Trauma Emergencies with Management of Specific Injuries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saving Smiles Avulsion Pathway (Page 20) Saving Smiles: Fractures and Displacements (Page 22)

Greater Manchester Local Dental Network SavingSmiles Improving outcomes following dental trauma First Edition I Spring 2017 Practitioners’ Toolkit Contents 04 Introduction to the toolkit from the GM Trauma Network 06 History & examination 10 Maxillo-facial considerations 12 Classification of dento-alveolar injuries 16 The paediatric patient 18 Splinting 20 The AVULSED Tooth 22 The BROKEN Tooth 23 Managing injuries with delayed presentation SavingSmiles 24 Follow up Improving outcomes 26 Long term consequences following dental trauma 28 Armamentarium 29 When to refer 30 Non-accidental injury 31 What should I do if I suspect dental neglect or abuse? 34 www.dentaltrauma.co.uk 35 Additional reference material 36 Dental trauma history sheet 38 Avulsion pathways 39 Fractues and displacement pathway 40 Fractures and displacements in the primary dentition 41 Acknowledgements SavingSmiles Improving outcomes following dental trauma Ambition for Greater Manchester Introduction to the Toolkit from The GM Trauma Network wish to work with our colleagues to ensure that: the GM Trauma Network • All clinicians in GM have the confidence and knowledge to provide a timely and effective first line response to dental trauma. • All clinicians are aware of the need for close monitoring of patients following trauma, and when to refer. The Greater Manchester Local Dental Network (GM LDN) has established a ‘Trauma Network’ sub-group. The • All settings have the equipment described within the ‘armamentarium’ section of this booklet to support optimal treatment. Trauma Network was established to support a safer, faster, better first response to dental trauma and follow up care across GM. The group includes members representing general dental practitioners, commissioners, To support GM practitioners in achieving this ambition, we will be working with Health Education England to provide training days and specialists in restorative and paediatric dentistry, and dental public health. -

Blunt and Blast Head Trauma: Different Entities

International Tinnitus Journal, Vol. 15, No. 2, 115–118 (2009) Blunt and Blast Head Trauma: Different Entities Michael E. Hoffer,1 Chadwick Donaldson,1 Kim R. Gottshall1, Carey Balaban,2 and Ben J. Balough1 1 Spatial Orientation Center, Department of Otolaryngology, Naval Medical Center San Diego, San Diego, California, and 2 Department of Otolaryngology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA Abstract: Mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) caused by blast-related and blunt head trauma is frequently encountered in clinical practice. Understanding the nuances between these two distinct types of injury leads to a more focused approach by clinicians to develop better treat- ment strategies for patients. In this study, we evaluated two separate cohorts of mTBI patients to ascertain whether any difference exists in vestibular-ocular reflex (VOR) testing (n ϭ 55 en- rolled patients: 34 blunt, 21 blast) and vestibular-spinal reflex (VSR) testing (n ϭ 72 enrolled patients: 33 blunt, 39 blast). The VOR group displayed a preponderance of patients with blunt mTBI, demonstrating normal to high-frequency phase lag on rotational chair testing, whereas patients experiencing mTBI from blast-related causes revealed a trend toward low-frequency phase lag on evaluation. The VSR cohort showed that patients with posttraumatic migraine- associated dizziness tended to test higher on posturography. However, an indepth look at the total patient population in this second cohort reveals that a higher percentage of blast-exposed patients exhibited a significantly increased latency on motor control testing as compared to pa- tients with blunt head injury ( p Ͻ .02). These experiments identify a distinct difference be- tween blunt-injury and blast-injury mTBI patients and provide evidence that treatment strategies should be individualized on the basis of each mechanism of injury. -

Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Root Resorption After Dental Trauma: a Systematic Scoping Review Kerstin M

