A Profile of Selected Conservatorships in Failing Mississippi School Districts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Voting Rights Act and Mississippi: 1965–2006

THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT AND MISSISSIPPI: 1965–2006 ROBERT MCDUFF* INTRODUCTION Mississippi is the poorest state in the union. Its population is 36% black, the highest of any of the fifty states.1 Resistance to the civil rights movement was as bitter and violent there as anywhere. State and local of- ficials frequently erected obstacles to prevent black people from voting, and those obstacles were a centerpiece of the evidence presented to Con- gress to support passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.2 After the Act was passed, Mississippi’s government worked hard to undermine it. In its 1966 session, the state legislature changed a number of the voting laws to limit the influence of the newly enfranchised black voters, and Mississippi officials refused to submit those changes for preclearance as required by Section 5 of the Act.3 Black citizens filed a court challenge to several of those provisions, leading to the U.S. Supreme Court’s watershed 1969 de- cision in Allen v. State Board of Elections, which held that the state could not implement the provisions, unless they were approved under Section 5.4 Dramatic changes have occurred since then. Mississippi has the high- est number of black elected officials in the country. One of its four mem- bers in the U.S. House of Representatives is black. Twenty-seven percent of the members of the state legislature are black. Many of the local gov- ernmental bodies are integrated, and 31% of the members of the county governing boards, known as boards of supervisors, are black.5 * Civil rights and voting rights lawyer in Mississippi. -

2016 NMRLS Annual Report

1966 - 2016 2016: A Commemorative Year in Review North Mississippi Rural Legal Services, Inc. A Message from the Executive Director and Board Chairman orth Mississippi Rural Legal Services, N Inc. (NMRLS) celebrated fiy years of providing legal assistance in 2016. The theme for the 50th Anniversary Celebraon was “NMRLS: The Quest for Jusce in Mississippi”. During the year, we presented special events to reflect on the Ben Thomas Cole, II, Esq. Willie J. Perkins, Sr., Esq. programs and significant ligaon which earned Executive Director Board Chairman us a renowned reputaon for aggressive legal advocacy in pursuit of remedies for the vulnerable populaon we served. Three special events were held during the year: The 50th Anniversary Kick‐Off, NMRLS Historic Ligaon Conference and the Quest for Jusce Gala. These events were designed to: Create awareness of NMRLS’ history and successes; Forge partnerships with businesses, corporaons, schools and friends; Raise funds to implement current and future programs for the commu- nies we serve; and Reconnect past and present NMRLS staff, board members, clients, aorneys and others. NMRLS achieved many successes and withstood many challenges over fiy years. The survival of our organizaon can be aributed to the vision and fortude of board members and staff who relied upon God to direct their efforts to improve the quality of life for their fellow Mississippians. Many of these heroes and others, who fought for equal jusce under the law, were recognized for their work during the Anni- versary’s special events. Some of their stories are also told in words and pictures throughout this annual report. -

2011 Annual Report

2011 ANNUAL REPORT FISCAL YEAR JULY 1, 2010 THROUGH JUNE 30, 2011 STACEY E. PICKERING STATE AUDITOR www.osa.ms.gov 2 2011 ANNUAL REPORT FISCAL YEAR JULY 1, 2010 THROUGH JUNE 30, 2011 STACEY E. PICKERING STATE AUDITOR For additional copies of the OSA Annual Report contact: Office of the State Auditor Laney Grantham Press Secretary P.O. Box 956 Jackson, Mississippi 39205 601-576-2800 Office 1-800-321-1275 Office In-State www.osa.ms.gov E-mail: [email protected] The Mississippi Office of the State Auditor does not discriminate on the basis of race, religion, national origin, sex, age or disability 3 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS PRIMARY STATUTORY RESPONSIBILITIES ..................................................................................... 6 OFFICE OF THE STATE AUDITOR’S MISSION ............................................................................. 7 AUDIT RESPONSIBILITY .............................................................................................................. 8 OFFICE CUSTOMERS ................................................................................................................... 9 DIVISIONS .................................................................................................................................. 10 OFFICE GOALS .......................................................................................................................... 11 ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICES DIVISION ........................................................................................ 13 FINANCIAL -

