Deep Impact: Robert Goddard and the Soviet 'Space Fad' of the 1920S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music Performance and Education

SCIENTIFIC JOURNAL OF MUSIC ART AND EDUCATION WORLD BULLETIN “MUSICAL ARTS AND EDUCATION OF THE UNESCO CHAIR IN LIFE-LONG LEARNING” The journal was founded in 2013 comes out 4 times a year Moscow State Pedagogical University was founded 140 years ago Founder: Federal State Budget Educational Institution of Higher Professional Education “Moscow State Pedagogical University” Publisher: “MSPU” Publishing House The co-publisher of the issue: FSBEIHPE “Mordovian State Pedagogical Institute named after M. E. Evsevyev” (branch of the UNESCO Chair “Musical Arts and Education in Life-long Learning” hosted by MordSPU) EDITORIAL BOARD A. L. Semenov (chairman of the board) Academician of Russian Academy of Sciences, Academician of Russian Academy of Education, Professor E. B. Abdullin (vice-chairman of the board) Professor, Doctor of Pedagogical Sciences, Member of the Union of Composers of Russia V. A. Gergiev People's Artist of Russia V. A. Gurevich Professor, Doctor of Arts, Secretary of the Union of Composers of Saint-Petersburg V. V. Kadakin Candidate of Pedagogical Sciences, Honored Worker of Education of the Republic of Mordovia B. M. Nemensky Professor, Academician of the Russian Academy of Education, People's Artist of Russia M. I. Roytershteyn Professor, Composer, Honoured Art Worker of Russia, Candidate of Arts A. S. Sokolov Professor, Doctor of Arts, Member of the Union of Composers of Russia G. M. Tsypin Professor, Doctor of Pedagogical Sciences, Candidate of Arts, Member of the Union of Composers of Russia R. K. Shedrin Composer, People's Artist of the USSR S. B. Yakovenko Professor, Doctor of Arts, People's Artist of Russia EDITORIAL BOARD Nikolaeva E. -

BGRS\SB-2018 MM&Am

11th International Multiconference «Bioinformatics of Genome Regulation and Structure\ Systems Biology», Novosibirsk, Russia, 20 - 25 August 2018 BGRS\SB-2018 MM&HPC-BBB-2018 SBioMed-2018 CSGB-2018 BioGenEvo-2018 SbPCD-2018 FCRW-2018 20 August 08:30-10:00 Registration (House of Scientists SB RAS, main entrance) Coffee-break 10.10–17.30 Plenary session (House of Scientists SB RAS, Large hall) Chairpersons: Prof. Nikolay Kolchanov, Prof. Ralf Hofestädt, Prof. Mikhail Fedoruk 10.10-10.30 Opening Ceremony (House of Scientists SB RAS, Large Hall) 10.30–11.10 Entropic hourglass patterns of animal and plant development and the emergence of biodiversity. Ivo Grosse, Institute of Computer Science, Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, Halle, Germany 11.10–11.50 Selection versus Adaptation: Network Diversification and the Origins of Life, Ageing and Cancer Hans V. Westerhoff, Synthetic Systems Biology and Nuclear Organization, University of Amsterdam 11.50–12.30 Unraveling of gene expression control in genome-reduced bacteria. The rally goes on… Vadim Govorun, Federal Research and Clinical Center of Physical-Chemical Medicine of Federal Medical Biological Agency (RCC PCM FMBA), Russia 12.30–12.45 HPC clusters and Big Data storage for data analysis in scientific research – Huawei experience Alexey Iyudin, Huawei Technologies, Gold Sponsor 12.45–14.30 Lunch + Registration 14.30–15.10 Towards understanding of apoptosis regulation using computational biology Inna N. Lavrik, Department of Translational Inflammation Research, Institute of Experimental -

Peoples, Identities and Regions. Spain, Russia and the Challenges of the Multi-Ethnic State

Institute Ethnology and Anthropology Russian Academy of Sciences Peoples, Identities and Regions. Spain, Russia and the Challenges of the Multi-Ethnic State Moscow 2015 ББК 63.5 УДК 394+312+316 P41 Peoples, Identities and Regions. Spain, Russia and the Challenges of the Multi-Ethnic State / P41 edited by Marina Martynova, David Peterson, Ro- man Ignatiev & Nerea Madariaga. Moscow: IEA RAS, 2015. – 377 p. ISBN 978-5-4211-0136-9 This book marks the beginning of a new phase in what we hope will be a fruitful collaboration between the Institute Ethnology and Anthropology Russian Academy of Science and the University of the Basque Country. Researchers from both Spain and Russia, representing a series of scientific schools each with its own methods and concepts – among them anthropologists, political scien- tists, historians and literary critics-, came to the decision to prepare a collective volume exploring a series of vital issues concerning state policy in complex societies, examining different identitarian characteristics, and reflecting on the difficulty of preserving regional cultures. Though the two countries clearly have their differences – political, economic and social –, we believe that the compar- ative methodology and the debates it leads to are valid and indeed important not just at a theoretical level, but also in practical terms. The decision to publish the volume in English is precisely to enable us to overcome any linguistic barriers there might be between Russian and Spanish academics, whilst simultaneously making these studies accessible to a much wider audience, since the realities be- hind many of the themes touched upon in this volume are relevant in many other parts of the globe beyond our two countries. -