Galler et al. BMC Oral Health (2021) 21:163 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-021-01510-6 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Pathophysiological mechanisms of root resorption after dental trauma: a systematic scoping review Kerstin M. Galler1*, Eva‑Maria Grätz1, Matthias Widbiller1 , Wolfgang Buchalla1 and Helge Knüttel2 Abstract Background: The objective of this scoping review was to systematically explore the current knowledge of cellular and molecular processes that drive and control trauma‑associated root resorption, to identify research gaps and to provide a basis for improved prevention and therapy. Methods: Four major bibliographic databases were searched according to the research question up to Febru‑ ary 2021 and supplemented manually. Reports on physiologic, histologic, anatomic and clinical aspects of root resorption following dental trauma were included. Duplicates were removed, the collected material was screened by title/abstract and assessed for eligibility based on the full text. Relevant aspects were extracted, organized and summarized. Results: 846 papers were identifed as relevant for a qualitative summary. Consideration of pathophysiological mechanisms concerning trauma‑related root resorption in the literature is sparse. Whereas some forms of resorption have been explored thoroughly, the etiology of others, particularly invasive cervical resorption, is still under debate, resulting in inadequate diagnostics and heterogeneous clinical recommendations. Efective therapies for progres‑ sive replacement resorptions have not been established. Whereas the discovery of the RANKL/RANK/OPG system is essential to our understanding of resorptive processes, many questions regarding the functional regulation of osteo‑/ odontoclasts remain unanswered. Conclusions: This scoping review provides an overview of existing evidence, but also identifes knowledge gaps that need to be addressed by continued laboratory and clinical research. -

Patient Assessment?

EMERGENCY MEDICAL TECHNICIAN ‐ BASIC What is Patient Assessment? Why is Patient Assessment important? MECTA EMS Learning Assistant 2 What are the phases of patient assessment? Review of Dispatch Information Scene Survey Initial Assessment Focused History and Physical Exam Detailed Physical Exam Ongoing Assessment Communication Documentation MECTA EMS Learning Assistant 3 Why is the order of Patient Assessment important? Why is it necessary to develop a method of assessment and use that method on all patients? MECTA EMS Learning Assistant 4 SCENE SIZE‐UP INITIAL ASSESSMENT Trauma FOCUSED HISTORY & FOCUSED HISTORY & PHYSICAL EXAM PHYSICAL EXAM Patient Patient DETAILED DETAILED PHYSICAL EXAM PHYSICAL EXAM Medical ON‐GOING ASSESSMENT MECTA EMS Learning Assistant 5 Begin with receipt of call Location Incident Injured/Injuries MECTA EMS Learning Assistant 6 Continue En Route Further info from dispatcher Observe ▪ Smoke? ▪ Fire? ▪ High line wires? ▪ Railroads? ▪ Water? ▪ Industry? ▪ Other Public Safety units? MECTA EMS Learning Assistant 7 Upon Arrival Observe ▪ Overall scene ▪ Location of victim(s) ▪ Possible Mechanisms of Injury MECTA EMS Learning Assistant 8 Upon Arrival Observe ▪ Hazards ▪ Crowds ▪ HazMat ▪ Electricity ▪ Gas ▪ Fire ▪ Glass ▪ Jagged metal ▪ Stability of environment ▪ Traffic ▪ Environment MECTA EMS Learning Assistant 9 Ensure Safety ▪ Yourself ▪ Partner ▪ Other rescuers/Bystanders ▪ Patient MECTA EMS Learning Assistant 10 Call for assistance ▪ Other EMS Units ▪ Law Enforcement ▪ Fire Department ▪ -

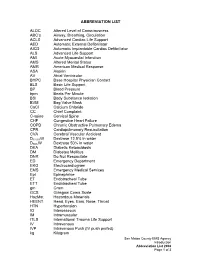

ABBREVIATION LIST ALOC Altered Level of Consciousness ABC's Airway, Breathing, Circulation ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Suppo

