The Empirical Status of Empirically Supported Psychotherapies: Assumptions, Findings, and Reporting in Controlled Clinical Trials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 2020 B-M-S

COMMENCEMENT THIS IS NOT AN OFFICIAL GRADUATION LIST While every effort is made to ensure accuracy in this commencement program, printing deadlines may result in omission of some names and use of names of persons not completing graduation requirements as intended. This printed program, therefore, should not be used to determine a student’s academic or degree status. The university’s official registry for conferral of degrees is the student’s permanent academic record as reflected on the student’s transcript, maintained by the Office of the University Registrar. Commencement SPRING 2020 Greetings from the President n behalf of the University of Florida, our faculty and our entire university community, I would like to extend my deepest congratulations to you, the Graduates of 2020. OI celebrate your remarkable accomplishment in earning a degree from one of the world’s leading research institutions. I applaud you for the education you have received, for honing your creative, scientific, or analytical skills and for your achievements as students. I join you in thanking your professors, advisors and family and friends for their contributions to your success. This is a time for celebration, but also for reflection on your future. I am confident that the knowledge and experience you gained as a UF student will serve you well regardless of your career or how you choose to invest your life. The university has benefited from your active engagement and contributions to your classes, programs of study and your peers, and we are grateful for your time here. We hope you will recall these years fondly, and that you will remain connected to UF as active members of our distinguished alumni. -

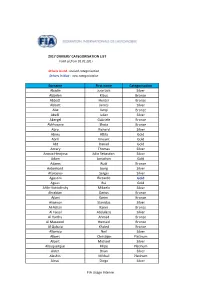

Surname First Name Categorisation Abadin Jose Luis Silver Abbelen

2018 DRIVERS' CATEGORISATION LIST Updated on 09/07/2018 Drivers in red : revised categorisation Drivers in blue : new categorisation Surname First name Categorisation Abadin Jose Luis Silver Abbelen Klaus Bronze Abbott Hunter Silver Abbott James Silver Abe Kenji Bronze Abelli Julien Silver Abergel Gabriele Bronze Abkhazava Shota Bronze Abra Richard Silver Abreu Attila Gold Abril Vincent Gold Abt Christian Silver Abt Daniel Gold Accary Thomas Silver Acosta Hinojosa Julio Sebastian Silver Adam Jonathan Platinum Adams Rudi Bronze Adorf Dirk Silver Aeberhard Juerg Silver Afanasiev Sergei Silver Agostini Riccardo Gold Aguas Rui Gold Ahlin-Kottulinsky Mikaela Silver Ahrabian Darius Bronze Ajlani Karim Bronze Akata Emin Bronze Aksenov Stanislas Silver Al Faisal Abdulaziz Silver Al Harthy Ahmad Silver Al Masaood Humaid Bronze Al Qubaisi Khaled Bronze Al-Azhari Karim Bronze Alberico Neil Silver Albers Christijan Platinum Albert Michael Silver Albuquerque Filipe Platinum Alder Brian Silver Aleshin Mikhail Platinum Alesi Giuliano Silver Alessi Diego Silver Alexander Iradj Silver Alfaisal Saud Bronze Alguersuari Jaime Platinum Allegretta Vincent Silver Alleman Cyndie Silver Allemann Daniel Bronze Allen James Silver Allgàuer Egon Bronze Allison Austin Bronze Allmendinger AJ Gold Allos Manhal Bronze Almehairi Saeed Silver Almond Michael Silver Almudhaf Khaled Bronze Alon Robert Silver Alonso Fernando Platinum Altenburg Jeff Bronze Altevogt Peter Bronze Al-Thani Abdulrahman Silver Altoè Giacomo Silver Aluko Kolawole Bronze Alvarez Juan Cruz Silver Alzen -

