effectiveness is driven in part by higher viewability rates which include lower levels of invalid traffic. -

New Parking Structure Gets City Approval

. • ., --:: ': • 1" • ';... t,: - • • .... ':,.:. <i. ....... J:,. '" .c, .,." ~. • J I- • . "" .... - ,i Orchids subject of study for Chico State professor California State University, Chico Chico, California Volume 22, Issue 6 ' Page 19 Wednesday, March 8, 1989 :,: -:':...> . ,. ~, New parking New offensive coach structure gets ..... , named for football team .r'·~ , Larry Korpitz, senior member of the Uni city approval versity of Wyoming football coaching staff, was named the new offensive coordinator for By SHERI WARNER the Chico State University Wildcat football ,.-.- Staff Wl'iLer team Tuesday, according to a press release from the Chico State public affairs depart The Chico City Council last week approved Chico State ment. University's plan to create a three-to-four-deck parking The vacancy in the position was created garage on the existing surface lot on West First and Ivy streets. by the promotion of fonner Wildcat defensive But the Council, by a 4 tg 3 vote, rejected the coordinator Gary Houser to the head coach university's proposal for another lot that would have re ing position when fonner Wildcat head coach quired the razing of the College Park neighborhood located Mike BelIotti accepted the post of offensive between Warner Street and the Esken and Mechoopda resi coordinator at the University of Oregon. Kor dence halls. pitz wilI start March 15. The lot on West First and Ivy, which currently holds "My primary re,L~on for coming here is 208 spaces, is expected to hold approximately 600 to 800 because Coach Houser needed someone to spaces after decks are added, said Gordon Fercho, vice come in and install an offense that worked," president of business and administration at Chico State. -

February 1, 2019 Mr. Jim Bankoff, Chief Executive Officer Vox Media

TY CLEVENGER P.O. Box 20753 Brooklyn, New York 11202-0753 telephone: 979.985.5289 [email protected] facsimile: 979.530.9523 Texas Bar No. 24034380 February 1, 2019 Mr. Jim Bankoff, Chief Executive Officer Vox Media, Inc. 1201 Connecticut Avenue, 11th Floor Washington, DC 20036 Mr. Marty Moe, President Vox Media, Inc. 1201 Connecticut Avenue, 11th Floor Washington, DC 20036 Jane Coaston, Senior Politics Reporter Vox Media, Inc. 1201 Connecticut Avenue, 11th Floor Washington, DC 20036 Re: Edward Butowsky Mr. Bankoff, Mr. Moe, and Ms. Coaston: I write on behalf of Ed Butowsky pursuant to TEXAS CIV. PRAC. & REM. CODE §73.055 to request the retraction of defamatory statements made about Mr. Butowsky. I have attached two articles by Ms. Coaston that appeared on the Vox website on April 19, 2018 and October 1, 2018, respectively, and I have highlighted numerous false and defamatory statements about Mr. Butowsky. Contrary to Ms. Coaston's statements, Mr. Butwosky has not lied about anything, nor has he knowingly concocted false stories. And he certainly has not acted with any malice toward Joel and Mary Rich. On his behalf, I must demand that you retract and repudiate the false statements identified in the attached articles. If I do not receive a response or notice of retraction prior to February 15, 2019, we will proceed with litigation. Thank you for your attention to these matters. Sincerely, Ty Clevenger Seth Rich’s parents are taking their fight against Fox News to court Is Fox News liable for spreading a conspiracy theory? By Jane Coaston [email protected] Updated Apr 19, 2018, 2:38pm EDT Mary Rich, the mother Seth Rich, gives a press conference in the Bloomingdale neighborhood of Washington DC, on August 1, 2016. -

The Reconstruction of American Journalism

The Reconstruction of American Journalism A report by Leonard Downie, Jr. Michael Schudson Vice President at Large Professor The Washington Post Columbia University Professor, Arizona State University Graduate School of Journalism October 20, 2009 The Reconstruction of American Journalism By Leonard Downie, Jr. and Michael Schudson American journalism is at a transformational moment, in which the era of dominant newspapers and influential network news divisions is rapidly giving way to one in which the gathering and distribution of news is more widely dispersed. As almost everyone knows, the economic foundation of the nation’s newspapers, long supported by advertising, is collapsing, and newspapers themselves, which have been the country’s chief source of independent reporting, are shrinking— literally. Fewer journalists are reporting less news in fewer pages, and the hegemony that near-monopoly metropolitan newspapers enjoyed during the last third of the twentieth century, even as their primary audience eroded, is ending. Commercial television news, which was long the chief rival of printed newspapers, has also been losing its audience, its advertising revenue, and its reporting resources. Newspapers and television news are not going to vanish in the foreseeable future, despite frequent predictions of their imminent extinction. But they will play diminished roles in an emerging and still rapidly changing world of digital journalism, in which the means of news reporting are being reinvented, the character of news is being reconstructed, -

