Water Based Ecosystems Services and Poverty Linkages Within The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Sector Development Program

2011-12 Public Sector Development Program Planning and Development Department Government of Balochistan Government of Balochistan Planning & Development Department Public Sector Development Programme 2011-12 (Original) June, 2011 PREFACE The PSDP 2010 – 11 has seen its completion in a satisfactory manner. Out of 961 schemes, 405 schemes have successfully been completed at an aggregated expenditure of Rs. Rs.10.180 billion. Resultantly, communications links will get more strengthened in addition to increase in the employment rate in the province. More specifically, 60 schemes of water sector will definitely reinforce other sectors attached to it such as livestock and forestry. The PSDP 2011-12 has a total outlay of Rs.31.35 billion having 1084 schemes. Of this Rs.31.35 billion, 47.4% has been allocated to 590 ongoing schemes. The strategy adopted in preparation of the PSDP 2011-12 focuses chiefly on infrastructural sectors. Education, health and potable safe drinking water have been paid due attention with a view to bring about positive increase in their representation in social indicators. Worth mentioning is the fact that involvement of the Elected Members of the Provincial Assembly has excessively been helpful in identification of schemes in the constituencies having followed a well thought criteria. This has ensured that no sector has remained dormant as far its development and allocation of funds is concerned. Feasibility studies will be undertaken during FY 2011-12, especially for construction of mega dams to utilize 6.00 MAF flood water, which goes unutilized each year. Besides, feasibility studies for exploration and exploitation of viable minerals in the province will also be carried out. -

Pishin Inital Pages(F)

The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Published by: IUCN Pakistan Copyright: © 2011 IUCN, the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. Pishin - Integrated District Development Vision was developed by the Pishin District Government, with technical assistance of IUCN Pakistan under its project Balochistan Partnerships for Sustainable Development (BPSD) and financial support by the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands (EKN). Citation is encouraged. Reproduction and/or translation of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior written permission from IUCN Pakistan, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from IUCN Pakistan. The opinions expressed in this document do not constitute an endorsement by the EKN. Citation: Pishin District Government (2011). Pishin - Integrated District Development Vision. IUCN Pakistan, Quetta, Pakistan. xii+100 pp. Research and development: Abdul Latif Rao Resource person: Hamid Sarfraz Facilitation: Zabardast Khan Bangash, Mehboob Ali, Naseebullah Khan Editors: Madiha Aijaz, Zeevar Scheik and Sara Fatima Azfar Design: Azhar Saeed, IUCN Pakistan Cover photographs: Naseebullah Khan, Madiha Aijaz and IUCN Balochistan Programme Printed by: Rosette Printers Available from: IUCN Pakistan Balochistan Programme Office Marker Cottage, Zarghoon Road Quetta, Pakistan Tel: +92 (81) 2840450/51/52 Fax: +92 (81) 2820706 www.iucn.org/pakistan Pishin Integrated Development Vision Contents Acronyms . -

Barriers in Adopting Sustainable Agricultural Practices (Saps) Under Changing Climate in Balochistan, Pakistan

Pakistan Journal of Applied Social Sciences Vol. 12(1), 2021, pp.1-16, ISSN: 2409-0077(Print), ISSN: 2663-8894(Online) Barriers In Adopting Sustainable Agricultural Practices (SAPs) Under Changing Climate In Balochistan, Pakistan Ghulam Murtaza Department of Disaster Management and Development Studies University of Balochistan Siraj Bashir Department of Social Work University of Balochistan Abdul Khaliq Department of Disaster Management and Development Studies University of Balochistan Abstract Climate change is vital issue hindering sustainable agriculture development and adjustments in farming practices. Conventional agriculture practices often lead to environmental degradation, ground water depletion, financial issues and even social conflicts. The population of the globe is experiencing increased temperatures, low rainfall patterns with scarcity of water availability and drought persistence due to climate change. This article, thus, focuses on the challenges of adoption of sustainable agriculture practices (SAPs) in water scarce, drought prone province of Pakistan. Data was collected from 164 farmers by semi-structured questionnaire following multistage clustering sampling and empirically analyzed through Binary Logistic Regression Model. The results of the study elucidated that farmers’ education, their risk-taking behaviour, participation in training, limited availability and high cost of agriculture land, inherited system of irrigation, and access to agricultural credit as main barriers in adopting SAPs. The study recommends expansion of knowledge, planning, financial assistants from related institutes, proper training by the agriculture department and policy intervention to cope with these barriers that hold back the adoption of SAPs. The Government need to develop sustainable adaptive strategies for minimizing the adverse impacts of climate change on agriculture by on-farm demonstrations in the field thereby saving depleting water resources and encourage farmers to adopt sustainable agricultural practices. -