Geting Tau Pathology Or Other Patients with CBS Have Been Studied

VI Sindem MEETING Italian Association for the Study of Dementia linked to the Italian Neurological Society (SIN) Milan, Centro Congressi della Provincia di Milano – Via Corridoni, 16 March 17–19, 2011 PROCEEDINGS Scientifi c Committee Vincenzo Bonavita Carlo Caltagirone Claudio Mariani Alessandro Padovani Elio Scarpini Sandro Sorbi SINdem INVITED SPEAKERS The Progressive Aphasias S5 Stefano F. Cappa Corticobasal Degeneration and Corticobasal Syndrome: Lumping Versus Splitting Barbara Borroni S7 Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Dementia: The Borders Lucio Tremolizzo, Emanuela Susani, Matteo De Rosa, Michela Strozzi, Laura Marzorati, Ildebrando Appollonio and Carlo Ferrarese S10 Diagnostic Flow Chart for the Atypical Variants of Dementia Paolo Caffarra, Simona Gardini and Letizia Concari S13 Predictors of Successful Ageing: Epidemiological Evidence Laura Fratiglioni S16 Lifestyle and Rate of Progression of Cognitive Decline: Results of the SINDEM Cohort Study Massimo Musicco S17 Vascular Risk Factors and Leukoaraiosis: Results from the LADIS Study Domenico Inzitari S19 Dual Tasking and Memory Binding in Alzheimer’s Disease Sergio Della Sala, Jennifer A. Foley, Mario A. Parra and Robert H. Logie S22 Cognitive Neuroscience of Decision Making: Clinical and Implications Stefano F. Cappa S25 The Role of Emotions in Decisional Processes: How Neuroscience can Impact Evaluation of Patients’ Ability to will and to Act Paolo Nichelli, Mariangela Molinari and Francesca Benuzzi S27 Assessment of Capacity Andrea Stracciari S28 Using Biology to Untie -

Collèges Colleges

Disclosure for 2012 under the Public Sector Salary Disclosure Act, 1996 Colleges This category includes Ontario Colleges. Divulgation pour 2012 en vertu de la Loi de 1996 sur la divulgation des traitements dans le secteur public Collèges Cette catégorie contient les collèges de l’Ontario. Taxable Surname/Nom de Given Name/ Salary Paid/ Benefits/ Employer/Employeur famille Prénom Position/Poste Traitement Avant. impos. Algonquin College ABBAS SADIQ Professor $102,185.98 $119.88 Algonquin College AGATE JEFFERY MICHAEL Manager, Counselling and Testing Services$104,656.60 $335.15 Algonquin College AL-AZZAWI ABDUL Professor $103,133.47 $185.88 Algonquin College ALLAN GAIL Professor $104,893.10 $185.88 Algonquin College ALLEN IAN D. Professor $104,140.79 $119.88 Algonquin College ALMUHTADI WAHAB Professor $104,893.10 $185.88 Algonquin College ANDERSON DANIEL Professor $102,185.98 $119.88 Algonquin College ANDERSON MICHAEL Professor $104,573.33 $185.88 Algonquin College ASSELIN JACQUELINE Professor $103,539.54 $185.88 Algonquin College AUBIN JERRY A. Professor $108,961.50 $119.88 Algonquin College AUBUT JOANN Dean, Academic Development $139,301.88 $445.83 Algonquin College BAIN RODNEY Professor $102,269.74 $185.88 Algonquin College BALASEVICIUS DEBRA Chair, Health and Community Studies Department$118,961.88 $389.52 Algonquin College BALLARD MICHAEL Professor $104,893.10 $185.88 Algonquin College BARKER GERRY A. Vice President, Human Resources $204,434.22 $585.94 Algonquin College BAUCOM ALFRED Professor $102,216.63 $119.88 Algonquin College BELANGER MARIA Professor $103,611.47 $119.88 Algonquin College BERRY LYNN M. Professor $108,381.94 $185.88 Algonquin College BEST DAVE Professor $100,506.36 $185.88 Algonquin College BONANG COLIN Associate Director, Safety, Security and Emergency Management$108,989.51 $352.32 Algonquin College BOND ANTHONY R. -

