Monitoring Xenophobic Political Discourses. a Pilot Study in Catalonia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boletín Oficial Del Estado

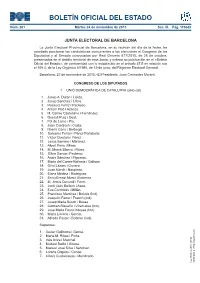

BOLETÍN OFICIAL DEL ESTADO Núm. 281 Martes 24 de noviembre de 2015 Sec. III. Pág. 110643 JUNTA ELECTORAL DE BARCELONA La Junta Electoral Provincial de Barcelona, en su reunión del día de la fecha, ha acordado proclamar las candidaturas concurrentes a las elecciones al Congreso de los Diputados y al Senado convocadas por Real Decreto 977/2015, de 26 de octubre, presentadas en el ámbito territorial de esta Junta, y ordena su publicación en el «Boletín Oficial del Estado», de conformidad con lo establecido en el artículo 47.5 en relación con el 169.4, de la Ley Orgánica 5/1985, de 19 de junio, del Régimen Electoral General. Barcelona, 23 de noviembre de 2015.–El Presidente, Joan Cremades Morant. CONGRESO DE LOS DIPUTADOS 1. UNIÓ DEMOCRÀTICA DE CATALUNYA (unio.cat) 1. Josep A. Duran i Lleida. 2. Josep Sanchez i Llibre. 3. Rosaura Ferriz i Pacheco. 4. Antoni Picó i Azanza. 5. M. Carme Castellano i Fernández. 6. Queralt Puig i Gual. 7. Pol de Lamo i Pla. 8. Joan Contijoch i Costa. 9. Noemi Cano i Berbegal. 10. Salvador Ferran i Pérez-Portabella. 11. Víctor Gonzalo i Pérez. 12. Jesús Serrano i Martínez. 13. Albert Peris i Miras. 14. M. Mercè Blanco i Ribas. 15. Sílvia Garcia i Pacheco. 16. Anaïs Sánchez i Figueras. 17. Maria del Carme Ballesta i Galiana. 18. Oriol Lázaro i Llovera. 19. Joan March i Naspleda. 20. Elena Medina i Rodríguez. 21. Enric-Ernest Munt i Gutierrez. 22. M. Jesús Cucurull i Farré. 23. Jordi Lluís Bailach i Aspa. 24. Eva Cordobés i Millán. -

«Este Es Un Daño Directo Del Independentismo»

EL MUNDO. MARTES 21 DE NOVIEMBRE DE 2017 43 ECONOMÍA i culo 155 en Cataluña es lo que ha impedido que Barcelona terminara DINERO como sede de la EMA. En un men- FRESCO saje en Twitter, calificó de «éxito del 155» que la capital catalana hubiera CARLOS sido eliminada de la carrera. Puigdemont recordó que hasta SEGOVIA el pasado 1 de octubre, fecha del referéndum ilegal, Barcelona «era España no da la favorita» para acoger este orga- nismo europeo. «Con violencia, re- una en la UE troceso democrático y el 155, el Estado la ha sentenciado», conclu- yó el ex mandatario autonómico. Los gobiernos de la UE decidieron En la misma línea se pronunció que no sólo Ámsterdam y Milán, si- el portavoz parlamentario del PDe- no incluso Copenhague –que está CAT, Carles Campuzano, quien fuera del euro– y Bratislava –cuyo afirmó que el Gobierno «no ha es- mejor aeropuerto es el de Viena– tado a la altura». eran candidatas más válidas que En un comentario publicado en Barcelona. La Ciudad Condal, que su cuenta personal de Twitter, el in- ofrecía la Torre Agbar como sede y dependentista catalán asume que el apoyo de una de las más sólidas no ganar la sede de la EMA es, «sin agencias estatales del medicamento duda, una mala noticia», si bien re- como no pasó de primera ronda, lo calca que «ni Cataluña ni Barcelo- que puede calificarse de humillación. na son quienes han fallado». A su Culpar de este fiasco totalmente al juicio, es el Gobierno quien «no ha Gobierno central como ha hecho el estado a la altura» y recuerda que ya ex presidente de la Generalitat, el Ejecutivo del PP es el principal Carles Puigdemont o parcialmente responsable ante la UE. -

