Explaining Abuse of “Child Witches” in Africa Powerful Witchbusters in Weak States Steve Snow, Wagner College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fear and Faith: Uncertainty, Misfortune and Spiritual Insecurity in Calabar, Nigeria Ligtvoet, I.J.G.C

Fear and faith: uncertainty, misfortune and spiritual insecurity in Calabar, Nigeria Ligtvoet, I.J.G.C. Citation Ligtvoet, I. J. G. C. (2011). Fear and faith: uncertainty, misfortune and spiritual insecurity in Calabar, Nigeria. s.l.: s.n. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/22696 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) License: Leiden University Non-exclusive license Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/22696 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). Fear and Faith Uncertainty, misfortune and spiritual insecurity in Calabar, Nigeria Inge Ligtvoet MA Thesis Supervision: ResMA African Studies Dr. Benjamin Soares Leiden University Prof. Mirjam de Bruijn August 2011 Dr. Oka Obono Dedicated to Reinout Lever † Hoe kan de Afrikaanse zon jouw lichaam nog verwarmen en hoe koelt haar regen je af na een tropische dag? Hoe kan het rode zand jouw voeten nog omarmen als jij niet meer op deze wereld leven mag? 1 Acknowledgements From the exciting social journey in Nigeria that marked the first part of this work to the long and rather lonely path of the final months of writing, many people have challenged, advised, heard and answered me. I have to thank you all! First of all I want to thank Dr. Benjamin Soares, for being the first to believe in my fieldwork plans in Nigeria and for giving me the opportunity to explore this fascinating country. His advice and comments in the final months of the writing have been really encouraging. I’m also grateful for the supervision of Prof. Mirjam de Bruijn. From the moment she got involved in this project she inspired me with her enthusiasm and challenged me with critical questions. -

Written Statement* Submitted by International Humanist and Ethical Union, a Non-Governmental Organization in Special Consultative Status

United Nations A/HRC/45/NGO/126 General Assembly Distr.: General 21 September 2020 English only Human Rights Council Forty-fifth session 14 September–2 October 2020 Agenda item 3 Promotion and protection of all human rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development Written statement* submitted by International Humanist and Ethical Union, a non-governmental organization in special consultative status The Secretary-General has received the following written statement which is circulated in accordance with Economic and Social Council resolution 1996/31. [20 August 2020] * Issued as received, in the language(s) of submission only. GE.20-12164(E) A/HRC/45/NGO/126 Witchcraft-related human rights abuses In some communities, to be labelled a ‘witch’ is tantamount to receiving a death sentence. An alternative fate might involve banishment, stigmatization, or torture. The reasons driving witchcraft allegations vary across countries and beliefs, but some features are widely shared. These are acts born out of anger and powerlessness at the inability to manage the seemingly random negative forces governing one’s life. Sometimes these attacks are legitimised and encouraged by religious leaders or spiritual ‘healers’ for their own financial gain. Victims typically belong to marginalised groups with limited resources to fight back against the accusations. Exact numbers of victims are unknown, as many instances go unreported and unmonitored by official bodies. It is estimated that each year there are at least thousands of cases of witchcraft accusations globally, often with fatal consequences. During one week in 2019, in India alone, a boy murdered his aunt after accusing her of witchcraft; a man was set on fire after a 10-year-old girl fell sick; and six men alleged to be witches had their teeth pulled out and were force-fed excrement. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Dick Clifford\My Documents

Meet Leo Igwe from Nigeria, he has been awarded a speaking tour of Australia by the CSIRO and the Canberra Skeptics thanks to a grant from Science Week. He is well known as a fighter for Justice and for his campaigns against witchcraft accusers, incurring the wrath and assaults from priestess Helen Ukpabio’s mob, and arrest by the police but he continues to rescue children accused of witch craft and holds meetings and seminars against superstition. ADELAIDE MEETINGS (If you are interstate ask your local Skeptics Society) Tuesday 30th August 6 pm. ABC, Studio 520, 85 North East Road, Collinswood . Bus Stop 13, routes 271, 273 (from stop E2 Currie Street), Routes 204 205 (F) 206 (F) 208 209 (F) (from King William St.) Parking in Rosetta St. opposite ABC main Building Entrance at Cnr of Gallway Ave. & N.E. Rd. Doors open 5.30 pm. Gold coin entry. Booking essential: Please book by Email to [email protected] or by phone 8255 9508 stating your name, return address, (net or phone), which day you are booking, and how many you are booking for. Note: Elderly citizens should not climb the stairs to the balcony but should insist on a ground floor seat. Meeting closes at 7.30 pm. After the meeting you can attend a dinner across the street at the Walkers Arms smorgasbord, 7.30 session, but you must book separately, 8344 8022 When booking with Walkers Arms say “with Leo Igwe group” The dinner costs $25.90 + 10% gst +drinks. Those with a pensioners card can claim 10% discount. -

