45-20 Rorient 72 Z. 2-19.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

INDEX Aodayixike Qingzhensi Baisha, 683–684 Abacus Museum (Linhai), (Ordaisnki Mosque; Baishui Tai (White Water 507 Kashgar), 334 Terraces), 692–693 Abakh Hoja Mosque (Xiang- Aolinpike Gongyuan (Olym- Baita (Chowan), 775 fei Mu; Kashgar), 333 pic Park; Beijing), 133–134 Bai Ta (White Dagoba) Abercrombie & Kent, 70 Apricot Altar (Xing Tan; Beijing, 134 Academic Travel Abroad, 67 Qufu), 380 Yangzhou, 414 Access America, 51 Aqua Spirit (Hong Kong), 601 Baiyang Gou (White Poplar Accommodations, 75–77 Arch Angel Antiques (Hong Gully), 325 best, 10–11 Kong), 596 Baiyun Guan (White Cloud Acrobatics Architecture, 27–29 Temple; Beijing), 132 Beijing, 144–145 Area and country codes, 806 Bama, 10, 632–638 Guilin, 622 The arts, 25–27 Bama Chang Shou Bo Wu Shanghai, 478 ATMs (automated teller Guan (Longevity Museum), Adventure and Wellness machines), 60, 74 634 Trips, 68 Bamboo Museum and Adventure Center, 70 Gardens (Anji), 491 AIDS, 63 ack Lakes, The (Shicha Hai; Bamboo Temple (Qiongzhu Air pollution, 31 B Beijing), 91 Si; Kunming), 658 Air travel, 51–54 accommodations, 106–108 Bangchui Dao (Dalian), 190 Aitiga’er Qingzhen Si (Idkah bars, 147 Banpo Bowuguan (Banpo Mosque; Kashgar), 333 restaurants, 117–120 Neolithic Village; Xi’an), Ali (Shiquan He), 331 walking tour, 137–140 279 Alien Travel Permit (ATP), 780 Ba Da Guan (Eight Passes; Baoding Shan (Dazu), 727, Altitude sickness, 63, 761 Qingdao), 389 728 Amchog (A’muquhu), 297 Bagua Ting (Pavilion of the Baofeng Hu (Baofeng Lake), American Express, emergency Eight Trigrams; Chengdu), 754 check -

Beijing, a Garden of Violence

Inter-Asia Cultural Studies ISSN: 1464-9373 (Print) 1469-8447 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/riac20 Beijing, a garden of violence Geremie R. Barmé To cite this article: Geremie R. Barmé (2008) Beijing, a garden of violence, Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 9:4, 612-639, DOI: 10.1080/14649370802386552 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14649370802386552 Published online: 15 Nov 2008. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 153 View related articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=riac20 Download by: [Australian National University] Date: 08 April 2016, At: 20:00 Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, Volume 9, Number 4, 2008 Beijing, a garden of violence Geremie R. BARMÉ TaylorRIAC_A_338822.sgm10.1080/14649370802386552Inter-Asia1464-9373Original200894000000DecemberGeremieBarmé[email protected] and& Article Francis Cultural (print)/1469-8447Francis 2008 Studies (online) ABSTRACT This paper examines the history of Beijing in relation to gardens—imperial, princely, public and private—and the impetus of the ‘gardener’, in particular in the twentieth-century. Engag- ing with the theme of ‘violence in the garden’ as articulated by such scholars as Zygmunt Bauman and Martin Jay, I reflect on Beijing as a ‘garden of violence’, both before the rise of the socialist state in 1949, and during the years leading up to the 2008 Olympics. KEYWORDS: gardens, violence, party culture, Chinese history, Chinese politics, cultivation, revolution The gardening impulse This paper offers a brief examination of the history of Beijing in relation to gardens— imperial, princely, socialist, public and private—and the impetus of the ‘gardener’, in particular during the twentieth century. -