The Spanish Gay and Lesbian Movement in Comparative

Instituto Juan March Centro de Estudios Avanzados en Ciencias Sociales (CEACS) Juan March Institute Center for Advanced Study in the Social Sciences (CEACS) Pursuing membership in the polity : the Spanish gay and lesbian movement in comparative perspective, 1970-1997 Author(s): Calvo, Kerman Year: 2005 Type Thesis (doctoral) University: Instituto Juan March de Estudios e Investigaciones, Centro de Estudios Avanzados en Ciencias Sociales, University of Essex, 2004. City: Madrid Number of pages: ix, 298 p. Abstract: El título de la tesis de Kerman Calvo Borobia es Pursuing membership in the polity: the Spanish gay and lesbian movement in comparative perspective, (1970–1997). Lo que el estudio aborda es por qué determinados movimientos sociales varían sus estrategias ante la participación institucional. Es decir, por qué pasan de rechazar la actuación dentro del sistema político a aceptarlo. ¿Depende ello del contexto político y de cambios sociales? ¿Depende de razones debidas al propio movimiento? La explicación principal radica en las percepciones políticas y los mapas intelectuales de los activistas, en las variaciones de estas percepciones a lo largo del tiempo según distintas experiencias de socialización. Atribuye por el contrario menor importancia a las oportunidades políticas, a factores exógenos al propio movimiento, al explicar los cambios en las estrategias de éste. La tesis analiza la evolución en el movimiento de gays y de lesbianas en España desde una perspectiva comparada, a partir de su nacimiento en los años 70 hasta final del siglo, con un importante cambio hacia una estrategia de incorporación institucional a finales de los años 80. La tesis fue dirigida por la profesora Yasemin Soysal, miembro del Consejo Científico, y fue defendida en la Universidad de Essex. -

Immigration Policy Paradoxes in Catalonia, Spain, 1985-2011: a Political Economy Approach

Immigration policy paradoxes in Catalonia, Spain, 1985-2011: a political economy approach by Luke Stobart submitted to the University of Hertfordshire in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of PhD in Business and Management Studies March 2016 Abstract Before the crisis Catalonia and the rest of Spain received high volumes of immigration – of which much was “illegal”. This was despite formally strict controls – EU policy – and different governments in Madrid claiming to operate a legal model of migration – leading to identification of a “policy paradox”. In the same period immigration became problematized, which in Catalonia allowed xenophobic politics to gain popular support – despite being a territory proactive at integrating newcomers. This research aimed to identify the undercurrents of these contradictions and respond to questions on the relative impact of business, state, national and electoral factors. It surveys literature on migration paradoxes and theories, develops an original conceptual framework by critically assessing a range of radical writing, performs quantitative and secondary study of the Catalan, Spanish and European economic and policy contexts (in general and regarding immigration), and analyses findings from interviews with privileged “insiders” and observers (employers, union leaders, migrant activists and policy advisors). Policy contradictions and the problematization of immigration were identified as rooted firstly in the inherent contradictions of the capitalist state. States must ensure availability of new reserves of labour to guarantee accumulation and make savings by not having to “socially reproduce” “imported” labour power. Yet their abstract national and bounded character propels constant nationcraft – a process best performed invisibly and negatively by symbolically and practically excluding migrants from territory, rights and citizenship. -

Julio Loras, Albert Fabà Aquellos Polvos Trajeron Estos Lodos. Diálogos Postelectorales Diciembre De 2019

Julio Loras, Albert Fabà Aquellos polvos trajeron estos lodos. Diálogos postelectorales Diciembre de 2019. La preocupación sobre el crecimiento de Vox dio lugar a un diálogo, a vuelapluma y poco sistemático, entre Julio Loras, biólogo y Alber Fabà, sociolingüista. Esas reflexiones se publicaron en Pensamiento crítico en su edición de enero. Ahora siguen dialogando, pero en este caso sobre el resultado de las últimas elecciones generales, la reacción en Catalunya a la sentencia del procés o la posibilidad de un gobierno de coalición que, en el momento en que se han redactado estas notas, aún no ha cuajado, a consecuencia de las dudas sobre la abstención (o no) de ERC en la investidura. ALBERT. Durante los últimos meses me acuerdo a menudo de Borgen, la serie de ficción en la cual tiene un notable protagonismo Kasper Juul, responsable de prensa de Birgitte Nyborg, primera ministra de Dinamarca. ¿Conoces la saga? JULIO. Hace mucho tiempo que no veo ni cine ni series. Llegaron a aburrirme. Por lo general, veía desde el principio por dónde iban a ir los tiros y perdían todo aliciente para mí. Aunque tengo algo de idea sobre esa serie por los medios. Creo que va de asesores de los políticos. ¿No es así? A. Exacto. Me viene al pelo, por eso del papel que parece que ha tenido Ivan Redondo en las decisiones que se han tomado en el PSOE, des de la moción de censura a Rajoy hasta ahora. Redondo es un típico asesor “profesional”. Que yo sepa, asesoró al candidato del PP en las municipales de Badalona en 2011. -

