Dream Deferred? Democracy and Good Governance: an Assessment of the Findings of Uganda's Country Self- Assessment Report Under

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UGANDA COUNTRY REPORT October 2004 Country

UGANDA COUNTRY REPORT October 2004 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Uganda Report - October 2004 CONTENTS 1. Scope of the Document 1.1 - 1.10 2. Geography 2.1 - 2.2 3. Economy 3.1 - 3.3 4. History 4.1 – 4.2 • Elections 1989 4.3 • Elections 1996 4.4 • Elections 2001 4.5 5. State Structures Constitution 5.1 – 5.13 • Citizenship and Nationality 5.14 – 5.15 Political System 5.16– 5.42 • Next Elections 5.43 – 5.45 • Reform Agenda 5.46 – 5.50 Judiciary 5.55 • Treason 5.56 – 5.58 Legal Rights/Detention 5.59 – 5.61 • Death Penalty 5.62 – 5.65 • Torture 5.66 – 5.75 Internal Security 5.76 – 5.78 • Security Forces 5.79 – 5.81 Prisons and Prison Conditions 5.82 – 5.87 Military Service 5.88 – 5.90 • LRA Rebels Join the Military 5.91 – 5.101 Medical Services 5.102 – 5.106 • HIV/AIDS 5.107 – 5.113 • Mental Illness 5.114 – 5.115 • People with Disabilities 5.116 – 5.118 5.119 – 5.121 Educational System 6. Human Rights 6.A Human Rights Issues Overview 6.1 - 6.08 • Amnesties 6.09 – 6.14 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.15 – 6.20 • Journalists 6.21 – 6.24 Uganda Report - October 2004 Freedom of Religion 6.25 – 6.26 • Religious Groups 6.27 – 6.32 Freedom of Assembly and Association 6.33 – 6.34 Employment Rights 6.35 – 6.40 People Trafficking 6.41 – 6.42 Freedom of Movement 6.43 – 6.48 6.B Human Rights Specific Groups Ethnic Groups 6.49 – 6.53 • Acholi 6.54 – 6.57 • Karamojong 6.58 – 6.61 Women 6.62 – 6.66 Children 6.67 – 6.77 • Child care Arrangements 6.78 • Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) -

The Applicant Col Rtd Dr. Kizza Besigye Filled This Application by Notice of Motion Under Article 23 (6) of the Constitution Of

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA IN THE HIGH COURT OF UGANDA AT KAMPALA CRIMINAL APPLICATION NO. 83 OF 2016 (ARISING FROM MOR-OO-CR-AA-016/2016 AND NAK-A-NO.14/2016) COL (RTD) DR. KIZZA BESIGYE:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: APPLICANT VERSUS UGANDA::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: RESPONDENT. BEFORE: HON JUSTICE MR. MASALU MUSENE RULING The applicant Col Rtd Dr. Kizza Besigye filled this application by Notice of Motion under Article 23 (6) of the Constitution of Uganda, section 14 of the Trial on Indictments Act, cap 23 and rule 2 of the Judicature (criminal procedure)(applications rules S.I 13 -8) and all applicable laws. It is an application for bail pending trial. The applicant was represented by Mr. Ernest Kalibala together with Mr. Frederick Mpaga while the state was represented by M/S Florence Akello, principal state attorney and Mr. Brian Kalinaki also principal state attorney from the office of the Director of Public Prosecutions. The grounds in support of the application are outlined in the affidavit of the applicant, Col (Rtd) Kizza Besigye of Buyinja Zone, Nangabo sub-county, Kasangati in Wakiso district. In summary, they are as follows; 1. That on 13th May 2016, the applicant was charged with the offence of treason in the Chief Magistrates Court of Moroto at Moroto and remanded in custody. 1 2. That on 18th May 2016, the applicant was charged with the offence of treason in the Chief Magistrates court of Nakawa at Nakawa and remanded in custody. 3. That the applicant is a 60 year old responsible and respectable citizen of Uganda, a retired colonel in the Uganda Peoples Defence Forces and former presidential candidate in the 2016 presidential elections where he represented the Forum for Democratic Change, a dully registered political party. -