2017 Drivers Categorisation List Final List 081217.Xlsx

2017 DRIVERS' CATEGORISATION LIST Valid as from 01.01.2017 Drivers in red : revised categorisation Drivers in blue : new categorisation Surname First name Categorisation Abadin Jose Luis Silver Abbelen Klaus Bronze Abbott Hunter Bronze Abbott James Silver Abe Kenji Bronze Abelli Julien Silver Abergel Gabriele Bronze Abkhazava Shota Bronze Abra Richard Silver Abreu Attila Gold Abril Vincent Gold Abt Daniel Gold Accary Thomas Silver Acosta Hinojosa Julio Sebastian Silver Adam Jonathan Gold Adams Rudi Bronze Aeberhard Juerg Silver Afanasiev Sergei Silver Agostini Riccardo Gold Aguas Rui Gold Ahlin‐Kottulinsky Mikaela Silver Ahrabian Darius Bronze Ajlani Karim Bronze Aksenov Stanislas Silver Al‐Azhari Karim Bronze Al Faisal Abdulaziz Silver Al Harthy Ahmad Bronze Al Masaood Humaid Bronze Al Qubaisi Khaled Bronze Alberico Neil Silver Albers Christijan Platinum Albert Michael Silver Albuquerque Filipe Platinum Alder Brian Silver Aleshin Mikhail Platinum Alessi Diego Silver FIA Usage Interne Surname First name Categorisation Alexander Iradj Silver Alguersuari Jaime Platinum Alleman Cyndie Silver Allemann Daniel Bronze Allgàuer Egon Bronze Allmendinger AJ Gold Almond Michael Silver Almudhaf Khaled Bronze Alon Robert Silver Altenburg Jeff Bronze Altevogt Peter Bronze Al‐Thani Abdulrahman Silver Aluko Kolawole Bronze Alvarez Juan Cruz Silver Alzen Uwe Gold Amado Ulric Gold Amaduzzi Davide Bronze Amaral Miguel Bronze Amberg Zoel Gold Amici Andrea Silver Ammermüller Michael Gold Amos Eugenio Silver Amstutz Adrian Bronze Anapoli Giovanni Bronze Andersen -

L'étoile Étrange, Année 2018, Numéro 12

L’étoile étrange #12 – Semaine du 15 septembre 2018 1 Science-fiction, Fantastique, Aventure & Fantasy Interview Alexandre S. Garcia Convention Mondiale de SF Dossier Shadowhunters 2016 S1+S2+S3A Numéro 12 - gratuit Tous droitsSemaine réservés images du 15 et septembre textes 2018 2018 L’étoile étrange #12 – Semaine du 15 septembre 2018 2 Édito La Forme de la Fantasy Urbaine. Depuis le 19ème siècle, le Fantastique Gothique s’est dopé à la frénésie spirite de la Belle époque, puis aux monstres de la MGM et enfin aux grandes épopées de Haute Fantasy à la Seigneur des Anneaux, C’est Anne Rice qui ouvre le bal avec son Entretien avec un Vampire ; Joss Whedon avec Buffy contre le vampire a dopé le genre grâce aux recettes tout droit sorties des jeux de rôles des années 1980 ; puis Charlaine Harris a mené avec le cocktail à l’eau de rose épicé True Blood, d’abord en romans puis adaptés puis sur HBO par Allan Ball. Enfin Stephenie Meyer a récolté les lauriers en faisant scintiller les vampires en plein soleil et en rejouant le grand air de la frustration sexuelle sans bain de sang, transformant au passage le cercueil de Bram Stocker en lessiveuse : les monstres sont devenus (plus ou moins) gentils, ou tout du moins, ils souffrent sincèrement quand ils vous tuent. Lorsque Star Trek la série télévisée parait dans les années 1960, les (futures) romancières de Science-fiction s’exclament : « si ce n’est que ça, écrire de la Science-fiction, alors je peux en faire autant ! ». Et les fans (surtout féminines) des amours torrides entre le capitaine James T. -