Balochistan Review” ISSN: 1810-2174 Publication Of: Balochistan Study Centre, University of Balochistan, Quetta-Pakistan

- I - ISSN: 1810-2174 Balochistan Review Volume XXXIII No. 2, 2015 Recognized by Higher Education Commission of Pakistan Editor: Ghulam Farooq Baloch BALOCHISTAN STUDY CENTRE UNIVERSITY OF BALOCHISTAN, QUETTA-PAKISTAN - II - Bi-Annual Research Journal “Balochistan Review” ISSN: 1810-2174 Publication of: Balochistan Study Centre, University of Balochistan, Quetta-Pakistan. @ Balochistan Study Centre 2015-2 Subscription rate in Pakistan: Institutions: Rs. 300/- Individuals: Rs. 200/- For the other countries: Institutions: US$ 15 Individuals: US$ 12 For further information please Contact: Ghulam Farooq Baloch Assistant Professor & Editor: Balochistan Review Balochistan Study Centre, University of Balochistan, Quetta-Pakistan. Tel: (92) (081) 9211255 Facsimile: (92) (081) 9211255 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.uob.edu.pk/journals/bsc.htm No responsibility for the views expressed by authors and reviewers in Balochistan Review is assumed by the Editor, Assistant Editor and the Publisher. - III - Editorial Board Patron in Chief: Prof. Dr. Javeid Iqbal Vice Chancellor, University of Balochistan, Quetta-Pakistan. Patron Prof. Dr. Abdul Hameed Shahwani Director, Balochistan Study Centre, UoB, Quetta-Pakistan. Editor Ghulam Farooq Baloch Asstt Professor, Balochistan Study Centre, UoB, Quetta-Pakistan. Assistant Editor Waheed Razzaq Research Officer, Balochistan Study Centre, UoB, Quetta-Pakistan. Members: Prof. Dr. Andriano V. Rossi Vice Chancellor & Head Dept of Asian Studies, Institute of Oriental Studies, Naples, Italy. Prof. Dr. Saad Abudeyha Chairman, Dept. of Political Science, University of Jordon, Amman, Jordon. Prof. Dr. Bertrand Bellon Professor of Int’l, Industrial Organization & Technology Policy, University de Paris Sud, France. Dr. Carina Jahani Inst. of Iranian & African Studies, Uppsala University, Sweden. Prof. Dr. Muhammad Ashraf Khan Director, Taxila Institute of Asian Civilizations, Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad, Pakistan. -