An Unholy Alliance

An Unholy Alliance The European Far Right and Putin’s Russia Antonis Klapsis Antonis Klapsis Antonis Credits Wilfried Martens Centre for European Studies Rue du Commerce 20 Brussels, BE 1000 The Wilfried Martens Centre for European Studies is the political foundation and think tank of the European People’s Party (EPP), dedicated to the promotion of Christian Democrat, conservative and like-minded political values. For more information please visit: www.martenscentre.eu Editor: Ingrid Habets, Research Officer, Martens Centre External editing: Communicative English bvba Layout and cover design: RARO S.L. Typesetting: Victoria Agency Printed in Belgium by Drukkerij Jo Vandenbulcke This publication receives funding from the European Parliament. © Wilfried Martens Centre for European Studies 2015 The European Parliament and the Wilfied Martens Centre for European Studies assume no responsibility for facts or opinions expressed in this publication or their subsequent use. Sole responsibility lies with the author of this publication. ISBN (to come) Table of Contents About us 04 About the author 06 Acknowledgements 08 Executive summary 10 Introduction 12 The ideological connection 16 Russia as a geopolitical alternative 24 Maintaining close contacts 32 Ukraine and Crimea 38 Exercising pressure from within 48 Conclusions 54 Policy recommendations 58 Bibliography 60 Keywords Far right – Political extremism – Russia – European Union – NATO – Anti-Americanism – Euroscepticism – Ukraine – Crimea – Populism About us Martens Centre profile The Wilfried Martens Centre for European Studies, established in 2007, is the political foundation and think tank of the European People’s Party (EPP). The Martens Centre embodies a pan-European mindset, promoting Christian Democrat, conservative and like-minded political values. -

Spain 2012 International Religious Freedom Report

SPAIN 2012 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution and other laws and policies protect religious freedom and, in practice, the government generally respected religious freedom. However, some local governments imposed restrictions that affected members of religious minority groups. For example, some Muslim and non-Catholic Christian groups stated that restrictions and policies at the local level inhibited them from assembling to practice their beliefs. The law provides taxpayers the option of allocating a percentage of their income tax to the Catholic Church but not to other religious groups. The trend in the government’s respect for religious freedom did not change significantly during the year. There were reports of societal discrimination based on religious affiliation, belief, or practice. Prominent societal leaders, however, took positive steps to promote religious freedom. Muslims continued to experience some societal prejudice and challenges related to integration. Some expressions of anti-Semitism persisted, including graffiti and the dissemination of neo-Nazi messages. U.S. officials engaged with government and religious leaders to foster dialogue and promote religious tolerance and freedom. The embassy and consulate general in Barcelona organized events with leaders of minority religious groups, and hosted speakers to share U.S. perspectives on religious freedom. Section I. Religious Demography The National Statistics Institute estimates the population to be 47 million. The government does not collect data on religious affiliation. According to a survey conducted in October by the Spanish Center for Sociological Investigation, approximately 71 percent of respondents identified themselves as Catholic and nearly 3 percent as followers of another religion. In addition, 16 percent described themselves as “non-believers,” and 9 percent as atheists. -