Uganda Date: 30 October 2008

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: UGA33919 Country: Uganda Date: 30 October 2008 Keywords: Uganda – Uganda People’s Defence Force – Intelligence agencies – Chieftaincy Military Intelligence (CMI) – Politicians This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide information on the Uganda Peoples Defence Force (Ugandan Army)/Intelligence Agencies and a branch of the Army called Chieftaincy Military Intelligence, especially its history, structure, key officers. Please provide any information on the following people: 2. Noble Mayombo (Director of Intelligence). 3. Leo Kyanda (Deputy Director of CMI). 4. General Mugisha Muntu. 5. Jack Sabit. 6. Ben Wacha. 7. Dr Okungu (People’s Redemption Army). 8. Mr Samson Monday. 9. Mr Kyakabale. 10. Deleted. RESPONSE 1. Please provide information on the Uganda Peoples Defence Force (Ugandan Army)/Intelligence Agencies and a branch of the Army called Chieftaincy Military Intelligence, especially its history, structure, key officers. The Uganda Peoples Defence Force UPDF is headed by General Y Museveni and the Commander of the Defence Force is General Aronda Nyakairima; the Deputy Chief of the Defence Forces is Lt General Ivan Koreta and the Joint Chief of staff Brigadier Robert Rusoke. -

The Trials and Tribulations of Rtd. Col. Dr. Kizza Besigye and 22 Others

The Role of the General Court Martial in the Administration of Justice in Uganda THE TRIALS AND TRIBULATIONS OF RTD. COL. DR. KIZZA BESIGYE AND 22 OTHERS A Critical Evaluation of the Role of the General Court Martial in the Administration of Justice in Uganda Ronald Naluwairo Copyright © Human Rights &Peace Centre, 2006 ISBN 9970-511-00-8 HURIPEC Working Paper No.1. October, 2006 The Role of the General Court Martial in the Administration of Justice in Uganda The Role of the General Court Martial in the Administration of Justice in Uganda Table of Contents Acknowledgments ....................................................................................ii Summary of the Report and Policy Recommendations.......................... iii List of Acronyms.......................................................................................vi I. INTRODUCTION....................................................................................1 II. BACKGROUND TO THE TRIALS OF BESIGYE & 22 OTHERS.........3 III. THE LAW GOVERNING THE GENERAL COURT MARTIAL............12 A. Establishment, Composition and Tenure ...........................................13 B. Quorum and Decision Making............................................................14 C. Jurisdiction ....................................................................................... 14 D. Guarantees for the Right to a Fair Hearing and a Just Trial ..............17 IV. THE RELATIONSHIP WITH CIVILIAN COURTS..............................19 V. EVALUATION OF THE ROLE OF THE GENERAL COURT -

The Republic of Uganda in the Supreme

5 THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA IN THE SUPREME COURT OF UGANDA AT KAMPALA PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION PETITION NO. O1 OF 2016 (CORAM: KATUREEBE, C.J, TUMWESIGYE, KISAAKYE, 10 ARACH AMOKO, NSHIMYE, MWANGUSYA,OPIO-AWERI, MWONDHA, TIBATEMWA-EKIRIKUBINZA, JJ.SC.) AMAMA MBABAZI …………………………………….PETITIONER VERSUS 15 YOWERI KAGUTA MUSEVENI ……………. 1stRESPONDENT ELECTORAL COMMISSION ……………… 2ndRESPONDENT THE ATTORNEY GENERAL ………………… 3rd RESPONDENT PROFESSOR OLOKA ONYANGO & 8 ORS………..AMICI 20 CURIAE DETAILED REASONS FOR THE JUDGMENT OF THE COURT The Petitioner, who was one of the candidates in the presidential 25 election that was held on the 18th February, 2016 petitioned the 1 5 Supreme Court under the Constitution, the Presidential Elections Act, 2000 and the Electoral Commission Act, 1997 (hereinafterreferred to as the PEA and the ECA, respectively). He challenged the result of the election and sought a declaration that Yoweri Kaguta Museveni, the 1st Respondent, was not 10 validly elected and an order that the election be annulled. On the 31st March 2016, we delivered our decision in line with the Constitutional timeline imposed on the Court to render its judgment within 30 days from the date of filing the petition. We were not, however, in a position to give detailed reasons for our 15 findings and conclusion. We found that the 1st Respondent was validly elected as President in accordance with Article 104 of the Constitution and Section 59 of the PEA. Accordingly, we unanimously dismissed the petition. We made no order as to costs. 20 We promised to give the detailed reasons at a later date, which we now give in this judgment. Background The 18thFebruary 2016 General Elections were the 3rd since the re-introduction of multiparty politics in Uganda as the country 25 shifted from the movement system. -

