AN ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT of CHINA's WTO ACCESSION an Analysis of Six Sectors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Olympic Fencers Ages

Name CountryName Year EventName Birth Finals date Age (days) Lamon, Sophie Switzerland 2000 Women's Epee Individual 1985-02-08 Sunday, September 17, 2000 5700 Lamon, Sophie Switzerland 2000 Women's Epee Team 1985-02-08 Tuesday, September 19, 2000 5702 Al-Awadhi, Khaled Kuwait 1980 Men's Foil Individual 1964-09-13 Wednesday, July 23, 1980 5792 Al-Awadhi, Khaled Kuwait 1980 Men's Foil Team 1964-09-13 Saturday, July 26, 1980 5795 Muller Karger, Gerda Venezuela 1952 Women's Foil Individual 1936-09-07 Sunday, July 27, 1952 5802 Israel 1976 Women's Foil Individual 1960-08-07 Saturday, July 24, 1976 5830 (נילי דרורי) Drori, Nili Álvarez Villalba, José Marcelo Paraguay 1992 Men's Foil Individual 1975-12-24 Friday, July 31, 1992 6064 Álvarez Villalba, José Marcelo Paraguay 1992 Men's Epee Individual 1975-12-24 Saturday, August 01, 1992 6065 Al-Sureayei, Saqer Kuwait 1988 Men's Foil Individual 1972-01-24 Wednesday, September 21, 1988 6085 Al-Sureayei, Saqer Kuwait 1988 Men's Foil Team 1972-01-24 Tuesday, September 27, 1988 6091 Reuche, Marguerite France 1928 Women's Foil Individual 1911-11-13 Thursday, August 02, 1928 6107 Dwinger, Max Netherlands 1960 Men's Epee Individual 1943-12-05 Tuesday, September 06, 1960 6120 Fonst Segundo, Ramón Cuba 1900 Men's Epee Individual 1883-08-31 Thursday, June 14, 1900 6131 Fonst Segundo, Ramón Cuba 1900 Master's/Amateur's Epee 1883-08-31 Friday, June 15, 1900 6132 Vaccaroni, Dorina Italy 1980 Women's Foil Individual 1963-09-24 Thursday, July 24, 1980 6148 Vaccaroni, Dorina Italy 1980 Women's Foil Team 1963-09-24 -

Youth Olympic Games: Snow! in the and 31 December 1999)

FACTSHEET THE YOG – FACTS AND FIGURES UPDATED – NOVEMBER 2018 - 4 OF 4 PAST AND FUTURE Bearers of the Olympic flag: Frank Fredericks (athletics), Patricia Chan Li-Yi (swimming), Sergey EDITIONS Bubka (athletics), Dr Tan Eng Liang, Tan Howe ST Liang (weightlifting), Tao Li (swimming), Yang Yang THE 1 SUMMER YOG – SINGAPORE 2010 (speed skating) and Yelena Isinbaeva (athletics). Election: Conducted by postal vote. Former IOC President Jacques Rogge announced the result at The Olympic Museum in Lausanne on 21 February 2008. The other Candidate Cities were: Athens (Greece), Bangkok (Thailand), Debrecen (Hungary), Guatemala City (Guatemala), Kuala Lumpur (Malaysia), Moscow (Russian Federation), Poznań (Poland), and Turin (Italy). In the final vote, Singapore was elected with 53 votes to 44 for Moscow. KEY FACTS AND FIGURES Dates: 14 to 26 August 2010 Youth athlete bearers of the Olympic flag: NOC participated: 204 + Independent Olympic Isabelle Li Siyun (table tennis), Lee Shang Hui Participants (athletes from Kuwait, owing the Carol (shooting), Natasha Michiko Yokoyama suspension of their NOC) (sailing), Rania Herlina Rahardja (fencing), Timothy Athletes: 3,524 (1,678 girls; 1,846 boys) Tay (gymnastics) and Zachary Ryan Devaraj Events: 201, in 26 sports (athletics). Volunteers: 20,000 Young Reporters: 29 Media: 1,768 Young Ambassadors: 29 Mascots: Lyo and Merly. Athlete Role Models: 47 Lyo is an abbreviation of “Lion of the Youth YOG Ambassadors: Michael Phelps (USA), Olympic Games”. The lion is the national symbol Yelena Isinbaeva (RUS) and Usain Bolt (JAM). of Singapore. Merly comes from “merlion”, a Age groups: Depending on the sports and mythical sea creature (with the body of a lion and disciplines, athletes were 15, 16, 17 or 18 on 31 head of a fish), a symbol from local folklore. -