True Model of a Natural Chan Practitioner

NCOUNTERS with Master E Ⅹ Sheng Yen Encounters with Master Sheng Yen Ⅹ Pocket Guides to Buddhist Wisdom E-26 Publisher: Dharma Drum Mountain Culture and Educational Foundation 5F., No. 186, Gongguan Rd., Beitou District Taipei City 112-44, Taiwan Tel: 886-2-2893-4646 Fax: 886-2-2896-0731 www.ddm.org.tw Speakers: Du Zhengmin, Ding Min, Shan Te-hsing Editorial & Production: Cultural Center, Dharma Drum Mountain Revision: International Translation Office ISBN: 978-986-96684-4-6 1st Edition: March 2019 Preface o share with the public the thoughts and life experiences Tof Dharma Drum Mountain founder Master Sheng Yen (also known as Shifu, meaning “Master”), the Sheng Yen Education Foundation embarked on a series of talks beginning in September of 2009. Fifty-two talks were given at the Sheng Yen Lecture Hall (located in the official residence where Master Sheng Yen lived in his final years). The talks were titled A Living Example, Countless Teachings— Encounters with Master Sheng Yen and we invited all his monastic and lay disciples to share with us their stories about Shifu, how he taught them through his living example and words. Listening to these speakers’ personal accounts of the interactions between teacher and student allowed the audience to commemorate Master Sheng Yen’s journey, and once again hear his gracious teachings. The talks include stories of Master Sheng Yen’s everyday life, how he would give detailed guidance to his disciples regarding their speech and actions. There are also accounts of his travels to share the Buddhadharma locally and overseas, reaching out to the public, and teaching them skillfully and flexibly based on the existing circumstances. -

Results Announcement for the Year Ended December 31, 2020

(GDR under the symbol "HTSC") RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2020 The Board of Huatai Securities Co., Ltd. (the "Company") hereby announces the audited results of the Company and its subsidiaries for the year ended December 31, 2020. This announcement contains the full text of the annual results announcement of the Company for 2020. PUBLICATION OF THE ANNUAL RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT AND THE ANNUAL REPORT This results announcement of the Company will be available on the website of London Stock Exchange (www.londonstockexchange.com), the website of National Storage Mechanism (data.fca.org.uk/#/nsm/nationalstoragemechanism), and the website of the Company (www.htsc.com.cn), respectively. The annual report of the Company for 2020 will be available on the website of London Stock Exchange (www.londonstockexchange.com), the website of the National Storage Mechanism (data.fca.org.uk/#/nsm/nationalstoragemechanism) and the website of the Company in due course on or before April 30, 2021. DEFINITIONS Unless the context otherwise requires, capitalized terms used in this announcement shall have the same meanings as those defined in the section headed “Definitions” in the annual report of the Company for 2020 as set out in this announcement. By order of the Board Zhang Hui Joint Company Secretary Jiangsu, the PRC, March 23, 2021 CONTENTS Important Notice ........................................................... 3 Definitions ............................................................... 6 CEO’s Letter .............................................................. 11 Company Profile ........................................................... 15 Summary of the Company’s Business ........................................... 27 Management Discussion and Analysis and Report of the Board ....................... 40 Major Events.............................................................. 112 Changes in Ordinary Shares and Shareholders .................................... 149 Directors, Supervisors, Senior Management and Staff.............................. -

The Legacy of Tiananmen: 20 Years of Oppression, Activism and Hope Chrd

THE LEGACY OF TIANANMEN: 20 YEARS OF OPPRESSION, ACTIVISM AND HOPE CHRD Chinese Human Rights Defenders (CHRD) Web: Hhttp://crd-net.org/H Email: [email protected] THE LEGACY OF TIANANMEN: 20 YEARS OF OPPRESSION, ACTIVISM AND HOPE Chinese Human Rights Defenders June 1, 2009 Twenty years since the Tiananmen massacre, the Chinese government refuses to accept responsibility, much less apologize or offer compensation, for killing, injuring, imprisoning and persecuting individuals for participating in peaceful protests. The number of the victims, and their names and identities, remain unknown. Families continue to be barred from publicly commemorating and seeking accountability for the death of their loved ones. Activists are persecuted and harassed for independently investigating the crackdown or for calling for a rectification of the government’s verdict on the pro‐democracy movement. Many individuals continue to suffer the consequences of participating in the pro‐democracy movement today. At least eight individuals remain imprisoned in Beijing following unfair trials in which they were convicted of committing “violent crimes”. Those who were released after long sentences have had difficulty re‐integrating into society as they suffer from continued police harassment as well as illnesses and injuries resulting from torture, beatings and mistreatment while in prison. Many of those injured have had to pay for their own medical expenses and continue to struggle as the physical and psychological scars leave them unable to take care of themselves or to work. Some who took part in the protests still find it difficult to make ends meet after they were dismissed from comfortable jobs or expelled from universities after 1989. -

