I to BE SEEN and ALSO HEARD: TOWARD a MORE TRULY PUBLIC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biographical Description for the Historymakers® Video Oral History with Ethel Darden

Biographical Description for The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History with Ethel Darden PERSON Darden, Ethel, 1900-2011 Alternative Names: Ethel Darden; Life Dates: February 17, 1900-July 17, 2011 Place of Birth: Dallas, Texas, USA Residence: Chicago, Illinois Occupations: Elementary School Teacher Biographical Note Educator Ethel Darden was born Ethel Roby Boswell on February 17, 1900 in Dallas, Texas. She and her twin sister, Esther, were the youngest of the five daughters of two school teachers, Ella Mary Allen and Charles Roby Boswell, from Talladega, Alabama. In 1890, her parents moved to Dallas, Texas and by the turn of century had three daughters: Alberta, Bessie and Doris. Darden attended Washington Elementary School (School #2) and graduated from Dallas Colored High School in 1917. The twins attended historically black Wiley College, in Marshall, Texas and Darden High School in 1917. The twins attended historically black Wiley College, in Marshall, Texas and Darden graduated in 1921. Teaching school in Dallas for nearly two decades, she married Lloyd Darden, a successful accountant in 1942 and moved with him to Chicago where her sister, Doris Allen enlisted her as a teacher in Howalton Day School, where she was a founder. An outgrowth of Oneida Cockrell's pioneering pre-school and kindergarten, the Howalton Day School (1947-1986) was founded by three black educators: June Howe- White, Doris Allen-Anderson, and Charlotte B. Stratton. The name of the school is from a combination of the founders' three last names. Chicago's oldest African American, private, non-sectarian school, Howalton's educational philosophy stressed discovery, enthusiasm, creativity, the arts and the humanities in an informal, controlled atmosphere. -

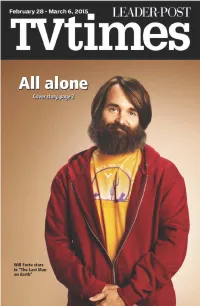

One and Only

Cover Story One and only Fox tackles the loneliest number in ‘The Last Man on Earth’ By Cassie Dresch people after a virus takes out him get into a lot of really silly TV Media all of Earth’s population. His shenanigans. family is gone, his coworkers “It’s all just kind of stupid ello? Hi? Anybody out are gone, the president is gone. stuff that I go around and do,” Hthere? Of course there is, Everyone. Gone. he said in an interview with otherwise life would be very, So what does he do? He “Entertainment Weekly.” very, very lonely. Fox is taking a travels the United States doing “That’s been one of the most stab at the ultimate life of lone- things he never would have fun parts of the job. About once liness in the new half-hour been able to do otherwise — a week I get to do something comedy “The Last Man on sing the national anthem at that seems like it’d be amaz- Earth,” premiering Sunday, Dodger Stadium, smear gooey ingly fun to do: shoot a flame March 1. peanut butter all over a price- thrower at a bunch of wigs, The premise around “Last less piece of art ... then walk have a steamroller steamroll Man” is a simple one, albeit a away with it, break things. The over a case of beer. Just dumb little strange. An average, un- show, according to creator and stuff like that, which pretty assuming man is on the hunt star Will Forte (“Saturday Night much is all it takes to make me for any signs of other living Live,” “Nebraska,” 2013), sees happy.” Registration $25.00 online: www.skseniorsmechanism.ca or phone 306-359-9956 2 Cover Story Flame throwers and steam- ally proud of what has come rollers? Again, it’s a strange out of it so far.” concept, but Fox is really be- Of course, you have to won- Index hind the show. -