Reason and Superstition in Uganda

OP-ED and not those who want, for example, regimented, controlled, regulated. By much to guarantee a better life for us more and better housing developments whom, one might ask? By other indi- all as to place the responsibility for and means of transportation. But the viduals who supposedly know what is seeking such a life with individuals. We bottom line of the chorus of complaints important for the rest to do. now need to decide what to pursue with about modernity seems, in fact, to be Criticisms of modernity are voiced all the great tools that modernity has nothing other than that individuals are in terms of concern for the interests or produced. We can go seriously astray in better equipped now than ever before good of the community, the public, the that task. But it is no longer credible to to pursue their very own chosen goals. nation, or humanity, as opposed to the claim that ordinary folks are to be treat- Technology helps us to strive for our selfish pursuits of individuals. But in ed like little children who must look to chosen goals: we can travel better to the most cases, the conflict isn’t between others—others who are just as capable places where we wish to go; we can keep public and private interests but between of making mistakes—to make us behave alive longer and thus do more of what we one private interest and another. properly. want to do; we can receive information Environmentalists, for example, more rapidly than ever before, so we can have no special understanding of what Tibor R. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/02/2021 01:52:23PM Via Free Access

Chapter 15 Sacred Surplus and Pentecostal Too-Muchness: The Salvation Economy of African Megachurches Asonzeh Ukah 1 Introduction [E]verything is plastic, even life itself david chidester 2018:178 The beginning of the Christian Church is usually associated with the coming of the Holy Spirit upon the frightened followers of Jesus as narrated in Acts of the Apostle (Chapter 2). After Peter summoned courage to speak to the gathered “multitude”, the story concludes that many of those who heard the word, be- lieved and were baptised and were added to the church numbered “about three thousand” (Acts 2:41). Were this base community to be meeting weekly for liturgical purposes, it would have constituted the first Christian mega- church. However, for many reasons, the early church grew only slowly and met in small groups in members’ homes and often clandestinely. The experience and the phenomenon which the concept of ‘megachurch’ encapsulates is as old as Christianity itself; nevertheless, the coinage of ‘megachurch’, like many other nomenclatures with the prefix ‘mega’ (such as megacity, megaton), is recent and of American provenance, and probably first used in a scholarly con- text in the late 1970s (Dubios 1978). Mega – originally derived from the Greek megas meaning huge, and/or powerful – may have been the shortened form of one million (as a base of measurement), signifying an extremely large scale or excellent quality or sheer quantity. The megachurch denotes an excellent, great and successful church organisation or group. Its proliferation in Africa in recent decades signifies the appeal of its products to a large section of the African Christian population; its practices and organisational structure revolve around a princi- pal charismatic figure believed to be a supplier of sacred or salvation goods who is cast in the mould of a profit-driven spiritual entrepreneur. -

Sanctuaries for Witch-Hunt Victims in Northern Ghana

Felix Riedel: SANCTUARIES FOR WITCH-HUNT VICTIMS IN NORTHERN GHANA SANCTUARIES FOR WITCH-HUNT VICTIMS IN NORTHERN GHANA Felix Riedel Abstract: Witch-hunts in Ghana’s Northern Region mainly occur among neighbours and members of the extended family. Factors triggering accusations are disease, death and accidents. With many exceptions, the accused are mainly postmenopausal women. Accusers include children, women and men alike. Witch-hunts only occasionally target specific behaviour or deviancy: they are registered as accidental and “unjust” by almost all victims. Most accusations disrupted productive relationships and reaped no benefit for the accusers. The victims are often tortured in order to produce confessions. The accusers rely on dreams for singling out the accused, while the latter are then forced to chicken- and potion-ordeals at various shrines to determine their guilt or innocence. Exorcisms include potions and shaving. Today, about 800 victims of witchcraft-accusations live in nine sanctuaries for witchhunt-victims to dodge further accusations and lynching. While diverse in character, eight of the nine sanctuaries adhere to an earth-shrine-complex typical for Northern Ghana and beyond. Social work with the victims and educational campaigns by NGOs are well-tried and promising, but governmental malpractice and media attention have thus far reaped mixed results. Keywords: Witch-hunts, Ghana, Earth-Shrines, Konkomba, Sanctuaries for Witch-hunt Victims Modern Africa: Politics, History and Society 2018 | Volume 6, Issue 1, pages 29–60 29 https://doi.org/10.26806/modafr.v6i1.220 Modern Africa: Politics, History and Society | 2018 | Volume 6, Issue 1 Map. Locations of the sanctuaries for witch-hunt victims and of the shrine Tongnaab in Tengzug.1 Introduction Sanctuaries for victims of witch-hunts exist in the DRC, Ghana, Malawi, South-Africa, Nigeria, Burkina Faso, Togo, and Burkina Faso (Riedel 2012). -