Intercultural Competence in Conflict Mediation: a Mixed-Methods Approach on Training Design and Outcome Assessment

IUL School of Social Sciences Department of Social and Organizational Psychology Intercultural Competence in Conflict Mediation: A mixed-methods approach on training design and outcome assessment Nuno Vladimiro Pereira Ramos Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Psychology Specialty in Social Psychology Supervisor: Carla Marina Madureira de Matos Moleiro, Assistant Professor ISCTE - Lisbon University Institute, Lisboa, Portugal Setembro, 2016 ii IUL School of Social Sciences Department of Social and Organizational Psychology Intercultural Competence in Conflict Mediation: A mixed-methods approach on training design and outcome assessment Nuno Vladimiro Pereira Ramos Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Psychology Specialty in Social Psychology Jury: Ph.D. Isabel Correia, Associate Professor at ISCTE-IUL, Portugal Ph.D. Ana Maria Carneiro da Costa e Silva, Assistant Professor at Universidade do Minho, Portugal Ph.D. Carla Marina Madureira de Matos Moleiro, Assistant Professor at ISCTE-IUL, Portugal Ph.D. Christin-Melanie Vauclair, FCT Researcher at ISCTE-IUL, Portugal Ph.D. Pedro Fernando Silva da Cunha, Associate Professor at Universidade Fernando Pessoa, Portugal Ph.D. Tiago Guedes do Nascimento Neves, Assistant Professor at Universidade do Porto, Portugal Julho, 2016 iii iv The present work was sponsored by a Doctoral Grant (Ref. SFRH/BD/76334/2011) of the Portuguese Science and Technology Foundation v vi Agradecimentos Algum do conhecimento que adquiri está escrito nas palavras desta tese. O final de percurso que se expressa neste documento, ritual e simbólico, não revela totalidade da experiência, consciência e sentimentos vividos. A riqueza que comigo fica é inestimável. -

List of Participants - ICAO GRSS, 24 - 26 May, 2011

List of Participants - ICAO GRSS, 24 - 26 May, 2011 Last Name First Name Company Name Country Title ClientCodes AARON ROBERT BOEING United States CAPTAIN Sponsor ABDOU THIALAW DIOP Senegal Government Official ABRAMOVIC TANJA CROATIAN CIVIL Croatia Government Official AVIATION AGENCY ACAR M. CEMIL GOVERNMENT OF Turkey HEAD OF DEPARTMENT Government Official TURKEY ACOSTA JOSE DELEGATION OF BOLIVIA Bolivia ICAO Staff/Resident Delegation AND VENEZUELA ACTON-GERVAIS SUZANNE AIRPORTS COUNCIL Canada MANAGER GLOBAL Government Official INTERNATIONAL TRAINING AISUEBEOGUN RICHARD ONOSELE FEDERAL AIRPORT Nigeria Government Official AUTHORITY ALAMOUSH SALEH JORDAN CIVIL AVIATION Jordan AIRPORT SAFETY AND Government Official REGULATORY STANDAEDS D COMMISSION ALAUFI ADEL HOSSAIN SAUDI ARABIA Saudi Arabia ICAO Staff/Resident Delegation DELEGATION TO ICAO ALEGRIA VIRGILIO ICAO Canada ICAO Staff/Resident Delegation ALEXANDER ALEXANDER DGCA INDONESIA Indonesia Government Official ALFONSO VALDES IRAIDA AVIANET Cuba HEAD OFFICER Government Official AERODROMES ALIU OLUMUYIWA BENARD ICAO Nigeria REPRESENTATIVE OF ICAO Staff/Resident Delegation NIGERIA ALLEN ANTHONY ICAO Canada COS ICAO Staff/Resident Delegation ALLOTEY SIMON ICAO Canada AIR NAVIGATION ICAO Staff/Resident Delegation COMMISSIONER 25 May 2011 Page 1 of 26 Last Name First Name Company Name Country Title ClientCodes ALVEAR EDUARDO ICAO Canada ICAO Staff/Resident Delegation ANDERSSON SOEREN COPENHAGEN AIRPORTS Denmark General Participant ANDERSSON SOEREN COPENHAGEN AIRPORTS Denmark SAFETY MANAGEMENT -