Jewish Federation of Metropolitan Chicago 2018 ANNUAL REPORT OUR YEAR in REVIEW

Jewish Federation of Metropolitan Chicago 2018 ANNUAL REPORT OUR YEAR IN REVIEW The Jewish United Fund/Jewish Federation of Metropolitan Chicago amplifies our collective strength to make the world a better place—for everyone. Community powered, we consider the totality of local and global Jewish needs and how to address them. From generation to generation, we help people connect to Jewish life and values, fueling a dynamic, enduring community that comes together for good. Chicago’s Jewish community runs on the passion, gen- • $87,672,775 allocated to charitable ventures world- erosity and commitment of its members. Together, we wide in partnership with our Donor Advised Funds lifted the 2017 Jewish United Fund Annual Campaign and Supporting Foundations. to a record $86.97 million to support the Jewish United Fund/Jewish Federation of Metropolitan Chicago’s vital With these funds, we helped sustain Jewish life and network of agency partners. The $2.6 million increase Jewish lives, identifying and addressing the complex over the 2016 Annual Campaign made it possible to needs of our Jewish community in Chicago, in Israel care for additional Holocaust survivors, people with and worldwide. disabilities and other vulnerable community members; to more effectively fight anti-Semitism and hate; and to engage more people in Jewish life and learning. The JUF Annual Campaign is the foundational com- munity component of JUF/Federation’s multi-faceted financial resource development efforts, which secured $379,411,478 in total revenue in FY2018. In addition to donations from individuals and corporate partners, this total includes grants from foundations, the government and United Way, plus distributions from Donor Advised Funds and Supporting Foundations. -

Beach Sentenced to 35 Years in Prison for Murder Arrest the Day After the Incident

FRONT PAGE A1 TOOELETRANSCRIPT Tooele boys bag SERVING third soccer win TOOELE COUNTY this season SINCE 1894 See A9 BULLETIN TUESDAY March 1010,, 2015 www.TooeleOnline.com Vol. 121 No. 81 $1.00 Beach sentenced to 35 years in prison for murder arrest the day after the incident. San Antonio man convicted of manslaughter, obstruction of justice in April stabbing Beach had pleaded not guilty to both charges in a preliminary hear- by Steve Howe State Prison. convicted in 3rd District Court on second-degree felony, the obstruc- ing in October. STAFF WRITER Larry Beach, 20, accepted a plea Tuesday morning of manslaughter tion of justice charge carries a term Horowitz, a Stansbury High deal with the state on Jan. 13 to and obstruction of justice — terms of one to 15 years. School senior, was killed on April 26 A San Antonio man who pleaded plead guilty to first-degree mur- he will serve consecutively. The time Beach spent in the during a midnight fight on the play- guilty for the stabbing death of 17- der and second-degree obstruc- The manslaughter charge includ- Tooele County Detention Center ground at Stansbury Elementary year-old Jesse Horowitz was sen- tion of justice, both felonies. Under ed a deadly weapons enhancement, will count toward Beach’s sentence. tenced to up to 35 years in Utah the terms of the deal, Beach was for a term of two to 20 years. As a Beach has been in custody since his SEE BEACH PAGE A7 ➤ Larry Beach Teacher rally fills Capitol rotunda by Tim Gillie the rotunda in support of the STAFF WRITER Legislature fully funding the governor’s proposed increase in Tooele educators and parents basic education spending. -

The Chatterbox Press Release V6 Rev100815

Contact: Lindsey Horvitz WNET 212-560-6609 [email protected] Atiya Frederick PBS 703-739-5147 [email protected] Chelsey Saatkamp Goodman Media International 212-576-2700 [email protected] Press Materials: thirteen.org/pressroom Website: http://to.pbs.org/thechatterbox Facebook: ChatterBoxPBS / ThirteenWNET /PBS Digital Studios Twitter: @ChatterBoxPBS /@ThirteenWNET / @PBSDS New Original Web Series from WNET and PBS Digital Studios Explores the Worlds of Tech and Pop Culture The ChatterBox , hosted by intergenerational duo Kevin and Grandma Lill Droniak , to premiere new episodes weekly beginning October 8, 2015 Preview the series in the newly released trailer at http://to.pbs.org/thechatterbox WNET , New York’s flagship PBS station, and PBS Digital Studios have announced the launch of The ChatterBox with Kevin and Grandma Lill, an original digital series exploring the worlds of tech and pop culture. The series, the second to result from the previously announced strategic partnership between WNET’s Interactive Engagement Group and PBS Digital Studios, will debut on a new channel within the PBS Digital Studios YouTube network on Thursday, October 8, 2015, and will release a new episode every week. Featuring the hilarious intergenerational duo of 18-year-old Kevin Droniak and his Grandma Lill as they test the newest gadgets and games and they comment on the latest pop culture trends, The ChatterBox will bridge the generational—and technological—gap through the shared experience of discovery. The series – which combines practical information with quirky humor – will launch with topics including Dubsmash, unboxing videos, slang and gifs, and will feature conversations with guest experts including Vanessa Hill from the PBS Digital Studios series “BrainCraft”; Mashable illustrator Bob Al-Greene; CNET editor Dan Ackerman; “Ask Amy” advice columnist Amy Dickenson; “The Score” senior reporter Rod “Slasher” Breslau; Engadget senior editor Nicole Lee; Flama video creator, writer and producer Joanna Hausmann and others. -