Fencing World Championship Medallists by Country

Fencing World Championship Medallists by Country by George Masin This report shows every country’s medallists in every FIE World Championship (cadet, junior, senior, or veteran). Country Codes Code English French Spanish AFG Afghanistan Afghanistan Afganistán AHO Netherlands Antilles Antilles Neerlandaises Antillas Holandesas ALG Algeria Algerie Argelia ANT Antigua & Barbuda Antigua-et-Barbuda Antigua y Barbuda ARG Argentina Argentine Argentina ARM Armenia Armenie Armenia ARU Aruba Aruba Aruba AUS Australia Australie Australia AUT Austria Autriche Austria AZE Azerbaidjan Azerbaidjan Azerbaiyan BAH Bahamas Bahamas Bahamas BAN Bangladesh Bangladesh Bangladés BAR Barbados Barbade Barbados BEL Belgium Belgique Belgica BEN Benin Bénin Benín BER Bermuda Bermudes Bermudas BIZ Belize Belize Belice BLR Belarus Belarus Bielorrusia BOH Bohemia Bohemie Bohemia BOL Bolivia Bolivie Bolivia BOT Botswana Botswana Botsuana BRA Brazil Bresil Brasil BRN Bahrain Bahrein Barein BRU Brunei Darussalam Brunei Darussalam Brunei Darusalam BUL Bulgaria Bulgarie Bulgaria BUR Burkina Faso Burkina Faso Burkina Faso CAM Cambodia Cambodge Camboya CAN Canada Canada Canada CGO Congo Congo Congo CHI Chile Chili Chile CHN China Chine China CIV Ivory Coast Côte d'Ivoire Costa de Marfil CMR Cameroon Cameroun Camerún COD Democratic Republic of Congo Republique Democratique du Congo Republica Democratica del Congo COL Colombia Colombie Colombia CRC Costa Rica Costa Rica Costa Rica CRO Croatia Croatie Croacia C-U Cuba/USA Cuba/USA Cuba/USA CUB Cuba Cuba Cuba CYP Cyprus Chypre Chipre CZE Czech Republic Republique Tchèque Republica Checa DEN Denmark Danemark Dinamarca DMA Dominica Dominique Dominica DOM Dominican Republic Republique Dominicaine Republica Dominicana ECU Ecuador Equateur Ecuador EGY Egypt Egypte Egipto ESA El Salvador El Salvador El Salvador ESP Spain Espagne España Country Codes Code English French Spanish EST Estonia Estonie Estonia EUN Unified Team Équipe Unifiée Equipo Unificado FIN Finland Finlande Finlandia FRA France France Francia FRG Germany, West Allemagne, Ouest R.F.A. -

Vogalonga 50

Venezia VENEZIA - MANIFESTAZIONI 2011 MANIFESTAZIONI 2011 CITTÀ DI VENEZIA VeneziaMANIFESTAZIONI 2011 Calendario 2011 Redazione: Elena Bianchetto, Lucia Diglio In copertina: Foto Archivio R.S.C. Bucintoro Foto di: Fotoattualità, Francesco Dal Sacco, Chiara Florian, Archivio R.S.C. Bucintoro Inserzionisti Banco San Marco (2° copertina); Hello Kitty Mania (pag. 1); Ristorante Al Giardinetto (pag. 11); Hotel Iris (pag. 11); Terminal Fusina (pag. 24); Kappa Venezia (pag. 25); Osteria La Perla Ai Bisatei (pag. 28); Cinain (pag. 29); Consorzio Cantieristica Minore Veneziana (pag. 37); Luigi Bagarotto S.A.S (pag. 42); Dei Rossi Shipping (pag. 45); Cantiere Nautico Mardegan (pag. 47); Fotoattualità (pag. 47); Scuola Sci & Snowboard Equipe (pag. 47); Trevissoi (pag. 49); Ingemar (pag. 51); Nautica Marton (pag. 51); Hydro Mirò (pag. 51); Hosteria Bar- barigo (pag. 59); Ali Bio Alimentari & Biologico (pag. 59); New Jolly (pag. 59); Osteria “Ae Sconte” (pag. 63); Trattoria Ai Cugnai (pag. 63); Trattoria alle Vignole (pag. 63); Expovenice (pag. 67); Foltran Auto (pag. 71); Alimentari Eredi Scarpa Franco (pag. 73); Queen of Casablanca (pag. 73); Zambon (pag. 73); Pasticceria Tonolo (pag. 77); Rein (pag. 77); Gelateria e Pizzeria Mille Voglie (pag. 84); Trat- toria “da Ignazio” (pag. 87); Pavilegno di Salvador Dalvano (pag. 87); Trattoria “La rosa dei venti” (pag. 87); Editgraf (pag. 88); Com- puservice (pag. 88); B. Broker srl (terza di copertina); Consorzio Venezia Nuova (quarta di copertina). design: Compuservice, Venezia - www.compuservicevenezia.it -