Introduction

Chapter 1 Introduction Life is given to us, we earn it by giving it. Rabindranath Tagore 1.1 UNDERGROUND SPACE AND ITS REQUIREMENT The joy of traveling through underground metros, rail, and road tunnels, espe- cially the half-tunnels in mountains and visiting caves, cannot be described. Modern underground infrastructures are really engineering marvels of the 21st century. The space created below the ground surface is generally known as underground space. Underground space may either be developed by open excavation in soft strata or soil, the top of which is subsequently covered to get the space below, or created by excavation in hard strata or rock. Underground space is available almost everywhere, which may provide the site for activities or infrastructure that are difficult or impossible to install above- ground or whose presence aboveground is unacceptable or undesirable. Another fundamental characteristic of underground space lies in the natural protection it offers to whatever is placed underground. This protection is simultaneously mechanical, thermal, acoustic, and hydraulic (i.e., watertight). It is effective not only in relation to the surface, but also within the underground space itself. Thus underground infrastructure offers great safety against all natural disasters and nuclear wars, ultraviolet rays from holes in the ozone layer, global warm- ing, electromagnetic pollution, and massive solar storms. Increasing population and the developing needs and aspirations of human- kind for our living environment require increasing provision of space of all kinds. This has become a high priority for most “mega cities” since the closing years of the 20th century. The world’s population is becoming more urbanized, at an unprecedented pace. -

Buddhist Print Culture in Early Republican China Gregory Adam Scott Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of

Conversion by the Book: Buddhist Print Culture in Early Republican China Gregory Adam Scott Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Gregory Adam Scott All Rights Reserved This work may be used under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. For more information about that license, see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. For other uses, please contact the author. ABSTRACT Conversion by the Book: Buddhist Print Culture in Early Republican China 經典佛化: 民國初期佛教出版文化 Gregory Adam Scott 史瑞戈 In this dissertation I argue that print culture acted as a catalyst for change among Buddhists in modern China. Through examining major publication institutions, publishing projects, and their managers and contributors from the late nineteenth century to the 1920s, I show that the expansion of the scope and variety of printed works, as well as new the social structures surrounding publishing, substantially impacted the activity of Chinese Buddhists. In doing so I hope to contribute to ongoing discussions of the ‘revival’ of Chinese Buddhism in the modern period, and demonstrate that publishing, propelled by new print technologies and new forms of social organization, was a key field of interaction and communication for religious actors during this era, one that helped make possible the introduction and adoption of new forms of religious thought and practice. 本論文的論點是出版文化在近代中國佛教人物之中,扮演了變化觸媒的角色. 通過研究從十 九世紀末到二十世紀二十年代的主要的出版機構, 種類, 及其主辦人物與提供貢獻者, 論文 說明佛教印刷的多元化 以及範圍的大量擴展, 再加上跟出版有關的社會結構, 對中國佛教 人物的活動都發生了顯著的影響. 此研究顯示在被新印刷技術與新形式的社會結構的推進 下的出版事業, 為該時代的宗教人物展開一種新的相互連結與構通的場域, 因而使新的宗教 思想與實踐的引入成為可能. 此論文試圖對現行關於近代中國佛教的所謂'復興'的討論提出 貢獻. Table of Contents List of Figures and Tables iii Acknowledgements v Abbreviations and Conventions ix Works Cited by Abbreviation x Maps of Principle Locations xi Introduction Print Culture and Religion in Modern China 1. -