Pakistan Humanitarian

Pakistan Humanitarian Situation Report /Pakistan/Asad Zaidi F E C I UN © SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights January – August 2019 • In southern Pakistan, an estimated 5 million people are affected by drought in 26 districts of Sindh and Balochistan provinces due to rise in temperatures, 7,900,000 adverse effects of El Niño, and decrease in rainfall during the monsoon season. people including 4.1 million children affected by drought and TDP returnees in • In the drought affected areas, 69,424 children (6-59 months old), of whom 49% Pakistan are girls, were screened for severe acute malnutrition (SAM). 4,358 children (Pakistan HAC 2019) have been enrolled in the outpatient therapeutic programme and 28,658 children (52% girls) have been provided with multi-micronutrient supplements. 16,780 • 159,569 people were reached through health education messages and 46,304 families remain displaced in Khyber children were immunized against measles. Iron and folic acid supplementation Pakhtunkhwa merged districts was also provided to 15,429 pregnant and lactating mothers (PLWs) in the (Pakistan Humanitarian Dashboard-Transition, drought affected areas of Sindh and Balochistan. OCHA, 30 June 2019) • Newly merged districts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province saw a continuing return of temporarily displaced persons but programme achievements have 1,024 been constrained due to lack of humanitarian funding. Development funds were individuals including 824 children tested therefore leveraged to achieve results. 71,863 people were reached with Health and WASH awareness messages and 4,171 children were provided with SAM positive for HIV and AIDS in Sindh treatment while 38,088 children received micronutrient supplements. -

Balochistan Province Report on Mouza Census 2008

TABLE 1 NUMBER OF KANUNGO CIRCLES,PATWAR CIRCLES AND MOUZAS WITH STATUS NUMBER OF NUMBER OF MOUZAS KANUNGO CIRCLES/ PATWAR ADMINISTRATIVE UNIT PARTLY UN- SUPER- CIRCLES/ TOTAL RURAL URBAN FOREST URBAN POPULATED VISORY TAPAS TAPAS 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 BALOCHISTAN 179 381 7480 6338 127 90 30 895 QUETTA DISTRICT 5 12 65 38 15 10 1 1 QUETTA CITY TEHSIL 2 6 23 7 9 7 - - QUETTA SADDAR TEHSIL 2 5 38 27 6 3 1 1 PANJPAI TEHSIL 1 1 4 4 - - - - PISHIN DISTRICT 6 17 392 340 10 3 8 31 PISHIN TEHSIL 3 6 47 39 2 1 - 5 KAREZAT TEHSIL 1 3 39 37 - 1 - 1 HURAM ZAI TEHSIL 1 4 16 15 - 1 - - BARSHORE TEHSIL 1 4 290 249 8 - 8 25 KILLA ABDULLAH DISTRICT 4 10 102 95 2 2 - 3 GULISTAN TEHSIL 1 2 10 8 - - - 2 KILLA ABDULLAH TEHSIL 1 3 13 12 1 - - - CHAMAN TEHSIL 1 2 31 28 1 2 - - DOBANDI SUB-TEHSIL 1 3 48 47 - - - 1 NUSHKI DISTRICT 2 3 45 31 1 5 - 8 NUSHKI TEHSIL 1 2 26 20 1 5 - - DAK SUB-TEHSIL 1 1 19 11 - - - 8 CHAGAI DISTRICT 4 6 48 41 1 4 - 2 DALBANDIN TEHSIL 1 3 30 25 1 3 - 1 NOKUNDI TEHSIL 1 1 6 5 - - - 1 TAFTAN TEHSIL 1 1 2 1 - 1 - - CHAGAI SUB-TEHSIL 1 1 10 10 - - - - SIBI DISTRICT 6 15 161 124 7 1 6 23 SIBI TEHSIL 2 5 35 31 1 - - 3 KUTMANDAI SUB-TEHSIL 1 2 8 8 - - - - SANGAN SUB-TEHSIL 1 2 3 3 - - - - LEHRI TEHSIL 2 6 115 82 6 1 6 20 HARNAI DISTRICT 3 5 95 81 3 3 - 8 HARNAI TEHSIL 1 3 64 55 1 1 - 7 SHARIGH TEHSIL 1 1 16 12 2 1 - 1 KHOAST SUB-TEHSIL 1 1 15 14 - 1 - - KOHLU DISTRICT 6 18 198 195 3 - - - KOHLU TEHSIL 1 2 37 35 2 - - - MEWAND TEHSIL 1 5 38 37 1 - - - KAHAN TEHSIL 4 11 123 123 - - - - DERA BUGTI DISTRICT 9 17 224 215 4 1 - 4 DERA BUGTI TEHSIL 1 -