The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons Film Studies (MA) Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-2021 The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood Michael Chian Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/film_studies_theses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Chian, Michael. "The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood." Master's thesis, Chapman University, 2021. https://doi.org/10.36837/chapman.000269 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Film Studies (MA) Theses by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood A Thesis by Michael Chian Chapman University Orange, CA Dodge College of Film and Media Arts Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Film Studies May, 2021 Committee in charge: Emily Carman, Ph.D., Chair Nam Lee, Ph.D. Federico Paccihoni, Ph.D. The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood Copyright © 2021 by Michael Chian III ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my advisor and thesis chair, Dr. Emily Carman, for both overseeing and advising me throughout the development of my thesis. Her guidance helped me to both formulate better arguments and hone my skills as a writer and academic. I would next like to thank my first reader, Dr. Nam Lee, who helped teach me the proper steps in conducting research and recognize areas of my thesis to improve or emphasize. -

Tvtimes Are Calling Every Day Is Exceptional at Meadowood Call 812-336-7060 to Tour

-711663-1 HT AndyMohrHonda.com AndyMohrHyundai.com S. LIBERTY DRIVE BLOOMINGTON, IN THE HERALD-TIMES | THE TIMES-MAIL | THE REPORTER-TIMES | THE MOORESVILLE-DECATUR TIMES August 3 - 9, 2019 NEW ADVENTURES TVTIMES ARE CALLING EVERY DAY IS EXCEPTIONAL AT MEADOWOOD CALL 812-336-7060 TO TOUR. -577036-1 HT 2455 N. Tamarack Trail • Bloomington, IN 47408 812-336-7060 www.MeadowoodRetirement.com 2019 Pet ©2019 Five Star Senior Living Friendly Downsizing? CALL THE RESULTS TEAM Brokered by: | Call Jenivee 317-258-0995 or Lesaesa 812-360-3863 FREE DOWNSIZING Solving Medical Mysteries GUIDE “Flip or Flop” star and former cancer patient Tarek El -577307-1 Moussa is living proof behind the power of medical HT crowdsourcing – part of the focus of “Chasing the Cure,” a weekly live broadcast and 24/7 global digital platform, premiering Thursday at 9 p.m. on TNT and TBS. Senior Real Estate Specialist JENIVEE SCHOENHEIT LESA OLDHAM MILLER Expires 9/30/2019 (812) 214-4582 HT-698136-1 2019 T2 | THE TV TIMES| The Unacknowledged ‘Mother of Modern Dish Communications’ Bedford DirecTV Cable Mitchell Comcast Comcast Comcast New Wave New New Wave New Mooreville Indianapolis Indianapolis Bloomington Conversion Martinsviolle BY DAN RICE television for Lionsgate. “It is one of those rare initiatives that WTWO NBC E@ - - - - - - - With the availability, cost E# seeks to inspire with a larger S WAVE NBC - 3 - - - - - and quality of healthcare being $ A WTTV CBS E 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 humanitarian purpose, and T such hot-button issues these E^ WRTV ABC 6 6 6 6 - 6 6 URDAY, -

