2013 Humanitarian Accountability Report Acronyms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti

Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti DISSERTATION ZUR ERLANGUNG DER GRADES DES DOKTORS DER PHILOSOPHIE DER UNIVERSTÄT HAMBURG VORGELEGT VON YASIN MOHAMMED YASIN from Assab, Ethiopia HAMBURG 2010 ii Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti by Yasin Mohammed Yasin Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (POLITICAL SCIENCE) in the FACULITY OF BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES at the UNIVERSITY OF HAMBURG Supervisors Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff HAMBURG 15 December 2010 iii Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my doctoral fathers Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit and Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff for their critical comments and kindly encouragement that made it possible for me to complete this PhD project. Particularly, Prof. Jakobeit’s invaluable assistance whenever I needed and his academic follow-up enabled me to carry out the work successfully. I therefore ask Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit to accept my sincere thanks. I am also grateful to Prof. Dr. Klaus Mummenhoff and the association, Verein zur Förderung äthiopischer Schüler und Studenten e. V., Osnabruck , for the enthusiastic morale and financial support offered to me in my stay in Hamburg as well as during routine travels between Addis and Hamburg. I also owe much to Dr. Wolbert Smidt for his friendly and academic guidance throughout the research and writing of this dissertation. Special thanks are reserved to the Department of Social Sciences at the University of Hamburg and the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) that provided me comfortable environment during my research work in Hamburg. -

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

The Impact of Existing and Proposed Irrigation Scheme on Hydrology Of

Addis Ababa University School of Graduate Studies Addis Ababa Institute of Technology The Impact of Existing and Proposed Irrigation scheme on Hydrology of lake Ziway A thesis Submitted and presented to the School of Graduate Studies of Addis Ababa University in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree of Master of Science in Civil & Environmental Engineering (Major in Hydraulic Engineering) By Daniel Fekadu Advisor Dr. Mebruk Mohammed Addis Ababa University October, 2016 The impact of existing and proposed irrigation scheme on Hydrology of lake Ziway 2016 Addis Ababa University School of Graduate Studies Addis Ababa Institute of Technology The Impact of Existing and Proposed Irrigation scheme on Hydrology of lake Ziway A thesis submitted and presented to the school of graduate studies of Addis Ababa University in partial fulfillment of the degree of Masters of Science in Civil Engineering (Major Hydraulic Engineering) By Daniel Fekadu Approval by Board of Examiners ---------------------------------------------------- ------------------ Advisor Signature ---------------------------------------------------- ------------------ Internal Examiner Signature ---------------------------------------------------- ------------------ External Examiner Signature ---------------------------------------------------- ------------------ Chairman (Department of Graduate Committee) Signature AAIT/SCEE 2 The impact of existing and proposed irrigation scheme on Hydrology of lake Ziway 2016 ABSTRACT Lake Ziway is located in Oromia Regional State near the Town of Ziway some 150 km south of Addis Ababa at the northern end of the southern Rift Valley. The lake covers an area of some 450 km2 at its average surface level of 1,636.12 m and has a maximum depth of 8 m. The two major rivers flowing to the lake are Meki and Katar Rivers and there is Bulbula river as an outflow from the lake. -

Nigella Sativa) at the Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia

Asian Journal of Agricultural Extension, Economics & Sociology 31(3): 1-12, 2019; Article no.AJAEES.47315 ISSN: 2320-7027 Assessment of Production and Utilization of Black Cumin (Nigella sativa) at the Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia Wubeshet Teshome1 and Dessalegn Anshiso2* 1Ethiopian Biodiversity Institute, Horticulture and Crop Biodiversity Directorate, P.O.Box 30726; Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. 2College of Economics and Management, Huazhong Agricultural University, No. 1 Shizishan Street, Hongshan District, Wuhan, 430070, Hubei, P.R. China. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration between both authors. Author WT managed the literature searches and participated in data collection. Author DA designed the study, performed the statistical analysis, wrote the protocol and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/AJAEES/2019/v31i330132 Editor(s): (1) Prof. Fotios Chatzitheodoridis, Department of Agricultural Technology-Division of Agricultural Economics, Technological Education Institute of Western Macedonia, Greece. Reviewers: (1) Lawal Mohammad Anka, Development Project Samaru Gusau Zamfara State, Nigeria. (2) İsmail Ukav, Adiyaman University, Turkey. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sdiarticle3.com/review-history/47315 Received 14 November 2018 Accepted 09 February 2019 Original Research Article Published 06 April 2019 ABSTRACT Background and Objective: Black cuminseed for local consumption and other importance, such as oil and oil rosin for medicinal purposes, export market, crop diversification, income generation, reducing the risk of crop failure and others made it as a best alternative crop under Ethiopian smaller land holdings. The objectives of this study were to examine factors affecting farmer perception of the Black cumin production importance, and assess the crop utilization purpose by smallholder farmers and its income potential for the farmers in two Districts of Bale zone of Oromia regional state in Ethiopia. -