HIV/AIDS and Terministic Screens: a Pentadic Interrogation of the Claims to Origin

HIV/AIDS and Terministic Screens: A Pentadic Interrogation of the Claims to Origin, Cure, and Economics in the Rhetoric of Yahya Jammeh A dissertation presented to the faculty of the Scripps College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Prosper Y. Tsikata August 2015 © 2015 Prosper Y. Tsikata. All Rights Reserved. This dissertation titled HIV/AIDS and Terministic Screens: A Pentadic Interrogation of the Claims to Origin, Cure, and Economics in the Rhetoric of Yahya Jammeh by PROSPER Y. TSIKATA has been approved for the School of Communication Studies and the Scripps College of Communication by Benjamin R. Bates Professor of Communication Studies Scott Titsworth Dean, Scripps College of Communication ii Abstract TSIKATA, PROSPER Y., Ph.D., August 2015, Communication Studies HIV/AIDS the Terministic Screens: A Pentadic Interrogation of Claims to Origin, Cure, and Economics in the Rhetoric of Yahya Jammeh Director of Dissertation: Benjamin R. Bates In this dissertation, I interrogated the claims to origin and cure of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and the Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) and the economics of Antiretroviral Drugs (ARVs) in the rhetoric of the Gambian President, Yahya Jammeh. This study was motivated by two research questions: (1) How does Jammeh’s claims fit into or depart from the known HIV/AIDS and ARVs discourses; and (2) to what extent can Kenneth Burke’s terministic screens, in conjunction with the dramatistic pentad, be applied to Jammeh’s claims to distill the values embedded in them for Jammeh’s motives and their articulation? Regarding the origin of the HIV virus, I unearthed three competing theories—the natural transfer, the conspiratorial, and the Congo-jungle accident. -

Report West African Humanist Conference, Ghana, November 2012 Written by Gea Meijers

Report West African Humanist Conference, Ghana, November 2012 written by Gea Meijers From 23 to 25 November humanists gathered in Accra, Ghana, to reflect on humanist action in West Africa. The conference led to the kick-start of a regional humanist network in West Africa and offered a rich discussion of the objectives and role of organized humanism in West Africa. The conference was organized by the Humanist Association of Ghana and IHEYO, the youth section of the International Humanist and Ethical Union (IHEU). The conference started with a public conference on Friday 23 November that inspired speakers and participants to speak out about the challenges for humanism in West Africa, especially in Ghana. This day reflected on the role of organized humanism as an alternative to religion. Answers were formulated to questions such as ‘how should humanists approach religious beliefs and practices?’ and ‘what would be the agenda for humanism promoting human rights?’. Around 40 people participated in the conference that was held in the SSNIT Guest House, in the centre of Accra. The conference was structured into four sessions with nine speakers and a chair of the day. Introduction session: humanism as lifestance and practice in West Africa Daniel Addae of the Humanist Association of Ghana opened the conference with a welcome address in which he explained the history of organized humanism in Ghana, starting in the ‘80s with the rationalist centre. In 2012, the Humanist Association of Ghana was spontaneously formed in a burst of enthusiasm. The group offers a community for humanist minded people to speak out freely, with at the centre of all discussions, the issue of the appalling state of human rights in our society. -

Justice and Human Rights in the African Imagination

There is nobody more qualifed to do justice to the imbrications of liter- ature and ethical commitment in Africa than Chielozona Eze. With this well-accomplished and erudite book, Eze consolidates his position as the leading scholar of African ethics in literary contexts. Students and scholars of culture and philosophy will fnd this book an invaluable model for their own work. — Cajetan Iheka, Yale University, author of Naturalizing Africa: Ecological Violence, Agency, and Postcolonial Resistance in African Literature Justice is often associated with an ideal state of affairs. Although this is an important way to approach the question of justice, realizing justice requires more than thinking about ideals. We must consider the aspect of what hap- pens in situations where injustice is enthroned. This means to think about the damage done to individuals and social and political institutions due to the prolonged experience of injustice. Chielozona Eze offers in this book an outstanding study of these issues. He takes the reader on a journey that cul- minates in a clear understanding of the connection between political organ- ization and the contexts of justice. Anyone interested in original ideas about justice, based on re-imagination of African conceptual resources, should read this book. — Uchenna Okeja, PhD. Professor of philosophy, Rhodes University Justice and Human Rights in the African Imagination Justice and Human Rights in the African Imagination is an interdisciplinary reading of justice in literary texts and memoirs, flms, and social anthropo- logical texts in postcolonial Africa. Inspired by Nelson Mandela and South Africa’s robust achievements in human rights, this book argues that the notion of restorative justice is in- tegral to the proper functioning of participatory democracy and belongs to the moral architecture of any decent society. -