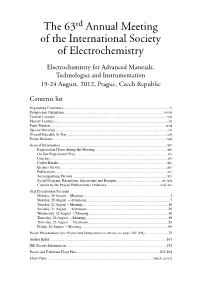

63Rd Annual Meeting Program.Pdf

Program of the 63rd Annual Meeting of the International Society of Electrochemistry iii The 63rd Annual Meeting of the International Society of Electrochemistry Electrochemistry for Advanced Materials, Technologies and Instrumentation 19-24 August, 2012, Prague, Czech Republic Contents list Organizing Committee ...................................................................................................................v Symposium Organizers ...........................................................................................................vi-vii Tutorial Lectures ........................................................................................................................ viii Plenary Lectures ............................................................................................................................ix Prize Winners ............................................................................................................................ x-xi Special Meetings ......................................................................................................................... xii Overall Schedule by Day ........................................................................................................... xiii Poster Sessions ........................................................................................................................... xiii General Information ....................................................................................................................xiv -

Alexander Bolonkin

1 Alexander Bolonkin USSR NASA, USA LIFE. SCIENCE. FUTURE Concentration camp, USSR. New York 2 Alexander Bolonkin LIFE. SCIENCE. FUTURE (Biography notes, researches and innovations. Translation from Russian by Yulia Plotnikov) New York 3 Acknowledgement The author thanks Professor at the University of Perm Oleg Pensky for active endpoint support the publication of this book, Julia Plotnikov for translation and explanation of abbreviations. 4 Contents Preface 6 Part 1. Life in the USSR 7 1. Ancestors.(from the memoirs of sister Anne Bolonkin). 7 2. Childhood 10 3. Perm Aviation College and the Regional Laboratory of model aircraft (1948-52) 15 4. Kazan Aviation Institute (KAI, 1952-1958) 19 5. Experimental Design Bureau of O.K. Antonov 27 6. Doctoral Dissertation. Moscow Aviation Institute. 37 7. Experimental Design Bureau of V.P. Glushko 40 8. Moon Race 48 9. Moscow Aviation Technology Institute (MATI). Moscow Higher Technical University named Bauman (MHTU) 61 10. Post-Doctoral dissertation 62 Part2. In Soviet Concentration Camps 67 1. Preface 68 2. Acceding to remedial activity 68 3. Propaganda leaflets 73 4. Arrest, investigation 73 5. Trial 76 6. Concentration camp JH-389/17а 77 7. Concentration camp hospital 78 8. Concentration camp JH-389/19 82 9. Penalty isolation ward and penalty cell (special prison) 84 10. Concentration camp in Barashevo 85 11. Road to exile 89 12. First exile 90 13. Second arrest 98 14. Ulan-Ude prison 99 15. Second trial. Concentration camp ОV-94/2 102 16. Third arrest and fabrication of a damning ―new case‖ 105 17. Second exile. 107 APPENDIX #1 according to the materials of radio station ―Svoboda‖/(―Freedom‖) 111. -