Politics and the Demographic Shift: the Role of the Opposition in Uganda

Africa Programme Meeting Summary Politics and the Demographic Shift: The Role of the Opposition in Uganda Speaker: Dr Kizza Besigye Leader, Forum for Democratic Change (FDC), Republic of Uganda Chair: Ben Shepherd Consulting Fellow, Africa Programme, Chatham House 9 September 2016 The views expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the speaker(s) and participants, and do not necessarily reflect the view of Chatham House, its staff, associates or Council. Chatham House is independent and owes no allegiance to any government or to any political body. It does not take institutional positions on policy issues. This document is issued on the understanding that if any extract is used, the author(s)/speaker(s) and Chatham House should be credited, preferably with the date of the publication or details of the event. Where this document refers to or reports statements made by speakers at an event, every effort has been made to provide a fair representation of their views and opinions. The published text of speeches and presentations may differ from delivery. © The Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2017. 10 St James’s Square, London SW1Y 4LE T +44 (0)20 7957 5700 F +44 (0)20 7957 5710 www.chathamhouse.org Patron: Her Majesty The Queen Chairman: Stuart Popham QC Director: Dr Robin Niblett Charity Registration Number: 208223 2 Politics and the Demographic Shift: The Role of the Opposition in Uganda Introduction This meeting summary provides an overview of an event held at Chatham House, on 9 September 2016, with Dr Kizza Besigye, leader of Uganda’s main opposition party, the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC). -

PRESS RELEASE Nairobi 16Th February 2016, for Immediate Release Contact: Njonjo Mue, Senior Advisor KPTJ [email protected] 07

PRESS RELEASE Nairobi 16th February 2016, for immediate release Contact: Njonjo Mue, Senior Advisor KPTJ [email protected] 0721308911 Kenyan Civil Society concerned about the diminishing Democratic Space in Uganda ahead of the February 2016 Elections. On Monday, 15 February 2016, Uganda’s police arrested Dr. Kizza Besigye, the presidential flag bearer for the main opposition party, the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC). Dr. Besigye is one of the eight presidential candidates cleared to contest for the Presidency in the upcoming General Election scheduled for 18 February 2016. Dr. Besigye’s arrest came only three days to the election polling day and two days ahead of the official closing of the campaign period for political parties. The information we have is that Dr. Besigye was arrested on his way to a campaign rally at Makerere University where his supporters had gathered. During his arrest police lobbed tear gas and water cannons at the peaceful supporters to disperse them. This provoked the crowd leading to commotion between the supporters and the security agencies, resulting in the death of one of the supporters, with many others sustaining injuries. The arrest and detention of Dr. Besigye which also led to a disruption of his political campaign, was a violation of the universal right of peaceful assembly, freedom of expression and freedom of association guaranteed by Articles, 19, 22 and 23 of International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; Articles 19, 20 and 21 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; and Articles 9-11 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights to which Uganda is a party. -