Inter-Agency Field Mission Report – Siraro Woreda West Arsi Zone, Oromia Region 27-31 May 2020 GOAL, SCI, CDI, OCHA, UNICEF/ABH, ZDRMO and ZHD

Inter-agency field mission report – Siraro woreda West Arsi zone, Oromia Region 27-31 May 2020 GOAL, SCI, CDI, OCHA, UNICEF/ABH, ZDRMO and ZHD Balela 01 kebele, Kella IDP site in Siraro woreda, 27 May 2020 1. BACKGROUND According to zonal and woreda disaster risk management offices (DRMOs), in May 2019, a long-term Sidama-Oromo clan conflict escalated causing more than 170 casualties (including 40 fatalities), displacement of 36,000 people and destruction of around 600 homes in six kebeles along the administrative boundaries between Sidama and West Arsi zones. The escalation was preceded by a two-year deterioration of security situation between Sidama’s Hawassa Zuria, Bilate Zuria woredas and West Arsi’s Siraro woreda. Zonal and woreda authorities reported then new displacement to the Oromia regional DRMC (ODRMC) and key humanitarian partners.; Cconsequently, four rounds of emergency food were delivered to the IDPs. In the course of 2019, some 15,406 IDPs returned to their homes and 20,774 IDPs have remained with host community and scattered across six kebeles in Siraro woreda as follows: Page 1 of 8 Kebeles Number of IDPs Current locations 1. Shello Illacho 7,425 Host community 2. Shello Balela 4,860 Host community, and kebele office 3. Shello Abore 1,080 Host community 4. Balela 01 1,610 Host community 5. Onoko 3,519 Host community 6. Different kebeles 2,280 Host community (Kella,Bilito,Shasha,and Gayo) Total: 20,774 Source: Siraro woreda DRMO 2. SITUATION OVERVIEW The assessment team consulted around 200 IDPs residing in three clusters, from Finchaha area (from about 50 Gute or sub-kebele) in Shello Balela kebele. -

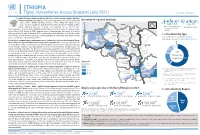

20210714 Access Snapshot- Tigray Region June 2021 V2

ETHIOPIA Tigray: Humanitarian Access Snapshot (July 2021) As of 31 July 2021 The conflict in Tigray continues despite the unilateral ceasefire announced by the Ethiopian Federal Government on 28 June, which resulted in the withdrawal of the Ethiopian National Overview of reported incidents July Since Nov July Since Nov Defense Forces (ENDF) and Eritrea’s Defense Forces (ErDF) from Tigray. In July, Tigray forces (TF) engaged in a military offensive in boundary areas of Amhara and Afar ERITREA 13 153 2 14 regions, displacing thousands of people and impacting access into the area. #Incidents impacting Aid workers killed Federal authorities announced the mobilization of armed forces from other regions. The Amhara region the security of aid Tahtay North workers Special Forces (ASF), backed by ENDF, maintain control of Western zone, with reports of a military Adiyabo Setit Humera Western build-up on both sides of the Tekezi river. ErDF are reportedly positioned in border areas of Eritrea and in SUDAN Kafta Humera Indasilassie % of incidents by type some kebeles in North-Western and Eastern zones. Thousands of people have been displaced from town Central Eastern these areas into Shire city, North-Western zone. In line with the Access Monitoring and Western Korarit https://bit.ly/3vcab7e May Reporting Framework: Electricity, telecommunications, and banking services continue to be disconnected throughout Tigray, Gaba Wukro Welkait TIGRAY 2% while commercial cargo and flights into the region remain suspended. This is having a major impact on Tselemti Abi Adi town May Tsebri relief operations. Partners are having to scale down operations and reduce movements due to the lack Dansha town town Mekelle AFAR 4% of fuel. -