The Hidden Persuaders

VANCE PACKARD THE HIDDEN PERSUADERS LONGMANS, GREEN & CO LONDON • NEW YORK • TORONTO LONGMANS, GREEN AND CO LTD 6 & 7 CLIFFORD STREET LONDON W I THIBAULT HOUSE THIBAULT SQUARE CAPE TOWN 605-611 LONSDALE STREET MELBOURNE LONGMANS, GREEN AND CO INC 55 FIFTH AVENUE NEW YORK 3 LONGMANS, GREEN AND CO 20 CRANFIELD ROAD TORONTO 16 ORIENT LONGMANS PRIVATE LTD CALCUTTA BOMBAY MADRAS DELHI HYDERABAD DACCA This edition first published 1957 Second impression 1957 Printed in Great Britain by Lowe & Brydone (Printers) Ltd., London, N.W.10 To Virginia Contents CHAPTER 1. THE DEPTH APPROACH PERSUADING US AS CONSUMERS 2. THE TROUBLE WITH PEOPLE 3. So AD MEN BECOME DEPTH MEN 4. AND THE HOOKS ARE LOWERED 5. SELF-IMAGES FOR EVERYBODY 6. Rx FOR OUR SECRET DISTRESSES 7. MARKETING EIGHT HIDDEN NEEDS 8. THE BUILT-IN SEXUAL OVERTONE 9. BACK TO THE BREAST, AND BEYOND 10. BABES IN CONSUMERLAND 11. CLASS AND CASTE IN THE SALESROOM 12. SELLING SYMBOLS TO UPWARD STRIVERS 13. CURES FOR OUR HIDDEN AVERSIONS 14. COPING WITH OUR PESKY INNER EAR 15. THE PSYCHO-SEDUCTION OF CHILDREN 16. NEW FRONTIERS FOR RECRUITING CUSTOMERS PERSUADING US AS CITIZENS 17. POLITICS AND THE IMAGE BUILDERS 18. MOLDING "TEAM PLAYERS" FOR FREE ENTERPRISE 19. THE ENGINEERED YES 20. CARE AND FEEDING OF POSITIVE THINKERS 21. THE PACKAGED SOUL? IN RETROSPECT 22. THE QUESTION OF VALIDITY 23. THE QUESTION OF MORALITY INDEX TO BRITISH READERS WHILE some of the research for this book came from British sources it was gathered predominantly in the United States because that is where I happen to live and also because that is where manipulation of the public has taken hold most firmly. -

Sample Download

When Cloughie Sounded Off in tvtimes Graham Denton Contents Introduction 10 Me and My Big Mouth 18 Sir Alf Please Note: Wednesday’s No Night for Virgins 33 Carry On Fighting, Ali … We Can’t Do without You 42 Why I’d Like to Sign Nureyev 53 Why I Wish I’d Taken That Job in Barcelona 56 I’d Love to See a Soccer Riot in the Studio 64 Show the World We’re Still Champs 72 Where Have All the Goalscorers Gone? 78 Tell Me What’s Wrong with Football 81 Born to Take Over As Number One 84 My Four Ways to Make Brighton Rock 95 Let’s Make ’74 Champagne Year 103 Mighty Mick, My Player of the Year 113 Clough Asked and You Told Him … Soccer Violence? Blame the Players 121 We’ll Succeed Because We’re the Best 125 You Should Never Miss a Penalty 128 Finished at 30? Don’t You Believe It … 140 The Guilty Men of TV Soccer 154 Don Revie … My Man for All Seasons 157 Let’s Have a Soccer University 167 Five-a-Side … A Natural Break from the Most Insane Season in the World 170 It’s Liverpool for the Cup 178 Never Mind Munich, It’s Haggis and Hampden That Count 185 Alf Had a Good Innings – Now Let’s Get On with Winning in ’78 196 What Does Happen to the Likely Lads of Football? 204 Join ITV for the Big Football Lock-In 216 Did You Say It’s Only a Game? 224 The Clown v the Genius 232 Stop the Bickering – That’s How to Win in ’78 240 New Boys? I’m Backing Jackie to Last 249 The Man Who Wins by Keeping Quiet 262 Mick Channon is My Player of the Month: He’s Skilful, Aggressive, Competitive – and His Loyalty is Priceless 274 Player’s Lib? I’m All for It 286 All Football’s -

Good Things Come in Threes. the Third Season of Experience Michiana Kicks Off This Month