Youth Olympic Games”

FACTSHEET THE YOG - FACTS AND FIGURES UPDATED – NOVEMBER 2015 -4 OF 4 Athletes: 3,524 (1,678 girls; 1,846 boys) Events: 201, in 26 sports Volunteers: 20,000 Media: 1,768 Team Officials: 1,871 Mascots: Lyo and Merly. Lyo is an abbreviation of “Lion of the Youth Olympic Games”. The lion is the national symbol of Singapore. Merly comes from “merlion”, a mythical sea creature (with the body of a lion and head of a fish), a symbol from local folklore. Official opening of the Games: Sellapan Ramanathan, President of the Republic of Singapore. Lighting of the Olympic cauldron: Darren PAST AND FUTURE Choy (SIN), sailing. EDITIONS Torch bearers: Amanda Lim Xiang Qi (swimming), Silas Abdul Razak (hockey), ST THE 1 SUMMER YOG – Griselda Khng (sailing), Jeffrey Adam Lightfoot SINGAPORE 2010 (football) and Jasmine Ser Xiang Wei (shooting). The first Summer Youth Olympic Games were Olympic oath (athletes): Caroline Rosanna held in Singapore in 2010. Chew Pei Jia (SIN), equestrian. The host city election was conducted by postal Olympic oath (officials): Syed Abdul Kadir vote. Former IOC President Jacques Rogge (SIN), boxing. announced the result at The Olympic Museum Olympic oath (coaches): David Lim Fong in Lausanne on 21 February 2008. The other Jock (SIN), head coach, aquatics. Candidate Cities were: Athens (Greece), Bearers of the Olympic flag: Frank Bangkok (Thailand), Debrecen (Hungary), Fredericks (athletics), Patricia Chan Li-Yi Guatemala City (Guatemala), Kuala Lumpur (swimming), Sergey Bubka (athletics), Dr Tan (Malaysia), Moscow (Russian Federation), Eng Liang, Tan Howe Liang (weightlifting), Poznań (Poland), Singapore (Singapore) and Tao Li (swimming), Yang Yang (speed Turin (Italy). -

World Championship Fencing Individual Results

World Championship Fencing Individual Results by George Masin This report shows the individual event medallists at every FIE World Championship (cadet, junior, senior, and veteran). Fencing World Championship Individual Medalists 1921 European Championships (Paris, FRA - 1921.VI.10-11) Prior to 1921 there were a number of competitions that called themselves World Championships. These were usually challenge matches between two fencers each or both of which called themselves world champions. Prior to the establishment of the Federation Internationale d’Escrime (FIE) in 1913, however, there was no international body to sanction a real world championship. It was not until after World War I and the 1920 Olympic Games, though, that the FIE finally sanctioned a championship. In these early championships, each country was allowed to enter a maximum of eight fencers. From 1921 through 1936 (except in the Olympic years of 1924 and 1928) the FIE sanctioned yearly competitions called the “Championnats d'Europe” (“European Championships”). In spite of their name, non-Europeans were allowed to compete in them and so these competitions are considered to be the first world championships for fencing. It was not until 1937 that the FIE officially changed the name of the competitions from “Championnats d'Europe” to “Championnats du Monde”. Men's Epee Individual (1921.VI.10-11) The European Championships were held as one of the events during the Grande Semaine des Armes de Combat which ran from June 5 to 12 and included the French national fencing championships and other fencing events as well as shooting events. Only one European Championship event was contested: men's epee individual. -