World Bank Document

PROCUREMENT PLAN (Textual Part) Project information: Ethiopia, One WASH- Consolidated WASH Account (CWA) Project “Phase II”, P167794 Project Implementation agency: Water Development Commission (WDC) of Public Disclosure Authorized the Ministry of Water, Irrigation and Energy (MoWIE) Date of the Procurement Plan: August 28, 2019 Period covered by this Procurement Plan: September 2019 to August 2020. Preamble In accordance with paragraph 5.9 of the “World Bank Procurement Regulations for IPF Borrowers” (July 2016 revised August 2018) (“Procurement Regulations”) the Bank’s Systematic Tracking and Exchanges in Procurement (STEP) system will be used to prepare, clear and update Procurement Plans and conduct all procurement Public Disclosure Authorized transactions for the Project. This textual part along with the Procurement Plan tables in STEP constitute the Procurement Plan for the Project. The following conditions apply to all procurement activities in the Procurement Plan. The other elements of the Procurement Plan as required under paragraph 4.4 of the Procurement Regulations are set forth in STEP. The Bank’s Standard Procurement Documents: shall be used for all contracts subject to international competitive procurement and those contracts as specified in the Procurement Plan tables in STEP. Public Disclosure Authorized National Procurement Arrangements: In accordance with paragraph 5.3 of the Procurement Regulations, when approaching the national market (as specified in the Procurement Plan tables in STEP), the country’s own procurement procedures may be used. When the Borrower uses its own national open competitive procurement arrangements as set forth in Section 33(1)(a) from 35-48 of the Proclamation Number 649/2009 of the Ethiopian Federal Government Procurement and Property Administration Proclamation, such arrangements shall be subject to paragraph 5.4 of the Procurement Regulations and the following conditions. -

PDF Download

Integrated Blood Pressure Control Dovepress open access to scientific and medical research Open Access Full Text Article ORIGINAL RESEARCH Knowledge and Attitude of Self-Monitoring of Blood Pressure Among Adult Hypertensive Patients on Follow-Up at Selected Public Hospitals in Arsi Zone, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study This article was published in the following Dove Press journal: Integrated Blood Pressure Control Addisu Dabi Wake 1 Background: Self-monitoring of blood pressure (BP) among hypertensive patients is an Daniel Mengistu Bekele 2 important aspect of the management and prevention of complication related to hypertension. Techane Sisay Tuji 1 However, self-monitoring of BP among hypertensive patients on scheduled follow-up in hospitals in Ethiopia is unknown. The aim of the study was to assess knowledge and attitude 1Nursing Department, College of Medical and Health Sciences, Arsi University, of self-monitoring of BP among adult hypertensive patients. Asella, Ethiopia; 2School of Nursing and Methods: A cross-sectional survey was conducted on 400 adult hypertensive patients attend- Midwifery, College of Health Sciences, ing follow-up clinics at four public hospitals of Arsi Zone, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia The data were collected from patients from March 10, 2019 to April 8, 2019 by face-to-face interview using a pretested questionnaire and augmented by a retrospective patients’ medical records review. The data were analyzed using the SPSS version 21.0 software. Results: A total of 400 patients were enrolled into the study with the response rate of 97.6%. The median age of the participants was 49 years (range 23–90 years). -

ETHIOPIA - National Hot Spot Map 31 May 2010

ETHIOPIA - National Hot Spot Map 31 May 2010 R Legend Eritrea E Tigray R egion !ª D 450 ho uses burned do wn d ue to th e re ce nt International Boundary !ª !ª Ahferom Sudan Tahtay Erob fire incid ent in Keft a hum era woreda. I nhabitan ts Laelay Ahferom !ª Regional Boundary > Mereb Leke " !ª S are repo rted to be lef t out o f sh elter; UNI CEF !ª Adiyabo Adiyabo Gulomekeda W W W 7 Dalul E !Ò Laelay togethe r w ith the regiona l g ove rnm ent is Zonal Boundary North Western A Kafta Humera Maychew Eastern !ª sup portin g the victim s with provision o f wate r Measle Cas es Woreda Boundary Central and oth er imm ediate n eeds Measles co ntinues to b e re ported > Western Berahle with new four cases in Arada Zone 2 Lakes WBN BN Tsel emt !A !ª A! Sub-city,Ad dis Ababa ; and one Addi Arekay> W b Afa r Region N b Afdera Military Operation BeyedaB Ab Ala ! case in Ahfe rom woreda, Tig ray > > bb The re a re d isplaced pe ople from fo ur A Debark > > b o N W b B N Abergele Erebtoi B N W Southern keb eles of Mille and also five kebeles B N Janam ora Moegale Bidu Dabat Wag HiomraW B of Da llol woreda s (400 0 persons) a ff ected Hot Spot Areas AWD C ases N N N > N > B B W Sahl a B W > B N W Raya A zebo due to flo oding from Awash rive r an d ru n Since t he beg in nin g of th e year, Wegera B N No Data/No Humanitarian Concern > Ziquala Sekota B a total of 967 cases of AWD w ith East bb BN > Teru > off fro m Tigray highlands, respective ly. -

