Of Ireland: Interim Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sinn-Fein-NA-EES.Pdf

Candidate Name Constituency Amount Assigned Total Expenditure on the candidate by the national agent € € 1. Micheal MacDonncha Dublin Bay North 5000 2.Denise Mitchell Dublin Bay North 5000 3.Chris Andrews Dublin Bay South 5000 450.33 4.Mary Lou McDonald Dublin Central 4000 5.Louise O’Reilly Dublin Fingal 8000 2449.33 6. Eoin O’Broin Dublin Mid West 3000 7. Dessie Ellis Dublin North West 3000 8.Cathleen Carney Boud Dublin North West 5000 9.Sorcha Nic Cormaic Dublin Rathdown 5000 10.Aengus Ó Snodaigh Dublin South 3000 Central 11.Màire Devine Dublin South 3000 Central 12. Sean Crowe Dublin South West 3000 13.Sarah Holland Dublin South West 5000 14.Paul Donnelly Dublin West 3000 69.50 15.Shane O’Brien Dun Laoghaire 5000 73.30 16.Caoimhghìn Ó Caoláin Cavan Monaghan 3000 129.45 17.Kathryn Reilly Cavan Monaghan 3000 192.20 18.Pearse Doherty Donegal 3000 19.Pádraig MacLochlainn Donegal 3000 20.Garry Doherty Donegal 3000 21.Annemarie Roche Galway East 5000 22.Trevor O’Clochartaigh Galway West 5000 73.30 23.Réada Cronin Kildare North 5000 24.Patricia Ryan Kildare South 5000 13.75 25.Brian Stanley Laois 3000 255.55 26.Paul Hogan Longford 5000 Westmeath 27.Gerry Adams Louth 3000 28.Imelda Munster Louth 10000 29.Rose Conway Walsh Mayo 10000 560.57 30.Darren O’Rourke Meath East 6000 31.Peadar Tòibìn Meath West 3000 247.57 32.Carol Nolan Offaly 4000 33.Claire Kerrane Roscommon Galway 5000 34.Martin Kenny Sligo Leitrim 3000 193.36 35.Chris MacManus Sligo Leitrim 5000 36.Kathleen Funchion Carlow Kilkenny 5000 37.Noeleen Moran Clare 5000 794.51 38.Pat Buckley Cork East 6000 202.75 39.Jonathan O’Brien Cork North Central 3000 109.95 40.Thomas Gould Cork North Central 5000 109.95 41.Nigel Dennehy Cork North West 5000 42.Donnchadh Cork South Central 3000 O’Laoghaire 43.Rachel McCarthy Cork south West 5000 101.64 44.Martin Ferris Kerry County 3000 188.62 45.Maurice Quinlivan Limerick City 3000 46.Seamus Browne Limerick City 5000 187.11 47.Seamus Morris Tipperary 6000 1428.49 48.David Cullinane Waterford 3000 565.94 49.Johnny Mythen Wexford 10000 50.John Brady Wicklow 5000 . -

“Éire Go Brách” the Development of Irish Republican Nationalism in the 20Th Into the 21St Centuries

“Éire go Brách” The Development of Irish Republican Nationalism in the 20th into the 21st Centuries Alexandra Watson Honors Thesis Dr. Giacomo Gambino Department of Political Science Spring 2020 Watson 2 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Literature Review: Irish Nationalism -- What is it ? 5 A Brief History 18 ‘The Irish Question’ and Early Roots of Irish Republicanism 20 Irish Republicanism and the War for Independence 25 The Anglo Irish Treaty of 1921, Pro-Treaty Republicanism vs. Anti-Treaty Republicanism, and Civil War 27 Early Statehood 32 ‘The Troubles’ and the Good Friday Agreement 36 Why is ‘the North’ Different? 36 ‘The Troubles’ 38 The Good Friday Agreement 40 Contemporary Irish Politics: Irish Nationalism Now? 45 Explaining the Current Political System 45 Competing nationalisms Since the Good Friday Agreement and the Possibility of Unification 46 2020 General Election 47 Conclusions 51 Appendix 54 Acknowledgements 57 Bibliography 58 Watson 3 Introduction In June of 2016, the people of the United Kingdom democratically elected to leave the European Union. The UK’s decision to divorce from the European Union has brought significant uncertainty for the country both in domestic and foreign policy and has spurred a national identity crisis across the United Kingdom. The Brexit negotiations themselves, and the consequences of them, put tremendous pressure on already strained international relationships between the UK and other European countries, most notably their geographic neighbour: the Republic of Ireland. The Anglo-Irish relationship is characterized by centuries of mutual antagonism and the development of Irish national consciousness, which ultimately resulted in the establishment of an autonomous Irish free state in 1922. -