19 Spain. Populism from the Far Right to the Emergence of Podemos

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Mary's University Open Research Archive 19 Spain. Populism From the Far Right to the Emergence of Podemos Karen B. Sanders, Rosa Berganza, and Roberto de Miguel Introduction There is a lack of systematic research on populism and populist political communication in Spain, consisting as it does of mainly descriptive and case study work. This state of research contrasts to the greater body of work carried out in the Latin American context. The absence of a developed corpus of theoretical and empirical research leads us to argue that caution should be exercised in assessing and classifying populism and populist communication in the Spanish context at this stage. However, the evidence that we have been able to collect from published research, survey data, media accounts, and interviews with political actors allows us to present what we hope is a useful review of the state of political populism scholarship regarding Spain. Research on Populism in Spain In the May 2014 European Parliament elections, Podemos (We Can), a party registered in March 2014, won five seats and 1.2 million votes. Podemos emerged from Spain’s 2011 Outraged Movement. Although its activists and leaders claim that it is “neither of the left or of the right” (Carlin, 2015), most Spanish commentators consider it to be Spain’s most significant left-wing populist party (see, e.g., Carlin, 2015), despite the as yet limited number of publications analyzing its rise and characteristics. Until the appearance of Podemos, most research that centered on Spanish political populism relied on single case studies and treated the phenomenon as typical of the far right of Spanish politics in common with developments in other European countries (see Hernández-Carr, 2011, 2013). -

Darya Bazarkina Moscow State University for Humanities Sholokhov, Russia

Originalan naučni rad UDK 329.055.1:323.28 329.18:316.774(4-672 EU) Primljeno: 14.10.2015. Odobreno: 02.11.2015. Darya Bazarkina Moscow State University for Humanities Sholokhov, Russia RIGHT-WING EXTREMISM AND TERRORISM IN THE TERRITORY OF THE EU: FROM “STREET FIGHTERS” TO “NATIONAL-SOCIALIST UNDERGROUND” Abstract In this paper are elaborated contemporary forms of extreme right-wing in the terri- tory of the EU, with special emphasis on right-wing terrorist activities. The author paid special attention to communicational aspect of contemporary extreme right- wing actions through comparative analysis of media from the EU territories. The goal of this paper is examination of causes and consequences of the contemporary European extreme right-wing and the consequences of their actions. The ideology of neo-Nazism is explained, within which the author pointed out similarities and differences between the old and the new reforms of the right-wing extremism. The author concludes that the two main communication channels that were on-going previous years – internet and WPM scene – are still continuously used with a goal of spreading the neo-Nazi idea throughout Europe. Key words: extreme right-wing, Nazism, neo-Nazism, fascism, communication, violence, terrorism, EU. Ultra-right-wing spirits have become a big problem of the European society during the actual economic crisis. That is, for example, according to survey data which was collected by Institute for market researches in Linz, ordered by the Austri- an magazine Standard, “more than a half of the population (54%) believes that Nazis are very possible to win the elections, if it is assumed that banning of the Nauka i drustvo 2-2015.indd 85 16.12.2015 17:08:14 86 Darya Bazarkina national-socialist ideology will be overthrown”1. -

Palau De La Musica Catalana De Barcelona 36

Taula de contingut CITES 7 La Vanguardia - Catalán - 21/01/2018 "El ideal de justicia" con Javier del Pino, José Martí Gómez, José Mª Mena, José Mª Fernández Seijo y 8 Mateo Seguí que junto a Lourdes Lancho comentan la sentencia del Caso Palau que se dio a conocer .... Cadena Ser - A VIVIR QUE SON DOS DIAS - 21/01/2018 Ana Pastor, Javier Maroto, Juan Carlos Girauta, Carles Campuzano, Óscar Puente, Joan Tardá y Pablo 10 Echenique debaten sobre la corrupción política que afecta a partidos como el PP o CDC. LA SEXTA - EL OBJETIVO - 21/01/2018 Javier del Pino, Quique Peinado, Antonio Castelo y David Navarro comentan en clave de humor noticias 12 de la semana: caso Palau, trama Púnica, rama valenciana de la Gürtel, etc. Cadena Ser - A VIVIR QUE SON DOS DIAS - 20/01/2018 Entrevista a Mónica Oltra, vicepresidenta de la Generalitat Valenciana, para hablar de asuntos como los 13 recortes del gobierno, las pensiones, la corrupción en el PP y en la antigua Convergéncia o la .... LA SEXTA - LA SEXTA NOCHE - 20/01/2018 Iñaki López y los contertulios Ester Capella, Joan Mena, Maribel Martínez, Esperanza García, Lorena 16 Roldán y Carles Rivas debaten sobre la corrupción política, especialmente los casos juzgados esta .... LA SEXTA - LA SEXTA NOCHE - 20/01/2018 Iñaki López y los contertulios Ester Capella, Joan Mena, Maribel Martínez, Esperanza García, Lorena 19 Roldán y Carles Rivas debaten sobre el caso Palau de la Música y cómo afecta al PdeCAT, antigua .... LA SEXTA - LA SEXTA NOCHE - 20/01/2018 Iñaki López y el periodista Carlos Quílez analizan el caso de corrupción en Cataluña relacionado con el 21 caso Palau de la Música y cómo afecta al PdeCAT, antigua Convergència. -