SOS Banner June-2014

A Special Briefing to the Mississippi Municipal League Strengthen Our Schools A Call to Fully Fund Public Education Mississippi Association of Educators 775 North State Street Jackson, MS 39202 maetoday.org Keeppublicschoolspublic.org Stay Connected to MAE! Mississippi Association of Educators "Great Public Schools for Every Student" 775 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39202 | Phone: 800.530.7998 or 601.354.4463 Websites: MAEToday.org and KeepPublicSchoolsPublic.com Ocean Springs Mayor Connie Moran Moderator Agenda 1. State funds that could be used for public education Rep. Cecil Brown (Jackson) 2. State underfunding to basic public school funding (MAEP) Sen. Derrick Simmons (Greenville) 3. Kindergarten Increases Diplomas (KIDs) Rep. Sonya Williams-Barnes (Gulfport) 4. The Value of Educators to the Community Joyce Helmick, MAE President 5. Shifting the Funding of Public Schools from the State to the Cities: The Unspoken Costs Mayor Jason Shelton (Tupelo) Mayor Chip Johnson (Hernando) Mayor Connie Moran (Ocean Springs) 8. Invest in Our Public Schools to Motivate, Educate, and Graduate Mississippi’s Students Superintendent Ronnie McGehee, Madison County School District Mississippi Association of Educators "Great Public Schools for Every Student" 775 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39202 | Phone: 800.530.7998 or 601.354.4463 Websites: MAEToday.org and KeepPublicSchoolsPublic.com Sources of State Funding That Could Be Used for Public Schools As of April 2014 $481 Million Source: House of Representatives Appropriations Chairman Herb Frierson Investing in classroom priorities builds the foundation for student learning. Mississippi Association of Educators "Great Public Schools for Every Student" 775 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39202 | Phone: 800.530.7998 or 601.354.4463 Websites: MAEToday.org and KeepPublicSchoolsPublic.com From 2009 – 2015, Mississippi’s State Leaders UNDERFUNDED* All School Districts in Mississippi by $1.5 billion! They deprived OUR students of . -

21St Century Community Learning Grants in Mississippi

21st Century Community Learning Grants in Mississippi Grantee City Contact Award Year Year One Award Program Description Project JUMP 21st Century Community Learning Center serves students at Barr Elementary School, Jim Hill High School, and Lanier High School in an after-school program and various summer activities including Camp 100 Black Men of Jackson, Inc. Jackson Maxine Lyles 2004 $242,767 100, a seven week summer camp. The Consortium’s proposal is designed to address the needs of a two-county area (Alcorn and Prentiss) served by four public school districts. The project includes after- school and summer academic and enrichment programs Alcorn County School District Corinth Jean McFarland 2004 $448,354 and activities. The Amite County Community Learning Center Program consists of the following Components: Amite County School District Liberty Mary Russ 2004 $199,254 Before- and after-school and summer recess activities. Amory's project provides after-school and summer tutoring, enrichment, and literacy/media nights at all four school sites. Additionally, services are provided at one Amory School District Amory Susan Martin 2002 $461,096 community site and several faith-based sites. THIS GRANT ALLOWS US TO OFFER AFTER SCHOOL TUTORIALS FOR LOW PERFORMING STUDENTS AND OTHER STUDENTS IF THEY NEED Benoit School District BENOIT SUZANNE HAWLEY 2004 $109,341 ADDITIONAL INSTRUCTION. To provide a math & reading skill program to maintain or enhance present skill levels. Provide a program to develop self-discipline, and self-esteem.Help members Boys and Girls Club of Central develop skills to score proficiently or above on the Miss Mississippi Jackson Bob Ward 2004 $170,000 Curriculum Test. -