A Well-Reasoned Dharma: Buddhist Logic in Republican China

Journal of Chinese Buddhist Studies (2015, 28: 189–234) New Taipei: Chung-Hwa Institute of Buddhist Studies ᷕ厗ἃ⬠⬠⟙䫔Ḵ⋩ℓ㛇ġ 枩 189–234炷㮹⚳ᶨ䘦暞⚃⸜炸炻㕘⊿烉ᷕ厗ἃ⬠䞼䨞 ISSN: 2313-2000 e-ISSN: 2313-2019 A Well-Reasoned Dharma: Buddhist Logic in Republican China Eyal Aviv Assistant Professor, Department of Religion, George Washington University Abstract The rediscovery of Buddhist logic (Skt. hetuvidyƘ, yinming ⚈㖶) in early 20th century China was a key element in the Chinese Buddhist response to modernity. I argue that while Buddhist intellectuals used Buddhist logic for different purposes, their shared goal was to demonstrate that Buddhism was not only modern but also that it was and is indispensable for the modern project. The article addresses two reasons for the renewed interest in Buddhist logic. Firstly, the revival should be understood in the context of logic’s newly gained authority and significance in the early part of the 20th century in China. Secondly, the rise of Buddhist logic was a product of doctrinal debates within Buddhism. With globalization and growing foreign influence, Chinese Buddhists revisited Buddhist teachings that were in the margins for centuries. These teachings, primarily from the Yog¢c¢ra schools, challenged ubiquitous views in Chinese Buddhism. Buddhist logic was not only one of the doctrines that was rediscovered, but it was also one of the most effective tools in debating the nature and future of Buddhism in modern China. Keywords: Buddhist Logic, HetuvidyƘ, YogƘFƘra, Modern Buddhism, Modernity 190 Journal of Chinese Buddhist -

Collection of Articles 论坛文集

COLLECTION OF ARTI论坛文集CLES People to People Exchange Serving Urban Development - keynote speech on 2013 Beijing International Forum on People to People Friendship BPAFFC Executive Vice President Li Xiaoqiang Ladies and gentlemen, friends: Good morning. The theme of 2013 Beijing International Forum on People to People Friendship is" Highlighting Urban Construction by People-to-People Cooperation and Promoting Social Prosperity by Cultural Exchanges." Around this theme, we get together with international friends from five continents, 23 countries, and 76 agencies to join hands, to exchange experiences, to share results, to discuss cooperation, and to seek common development. I would like to take this opportunity to talk about my views about that local friendship association serving the city construction and development. As a mark of mankind’s civilization mileage, the city has already 5,000 years of history in the world. World Urbanization and urban modernization have made a tremendous and far-reaching impact on the economy, society and culture, and have promoted human civilization and progress. However, during the process of urbanization, there have been different kinds of "urban disease”, such as environmental pollution, traffic congestion, population growth, energy shortages, and difficulties in finding jobs. China that is the biggest developing country with the rapid development of urbanization, in the process of urbanization , has also undergone some problems that a number of countries ever had, while at the same time, some new problems of development, like unscientification of urban planning , irrationality of industrial structure, the uneven distribution of educational resources , etc. appeared in China. For this reason, China and the world have been searching constantly for ways and means of solving, researching new problems that may appear in the process of urbanization, and learning experiences and lessons from each other, in order to jointly strive to solve the difficulties and problems during urban construction and development. -