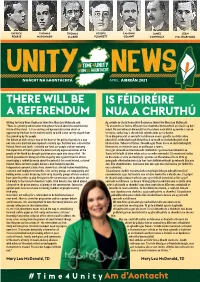

April Unity News

PATRICK THOMAS THOMAS JOSEPH ÉAMONN JAMES SEÁN PEARSE McDONAGH CLARKE PLUNKETT CEANNT CONNOLLY Mac DIARMADA #Time4Unity UNITY# AM LE hAONTACHT NEWS NUACHT NA hAONTACHTA APRIL AIBREÁN 2021 THERE WILL BE IS FÉIDIRÉIRE AWriting forREFERENDUM Unity News Úachtaran Shinn Féin Mary Lou McDonald said: AgNUA scríobh do Unity News A dúirt ÚachtaranCHRUTHÚ Shinn Féin Mary Lou McDonald: “There is a growing conversation throughout Ireland about the constitutional “Tá an comhrá ar fud na hÉireann faoi thodhchaí bunreachtúil an oileáin ag dul i future of the island. It is an exciting and dynamic discussion about an méad. Plé corraitheach dinimiciúil atá faoi dheis nach bhfuil ag mórán i saol an opportunity few have in the modern world; to build a new society shaped from lae inniu; sochaí nua a chruthú ón talamh aníos ag na daoine. the ground up by the people. Tá an díospóireacht ar aontacht na hÉireann anois i gcroílár an chláir oibre The debate on Irish unity is now at the heart of the political agenda in a way pholaitiúil ar bhealach nach bhfacthas ó cuireadh an chríochdheighilt céad not seen since partition was imposed a century ago. Partition was a disaster for bliain ó shin. Tubaiste d’Éirinn, Thuaidh agus Theas ba ea an chríochdheighilt. Ireland, North and South. It divided our land, our people and our economy. Rinnean tír, an mhuintir agus an geilleagar a roinnt. The imposition of Brexit against the democratically expressed wishes of the Toisc gur cuireadh an Breatimeacht i bhfeidhm i gcoinne thoil mhuintir an people of the North has brought partition once again into sharp relief. -

Copyrighted Material

Index Note: page numbers in italics denote illustrations or maps Abbey Theatre 175 sovereignty 390 Abbot, Charles 28 as Taoiseach 388–9 abdication crisis 292 and Trimble 379, 409, 414 Aberdeen, Earl of 90 Aiken, Frank abortion debate 404 ceasefire 268–9 Academical Institutions (Ireland) Act 52 foreign policy 318–19 Adams, Gerry and Lemass 313 assassination attempt 396 and Lynch 325 and Collins 425 and McGilligan 304–5 elected 392 neutrality 299 and Hume 387–8, 392, 402–3, 407 reunification 298 and Lynch 425 WWII 349 and Paisley 421 air raids, Belfast 348, 349–50 St Andrews Agreement 421 aircraft industry 347 on Trimble 418 Aldous, Richard 414 Adams, W.F. 82 Alexandra, Queen 174 Aer Lingus 288 Aliens Act 292 Afghan War 114 All for Ireland League 157 Agar-Robartes, T.G. 163 Allen, Kieran 308–9, 313 Agence GénéraleCOPYRIGHTED pour la Défense de la Alliance MATERIAL Party 370, 416 Liberté Religieuse 57 All-Ireland Committee 147, 148 Agricultural Credit Act 280 Allister, Jim 422 agricultural exports 316 Alter, Peter 57 agricultural growth 323 American Civil War 93, 97–8 Agriculture and Technical Instruction, American note affair 300 Dept of 147 American War of Independence 93 Ahern, Bertie 413 Amnesty Association 95, 104–5, 108–9 and Paisley 419–20 Andrews, John 349, 350–1 resignation 412–13, 415 Anglesey, Marquis of 34 separated from wife 424 Anglicanism 4, 65–6, 169 Index 513 Anglo-American war 93 Ashbourne Purchase Act 133, 150 Anglo-Irish Agreement (1938) 294, 295–6 Ashe, Thomas 203 Anglo-Irish Agreement (1985) Ashtown ambush 246 aftermath -