Section 7. Elections

Section 7 Elections This section relates primarily to presiden- 1964. In 1971, as a result of the 26th tial, congressional, and gubernatorial Amendment, eligibility to vote in national elections. Also presented are summary elections was extended to all citizens, tables on congressional legislation; state 18 years old and over. legislatures; Black, Hispanic, and female officeholders; population of voting age; Presidential election—The Constitution voter participation; and campaign specifies how the President and Vice finances. President are selected. Each state elects, by popular vote, a group of electors equal Official statistics on federal elections, col- in number to its total of members of Con- lected by the Clerk of the House, are pub- gress. The 23d Amendment, adopted in lished biennially in Statistics of the Presi- 1961, grants the District of Columbia dential and Congressional Election and three presidential electors, a number Statistics of the Congressional Election. equal to that of the least populous state. Federal and state elections data appear also in America Votes, a biennial volume Subsequent to the election, the electors published by Congressional Quarterly, meet in their respective states to vote for Inc., Washington, DC. Federal elections President and Vice President. Usually, data also appear in the U.S. Congress, each elector votes for the candidate Congressional Directory, and in official receiving the most popular votes in his or state documents. Data on reported regis- her state. A majority vote of all electors is tration and voting for social and eco- necessary to elect the President and Vice nomic groups are obtained by the U.S. President. -

Appendix B: Maps of Mississippi's Public School Districts

Appendix B: Maps of Mississippi’s Public School Districts This appendix includes maps of each Mississippi public school district showing posted bridges that could potentially impact school bus routes, noted by circles. These include any bridges posted for single axle weight limits of up to 20,000 pounds and bridges posted for gross vehicle weight limits of up to 33,000 pounds. Included with each map is the following information for each school district: the total number of bridges in the district; the number of posted bridges potentially impacting school districts, including the number of single axle postings, number of gross weight postings, and number of tandem axle bridges; the number of open bridges that should be posted according to bridge inspection criteria but that have not been posted by the bridge owners; and, the number of closed bridges.1 PEER is also providing NBI/State Aid Road Construction bridge data for each bridge posted for single axle weight limits of up to 20,000 pounds and gross vehicle weight limits of up to 33,000 pounds. Since the 2010 census, twelve Mississippi public school districts have been consolidated with another district or districts. PEER included the maps for the original school districts in this appendix and indicated with an asterisk (*) on each map that the district has since been consolidated with another district. SOURCE: PEER analysis of school district boundaries from the U. S. Census Bureau Data (2010); bridge locations and statuses from the National Bridge Index Database (April 2015); and, bridge weight limit ratings from the MDOT Office of State Aid Road Construction and MDOT Bridge and Structure Division. -

Fiscal Year 2016 Title I Grants to Local Educational Agencies - MISSISSIPPI

Fiscal Year 2016 Title I Grants to Local Educational Agencies - MISSISSIPPI FY 2016 Title I LEA ID District Allocation* 2800360 Aberdeen School District 783,834 2800390 Alcorn School District 916,360 2800420 Amite County School District 738,597 2800450 Amory School District 569,805 2800510 Attala County School District 552,307 2800540 Baldwyn School District 364,271 2800570 Bay St. Louis School District 983,511 2800690 Benoit School District 239,518 2800600 Benton County School District 542,028 2800630 Biloxi Public School District 2,051,430 2800820 Booneville School District 347,892 2800840 Brookhaven School District 1,359,723 2800870 Calhoun County School District 922,371 2800900 Canton Public School District 1,813,829 2800930 Carroll County School District 351,882 2800960 Chickasaw County School District 161,818 2800990 Choctaw County School District 710,829 2801020 Claiborne County School District 962,449 2801050 Clarksdale Municipal School District 2,394,213 2801080 Clay County School District 219,189 2800750 Cleveland School District 1,877,888 2801090 Clinton Public School District 919,113 2801110 Coahoma County School District 1,244,888 2801140 Coffeeville School District 337,445 2801170 Columbia School District 914,516 2801200 Columbus Municipal School District 2,695,637 2801220 Copiah County School District 1,111,014 2801260 Corinth School District 947,110 2801290 Covington County School District 1,354,830 2801320 DeSoto County School District 5,152,857 2801360 Durant Public School District 434,398 2801380 East Jasper School District -