ABBREVIATION LIST ALOC Altered Level of Consciousness ABC’s Airway, Breathing, Circulation ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Support AED Automatic External Defibrillator AICD Automatic Implantable Cardiac Defibrillator ALS Advanced Life Support AMI Acute Myocardial Infarction AMS Altered Mental Status AMR American Medical Response ASA Aspirin AV Atrial Ventricular BHPC Base Hospital Physician Contact BLS Basic Life Support BP Blood Pressure bpm Beats Per Minute BSI Body Substance Isolation BVM Bag Valve Mask CaCl Calcium Chloride CC Chief Complaint C-spine Cervical Spine CHF Congestive Heart Failure COPD Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Edema CPR Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation CVA Cerebral Vascular Accident D12.5%W Dextrose 12.5% in water D50%W Dextrose 50% in water DKA Diabetic Ketoacidosis DM Diabetes Mellitus DNR Do Not Resuscitate ED Emergency Department EKG Electrocardiogram EMS Emergency Medical Services Epi Epinephrine ET Endotracheal Tube ETT Endotracheal Tube gm Gram GCS Glasgow Coma Scale HazMat Hazardous Materials HEENT Head, Eyes, Ears, Nose, Throat HTN Hypertension IO Interosseous IM Intramuscular ITLS International Trauma Life Support IV Intravenous IVP Intravenous Push (IV push prefed) kg Kilogram San Mateo County EMS Agency Introduction Abbreviation List 2008 Page 1 of 3 J Joule LOC Loss of Consciousness Max Maximum mcg Microgram meds Medication mEq Milliequivalent min Minute mg Milligram MI Myocardial Infarction mL Milliliter MVC Motor Vehicle Collision NPA Nasopharyngeal Airway NPO Nothing Per Mouth NS Normal Saline NT Nasal Tube NTG Nitroglycerine NS Normal Saline O2 Oxygen OB Obstetrical OD Overdose OPA Oropharyngeal Airway OPQRST Onset, Provoked, Quality, Region and Radiation, Severity, Time OTC Over the Counter PAC Premature Atrial Contraction PALS Pediatric Advanced Life Support PEA Pulseless Electrical Activity PHTLS Prehospital Trauma Life Support PID Pelvic Inflammatory Disease PO By Mouth Pt. -

Isolated Severe Blunt Traumatic Brain Injury: Effect of Obesity on Outcomes

CLINICAL ARTICLE J Neurosurg 134:1667–1674, 2021 Isolated severe blunt traumatic brain injury: effect of obesity on outcomes Jennifer T. Cone, MD, MHS,1 Elizabeth R. Benjamin, MD, PhD,2 Daniel B. Alfson, MD,2 and Demetrios Demetriades, MD, PhD2 1Department of Surgery, Section of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, University of Chicago, Illinois; and 2Department of Surgery, Division of Trauma, Emergency Surgery, and Surgical Critical Care, LAC+USC Medical Center, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California OBJECTIVE Obesity has been widely reported to confer significant morbidity and mortality in both medical and surgical patients. However, contemporary data indicate that obesity may confer protection after both critical illness and certain types of major surgery. The authors hypothesized that this “obesity paradox” may apply to patients with isolated severe blunt traumatic brain injuries (TBIs). METHODS The Trauma Quality Improvement Program (TQIP) database was queried for patients with isolated severe blunt TBI (head Abbreviated Injury Scale [AIS] score 3–5, all other body areas AIS < 3). Patient data were divided based on WHO classification levels for BMI: underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2), obesity class 1 (30.0–34.9 kg/m2), obesity class 2 (35.0–39.9 kg/m2), and obesity class 3 (≥ 40.0 kg/ m2). The role of BMI in patient outcomes was assessed using regression models. RESULTS In total, 103,280 patients were identified with isolated severe blunt TBI. Data were excluded for patients aged < 20 or > 89 years or with BMI < 10 or > 55 kg/m2 and for patients who were transferred from another treatment center or who showed no signs of life upon presentation, leaving data from 38,446 patients for analysis. -

Career Technical Credit Transfer (CT²) Emergency Medical Technician-Basic (EMT-B) Career Technical Assurance Guide (CTAG) October 17, 2008

Adopted Career Technical Credit Transfer (CT²) Emergency Medical Technician-Basic (EMT-B) Career Technical Assurance Guide (CTAG) October 17, 2008 The following course or Career-Technical Assurance Number (CTAN) is eligible for transfer between career-technical education, adult workforce education, and post-secondary education. CTEMTB002 – Emergency Medical Technician – Basic (EMT-B) Credits: 7 Semester/10 Quarter Hours Advising Notes: Submitted course work must include proof of laboratory and clinical components. Those persons holding current Ohio certification as an EMT-Basic will be given what the receiving institution is offering as credit for its CT² approved EMT-B course. The awarding of credit for the EMT-B course of s t u d y m a y decrease the time to associate degree completion, when such a degree is offered, but will not replace any portion of the EMT-Intermediate or EMT- Paramedic curricula as the later two are separate courses of study. Prerequisite: Current Ohio EMT-Basic Certification Module I Preparatory Module II Patient Assessment Module III Airway and Cardiac Arrest Management Module IV Trauma Patient Management Module V Medical Patient Management Clinical Experience and/or Pre-Hospital Internship Minimum Hours = 120 Didactic 10 Clinical Experience and/or Pre-Hospital Internship Note: Credit hours assigned to CTANs are “relative values,” which are used to help determine the equivalency of submitted coursework or content. Once approved by a validation panel as a CT² course, students will be given what the receiving institution is offering as credit for its CT² approved course. The CTAN illustrates the learning outcomes that are equivalent or common in introductory technical courses. -