Uganda: Freedom in the World 2017 Country Report | Freedom House

Uganda: Freedom in the World 2017 Country Report | Freedom House https://freedomhouse.org/country/uganda/freedom-world/2017 While Uganda holds regular elections, their credibility has deteriorated over time, and the country has been ruled by the same party and president since 1986. The ruling party, the National Resistance Movement (NRM), retains power through the manipulation of state resources, intimidation by security forces, and politicized prosecutions of opposition leaders. Uganda’s civil society and media sectors remain vibrant, despite suffering sporadic legal and extralegal harassment and state violence. The LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) community remains under threat. In February, Uganda held deeply flawed general elections that featured harassment and violence against the opposition, among other abuses. President Yoweri Museveni of the ruling NRM was officially awarded another five-year term in office. In May, Kizza Besigye, the leading opposition presidential candidate, was charged with treason following months of arrests, detentions, and periods of house arrest. Legislation enacted in January contained ill-defined regulatory provisions for nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) that could allow government interference, and extralegal intimidation remained a serious challenge to civil society advocacy. In 2016, Uganda held its third general elections since the transition to a multiparty system in 2005. While incumbent president Museveni was reelected, the polls were marred by severe intimidation of voters and the opposition, the repeated arrest of presidential challenger Kizza Besigye, the use of state resources for the ruling party’s campaign, and significant delays in voting. The president signed the Non-Governmental Organisations (NGO) Act in January, despite criticism that its ambiguous language could be used to ban groups that challenge the government. -

College of Humanities and Social Sciences

MAKERERE UNIVERSITY P.O. Box 7062 Kampala, Uganda Tel: +256-414-543919 Arts Building Room 43 Email: [email protected] Web: www.mak.ac.ug Web: www.jocom.mak.ac.ug DEPARTMENT OF JOURNALISM AND COMMUNICATION 9th March 2018 Press Information LAUNCH OF THE ‘WORLD TRENDS IN FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION AND MEDIA DEVELOPMENT REPORT’ 2017/2018 The Department of Journalism and Communication Makerere University, in partnership with Oslo and Akershus University College of Applied Sciences, Norway, is set to launch a report on World Trends in Freedom of Expression and Media Development 2017/18. This event will take place on Wednesday 14th March 2018 at the Senate Telepresence center (Level 2), Senate Building, Makerere University, 2:00pm. The report, which covers the period 2012 to 2017, discusses freedom of expression across four key dimensions of media freedom, pluralism, independence and safety of journalists. It is intended as a tool for implementing the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which recognizes the importance of ensuring public access to information and protecting fundamental freedoms among its goals. As one of its observations, the report shows that media independence is weakening and the professional standards of journalism are being eroded by economic forces on the one hand and lack of recognition by political actors on the other. The report launch will be preceded by a panel discussion moderated by a top Journalist, Charles Mwanguhya. The panelists are: i) Prof. Goretti Linda Nassanga; Department of Journalism and Communication- Mak ii) Assoc. Prof. Fredrick Jjuuko from the School of Law- Mak iii) Daniel Kalinaki- Nation Media Group Below are their brief profiles: Prof. -

The Cotter Pin by Andrew Rice

AR-7 Sub-Saharan Africa Andrew Rice is a Fellow of the Institute studying life, politics and development in ICWA Uganda and environs. LETTERS The Cotter Pin By Andrew Rice JANUARY 1, 2003 Since 1925 the Institute of KAMPALA, Uganda—The sirens’ wail was getting louder. Outside the Nile Current World Affairs (the Crane- Hotel’s International Conference Center, the hexagonal slab of port-holed con- Rogers Foundation) has provided crete where three decades of Ugandan presidents have welcomed important visi- long-term fellowships to enable tors, the blue-uniformed honor guard stiffened to attention in the late-November outstanding young professionals heat. The ministers and generals took their places on the steps. Reporters pulled to live outside the United States out their notebooks, news photographers lifted their cameras to their shoulders. and write about international All eyes fixed on the front gates. The presidents were about to arrive. areas and issues. An exempt operating foundation endowed by A little after 10a.m., a pickup truck peeled through the gates, loaded with the late Charles R. Crane, the security officers, machine guns at the ready. A pair of motorcycle police followed, Institute is also supported by leading the way for the black Mercedes limousine. It glided to the front of the contributions from like-minded building and stopped. individuals and foundations. The doors of the limousine opened, and the presidents emerged. From one side, His Excellency Daniel Toroitich Arap Moi, president of Kenya, dressed in his customary fashion: a dark blue suit and a garish multicolored necktie. From TRUSTEES the other, His Excellency Yoweri Kaguta Museveni, president of Uganda, nattily Bryn Barnard attired as always. -