Humanist Voices: Collection Ii

1 2 In-Sight Publishing 3 HUMANIST VOICES: COLLECTION II 4 IN-SIGHT PUBLISHING Publisher since 2014 Published and distributed by In-Sight Publishing Fort Langley, British Columbia, Canada www.in-sightjournal.com Copyright © 2019 by Scott Douglas Jacobsen In-Sight Publishing established in 2014 as a not-for-profit alternative to the large commercial publishing houses who dominate the publishing industry. In-Sight Publishing operates in independent and public interests rather than in dependent and private ones, and remains committed to publishing innovative projects for free or low-cost while electronic and easily accessible for public domain consumption within communal, cultural, educational, moral, personal, scientific, and social values, sometimes or even often, deemed insufficient drivers based on understandable profit objectives. Thank you for the download of this ebook, your consumption, effort, interest, and time support independent and public publishing purposed for the encouragement and support of academic inquiry, creativity, diverse voices, freedom of expression, independent thought, intellectual freedom, and novel ideas. © 2014-2019 by Scott Douglas Jacobsen. All rights reserved. Original appearance in or submission to, or first published in parts by or submitted to, Humanist Voices. Not a member or members of In-Sight Publishing, 2017-2019 This first edition published in 2019 No parts of this collection may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized, in any form, or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented or created, which includes photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher or the individual co-author(s) or place of publication of individual articles. -

DOWNLOAD 2018 Annual Report File Type

At the heart of a vibrant global humanist community Annual Report 2018 Contents Foreword 2 Introduction 3 The Objectives of Humanists International 4 Global highlights 6 Our people 10 Key figures in 2018 12 Highlights 14 Successful and sustainable Member Organizations in every part of the world 18 Member Organizations which are networked together as a coordinated global movement 22 International and regional government policies are shaped by our policy agenda 26 Sufficient reputation, financial and human resources, and administrative effectiveness to achieve our goals 33 CONTENTS 1 Foreword 2018 was an extraordinary year of change for Humanists International We began to see the results of our decision in recent global south, but also to more organizations which years to invest more resources into supporting the are more established but could stand to benefit growth and development of humanism in the global greatly from being helped to reach the “next step” south and also to make our central organization more of their development. We want to do what we can representative of global diversity. This was a very to share good practice, and source new training and welcome development, a strong personal mission for support options for all our members. me, and is thanks to the generosity of our Member I would like to take this opportunity to thank you Organizations, supporters and donors. all for your support of Humanists International. Meanwhile, behind the scenes, we were working to Thank you, prepare the organization for its change in name, a full re-brand, and a new website built from the ground up to serve the needs of Humanists International and our members. -

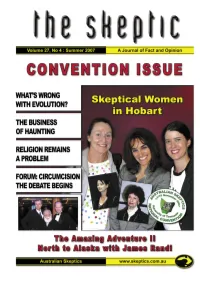

The Skeptic Volume 27 (2007) No 4.Pdf

Summer 2007, Vol 27, No 4 Feature Articles 7. Convention Round-up 34. The Haunted Sanitorium Barry Willims Karen Stollznow 10. David Hume: A skeptic’s sceptic 38. Witches and Africans James Allan Leo Igwe 14. The ‘Robustness’ of Climate Change 40. Can a Scientist Rely on Induction? Garth Paltridge Dan Carmody 17. Anomalistic Psychology 42. A Tale of Medical Horror Krissy Wilson Peter Willims 20. Religion Remains a Problem 50. Enquiring Minds Want to Know ... Neville Buch Ed Curnow 27. Report: A Ship of Skeptics 52. Space Travel Musings Richard Saunders Rex Newsome 30. What’s Wrong with Evolution? 52. Circumcision Facts Trump Anti-circ Myths Brian Baxter Brian Morris Regular Items Forum 4. Editorial — Times of Change 60. To Snip or Not to Snip Barry Williams 63. The Power of Prayer 6. Around the Traps 64. Climate Change Bunyip 66. Letters News 68. Notices 46. WA Skeptics Awards Cover art by Richard Saunders Editorial ISSN 0726-9897 Editor Barry Williams Associate Editor Changing Karen Stollznow Contributing Editors Tim Mendham Steve Roberts Technology Consultants Times Richard Saunders Eran Segev Chief Investigator Ian Bryce All correspondence to: Australian Skeptics Inc PO Box 268 Roseville NSW 2069 Australia (ABN 90 613 095 379 ) Contact Details Tel: (02) 9417 2071 Fax: (02) 9417 7930 e-mails: [email protected] Web Pages Australian Skeptics www.skeptics.com.au No Answers in Genesis™ www.noanswersingenesis.org.au the Skeptic is a journal of fact and opinion, published four times per year by Australian Skeptics Inc. Views and opinions expressed in articles and letters in the Skeptic are those of the authors, and are not necessar- ily those of Australian Skeptics Inc.