Suicide Research and Prevention

SUICIDE Volume 14 RESEARCH SUICIDERESEARCH: SELECTED READINGS : SELECTED READINGS Y. W. Koo, L. Kunde, V. Ross, D. De Leo VOL. 14 Y. W. Koo, L. Kunde, V. Ross, D. De Leo Koo, L. Kunde, V. W. Y. May 2015 — October 2015 Australian Academic Press Australian Institute for Suicide Research and Prevention www.aapbooks.com SUICIDE RESEARCH: SELECTED READINGS Volume 14 May 2015 – October 2015 Y. W. Koo, L. Kunde, V. Ross, D. De Leo Australian Institute for Suicide Research and Prevention WHO Collaborating Centre for Research and Training in Suicide Prevention National Centre of Excellence in Suicide Prevention First published in 2016 Australian Academic Press 18 Victor Russell Drive, Samford QLD 4520, Australia Australia www.australianacademicpress.com.au Copyright © Australian Institute for Suicide Research and Prevention, 2015 . Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act, 1968, no part may be reproduced without prior permission from the Australian Institute for Suicide Research and Prevention. ISBN: 978 1 9221 1766 3 Book and cover design by Maria Biaggini — The Letter Tree. Contents Foreword................................................................................................vii Acknowledgments..............................................................................viii Introduction Context ..................................................................................................1 Methodology ........................................................................................2 Key articles Barker et -

Publication DILA

o Quarante-neuvième année. – N 122 A ISSN 0298-296X Samedi 27 et dimanche 28 juin 2015 BODACCBULLETIN OFFICIEL DES ANNONCES CIVILES ET COMMERCIALES ANNEXÉ AU JOURNAL OFFICIEL DE LA RÉPUBLIQUE FRANÇAISE DIRECTION DE L’INFORMATION Standard......................................... 01-40-58-75-00 LÉGALE ET ADMINISTRATIVE Annonces....................................... 01-40-58-77-56 26, rue Desaix, 75727 PARIS CEDEX 15 Accueil commercial....................... 01-40-15-70-10 www.dila.premier-ministre.gouv.fr www.bodacc.fr Télécopie........................................ 01-40-58-77-57 BODACC “A” Ventes et cessions - Créations d’établissements Procédures collectives Procédures de rétablissement personnel Avis relatifs aux successions Avis aux lecteurs Les autres catégories d’insertions sont publiées dans deux autres éditions séparées selon la répartition suivante Modifications diverses........................................ BODACC “B” Radiations ............................................................ } Avis de dépôt des comptes des sociétés ....... BODACC “C” Banque de données BODACC servie par les sociétés : Altares-D&B, EDD, Infogreffe, Questel SAS, Tessi (Defitech), Pouey International, Scores & Décisions, Les Echos, Creditsafe France, Coface Services, Cartegie, Infolegale & Marketing, France Telecom SA Kiosque Internet Entreprises, Telino, Docapost, Bureau Van Dijk EE (Bureau Van Dijk Electronic publishing), Tinubu, Data Project, Clic Formalités et Binq Media BV. Conformément à l’article 4 de l’arrêté du 17 mai 1984 relatif à la constitution et à la commercialisation d’une banque de données télématique des informations contenues dans le BODACC, le droit d’accès prévu par la loi no 78-17 du 6 janvier 1978 s’exerce auprès de la Direction de l’information légale et administrative. Le numéro : 3,90 € Avis aux lecteurs Les parutions du BODACC cesseront d’être imprimées à compter du 1er juillet 2015. -