6 Olympics TUESDAY, JULY 24, 2012 CHINA DAILY TEAM CHINA BOUND for LONDON

6 olympics TUESDAY, JULY 24, 2012 CHINA DAILY TEAM CHINA BOUND FOR LONDON BOXING Chinese boxers will attempt to at least equal the two titles they won four years ago in Beijing. The women’s event will debut this summer. Zou Shiming, the 49kg champion, is Fighting chances in London expected to defend his gold medal. Zhang Zhilei is in position to win the super heavyweight category. In the women’s event, amateur world champion Ren Cancan is keen to Performances in gold-rich combat sports — boxing, judo, taekwondo and wrestling — claim the Games’ fi rst 51kg title, while Dong Cheng is punching for a medal at 60kg and Li Jinzi at 75kg. could decide how close China comes to the US in the medal count, China Daily reports. RESULTS AT PREVIOUS OLYMPICS 2004 Athens Games: 1 bronze medal (men’s 48kg) TENNIS ROSTER 2008 Beijing Games: 2 gold medals (men’s 48kg and 81kg) Women: Peng Shuai, Zheng Jie, Li Na, Zhang Shuai China Daily’s gold-medal projec- tion for London: 2 gold medals Is there a fi fth ROSTER RESULTS AT PREVIOUS OLYMPICS Men: Liu Qiang, Memeturson Jon, Meng Fanlong, Wang Xuanxuan, 2004 Athens Games: 1 gold Grand Slam now? medal (women’s doubles) Zhang Zhilei, Zou Shiming Women: Dong Cheng, Li Jinzi, 2008 Beijing Games: 1 bronze Ren Cancan Th e four Grand Slams of tennis dominate the sport’s medal (women’s doubles) STARS TO WATCH annual calendar, but every fourth year the increasingly China Daily’s gold-medal projection for London: 0 gold Zou Shiming, 31 important Olympic Games tournament rolls around. -

Arxiv:1710.02991V3 [Cond-Mat.Str-El] 4 Oct 2020 Entanglement Dances to the Stage of Real Materials

Evidences for the topological order in a kagome antiferromagnet Yuan Wei,1, 2 Zili Feng,1, 2 Wiebke Lohstroh,3 D. H. Yu,4 Duc Le,5 Clarina dela Cruz,6 Wei Yi,7 Z. F. Ding,8 J. Zhang,8 Cheng Tan,8 Lei Shu,8, 9 Yan-Cheng Wang,10 Han-Qing Wu,11 Jianlin Luo,1, 2, 12 Jia-Wei Mei,13 Fang Yang,14 Xian-Lei Sheng,14 Wei Li,14, 15 Yang Qi,16, 9 Zi Yang Meng,1, 17, 12, ∗ Youguo Shi,1, 18, 12, y and Shiliang Li1, 2, 12, z 1Beijing National Laboratory for Condensed Matter Physics, Institute of Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100190, China 2School of Physical Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100190, China 3Heinz Maier-Leibnitz Zentrum (MLZ), Technische Universita¨t Mu¨nchen, Garching D-85747, Germany 4Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organization, Lucas Heights, New South Wales 2232, Australia 5ISIS Facility, Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, Chilton, Didcot OX11 0QX, United Kingdom 6Neutron Scattering Division, Neutron Sciences Directorate, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, Tennessee 37831, USA 7International Center for Materials Nanoarchitectonics, National Institute for Materials Science, 1-1 Namiki, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-0044, Japan 8State Key Laboratory of Surface Physics, Department of Physics, Fudan University, Shanghai 200433, China 9Collaborative Innovation Center of Advanced Microstructures, Nanjing 210093, China 10School of Physical Science and Technology, China University of Mining and Technology, Xuzhou Jiangsu, 221116, People's Republic of China 11School of Physics, Sun Yat-Sen University, -