Filed!Accepted

WOMBlE Seventh Floor 1401 Eye Street, N.W CARLYlE Washington. DC 20005 SANDRIDGE Telephone: (202) 467·6900 Mark J. Palchick & RICE Fax; (202) 467-6910 Direct Dial: (202) 857-4411 Web site: WWW.WCSf.com Direct Fax: (202) 261-0011 " PROfeSSIONAL LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY E-mail: [email protected] October 23, 2006 FILED!ACCEPTED Ms. Gina Spade OCT 232006 Federal Communications Commission Federal Communications Commissioo 445 12th Street, SW Office of \fle Secretary Room 5-C330 Washington, DC 20554 Re: Follow up information: Docket Numbers CC 02-60; CC 96-45; CC 97-21; WC 03-109; and WC 05-195 Dear Ms Spade: We met with you and other members ofthe Wireless Competition Bureau on August 15, th 2006. On the 15 , we also met with Commissioner Adelstein, Scott Bergmann, Scott Deutchman, Dana Shaffer, and Michelle Carey. The purpose ofthis letter is to respond to the following requests for additional information which were made as a result ofour August 15, 2006 meetings. I. Why did the number ofservice providers in Mississippi decrease from 105 to 55 during the period 1998 to 2005. 2. What schools receive service from Synergetics. 3. Where there have been selective reviews ofSynergetics billed entities, what was the result. 4. What were the reasons that Synergetics billed entities were denied funding and the dollar value ofthe denials. 5. Where any ofSynergetics billed entities denied funding because ofpattern analysis and ifso what was the dollar value ofthe denials. 6. Does Synergetics know what could have triggered the selective reviews. 7. Summary ofSynergetics meeting with the USAC representatives. -

06. Approval of Course of Action for Bolivar County School District Consolidation As Required by Senate Bill 2760

OFFICE OF SCHOOL IMPROVEMENT, OVERSIGHT AND RECOVERY Summary of State Board of Education Agenda Items October 18-19, 2012 OFFICE OF SCHOOL IMPROVEMENT, OVERSIGHT AND RECOVERY 06. Approval of course of action for Bolivar County School District consolidation as required by Senate Bill 2760 Recommendation: Approval Back-up material attached 1 Course of Action for Bolivar County School District Consolidation 1. State Board should review comments from the October 15th meeting offered by the affected school districts and appoint a subcommittee to hear comments from each district regarding the eventual criteria that the SBE must adopt to guide the redistricting process. The subcommittee may hold a meeting with each district for the purpose of hearing comments regarding redistricting criteria. 2. SBE should review comments from the affected districts submitted by the subcommittee. 3. SBE should review comments from the community meetings at the January 18 meeting and may adopt official criteria for reapportionment and redistricting of the new consolidated school districts. 4. Draft maps will be delivered to the districts in Bolivar County as soon as they are prepared. 5. At the February 15 meeting, SBE can review all public comments or written information submitted. 6. SBE should adopt new board member districts for North Bolivar Consolidated School District, and West Bolivar Consolidated School District at the March meeting and submit the required information to the Department of Justice. 2 MISSISSIPPI LEGISLATURE REGULAR SESSION 2012 By: Senator(s) -