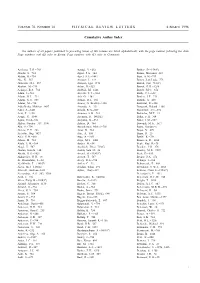

Cumulative Author Index (Print)

VOLUME 76, NUMBER 10 PHYSICALREVIEWLETTERS 4MARCH 1996 Cumulative Author Index The authors of all papers published in preceding issues of this volume are listed alphabetically with the page number following the dash. Page numbers with (E) refer to Errata. Page numbers with (C) refer to Comments. Aardema, T. G.–748 Aoyagi, Y.–232 Barkey, D.–159(E) Abachi, S.–734 Appel, J. A.– 364 Barma, Mustansir–423 Abbott, B.–734 Apsel, S. E.–1441 Baró, A. M.–799 Abe, K.–587 Aranson, I.–142 Barrat, Jean-Louis–772 Ablowitz, M. J.–857 Aranson, Igor–1170 Barratt, Carl–712(C) Abolins, M.–734 Arcon,ˇ D.–523 Barsch, G. R.– 1288 Acharya, B. S.–734 Ardebili, M.–1421 Bartelt, M. C.–652 Adam, I.–734 Arecchi, F. T. –1063 Barth, C. J.– 632 Adams, D. L.– 734 Arlt, G.–1364 Bartlett, J. F.–734 Adams, G. S.–885 Arman, M. J.–154 Bartnik, A.–415 Adams, M.– 734 Armen, G. Bradley– 1220 Bartschat, K.–208 Adda-Bedia, Mokhtar–1497 Arneodo, A.–251 Bartussek, Roland–1166 Adler, S.– 1421 Arnold, R. G.–587 Batchelder, J. C.–592 Aebi, P.–1150 Aronson, S. H.–734 Batchelor, M. T.–14 Aeppli, G.–1344 Arvanitis, D.–1403(E) Batha, S. H.–764 Agam, Oded–726 Asayama, K.–531 Bauer, J. M.–587 Ahlers, Guenter–319, 1300 Ashery, D.– 364 Bawendi, M. G.–1517 Ahn, S.– 734 Assenheimer, Michel –756 Baym, Gordon–6 Ahrens, E. T.–283 Astur, R.– 734 Bayot, V.–479 Aichelin, Jörg–1027 Atac., A.–888 Bazin, D.–26 Aifer, E. H.– 680 Ata¸c, A.–1035 Bazizi, K.–734 Aihara, H.–734 Atiya, M. -

Spring 2016 Commencement Program

COMMENCEMENT UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO BOULDER FOLSOM STADIUM MAY 7, 2016 One Hundred Fortieth Year of the University COMMENCEMENT UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO BOULDER FOLSOM STADIUM MAY 7, 2016 One Hundred Fortieth Year of the University Registrars_Commencement_May2016.indd 1 4/28/16 10:38 AM Table of Contents The Order of Exercises ..............................................................................3 The Regents of the University of Colorado ..............................................4 Norlin Charge to the Graduates ................................................................6 The Official Commencement Delegation ................................................. 7 Faculty Excellence Awards .......................................................................9 Thomas Jefferson Award ...........................................................................9 Recognition of Retired Faculty ..................................................................9 Honorary Degrees ...................................................................................10 Candidates for Doctorate Degrees ..........................................................13 Candidates for Law Degrees, School of Law .........................................18 Candidates for Graduate Degrees, Leeds School of Business ...............19 Candidates for Graduate Degrees, Graduate School . ...........................20 Undergraduate Honors ............................................................................27 College of Arts and Sciences ..................................................................31