Nurnberger Appointed Principal Tom Tighe Selected Chairman Friends

South Amboy-Sayreville Times December 16, 2017 1 Kanecke Irish Two Police Officers Person Of The Year Promoted In Patricia Attardi Kanecke was selected by the South Amboy Irish-American Sayreville Association as Irish Person of the Year for The Sayreville Police Dept. recently 2018. Congratulations Patti, and best of promoted Frank Olchaskey and Amy Noble luck always! to the rank of sergeant. Police Chief John Zebrowski said that both were previously Nurnberger acting sergeants. Olchaskey is currently working in the Uniformed Division, and Appointed Principal Noble works in the Identification Bureau. The Sayreville Board of Education South Amboy Mayor Fred Henry (3rd from right) and Council members (l-r) Tom Reilly, Christine Congratulations and continued success! approved the appointment of new Dwight Noble, and Brian McLaughlin, join the Firefighters from Mechanicsville Fire Co. after they won Best D. Eisenhower Elementary School principal Decorated Truck at the City’s annual Holiday Parade and Tree Lighting. (Photo by Brian Stratton) Scott Nurnberger who began his new position on Nov. 1. Nurnberger was previously 76th Anniversary of the Attack on Pearl Harbor vice principal of Samsel Upper Elementary School. Congratulations and best of luck! Friends Of Rose Cornhole Tournament The 2nd Annual Friends of Rose Co- Ed Cornhole Tournament will be held at Victorian Hall, Knights of Columbus #2061, Washington Rd., Parlin on Sat. Feb. 24, 2018. Registration begins at 4 p.m. Cost is $50 per male/female team. There will be prizes, bar, and music. To sign up call Keith Rybak 732-261-1025 or Eric Hausmann 908-420- 5470. -

Secret Google Project Accused of Using Ad Data to Lift Sales

P2JW102000-6-A00100-17FFFF5178F ADVERTISEMENT Wonderingwhatitfeels like to finally roll over your old 401k? Find outhow our rolloverspecialists canhelpyou getthe ball rolling on page R10. ****** MONDAY,APRIL 12, 2021 ~VOL. CCLXXVII NO.84 WSJ.com HHHH $4.00 Last week: DJIA 33800.60 À 647.39 2.0% NASDAQ 13900.19 À 3.1% STOXX 600 437.23 À 1.2% 10-YR. TREASURY À 16/32 , yield 1.664% OIL $59.32 g $2.13 EURO $1.1902 YEN 109.67 Matsuyama Wins Masters, in a First for a Japanese Man CEO Pay What’s News Climbs In Year Business&Finance Of Vast EO paysurged in 2020, Ca year of historic busi- nessupheaval, awrenching Upheaval labor market formanywork- ersand unprecedented chal- lenges formanyleaders. A1 Median compensation Google foryearsoperated a reaches $13.7 million secret program that used past bid datainthe company’sad for leaders at 300 of exchange to allegedly give the biggest companies itsown ad-buying system an advantageovercompetitors, BY THEO FRANCIS according to acourt filing. A1 GES AND KRISTIN BROUGHTON Fed chief Powell said IMA the U.S. economy appears CEO paysurgedin2020,a to be at an inflection point, GETTY year of historic businessup- with output and job growth heaval,awrenching labor mar- poised to accelerateaslong ketfor manyworkersand chal- as the pandemic retreats. A2 EHRMANN/ lenges formanyleaders. Median payfor the chief ex- Medline Industries is ex- MIKE FITTING: Hideki Matsuyama dons the greenjacket afterwinning the 85th Masters tournament at the Augusta National Golf ecutives of morethan 300 of ploring asale that could value Club in Augusta,Ga., on Sunday.