Quality of Service Specification in Video

Quality of Service Specification in Video Databases Elisa Bertino¤ Tiziana Catarciy Ahmed K. Elmagarmidz Mohand-Sa¨ıdHacidx ¤Dipartimento di Scienze dell’Informazione yDipartimento di Informatica e Sistemistica University of Milano Universita’ degli Studi di Roma ”La Sapienza” Via Comelico, 39/41 20135 Milani - Italy Via Salaria 113, 00198 Roma - Italy [email protected] [email protected] zDepartment of Computer Sciences xLIRIS - UFR Informatique Purdue University Universit´eLyon 1 West Lafayette, IN 47907 - USA 43, blvd du 11 novembre 1918 [email protected] 69622 Villeurbanne - France [email protected] Abstract Quality of Service (QoS) is defined as a set of perceivable attributes expressed in a user-friendly language with parameters that may be subjective or objective. Objective parameters are those related to a particular service and are measurable and verifiable. Subjective parameters are those based on the opinions of the end-users. We believe that quality of service should become an integral part of multimedia database systems and users should be able to query by requiring a quality of service from the system. The specification and enforcement of QoS presents an interesting challenge in multi- media systems development. A deal of effort has been done on QoS specification and control at the system and the network levels, but less work has been done at the ap- plication/user level. In this paper, we propose a language, in the style of constraint database languages, for formal specification of QoS constraints. The satisfaction by the system of the user quality requirements can be viewed as a constraint satisfaction problem, and the negotiation can be viewed as constraints relaxation. -

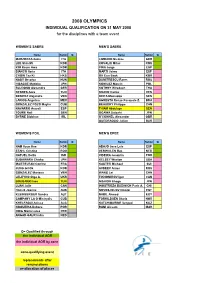

2008 OLYMPICS INDIVIDUAL QUALIFICATION on 31 MAY 2008 for the Disciplines with a Team Event

2008 OLYMPICS INDIVIDUAL QUALIFICATION ON 31 MAY 2008 for the disciplines with a team event WOMEN'S SABRE MEN'S SABRE Name Nation Q Name Nation Q MARZOCCA Gioia ITA LIMBACH Nicolas GER LEE Shin Mi KOR COVALIU Mihai ROU KIM Keum Hwa KOR PINA Jorge ESP BIANCO Ilaria ITA MARTI Jaime ESP CHOW Tsz Ki HKG OH Eun Seok KOR NAGY Orsolya HUN DUMITRESCU Rares ROU HISAGAE Madoka JPN KONIUSZ Marcin POL BUJDOSO Alexandra GER KOTHNY Wiradech THA BESBES Azza TUN BRAVO Carlos VEN BENITEZ Alejandra VEN KEITA Mamadou SEN LARIOS Angelica MEX AGRESTA Renzo Pasquale Z. BRA GONZALEZ POZO Maylin CUB BEAUDRY Philippe CAN NAVARRO Araceli ESP THIAM Abdulaye SEN TOURE Nafi SEN OGAWA Satoshi JPN BYRNE Siobhan IRL O'CONNEL Alexander GBR OUEDRAOGO Julien BUR WOMEN'S FOIL MEN'S EPEE Name Nation Q Name Nation Q NAM Hyun Hee KOR ABAJO Jose Luis ESP STAHL Cristina ROU VERWIJLEN Bas NED HATUEL Delila ISR VIDEIRA Joaquim POR SUGAWARA Chieko JPN KELSEY Weston USA MAITREJEAN Corrine FRA KAUTER Michael SUI JUNG Gil Ok KOR AVDEEV Anton RUS GONZALEZ Mariana VEN WANG Lei CHN LELEYKO Olga A. UKR TIKHOMIROV Igor CAN BOUBAKRI Ines TUN NISHIDA Shogo JPN LUAN Jujie CAN INOSTROZA BUDINICH Paris A. CHI HALLS Joanne AUS NOVOSJOLOV Nikolai EST KLEINBERGER Sandra AUT NABIL Ahmed EGY CAMPANY LA O Misleydis CUB TORKILDSEN Sturla NOR KHELFAOUI Anissa ALG KATCHIOURINE Serguei KGZ NOGUEIRA Debora POR RAMI Aissam MAR DOIG Maria Luisa PER ANGAD-GAUR Indra NED Q= Qualified through the individual AOR the individual AOR by zone zone-qualifying event replacements after renunciations re-allocation -

26Th Summer Universiade SHENZHEN - 2011 Document Engarde-Escrime.Com Mens Foil Team 18/08/2011 08:53 Page 1/1 SHENZHEN CHINA 18 August 2011