A Fresh Start? the Northern Ireland Assembly Election 2016

A fresh start? The Northern Ireland Assembly election 2016 Matthews, N., & Pow, J. (2017). A fresh start? The Northern Ireland Assembly election 2016. Irish Political Studies, 32(2), 311-326. https://doi.org/10.1080/07907184.2016.1255202 Published in: Irish Political Studies Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights Copyright 2016 Taylor & Francis. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:30. Sep. 2021 A fresh start? The Northern Ireland Assembly election 2016 NEIL MATTHEWS1 & JAMES POW2 Paper prepared for Irish Political Studies Date accepted: 20 October 2016 1 School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK. Correspondence address: School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies, University of Bristol, 11 Priory Road, Bristol BS8 1TU, UK. -

The Corporate Governance of Agencies in Ireland Non

CorporateGovernanceAgencies-Prelims.qxd 22/11/2005 17:32 Page 1 The Corporate Governance of Agencies in Ireland Non-commercial National Agencies CorporateGovernanceAgencies-Prelims.qxd 22/11/2005 17:32 Page 2 CorporateGovernanceAgencies-Prelims.qxd 22/11/2005 17:32 Page 3 CPMR Research Report 6 The Corporate Governance of Agencies in Ireland Non-commercial National Agencies Anne-Marie McGauran Koen Verhoest Peter C. Humphreys CorporateGovernanceAgencies-Prelims.qxd 22/11/2005 17:32 Page 4 First published in 2005 by the Institute of Public Administration 57-61 Lansdowne Road Dublin 4 Ireland in association with The Committee for Public Management Research www.ipa.ie © 2005 with the Institute of Public Administration All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 1-904541-30-5 ISSN 1393-9424 Cover design by M&J Graphics, Dublin Typeset by the Institute of Public Administration Printed by BetaPrint, Dublin CorporateGovernanceAgencies-Prelims.qxd 22/11/2005 17:32 Page 5 CONTENTS Acknowledgements ix About the Authors x Executive Summary xi Chapter 1: Introduction 1 1.1 Setting the scene 1 1.2 Structure of the report 2 Chapter 2: Agencies - what and why? 4 2.1 What are agencies? 4 2.2 Agencies: why? -

Rt Hon Rishi Sunak MP Chancellor of the Exchequer HM Treasury 1 Horse Guards Road London SW1A 2HQ

Rt Hon Rishi Sunak MP Chancellor of the Exchequer HM Treasury 1 Horse Guards Road London SW1A 2HQ Dear Chancellor, Budget Measures to Support Hospitality and Tourism We are writing today as members and supporters of the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Hospitality and Tourism ahead of the Budget on 3rd March. As you will of course be aware, hospitality and tourism are vital to the UK’s economy along with the livelihoods and wellbeing of millions of people across the UK. The pandemic has amplified this, with its impacts illustrating the pan-UK nature of these sectors, the economic benefits they generate, and the wider social and wellbeing benefits that they provide. The role that these sectors play in terms of boosting local, civic pride in all our constituencies, and the strong sense of community that they foster, should not be underestimated. It is well-established that people relate to their local town centres, high streets and community hubs, of which the hospitality and tourism sectors are an essential part. The latest figures from 2020 highlight the significant impact that the virus has had on these industries. In 2020, the hospitality sector has seen a sales drop of 53.8%, equating to a loss in revenue of £72 billion. This decline has impacted the UK’s national economy by taking off around 2 percentage points from total GDP. For hospitality, this downturn is already estimated to be over 10 times worse than the impact of the financial crisis. It is estimated that employment in the sector has dropped by over 1 million jobs. -