World Bank Document

The World Bank Report No: ISR9749 Implementation Status & Results Pakistan Balochistan Small Scale Irrigation Project (P089378) Operation Name: Balochistan Small Scale Irrigation Project (P089378) Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 11 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: 17-May-2013 Country: Pakistan Approval FY: 2008 Public Disclosure Authorized Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: SOUTH ASIA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): Key Dates Board Approval Date 26-Feb-2008 Original Closing Date 30-Jun-2013 Planned Mid Term Review Date Last Archived ISR Date 12-Dec-2012 Public Disclosure Copy Effectiveness Date 12-Sep-2008 Revised Closing Date 30-Jun-2013 Actual Mid Term Review Date 10-Apr-2011 Project Development Objectives Project Development Objective (from Project Appraisal Document) The development objective of the Balochistan Small Scale Irrigation Project (BSSIP) is to support efforts by the GoBalochistan to improve the management of scarce water resources in the Pishin Lora Basin (PLB) by reducing the overall impact of the present water crisis. Project activities are designed to recognize the importance of direct participation of water users and other stakeholders. Key indicators include (i) increased surface water availability and reduced groundwater depletion, (ii) increased water productivity through a combination of engineering, management, and agricultural measures, and (iii) expanded local capacity and participation of farmers to implement similar schemes and formulate plans for sustainable water resources -

Balochistan Province Reportlivestock Census 2006

TABLE 1. LIVESTOCK POPULATION AND DOMESTIC POULTRY BIRDS BY ADMINISTRATIVE UNIT NUMBER OF ANIMALS / POULTRY BIRDS ADMINISTRATIVE UNIT CATTLE BUFFALOES SHEEP GOATS CAMELS HORSES MULES ASSES POULTRY 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 BALOCHISTAN PROVINCE 2253581 319854 12804217 11784711 379528 59973 6256 471942 5911304 QUETTA DISTRICT 11244 25547 163799 120384 1377 297 106 3468 128331 PISHIN DISTRICT 91433 994 837233 504510 745 3343 467 21220 531751 KILLA ABDULLAH DISTRICT 53111 479 325020 115405 359 690 151 4008 291710 CHAGAI DISTRICT 6576 20 205725 299363 17543 100 83 4124 92931 SIBI DISTRICT 54709 6133 200946 208133 1866 2776 52 10473 254604 KOHLU DISTRICT 174167 1463 1306734 813575 58318 15755 2 53365 172462 DERA BUGTI DISTRICT 144860 6795 506095 775361 35573 11812 64 25135 185429 ZIARAT DISTRICT 1929 12 120054 138440 34 13 5 1029 50399 LORALAI DISTRICT 131806 4628 784961 331737 716 943 248 9150 252903 MUSA KHEL DISTRICT 197318 1650 977748 464126 17639 3588 96 21226 227770 BARKHAN DISTRICT 117286 2005 413840 155581 3930 2127 150 9507 155917 KILLA SAIFULLAH DISTRICT 69361 151 1066690 783624 21751 1359 270 21248 274313 ZHOB DISTRICT 178658 5524 1174735 875922 1010 370 168 18351 229782 JAFARABAD DISTRICT 268721 156427 241444 283922 8252 2929 2518 52713 507275 NASEERABAD DISTRICT 165765 84226 148501 213294 1871 1576 233 22848 292209 BOLAN DISTRICT 151736 4151 124569 766109 34401 4915 149 36325 352580 JHAL MAGSI DISTRICT 78294 4275 61295 298687 3898 3613 - 13703 157762 LASBELLA DISTRICT 101084 7980 367262 794296 32202 1857 581 26535 226710 MASTUNG DISTRICT 8628 456 466894 334906 2802 85 121 6770 218682 KALAT DISTRICT 31896 592 1239499 807608 10264 511 143 22370 331981 KHUZDAR DISTRICT 103375 5782 1105410 1036004 28006 832 185 46523 336416 AWARAN DISTRICT 18485 40 125772 344318 5335 59 20 6491 111486 KHARAN DISTRICT 14854 118 665903 635731 76069 138 8 11862 202230 KECH (TURBAT) DISTRICT 43433 306 64693 455391 6061 178 410 11060 208746 GAWADAR DISTRICT 12344 51 18363 88901 1432 12 18 4052 52893 PANJGUR DISTRICT 22508 49 91032 139383 8074 95 8 8386 64032 TABLE 2. -