NY State-Wide EMT/AEMT BLS Protocols

STATE OF NEW YORK DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH Corning Tower The Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller Empire State Plaza Albany, New York 12237 Antonia C. Novello, M.D., M.P.H., Dr.P.H. Dennis P. Whalen Commissioner Executive Deputy Commissioner February 1, 2003 Dear EMS Agency: EMS Agencies and Course Sponsors in the State of New York will be receiving copies of the 2003 version of the New York State Basic Life Support Protocols for Emergency Medical Technicians and Advanced Emergency Medical Technicians. The protocols were developed by the State Emergency Medical Advisory Committee and approved by the State EMS Council. The new protocols have been updated to meet the current standard of care within New York State and to reflect all recent curriculum changes. These new protocols do not pertain to Certified First Responders. A separate protocol book for CFRs is in the final development stages at the State Emergency Medical Advisory Committee. Until the new CFR protocols are released, CFRs may use the new EMT/AEMT BLS protocols up to their level of training and scope of care within the State of New York. CFRs may also refer to their Regional Emergency Medical Advisory Committee and their agency Medical Director for clarification and advise. The new EMT/AEMT BLS protocols will be implemented in the following manner: 1. First, all EMS agencies in New York State must update all of their NYS EMS certified personnel to the new protocols by August 1st, 2003. On August 1st, 2003 the protocols will be in use by all EMS agencies across the state. -

Guideline on Management of Acute Dental Trauma

rEfErence manual v 32 / No 6 10 / 11 Guideline on Management of Acute Dental Trauma Originating Council Council on Clinical Affairs Review Council Council on Clinical Affairs Adopted 2001 Revised 2004, 2007, 2010 Purpose violence, and sports.7-10 All sporting activities have an asso- The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) ciated risk of orofacial injuries due to falls, collisions, and intends these guidelines to define, describe appearances, and contact with hard surfaces.11 The AAPD encourages the use set forth objectives for general management of acute trau- of protective gear, including mouthguards, which help dis- matic dental injuries rather than recommend specific treat- tribute forces of impact, thereby reducing the risk of severe ment procedures that have been presented in considerably injury.13,14 more detail in text-books and the dental/medical literature. Dental injuries could have improved outcomes if the public were aware of first-aid measures and the need to seek Methods immediate treatment.14-17 Because optimal treatment results This guideline is an update of the previous document re- follow immediate assessment and care,18 dentists have an vised in 2007. It is based on a review of the current dental ethical obligation to ensure that reasonable arrangements and medical literature related to dental trauma. An elec- for emergency dental care are available.19 The history, cir- tronic search was conducted using the following parameters: cumstances of the injury, pattern of trauma, and behavior Terms: “teeth”, “trauma”, “permanent teeth”, and “primary of the child and/or caregiver are important in distin- teeth”; Field: all fields; Limits: within the last 10 years; guishing nonabusive injuries from abuse.20 humans; English. -