Preses I Presos Bascos Al País Basc

Drets humans. Solucions. Pau. Preses i presos bascos al País Basc. Deixant enrere un conflicte que s’ha allargat massa, tant en temps com en patiment, al País Basc s’han obert noves oportunitats per construir un escenari de pau. Les converses i els acords adoptats entre diferents agents del País Basc, l’alto-el-foc d’ETA i la implicació i ajuda de la comunitat internacional, han obert el camí per solucionar el conflicte basc. Aquest ha deixat conseqüències de tot tipus i totes han de ser solucionades. Per avançar-hi, cal posar atenció també a la situació dels i les ciutadanes que a causa del conflicte estan empresonades o a l’exili, dispersats a centenars de quilometres del País Basc, amb el patiment afegit que suposa tant per a ells i elles com per als seus familiars. Com a primer pas, doncs, creiem que cal respectar els drets humans bàsics dels presos i preses basques. Respecte que comporta: · Traslladar al País Basc a tots el presos i preses bascos. · Alliberar els presos i preses amb malalties greus. · Acabar amb la prolongació de les condemnes i derogar les mesures que comporten la cadena perpètua. · Respectar tots els drets humans que els corresponen com a presos i com a persones. Per tal de reclamar als estats espanyol i francès que facin passos cap a una solució democràtica, les persones sotasignants subscrivim aquestes reivindicacions amb l’esperit d’impulsar-les des de Catalunya. I, alhora, donem suport a la mobilització del proper 12 de gener a Bilbao, convocada p e r Herrira -plataforma en defensa dels drets dels presos bascos-, amb l’adhesió d’un ampli suport social, així com de nombroses personalitats de la cultura, l’esport i la política basca. -

Seminario De Historia

SEMINARIO DE HISTORIA Dpto. de Hª Social y del Pensamiento Político, UNED Dpto. de Hª del Pensamiento y de los Movimientos Sociales y Políticos, UCM Fundación José Ortega y Gasset-Gregorio Marañón Curso 2015-2016 Documento de trabajo 2015/9 BRIDLED NATIVISM? ANTI-MUSLIM PREJUDICE IN SPANISH NORTH AFRICA AND IN CATALONIA Aitana Guía (Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, European University Institute) SESIÓN: JUEVES, 17 DE DICIEMBRE DE 2015, 19 H. Lugar: Aula 11 Instituto Universitario de Investigación Ortega y Gasset c/ Fortuny 53, 28010 Madrid Contacto: [email protected] DRAFT – PLEASE DO NOT QUOTE WITHOUT PERMISSION Bridled nativism? Anti-Muslim prejudice in Spanish North Africa and in Catalonia - AITANA GUIA - Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, European University Institute, Florence, Italy - [email protected] Introduction The worrisome rise of xenophobia in Europe in the post-Cold War period is not in doubt any longer. If for the past couple of decades analysts considered that support for the French Front National, the Austrian Freedom Party, and people’s parties in Switzerland, Denmark, or the Netherlands was a temporary phenomenon that had reached its upper limits at around 20 percent of the electoral vote, by 2014 it is clear that populism and xenophobia are growing in all European countries and have surpassed the 20 percent electoral mark in Austria, Switzerland, United Kingdom, France, Denmark, Norway, and Hungary.1 Scholars trying to make sense of the resurgence of populism and xenophobia in Europe catalog these parties and movements as extreme-right or radical right populists.2 While I think this approach yields useful results in understanding the discourse, policies, and electoral success of xenophobic parties in Europe, it does not fully explain the widespread and growing appeal of these parties to so many Europeans.