TAKATOO Issue 4Volume 2 2 July – December 2010

TAKATOO Issue 4Volume 2 2 July – December 2010 Bilingual / Bi-Annual Pashto English Research Journal TAKATOO Chief Editor: Dr. Nasrullah Wazir Editor: Dr. Naseebullah Seemab Co- Editors; Faizullah Panaizi Javed Iqbal Iqbal Qari Abdul Rehman Barkat Shah Kakar Department of Pashto University of Balochistan, Quetta. E-mail: [email protected] TAKATOO Issue 4Volume 2 3 July – December 2010 Editorial Board 1. Abdul Karim Baryalai, Retired, Govt Civil Servant. 2. Prof. Dr. Salama Shaheen (Ph.D) Director Pashto Academy Department of Pashto University of Peshawar. 3. Prof. Dr. Mohmmad Islam Gohar (Ph.D) Chairman Department of Pashto University of Peshawar. 4. Prof. Dr. Parvez Mehjoor, Associate Prof. Department of Pashto University of Peshawar. 5. Dawood Azami, Program Manager, BBC UK, London. 6. Dr. Naseebullah Seemab, (Ph.D) Assistant Prof. Department of Pashto, University of Balochistan, Quetta. 7. Prof. Raz Muhammad Raz, Principle Govt Degree College, Pishin. 8. Abdul Ghafoor Lewal, President Regional Study Centre Afghanistan. 9. Ali Kumail Qazalbash, (Ph.D) Assistant Department of Persian University of Balochistan, Quetta. 10. Dr. Khushal Roohi, Germany. Composer Pashto: Hafiz Rehmatullah Niazi Composer English: Murtaza Khan Bazai Journal: Pashto Publication: Bi-Annual Serial No: IV Publisher: Department of Pashto University of Balochistan, Quetta. Press: United Printers Quetta. ________________________________________________ Department of Pashto University of Balochistan, Quetta. E-mail: [email protected] TAKATOO Issue 4Volume 2 4 July – December 2010 The Bi-annual and Bi-Lingual Research Journal TAKATOO is an academic and research endeavor of the Pashto Department which caters standardized contents with internally recognized approach and diction. Higher Education Commission of Pakistan is intended to financially support the research journal and approve it as one of the authentic source of knowledge construction and dissemination. -