26th Summer Universiade SHENZHEN - 2011 Document engarde-escrime.com Mens Foil Team 18/08/2011 08:53 page 1/1 SHENZHEN CHINA 18 August 2011 Tireurs (participants, ordre structuré - 56) série nom prénom équipe 10 HINTERSEER Moritz AUSTRIA 53 POSCHARNIG Johannes AUSTRIA 17 PRANZ Rene AUSTRIA 59 WOHLGEMUTH Dominik AUSTRIA 24 BYK Siarhei BELARUS 54 KURYSHKA Andrei BELARUS 34 ULASIK Yauheni BELARUS 33 CHEN Min CHINA 37 HUANG Liangcai CHINA 2 LEI Sheng CHINA 3 ZHU Jun CHINA 32 LEFORT Enzo FRANCE 28 SARDA Thibault FRANCE 45 SIMON Vincent FRANCE 30 TONY HELISSEY Jean-Paul FRANCE 44 DAVIS James GREAT BRITAIN 36 JEFFERIES Edward GREAT BRITAIN 39 MEPSTEAD Marcus GREAT BRITAIN 6 ROSOWSKY Husayn GREAT BRITAIN 12 STEINER Daniel HUNGARY 57 SZABADOS Kristof HUNGARY 35 SZEKI Bence HUNGARY 11 FOCONI Alessio ITALY 8 LARI Tommaso ITALY 1 MINUTO Martino ITALY 16 SIMONCELLI Luca ITALY 55 AZUMA Jumpei JAPAN 5 FUJINO Daiki JAPAN 75 HIRANO Yoshiki JAPAN 47 ONIZAWA Daima JAPAN 3 HEO Jun KOREA 22 KIM Min Kyu KOREA 42 MOON Kyeong Sik KOREA 52 GLONEK Radoslaw POLAND 15 MAJEWSKI Michal POLAND 29 OSMANSKI Pawel POLAND 27 RAJSKI Leszek POLAND 64 NEW Jarryd SOUTH AFRICA 66 PYM-SILJEUR Skye SOUTH AFRICA 46 VILJOEN Jacques SOUTH AFRICA 23 AKHMATKHUZIN Artur RUSSIA 21 KHOVANSKIY Alexey RUSSIA 41 KOMISSAROV Dmitry RUSSIA 9 ZAPOZDAEV Igor RUSSIA 72 CHOO Yan Long SINGAPORE 65 LAM Matthew Hin Yui SINGAPORE 61 TAN Yuan Zi SINGAPORE 51 ZHANG Zhenggang SINGAPORE 14 HERTSYK Rostyslav UKRAINE 42 POGREBNIAK Andrii UKRAINE 26 SYRACHYNSKYY Pavlo UKRAINE 48 YUNES Klod UKRAINE 25 CALDWELL -

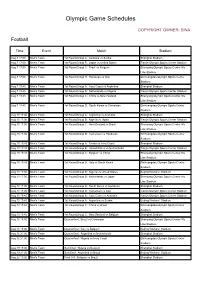

Download Schedule(PDF)

Olympic Game Schedules COPYRIGHT OWNER: SINA Football Time Event Match Stadium Aug.7 17:00 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup A : Australia vs Serbia Shanghai Stadium Aug.7 17:00 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup B : Japan vs United States Tianjin Olympic Sports Center Stadium Aug.7 17:00 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup C : Brazil vs Belgium Shenyang Olympic Sports Center Wu Lihe Stadium Aug.7 17:00 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup D : Honduras vs Italy Qinhuangdao Olympic Sports Center Stadium Aug.7 19:45 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup A : Ivory Coast vs Argentina Shanghai Stadium Aug.7 19:45 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup B : Netherlands vs Nigeria Tianjin Olympic Sports Center Stadium Aug.7 19:45 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup C : China vs New Zealand Shenyang Olympic Sports Center Wu Lihe Stadium Aug.7 19:45 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup D : South Korea vs Cameroon Qinhuangdao Olympic Sports Center Stadium Aug.10 17:00 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup A : Argentina vs Australia Shanghai Stadium Aug.10 17:00 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup B : Nigeria vs Japan Tianjin Olympic Sports Center Stadium Aug.10 17:00 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup C : New Zealand vs Brazil Shenyang Olympic Sports Center Wu Lihe Stadium Aug.10 17:00 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup D : Cameroon vs Honduras Qinhuangdao Olympic Sports Center Stadium Aug.10 19:45 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup A : Serbia vs Ivory Coast Shanghai Stadium Aug.10 19:45 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup B : United States vs Netherlands Tianjin Olympic Sports Center Stadium Aug.10 19:45 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup C : Belgium vs China Shenyang Olympic Sports Center Wu