Minimum Wages and the Gender Gap in Pay: New Evidence from the UK and Ireland

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 11502 Minimum Wages and the Gender Gap in Pay: New Evidence from the UK and Ireland Olivier Bargain Karina Doorley Philippe Van Kerm APRIL 2018 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 11502 Minimum Wages and the Gender Gap in Pay: New Evidence from the UK and Ireland Olivier Bargain Bordeaux University and IZA Karina Doorley ESRI and IZA Philippe Van Kerm University of Luxembourg and LISER APRIL 2018 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but IZA takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The IZA Institute of Labor Economics is an independent economic research institute that conducts research in labor economics and offers evidence-based policy advice on labor market issues. Supported by the Deutsche Post Foundation, IZA runs the world’s largest network of economists, whose research aims to provide answers to the global labor market challenges of our time. Our key objective is to build bridges between academic research, policymakers and society. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Schaumburg-Lippe-Straße 5–9 Phone: +49-228-3894-0 53113 Bonn, Germany Email: [email protected] www.iza.org IZA DP No. 11502 APRIL 2018 ABSTRACT Minimum Wages and the Gender Gap in Pay: New Evidence from the UK and Ireland Women are disproportionately in low paid work compared to men so, in the absence of rationing effects on their employment, they should benefit the most from minimum wage policies. -

1. Debbie Abrahams, Labour Party, United Kingdom 2

1. Debbie Abrahams, Labour Party, United Kingdom 2. Malik Ben Achour, PS, Belgium 3. Tina Acketoft, Liberal Party, Sweden 4. Senator Fatima Ahallouch, PS, Belgium 5. Lord Nazir Ahmed, Non-affiliated, United Kingdom 6. Senator Alberto Airola, M5S, Italy 7. Hussein al-Taee, Social Democratic Party, Finland 8. Éric Alauzet, La République en Marche, France 9. Patricia Blanquer Alcaraz, Socialist Party, Spain 10. Lord John Alderdice, Liberal Democrats, United Kingdom 11. Felipe Jesús Sicilia Alférez, Socialist Party, Spain 12. Senator Alessandro Alfieri, PD, Italy 13. François Alfonsi, Greens/EFA, European Parliament (France) 14. Amira Mohamed Ali, Chairperson of the Parliamentary Group, Die Linke, Germany 15. Rushanara Ali, Labour Party, United Kingdom 16. Tahir Ali, Labour Party, United Kingdom 17. Mahir Alkaya, Spokesperson for Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation, Socialist Party, the Netherlands 18. Senator Josefina Bueno Alonso, Socialist Party, Spain 19. Lord David Alton of Liverpool, Crossbench, United Kingdom 20. Patxi López Álvarez, Socialist Party, Spain 21. Nacho Sánchez Amor, S&D, European Parliament (Spain) 22. Luise Amtsberg, Green Party, Germany 23. Senator Bert Anciaux, sp.a, Belgium 24. Rt Hon Michael Ancram, the Marquess of Lothian, Former Chairman of the Conservative Party, Conservative Party, United Kingdom 25. Karin Andersen, Socialist Left Party, Norway 26. Kirsten Normann Andersen, Socialist People’s Party (SF), Denmark 27. Theresa Berg Andersen, Socialist People’s Party (SF), Denmark 28. Rasmus Andresen, Greens/EFA, European Parliament (Germany) 29. Lord David Anderson of Ipswich QC, Crossbench, United Kingdom 30. Barry Andrews, Renew Europe, European Parliament (Ireland) 31. Chris Andrews, Sinn Féin, Ireland 32. Eric Andrieu, S&D, European Parliament (France) 33. -

Lisnaskea (Updated May 2021)