Emergency Care

Emergency Care THIRTEENTH EDITION CHAPTER 14 The Secondary Assessment Emergency Care, 13e Copyright © 2016, 2012, 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. Daniel Limmer | Michael F. O'Keefe All Rights Reserved Multimedia Directory Slide 58 Physical Examination Techniques Video Slide 101 Trauma Patient Assessment Video Slide 148 Decision-Making Information Video Slide 152 Leadership Video Slide 153 Delegating Authority Video Emergency Care, 13e Copyright © 2016, 2012, 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. Daniel Limmer | Michael F. O'Keefe All Rights Reserved Topics • The Secondary Assessment • Body System Examinations • Secondary Assessment of the Medical Patient • Secondary Assessment of the Trauma Patient • Detailed Physical Exam continued on next slide Emergency Care, 13e Copyright © 2016, 2012, 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. Daniel Limmer | Michael F. O'Keefe All Rights Reserved Topics • Reassessment • Critical Thinking and Decision Making Emergency Care, 13e Copyright © 2016, 2012, 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. Daniel Limmer | Michael F. O'Keefe All Rights Reserved The Secondary Assessment Emergency Care, 13e Copyright © 2016, 2012, 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. Daniel Limmer | Michael F. O'Keefe All Rights Reserved Components of the Secondary Assessment • Physical examination • Patient history . History of the present illness (HPI) . Past medical history (PMH) • Vital signs continued on next slide Emergency Care, 13e Copyright © 2016, 2012, 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. Daniel Limmer | Michael F. O'Keefe All Rights Reserved Components of the Secondary Assessment • Sign . Something you can see • Symptom . Something the patient tell you • Reassessment is a continual process. Emergency Care, 13e Copyright © 2016, 2012, 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. Daniel Limmer | Michael F. O'Keefe All Rights Reserved Techniques of Assessment • History-taking techniques . -

Patient Assessment-Trauma.Pub

Patient Assessment –Trauma 1 - Scene Size-Up • Body Substance Isolation [INCLUDES, BUT NOT LIMITED TO: GLOVES, MASK, GOWN, HEPA MASK] • Assess for scene safety [IF THE SCENE IS UNSAFE RETREAT TO A SAFE DISTANCE] • Identify Mechanism of Injury (MOI) Age, gender and race • Identify number of patients information • Determine need for additional resources [OTHER BLS, ALS, FD, PD, ETC.] may be used • Application of cervical spine immobilization, as necessary [MANUAL OR MECHANICAL] to identify a patient whose name cannot be 2 - Initial Assessment determined. • General Impression ♦Age, gender, race, position found ♦Determine MOI, if not already done A patient’s ♦Locate and treat life threats/quick CPR Check [EXSANGUINATING BLEEDING, NO PULSE OR RESPIRATIONS, ETC.] dentures ♦Verbalize a general impression of patient [“PALE LOOKING 35 Y/O MALE, BLEEDING FROM FOREHEAD”] may block the airway if • Mental Status they are not ♦ securely in place. Check for responsiveness, if not readily apparent ♦ Determine mental status/level of consciousness (LOC) on AVPU Scale Alert - correctly answers three questions related to Person, Place and Time Verbal - does not correctly answer all of above questions OR the patient only responds to verbal commands To better assess Pain - only responds to painful stimuli the Unresponsive - does not respond to any stimuli chest ♦ Determine chief complaint, if possible during the Initial Assessment, listen • Airway for lung sounds at ♦ the mid-axillary Can patient speak or cry? line. ♦ Are there any unusual breathing sounds? -

Pediatric Orbital Fractures

Review Article 9 Pediatric Orbital Fractures Adam J. Oppenheimer, MD1 Laura A. Monson, MD1 Steven R. Buchman, MD1 1 Section of Plastic Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Address for correspondence and reprint requests Steven R. Buchman, Michigan Hospitals, Ann Arbor, Michigan MD, Section of Plastic Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Michigan Health System, 2130 Taubman Center, SPC 5340, Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstruction 2013;6:9–20 1500 E. Medical Center Drive, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-5340 (e-mail: [email protected]). Abstract It is wise to recall the dictum “children are not small adults” when managing pediatric Keywords orbital fractures. In a child, the craniofacial skeleton undergoes significant changes in ► orbit size, shape, and proportion as it grows into maturity. Accordingly, the craniomaxillo- ► pediatric facial surgeon must select an appropriate treatment strategy that considers both the ► trauma nature of the injury and the child’s stage of growth. The following review will discuss the ► enophthalmos management of pediatric orbital fractures, with an emphasis on clinically oriented ► entrapment anatomy and development. Pediatric orbital fractures occur in discreet patterns, based on 12 years of age. During mixed dentition, the cuspid teeth are the characteristic developmental anatomy of the craniofacial immediately beneath the orbit: hence the term eye tooth in skeleton at the time of injury. To fully understand pediatric dental parlance. It is not until age 12 that the maxillary sinus orbital trauma, the craniomaxillofacial surgeon must first be expands, in concert with eruption of the permanent denti- aware of the anatomical and developmental changes that tion. At 16 years of age, the maxillary sinus reaches adult size occur in the pediatric skull.