Malt Barley Value Chain in Arsi and West Arsi Highlands of Ethiopia

Academy of Social Science Journals Received 10 Dec 2020 | Accepted 15 Dec 2020 | Published Online 29 Dec 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/DOI 10.15520/assj.v5i12.2612 ASSJ 05 (12), 1779−1793 (2020) ISSN : 2456-2394 RESEARCH ARTICLE Malt Barley Value Chain in Arsi and West Arsi highlands of Ethiopia Bedada Begna1 , Mesay Yami2 1 Kulumsa Agricultural Research Abstract Center, Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR) The study was undertaken in four districts of Arsi and West Arsi zones where malt barley is highly produced. Different participatory 2Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural rural appraisal approaches were employed to conduct the study. The Research (EIAR), National findings indicated that land allotted for malt barley production has been Fishery and Aquatic Life Research increased in the study areas since 2010, scarcity was noticed due to Center (NAFALRC) constraints related to quality and existence of malt barley competing outlets. Malt barley marketing is complex and dynamic where various actors are involved in its marketing. The marketing route changes over time depending on the demands at the terminal markets. Assela Malt Factory (AMF) plays a great role in determining malt barley price while producers are price takers. Among five major malt barley marketing channels only three of them are supplying to the factory. AMF accessed to 90% of malt barley from the channel via traders and the direct supply by farmers via cooperatives was not more than 10%. The channel via cooperatives which is strategic for both producers and the factory was serving below anticipated due to the financial constraints and management skill gaps of the cooperatives. -

Measles Outbreak Investigation and Response in Jarar Zone of Ethiopian Somali Regional State, Eastern Ethiopia

International Journal of Microbiological Research 8 (3): 86-91, 2017 ISSN 2079-2093 © IDOSI Publications, 2017 DOI: 10.5829/idosi.ijmr.2017.86.91 Measles Outbreak Investigation and Response in Jarar Zone of Ethiopian Somali Regional State, Eastern Ethiopia 12Yusuf Mohammed and Ayalew Niguse 1Ethiopian Somali Regional Health Bureau, Jigjiga, P.O. Box: 238, Jigjiga, Ethiopia 2Department of Microbiology and Public Health, Jigjiga University, P.O. Box: 1020, Jigjiga, Ethiopia Abstract: Suspected measles outbreak was notified from Degahbour hospital to the Emergency Management Team at the Regional Health Bureau. A team of experts was dispatched to the site with the objectives of confirming the existence of the outbreak, initiate measures and formulate recommendations based on the results of present outbreak investigation. We conducted descriptive cross sectional study from February to March 2016. We reviewed medical records of suspected cases; we interviewed the Health care workers, visited affected household and interviewed parents and guardians of cases. We used line list for describing measles cases interms of time, place and person. We collected five blood samples from patients for Lab confirmation. We entered and analyzed using Epi-Info7 version 7.1.0.6. During the investigation period, 406 measles cases with 5 deaths were reported with overall Attack Rate (AR) and Case Fatality Rate (CFR) was (28.2/10, 000 population, 1.2%) respectively. High AR (28.6/10000population) was reported from male. The CFR difference was not statistically significant (P value=0.66) by sex. High AR (127/10000population) was reported from age group < 1 years. When we compared AR by those < 5 years and >5 years, there was statistically significant difference (P-value= 0.00). -

Full Report (Pdf)

Working Together The sharing of water and sanitation support services for small towns and villages A WELL study produced under Task 510 by Brian Reed WELL Water and Environmental Health at London and Loughborough Water, Engineering and Development Centre Loughborough University Leicestershire LE11 3TU UK [email protected] www.lboro.ac.uk/WELL © LSHTM/WEDC, 2001 Reed, B.J. (2001) Working Together -the sharing of water and sanitation support services for small towns and villages WELL. Contents amendment record This report has been issued and amended as follows: Revision Description Date Signed 1 Draft final July 01 APC 2 Final 01/10/01 APC Designed and produced at WEDC Task Management by Andrew Cotton Quality Assurance by Andrew Cotton Cover photograph: Brian Reed (W/r Dirbe Ebrahem, village water committee member and w/r Likehesh Mengesha, tap attendant, Tereta, Ethiopia) WELL TASK 510 Working Together: draft final report Table of contents Table of contents...........................................................................................................................i List of tables................................................................................................................................ ii List of figures .............................................................................................................................. ii Acknowledgements.....................................................................................................................iii Summary .......................................................................................................................................1