Buklet Tam Vdaleke110621 (2).Pdf

Information about the film Annotation Release year: 2021 Length: 14 min The film is dedicated to the memory of Priest Martyr Documentary Michael Belorrosov who glorified God with his life and death. No one played any roles, we simply tried to imagine Director and script writer – Victoria Fomina his last day. Cameraman and director, post-production artist – Maksim It happened 100 years ago. The action begins in 1920 and Orekhov continues to recent events when Priest Martyr Michael Cameraman – Jacob (Aleksander) Brooks Belorrosov appeared in a dream to Colonel Sergei Songwriter – Vadim Kuzmin (1963 – 2012) Evgenevich Dontsov and helped him to rebuilt a church. Sound engineer – Anna Freidman Post-production manager – Marina Kruchenova Editor – Marina Turovskaya Placard – Georgii Petrov The following took part in the filming: Archpriest George Yudin; Priest Nicholas, Matushka Natalia, and Maria Bushe; Sergei Dontsov; Michael, Galina, and Ksenia Kolomytsev; Svetlana, Tatiana, and Sofia Komov; Lev and Nicholas Noskov; Evgenii Zaraiskii; Aleksander Gromov; Maria Abramyan; Rodeo and other animals from the Kuznetsovo farm Film produced by Autonomous Nonprofit Organization «Studio «Other Haven». Film produced within the framework of the Media Museum on the Spiritual History of the town of Romanov- Rights to the film owned by ANO Studio« «Other Haven» Borisoglebsk and the financial support from the Fund of Presidential Grants PRIEST MARTYR MICHAEL BELORROSOV about the authors Michael Belorossov was born on Victoria Fomina – graduated from the May11, 1869, into the family of Department of Physics at Moscow Deacon Pavel Belorossov a year after State University’s branch of Theoretical he had been ordained and assigned Physics, defended a dissertation at to serve in the Church of the Savior the All-Russia State Institute of in Romanov. -

Premium № 4 АПРЕЛЬ | APRIL 2015

ВАШ ПЕРСОНАЛЬНЫЙ ЭКЗЕМПЛЯР | YOUR PERSONAL COPY БОРТОВОЙ ЖУРНАЛ | INFLIGHT MAGAZINE Premium № 4 АПРЕЛЬ | APRIL 2015 48 PAGES IN ENGLISH INSIDE ВСЕ МАШИНЫ ВЕСНЫ ЭЛЬЗАС. ПУТЕШЕСТВИЕ BEST OF THE BEST. РОССИЯ МОРСКАЯ. К СЕРДЦУ ЕВРОПЫ МИРОВЫЕ ОТЕЛЬНЫЕ СЕТИ ФОТОРЕПОРТАЖ и с т о р и я у с п е х а АКАДЕМИК, КОСМОС И ТРОИЦА БОРИС РАУШЕНБАХ ИЗ ЛЕГЕНДАРНОЙ ПЛЕЯДЫ УЧЕНЫХ — ОСНОВОПОЛОЖНИКОВ СОВЕТСКОЙ КОСМОНАВТИКИ, СОЗДАТЕЛЬ ОРИГИНАЛЬНОЙ ШКОЛЫ КОСМИЧЕСКОЙ НАВИГАЦИИ. НА ПИКЕ НАУЧНОЙ КАРЬЕРЫ АКАДЕМИК РАУШЕНБАХ НА ПЕРВЫЙ ВЗГЛЯД НЕОЖИДАННО ЗАНЯЛСЯ ПРОБЛЕМОЙ ХУДОЖЕСТВЕННОЙ ПЕРСПЕКТИВЫ И ПОСТРОИЛ ТЕОРИЮ ПРОСТРАНСТВА РУССКОЙ ИКОНЫ текст д м и т р и й с т а х о в Борис Раушенбах говорил, что он «довольно редкий Снимая угол в московской коммуналке, Борис экземпляр царского еще „производства“». Родился он познакомился с соседкой Верой Иванченко, сиротой, 5 января 1915 года в Петрограде, в немецкой семье. племянницей репрессированного руководителя Вос- Отец, инженер Виктор Якобович, руководитель коже- токостали. Веру вселили в небольшую комнату, пере- венного производства фабрики «Скороход», был из по- везя туда часть мебели из квартиры дяди; Борис Викто- волжских немцев. Мать, Леонтина Фридриховна, урож- рович позже шутил: «Мне жена была доставлена на дом денная Галлик, — из эстонских. на автомашине, со всем имуществом. Сильно упростил Уже в детстве Борис задавался вопросом: что НКВД мою жизнь». В мае 1941 года сыграли свадьбу. лучше — пользоваться сделанным другими или делать А в начале 1942-го Раушенбаха, как и большинство муж- самому? В ту пору летчики были сродни былинным чин-немцев, мобилизовали и отправили работать на героям и мальчишки бредили небом. В разговоре кирпичный завод на Северном Урале. с девочкой, спросившей, что он будет делать по окон- Он уцелел случайно, но при этом убеждал товари- чании школы, Борис сказал, что его интересует авиа- щей по несчастью, что посадили их оправданно («Идет ция. -

Rockets and People Volume IV:The Moon Race ISBN 978-0-16-089559-3 F Ro As El T Yb Eh S Epu Ir Tn E Edn Tn Fo D Co Mu E Tn .U S S G