Branch Closure Impact Assessment Closing branch: Lisnaskea 141 Main Street Lisnaskea BT92 0JE Closure date: 07/07/2021 The branch your account(s) will be administered from: Enniskillen Information correct as at: February 2021 1 What’s in this brochure The world of banking is changing and so are we Page 3 How we made the decision to close this branch What will this mean for our customers? Customers who need more support Access to Banking Standard (updated May 2021) Bank safely – Security information How to contact us Branch information Page 6 Lisnaskea branch facilities Lisnaskea customer profile (updated May 2021) How Lisnaskea customers are banking with us Page 7 Ways for customers to do their everyday banking Page 8 Other Bank of Ireland branches (updated May 2021) Bank of Ireland branches that will remain open Nearest Post Office Other local banks Nearest free-to-use cash machines Broadband available close to this branch Other ways for customers to do their everyday banking Definition of key terms Page 11 Customer and Stakeholder feedback Page 12 Communicating this change to customers Engaging with the local community What we have done to make the change easier 2 The world of banking is changing and so are we Bank of Ireland customers in Northern Ireland have been steadily moving to digital banking over the past 10 years. The pace of this change is increasing. Since 2017, for example, digital banking has increased by 50% while visits to our branches have sharply declined. Increasingly, our customers are using Post Office services with 52% of over-the-counter transactions now made in Post Office branches. -

The European Community and the Relationships Between Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic: a Test of Neo-Functionalism

Tresspassing on Borders? The European Community and the Relationships between Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic: A Test of Neo-functionalism Etain Tannam Department of Government London School of Economics and Political Science Ph.D. thesis UMI Number: U062758 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U062758 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 or * tawmjn 7/atA K<2lt&8f4&o ii Contents List of Figures v Acknowledgements vi 1. The European Community and the Irish/Northern Irish Cross- 1 border Relationship: Theoretical Framework Introduction 2 1. The Irish/Northern Irish Cross-border Relationship: A Critical 5 Test of Neo-functionalism ii. Co-operation and The Northern Irish/Irish Cross-Border 15 Relationship iii. The Irish/Northern Irish Cross-border Relationship and the 21 Anglo-Irish Agreement iv. The Anglo-Irish Agreement and International Relations Theory 25 Conclusion: The Irish Cross-border Relationship and International 30 Relations Theory: Hypotheses 2. A History ofThe Cross-Border Political Relationship 34 Introduction 35 i. Partition and the Boundary Commission. -

Paul's Text – with Edits from Jane

Reuters Institute Digital News Report (Ireland) 2018 REUTERS INSTITUTE for the STUDY of JOURNALISM Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2018 (Ireland) Eileen Culloty, Kevin Cunningham, Jane Suiter, and Paul McNamara Contents BAI Foreword 4 DCU FuJo Foreword 5 Methodology 6 Authorship 7 Executive Summary 8 Section One: Irish News Consumers 9 Section Two: Attitudes and Preferences 23 Section Three: Sources, Brands, and Engagement 37 Comment: “Fake News” and Digital Literacy by Dr Eileen Culloty 53. Comment: Trust in News by Dr Jane Suiter 55. Comment: The Popularity of Podcasts by Dr David Robbins 57. Digital News Report Ireland 2018 – DCU FuJo & Broadcasting Authority of Ireland 3 BAI Foreword Promoting a plurality of voices, viewpoints outlets and sources in Irish media is a key element of the BAI’s mission as set out in the Strategy Statement 2017-2019. Fostering media plurality remains a central focus for media regulators across Europe as we adapt to meet the challenges of a rapidly evolving media landscape. In such an environment, timely, credible relevant data is essential to facilitate an informed debate and evidence-based decision making. Since it was first published in 2015, the Reuters Institute Digital News Report for Ireland has established itself as an invaluable source of current consumption and impact data in relation to news services in Ireland. As such, it has supported a more comprehensive understanding of, and debate about, the current position and evolving trends in media plurality. Each year the BAI, with its partners in DCU and Reuters, aims to provide a comprehensive picture of the current news environment through this Report.