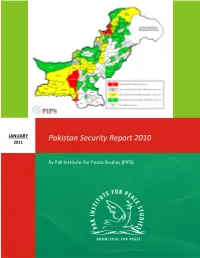

Pakistan Security Report 2010

January 201 1 Pakistan Security Report 2010 JANUARY Pakistan Security Report 20 10 201 1 By Pak Institute For Peace Studies (PIPS) 0 | P a g e January 201 1 Pakistan Security Report 2010 Contents c. Recruitment of Additional Troops in FC and Levy Force 1. Introduction 10.2 Balochistan 2. Overview 10.2.1 IDPs of Balochistan 2.1 Comparison 10.3 Ethno-Political Violence 3. Security Landscape in 2010 10.4 Counter Terrorism Initiatives 3.1 Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and FATA 10.4.1 Terrorist Arrests 3.1.1 Prominent Killings 10.4.2 Search Operations 10.4.3 Initiatives to Enhance Capacity of 3.1.2 Assassinations of Political Leaders Law Enforcement Agencies and Workers 3.1.3 Attacks on Pro-government Peace 11. Challenges and Opportunities Committees 11.1 Critical Areas 3.1.4 Abduction for Ransom 11.1.1 FATA 3.2 Balochistan 11.1.2 KPK 3.2.1Target Killings 11.1.3 Balochistan 3.2.2 Attacks/ Target Killings of 11.1.4 Karachi Political Leaders and Activists 11.1.5 South Punjab 3.2.3 Target Killings of Settlers 11.2 Critical Internal Threats 3.2.4 Enforced Disappearances 3.3 Sindh 11.2.1 Sectarian Violence 3.3.1 Karachi 11.2.2 Militant Networks and Nexus 3.3.2 Ethno-Political Violence 11.2.3 Changing Tactics and Targets by 3.4 Punjab Terrorists 3.5 Azad Kashmir 11.2.4 Growing Radicalization 3.6 Gilgit-Baltistan 11.2.5 Nexus between Terrorists and 3.7 Islamabad Criminals 4. Suicide Attacks 11.2.6. -

Development Profile District Quetta

District Development Q Development u e P R O F I L E t t 2 0 1 1 a - D i s t Quetta r i c t D e v e l o p m e n t P r o f i l e 2 0 1 1 Planning & Development Department United Nations Children’s Fund Government of Balochistan, Quetta Provincial Office Balochistan, Quetta Planning & Development Department, Government of Balochistan in Collaboration with UNICEF District Development P R O F I L E 2 0 1 1 Q u e t t a Prepared by Planning & Development Department, Government of Balochistan, Quetta in Collaboration with United Nations Children’s Fund Provincial Office Balochistan, Quetta July 18, 2011 Message Foreword In this age of knowledge economy, reliance on every possible tool The Balochistan District Development Profile 2010 is a landmark exercise of Planning and available for decision making is crucial for improving public resource Development Department, Government of Balochistan, to update the district profile data management, brining parity in resource distribution and maximizing that was first compiled in 1998. The profiles have been updated to provide a concise impact of development interventions. These District Development landmark intended for development planning, monitoring and management purposes. Profiles are vivid views of Balochistan in key development areas. The These districts profiles would be serving as a tool for experts, development practitioners Planning and Development Department, Government of Balochistan and decision-makers/specialists by giving them vast information wrapping more than 18 is highly thankful to UNICEF Balochistan for the technical and dimensions from Balochistan’s advancement extent. -

Tribunal President Abdur Rahman, Youmay Now Present Any Evidence You Haveto the Tribunal and You Havetheassistanceof Yourpersonalrepresentativeindoing So

UNCLASSIFIED SummarizedDetainee Statement Tribunal President Abdur Rahman, youmay now present any evidence you haveto the Tribunal and you havetheassistanceof yourPersonalRepresentativeindoing so . Do you wish to presentcvidence to the Tribunal? Detainee: Yes, I do. I want the assistance of my Representative. I will also say something. Tribunal President All right. Will this statement be written or oral? Detainee : I can make an oral statement . Personal Representative: The Detainee would like for me to read a written statement. will present it to the Tribunal Then the Detainee will make an oral presentation and answer questions afterwards. Tribunal President: Would you like to make your statement under a Muslim oath ? Detainee: Yes. TribunalPresident: Recorderwillyou administer the The Detaiacewas usingthe Muslimoath. In the followingsection ofthe summarizedtranscript, the PersonalRepresentative readsthe detainee's written statement attached as Exhibit - B ) to the Tribunal. statementaddresseseach pointon the UnclassifiedSummary of Evidencein order. Becausethe statementdoes notalways indicatethe text ofthe point being addressed, the pointsfromthe UnclassifiedSummaryofEvidenceare provided below in italicsto putthe detainee'sstatement intocontext. Any commentsmadeby the detainee or others whilethePersonalRepresentativereadsthe statement are summarized, as well. Tribunal President: Personal Representative, wouldyou present the information. Personal Representative: Abdur Rahmandictatedthe following written on 13 September in response to