Rockets and People Volume IV:The Moon Race ISBN 978-0-16-089559-3 F ro as el t yb eh S epu ir tn e edn tn fo D co mu e tn .U s S G , . evo r emn tn P ir tn i O gn eciff I tn re en :t skoob t ro e . opg . vog enohP : lot l f eer ( 668 ) 215 - 0081 ; D C a er ( a 202 ) 15 -2 0081 90000 aF :x ( 202 ) 215 - 4012 aM :li S t I po CCD W , ihsa gn t no D , C 0402 -2 1000 ISBN 978-0-16-089559-3 9 780160 895593 ISBN 978-0-16-089559-3 F ro leas b y t eh S pu e ri tn e dn e tn D fo co mu e tn s , .U Svo . e G r mn e tn P ri tn i gn fficeO I tn er en t: koob s t ro e. opg . vog : Plot l nohf ree e ( 668 ) 215 - 0081 ; C Da re a ( 202 ) 15 -2 0081 90000 Fa :x ( 202 ) 215 - 4012 il:M S a t po DCI C, W a hs i gn t no , D C 0402 -2 1000 ISBN 978-0-16-089559-3 9 780160 895593 Rockets and People Volume IV:The Moon Race Boris Chertok Asif Siddiqi, Series Editor The NASA History Series National Aeronautics and Space Administration Office of Communications History Program Office Washington, DC NASA SP-2011-4110 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chertok, B. E. -

Philosophy & Cosmology

INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY OF PHILOSOPHY AND COSMOLOGY PHILOSOPHY & COSMOLOGY Volume 21 Kyiv, 2018 Philosophy and Cosmology, Volume 21 The Academic Journal ISSN 2518-1866 (Online), ISSN 2307-3705 (Print) The State Registration Certificate of the print media КВ №20780-10580Р, June 25 2014 http://ispcjournal.org/ E-mail: [email protected] Printed in the manner of scientific-theoretical digest “Philosophy & Cosmology” since 2004. Printed in the manner of Academic Yearbook of Philosophy and Science “Философия и космология/Philosophy & Cosmology” since 2011. Printed in the manner of Academic Journal “Philosophy & Cosmology” since Volume 12, 2014. Printed according to resolution of Scientific Board of International Society of Philosophy and Cosmology (Minutes of meeting No. 23 from August 15, 2018) Editor-in-Chief Oleg Bazaluk, Doctor of Philosophical Sciences, Professor Editorial Board Gennadii Aliaiev, Doctor of Philosophical Sciences, Professor (Deputy Editor-in-Chief, Ukraine) Eugene Afonasin, Doctor of Philosophical Sciences, Professor (Russia) Anna Brodsky, PhD, Professor (USA) Javier Collado-Ruano, PhD, Professor (Brazil) Kevin Crotty, PhD, Professor (USA) Leonid Djakhaia, Doctor of Philosophical Sciences, Professor (Georgia) Panos Eliopoulos, PhD, Professor (Greece) Georgi Gladyshev, Doctor of Chemical Sciences, Professor (USA) Aleksandr Khazen, PhD (USA) Sergey Krichevskiy, Doctor of Philosophical Sciences, Professor (Russia) Akop Nazaretyan, Doctor of Philosophical Sciences, Professor (Russia) Viktor Okorokov, Doctor of Philosophical -

Rockets and People

Rockets and People Volume III:Hot Days of the Cold War For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office ISBN 978-0-16-081733-5 Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 9 0 0 0 0 Fax: (202) 512-2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402-0001 ISBN 978-0-16-081733-5 9 780160 817335 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office ISBN 978-0-16-081733-5 Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 9 0 0 0 0 Fax: (202) 512-2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402-0001 ISBN 978-0-16-081733-5 9 780160 817335 Rockets and People Volume III:Hot Days of the Cold War Boris Chertok Asif Siddiqi, Series Editor The NASA History Series National Aeronautics and Space Administration NASA History Division Office of External Relations Washington, DC May 2009 NASA SP-2009-4110 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chertok, B. E. (Boris Evseevich), 1912– [Rakety i lyudi. English] Rockets and People: Hot Days of the Cold War (Volume III) / by Boris E. Chertok ; [edited by] Asif A. Siddiqi. p. cm. — (NASA History Series) (NASA SP-2009-4110) Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Chertok, B. E. (Boris Evseevich), 1912– 2. Astronautics— Soviet Union—Biography. 3. Aerospace engineers—Soviet Union— Biography. 4. Astronautics—Soviet Union—History. I. Siddiqi, Asif A., 1966– II. Title. III. Series. IV. SP-2009-4110. TL789.85.C48C4813 2009 629.1’092—dc22 2009020825 I dedicate this book to the cherished memory of my wife and friend, Yekaterina Semyonova Golubkina.