Pl a nner Michiana’s bi-monthly Guide to WNIT Public Television Issue No. 2 March — April 2014 Good things come in threes. The third season of experience michiana kicks off this month. Board of Directors Chair Ida Reynolds Watson Vice Chair Rodney F. Ganey, Ph.D. A Message from Greg Giczi Kevin Morrison President and GM, WNIT Public Television Susan Ohmer, Ph.D. President and General Manager Greg Giczi Treasurer Is it safe to say that spring is around the corner? Thomas E. Slager I’ve had enough snow and cold this winter. I’m ready for some warmer weather! Secretary Cari Shein There was some positive value to WNIT when the weather was so bad … everyone stayed at home and Directors was watching television. We received all sorts of indications that viewership was up. Downton Abbey Thomas G. Coley, Ph.D. Season 4 set viewership records on its premiere night. We all know that the Super Bowl was the most Marvin Curtis watched program that night, but can you guess what the second most watched program happened to Katy Demarais be? It was Downton Abbey. You WNIT viewers are classy people and it is catching on! Robert G. Douglass Irene E. Eskridge 2014 marks WNIT’s 40th year. The amount of technology changes during that period is boggling, David M. Findlay and it will be hard to predict what may happen in our next 40 years, so I’m just focusing on how we William A. Gitlin will need to prepare for the next five or so to the year 2020. -

The Hajny Mammoths: Age Profiles and Species Peggy Flynn

Interdisciplinary Studies of the Hajny Mammoth Site, Dewey County, Oklahoma by Don G. Wyckoff Brian J. Carter Peggy Flynn Larry D. Martin Branley A. Branson and James L. Theler Studies of Oklahoma's Past No. 17 Oklahoma Archeological Survey University of Oklahoma Norman, Oklahoma February 1992 Interdisciplinary Studies of the Hajny Mammoth Site, Dewey County, Oklahoma Don G. Wyckoff Oklahoma Archeological Survey University of Oklahoma Nonnan, Oklahoma Brian J. Carter Department ofAgronomy Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma Peggy Flynn Edmond, Oklahoma Larry D. Martin Kansas Museum of Natural History University of Kansas Lawrence, Kansas Branley A. Branson College of Natural and Mathematical Sciences Eastern Kentucky University Richmond, Kentucky James L. Theler Department of Sociology/Anthropology University of Wisconsin-LaCrosse LaCrosse, Wisconsin and Special Art Work by Irene Johnson Comanche, Oklahoma Studies of Oklahoma's Past No. 17 Oklahoma Archeological Survey University of Oklahoma Norman, Oklahoma February 1992 To order a copy of this volume, please send $15.00 plus $2.00 for postage and handling for the first copy. The postage for each additional copy is $0.50. Publisher's address: Oklahoma Archeological Survey 1808 Newton Drive, Room 116 Norman, OK 73019-0540 ISBN: 1-881346-00-5 ©1992 by Oklahoma Archeological Survey Norman, Oklahoma 73019-0540 Printed in the United States of America -ii- THE PRODUCTION AND PUBLICATION OF THE COLOR PLATES HEREIN WERE MADE POSSIBLE BY THE GENEROUS DONATIONS OF: Mr. R.W. Bellamy (Vian, OK) Dr. Jim Cox (Newcastle, OK) Mr. Wendel Hajny (Oakwood, OK) Mr. C.B. Hannum (Ardmore, OK) Ms. Adrienne Huey (Oklahoma City, OK) Mr. -

Michiana's Rising Star

Pl a nnerMichiana’s bi-monthly Guide to WNIT Public Television Issue No. 4 July — August 2015 Michiana’s Rising Star Vote for your favorites on Thursdays in July and tune in August 2–7 to see who will be crowned as the next Michiana’s Rising Star A Message from Greg Giczi Board of President and GM, WNIT Public Television Directors Chairman Ida Reynolds Watson Vice Chair Rodney F. Ganey, Ph.D. Susan Ohmer, Ph.D. President and Dear Supporters of Public Television: General Manager Greg Giczi I’m pumped up! I was able to attend the PBS annual meeting in May. It’s an opportunity for Treasurer general managers from public television stations from all over the country to share ideas and learn Thomas E. Slager about PBS’s upcoming plans. Unlike all the other television and cable networks, PBS is not a Secretary “network” but rather a programming cooperative owned by its member stations. Just like WNIT Cari Shein belongs to you, all of PBS belongs to you too! Directors David L. Bankoff, MD Paula Kerger, president of PBS, recently celebrated a work anniversary, she is now the longest Thomas G. Coley, Ph.D. Marvin Curtis serving president in PBS’s history. She has done a terrific job leading our organization to redefine it Katy Demarais in this world of hundreds of traditional television channels, plus thousands more on the internet. Robert G. Douglass Irene E. Eskridge Audiences are taking advantage of new technology to view programs where and when they want Rebecca Espinoza-Kubacki them on a device of their choice.