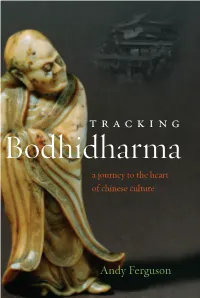

Tracking B Odhidharma

/.0. !.1.22 placing Zen Buddhism within the country’s political landscape, Ferguson presents the Praise for Zen’s Chinese Heritage religion as a counterpoint to other Buddhist sects, a catalyst for some of the most revolu- “ A monumental achievement. This will be central to the reference library B)"34"35%65 , known as the “First Ances- tionary moments in China’s history, and as of Zen students for our generation, and probably for some time after.” tor” of Zen (Chan) brought Zen Buddhism the ancient spiritual core of a country that is —R)9$%: A4:;$! Bodhidharma Tracking from South Asia to China around the year every day becoming more an emblem of the 722 CE, changing the country forever. His modern era. “An indispensable reference. Ferguson has given us an impeccable legendary life lies at the source of China and and very readable translation.”—J)3! D54") L))%4 East Asian’s cultural stream, underpinning the region’s history, legend, and folklore. “Clear and deep, Zen’s Chinese Heritage enriches our understanding Ferguson argues that Bodhidharma’s Zen of Buddhism and Zen.”—J)5! H5<4=5> was more than an important component of China’s cultural “essence,” and that his famous religious movement had immense Excerpt from political importance as well. In Tracking Tracking Bodhidharma Bodhidharma, the author uncovers Bodhi- t r a c k i n g dharma’s ancient trail, recreating it from The local Difang Zhi (historical physical and textual evidence. This nearly records) state that Bodhidharma forgotten path leads Ferguson through established True Victory Temple China’s ancient heart, exposing spiritual here in Tianchang. -

Best Religious Sites in Beijing"

"Best Religious Sites in Beijing" Created by: Cityseeker 5 Locations Bookmarked Niujie Mosque "Ancient Mosque" The design of Niujie mosque, also known as Ox Street Mosque, reflects its locale. It has curved eaves, colorfully painted supports and beams, and glazed roof tiles. It is located on the eastern side of Niu (Ox) Street, home to a large community of Chinese Muslims (known as Hui). The mosque was built under the direction of Nastruddin, the son of an Arabic priest by Smartneddy who came to China in 996! The call to pray is announced from the minaret five times a day, beginning at dawn. The prayer hall can accommodate 1,000. +86 10 6353 2564 88 Niujie, Guang' Anmennei Area, Beijing Temple of Confucius "In Memory of China's Greatest Sage" The Confucius Temple is a beautiful temple with several courtyards and halls. Created during the Yuan Dynasty in 1302, the temple celebrates the philosopher Confucius. There are several myths and stories about the temple, including a tree that can tell when someone is good or bad. The adjoining museum reviews the life of Confucius and how his philosophies by Ivan Walsh influenced the world today as we know it. www.confucius.taichung.gov.tw/ 13 Guozijian Jie, Beijng Yonghe Temple "Historic Temple With Stunning Architecture" Built in 1694, the Yonghe Temple was the residence of Prince Yin Zhen, a son of Emperor Kang Xi of the Qing Dynasty. For many years, it was the leading center for Yellow Hat Shamanism, a distinctive branch of Tibetan Buddhism. It features five large halls and five courtyards with beautifully decorative archways, upturned eaves and carved details. -

2015 Annual Report Annual Report 2015Annual Report

2015 Annual Report Annual ReportAnnual 2015 Contents Important Notice 2 Definitions 5 President’s Statement 8 Company Profile and Key Financial Indicators 10 Summary of the Company’s Business 49 Management Discussion and Analysis and Report of the Board 57 Major Events 139 Changes in Ordinary Shares and Shareholders 180 Preferential Shares 195 Directors, Supervisors, Senior Management and Staff 196 Corporate Governance Report 229 Corporate Bonds 287 Financial Report 296 Index of Documents for Inspection 445 Disclosures 446 2 HUATAI SECURITIES CO., LTD. Important Notice The Board of Directors, the Supervisory Committee, Directors, Supervisors and senior management of the Company undertake that the information in this annual report is true, accurate and complete and contains no false record, misleading statement or material omission, and assume individual and joint liabilities to the information in this report. This report was considered and approved at the twenty-ninth meeting of the third session of the Board of the Company. All Directors of the Company attended the Board meeting. None of the directors and supervisors had objections towards this report. The annual financial report prepared by the Company in accordance with China Accounting Standards for Business Enterprises and the International Financial Reporting Standards was audited by KPMG Huazhen LLP and KMPG respectively, which issued a standard unqualified audit report to the Company. Zhou Yi, officer in charge and officer in charge of accounting of the Company, and Shu Ben’e, officer in charge of the accounting office of the Company (head of accounting department), hereby warrant and guarantee that the financial report contained in the annual report is true, accurate and complete.