The Political Economy of Violence in Uganda's Masaka

Quest Journals Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science Volume 6 ~ Issue 11 (2018) pp.: 01-18 ISSN(Online) : 2321-9467 www.questjournals.org Research Paper Insecurty In Maska District –Publication Astate Of Insecurity(delete): The Political Economy Of Violence In Uganda’s Masaka District Nabukeera Madinah (Phd) Senior Lecturer Islamic University in Uganda Females’ CampusFaculty of Management Studies Department of Public Administration ABSTRACT:This article examines the problem of insecurity in Uganda in areas of Masaka district in the western part of the country. It provides a typology of the insecurity incidents which occurred in areas of Bukomansimbi, Lwengo, Rakai, Sembabule, Kalungu, Nyendo, Lyantonde districts and Kingo sub-county and examines the steps which government and other stakeholders have taken to address the problem. Using a qualitative approach, interviews were conducted in the affected areas with LCI chairpersons, locals and area members of parliament together with library research to explain why these measures have failed to reduce the high level of crime that takes place in and around the country. The article focuses on three related issues: the political economy of the Uganda state;catalysts for insecurity and the manner in which the government and other actors have sought to manage the country's insecurity situation. Received 17 October, 2018; Accepted 03 Novenber, 2018 © The author(s) 2018. Published with open access at www.questjournals.org I. OVER VIEW Colonial Economy The mid-19th Century was a period of Scramble and Partition of Africa. Whether African societies resisted or collaborated, by 1914 the whole of African continent had been put under colonial administration with exception of Ethiopia and Liberia. -

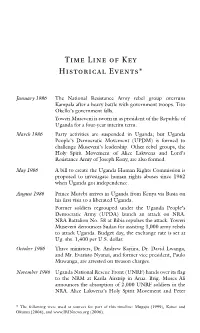

Time Line of Key Historical Events*

Time Line of Key Historical Events* January 1986 The National Resistance Army rebel group overruns Kampala after a heavy battle with government troops. Tito Okello’s government falls. Yoweri Museveni is sworn in as president of the Republic of Uganda for a four-year interim term. March 1986 Party activities are suspended in Uganda; but Uganda People’s Democratic Movement (UPDM) is formed to challenge Museveni’s leadership. Other rebel groups, the Holy Spirit Movement of Alice Lakwena and Lord’s Resistance Army of Joseph Kony, are also formed. May 1986 A bill to create the Uganda Human Rights Commission is proposed to investigate human rights abuses since 1962 when Uganda got independence. August 1986 Prince Mutebi arrives in Uganda from Kenya via Busia on his first visit to a liberated Uganda. Former soldiers regrouped under the Uganda People’s Democratic Army (UPDA) launch an attack on NRA. NRA Battalion No. 58 at Bibia repulses the attack. Yoweri Museveni denounces Sudan for assisting 3,000 army rebels to attack Uganda. Budget day, the exchange rate is set at Ug. shs. 1,400 per U.S. dollar. October 1986 Three ministers, Dr. Andrew Kayiira, Dr. David Lwanga, and Mr. Evaristo Nyanzi, and former vice president, Paulo Muwanga, are arrested on treason charges. November 1986 Uganda National Rescue Front (UNRF) hands over its flag to the NRM at Karila Airstrip in Arua. Brig. Moses Ali announces the absorption of 2,000 UNRF soldiers in the NRA. Alice Lakwena’s Holy Spirit Movement and Peter * The following were used as sources for part of this timeline: Mugaju (1999), Kaiser and Okumu (2004), and www.IRINnews.org (2006).