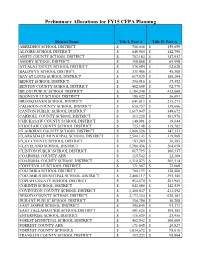

FY2015 CFPA Preliminary Allocations

Preliminary Allocations for FY15 CFPA Planning District Name Title I, Part A Title II, Part A ABERDEEN SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 706,046 $ 159,659 ALCORN SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 649,965 $ 142,790 AMITE COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 702,184 $ 147,952 AMORY SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 358,868 $ 69,998 ATTALA COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 576,084 $ 92,628 BALDWYN SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 331,486 $ 45,308 BAY ST LOUIS SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 617,525 $ 188,294 BENOIT SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 250,910 $ 37,452 BENTON COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 462,608 $ 92,779 BILOXI PUBLIC SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 1,184,246 $ 432,009 BOONEVILLE SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 180,022 $ 36,093 BROOKHAVEN SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 841,813 $ 215,273 CALHOUN COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 630,757 $ 139,606 CANTON PUBLIC SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 1,617,947 $ 349,672 CARROLL COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 313,220 $ 101,976 CHICKASAW COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 149,081 $ 19,644 CHOCTAW COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 725,148 $ 119,702 CLAIBORNE COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 1,006,526 $ 147,353 CLARKSDALE MUNICIPAL SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 2,500,143 $ 319,988 CLAY COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 183,269 $ 36,585 CLEVELAND SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 1,280,438 $ 264,059 CLINTON PUBLIC SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 617,795 $ 166,337 COAHOMA COUNTY AHS$ 115,542 $ 22,309 COAHOMA COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 1,310,073 $ 205,514 COFFEEVILLE SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 371,567 $ 72,068 COLUMBIA SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 700,193 $ 128,406 COLUMBUS MUNICIPAL SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 2,400,117 $ 395,145 COPIAH COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 914,570 $ 201,981 CORINTH SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 842,080 $ 142,539 COVINGTON COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 1,400,047 $ 211,492 DESOTO COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 3,172,354 -

SL31 Funding Year 2012 Authorizations

Universal Service Administrative Company Appendix SL31 Schools and Libraries 4Q2013 Funding Year 2012 Authorizations - 2Q2013 Page 1 of 190 Applicant Name City State Primary Authorized (Fields Elementary) SOUTH HARNEY SCHOOL FIELDS OR 675.00 100 ACADEMY OF EXCELLENCE NORTH LAS VEGAS NV 16,429.32 21ST CENTURY CHARTER SCHOOL @ GARY GARY IN 325,743.99 4-J SCHOOL GILLETTE WY 697.72 A B C UNIFIED SCHOOL DISTRICT CERRITOS CA 16,506.78 A HOLMES JOHNSON MEM LIBRARY KODIAK AK 210.00 A SPECIAL PLACE SANTA ROSA CA 4,867.80 A W BEATTIE AVTS DISTRICT ALLISON PARK PA 8,971.58 A+ ARTS ACADEMY COLUMBUS OH 3,831.75 A.W. BROWN FELLOWSHIP CHARTER SCHOOL DALLAS TX 113,773.07 AAA ACADEMY POSEN IL 8,676.99 ABERDEEN PUBLIC LIBRARY ABERDEEN ID 2,236.80 ABERDEEN SCHOOL DISTRICT ABERDEEN MS 9,261.29 ABERDEEN SCHOOL DISTRICT 5 ABERDEEN WA 53,979.45 ABERDEEN SCHOOL DISTRICT 58 ABERDEEN ID 13,497.79 ABERNATHY INDEP SCHOOL DIST ABERNATHY TX 13,958.23 ABILENE FREE PUBLIC LIBRARY ABILENE KS 624.07 ABILENE INDEP SCHOOL DISTRICT ABILENE TX 18,698.04 ABILENE UNIF SCH DISTRICT 435 ABILENE KS 5,280.10 ABINGTON COMMUNITY LIBRARY CLARKS SUMMIT PA 259.00 ABINGTON SCHOOL DISTRICT ABINGTON PA 8,348.30 ABINGTON SCHOOL DISTRICT ABINGTON MA 6,133.45 ABSAROKEE SCHOOL DIST 52-52 C ABSAROKEE MT 1,430.26 ABSECON PUBLIC LIBRARY ABSECON NJ 131.30 ABSECON PUBLIC SCHOOL DISTRICT ABSECON NJ 5,091.22 ABUNDANT LIFE CHRISTIAN ACAD MARGATE FL 860.00 ACADAMY OF ST BARTHOLOMEW MIDDLEBURG HTS.