Sample Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

One and Only

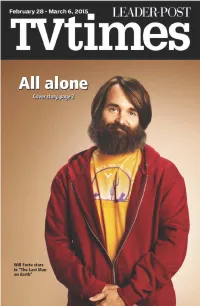

Cover Story One and only Fox tackles the loneliest number in ‘The Last Man on Earth’ By Cassie Dresch people after a virus takes out him get into a lot of really silly TV Media all of Earth’s population. His shenanigans. family is gone, his coworkers “It’s all just kind of stupid ello? Hi? Anybody out are gone, the president is gone. stuff that I go around and do,” Hthere? Of course there is, Everyone. Gone. he said in an interview with otherwise life would be very, So what does he do? He “Entertainment Weekly.” very, very lonely. Fox is taking a travels the United States doing “That’s been one of the most stab at the ultimate life of lone- things he never would have fun parts of the job. About once liness in the new half-hour been able to do otherwise — a week I get to do something comedy “The Last Man on sing the national anthem at that seems like it’d be amaz- Earth,” premiering Sunday, Dodger Stadium, smear gooey ingly fun to do: shoot a flame March 1. peanut butter all over a price- thrower at a bunch of wigs, The premise around “Last less piece of art ... then walk have a steamroller steamroll Man” is a simple one, albeit a away with it, break things. The over a case of beer. Just dumb little strange. An average, un- show, according to creator and stuff like that, which pretty assuming man is on the hunt star Will Forte (“Saturday Night much is all it takes to make me for any signs of other living Live,” “Nebraska,” 2013), sees happy.” Registration $25.00 online: www.skseniorsmechanism.ca or phone 306-359-9956 2 Cover Story Flame throwers and steam- ally proud of what has come rollers? Again, it’s a strange out of it so far.” concept, but Fox is really be- Of course, you have to won- Index hind the show. -

Tvtimes Are Calling Every Day Is Exceptional at Meadowood Call 812-336-7060 to Tour

-711663-1 HT AndyMohrHonda.com AndyMohrHyundai.com S. LIBERTY DRIVE BLOOMINGTON, IN THE HERALD-TIMES | THE TIMES-MAIL | THE REPORTER-TIMES | THE MOORESVILLE-DECATUR TIMES August 3 - 9, 2019 NEW ADVENTURES TVTIMES ARE CALLING EVERY DAY IS EXCEPTIONAL AT MEADOWOOD CALL 812-336-7060 TO TOUR. -577036-1 HT 2455 N. Tamarack Trail • Bloomington, IN 47408 812-336-7060 www.MeadowoodRetirement.com 2019 Pet ©2019 Five Star Senior Living Friendly Downsizing? CALL THE RESULTS TEAM Brokered by: | Call Jenivee 317-258-0995 or Lesaesa 812-360-3863 FREE DOWNSIZING Solving Medical Mysteries GUIDE “Flip or Flop” star and former cancer patient Tarek El -577307-1 Moussa is living proof behind the power of medical HT crowdsourcing – part of the focus of “Chasing the Cure,” a weekly live broadcast and 24/7 global digital platform, premiering Thursday at 9 p.m. on TNT and TBS. Senior Real Estate Specialist JENIVEE SCHOENHEIT LESA OLDHAM MILLER Expires 9/30/2019 (812) 214-4582 HT-698136-1 2019 T2 | THE TV TIMES| The Unacknowledged ‘Mother of Modern Dish Communications’ Bedford DirecTV Cable Mitchell Comcast Comcast Comcast New Wave New New Wave New Mooreville Indianapolis Indianapolis Bloomington Conversion Martinsviolle BY DAN RICE television for Lionsgate. “It is one of those rare initiatives that WTWO NBC E@ - - - - - - - With the availability, cost E# seeks to inspire with a larger S WAVE NBC - 3 - - - - - and quality of healthcare being $ A WTTV CBS E 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 humanitarian purpose, and T such hot-button issues these E^ WRTV ABC 6 6 6 6 - 6 6 URDAY, -

Team Checklist I Have the Complete Set 1975/76 Monty Gum Footballers 1976

Nigel's Webspace - English Football Cards 1965/66 to 1979/80 Team checklist I have the complete set 1975/76 Monty Gum Footballers 1976 Coventry City John McLaughlan Robert (Bobby) Lee Ken McNaught Malcolm Munro Coventry City Jim Pearson Dennis Rofe Jim Brogan Neil Robinson Steve Sims Willie Carr David Smallman David Tomlin Les Cartwright George Telfer Mark Wallington Chris Cattlin Joe Waters Mick Coop Ipswich Town Keith Weller John Craven Ipswich Town Steve Whitworth David Cross Kevin Beattie Alan Woollett Alan Dugdale George Burley Frank Worthington Alan Green Ian Collard Steve Yates Peter Hindley Paul Cooper James (Jimmy) Holmes Eric Gates Manchester United Tom Hutchison Allan Hunter Martin Buchan Brian King David Johnson Steve Coppell Larry Lloyd Mick Lambert Gerry Daly Graham Oakey Mick Mills Alex Forsyth Derby County Roger Osborne Jimmy Greenhoff John Peddelty Gordon Hill Derby County Brian Talbot Jim Holton Geoff Bourne Trevor Whymark Stewart Houston Roger Davies Clive Woods Tommy Jackson Archie Gemmill Steve James Charlie George Leeds United Lou Macari Kevin Hector Leeds United David McCreery Leighton James Billy Bremner Jimmy Nicholl Francis Lee Trevor Cherry Stuart Pearson Roy McFarland Allan Clarke Alex Stepney Graham Moseley Eddie Gray Anthony (Tony) Young Henry Newton Frank Gray David Nish David Harvey Middlesbrough Barry Powell Norman Hunter Middlesbrough Bruce Rioch Joe Jordan David Armstrong Rod Thomas - 3 Peter Lorimer Stuart Boam Colin Todd Paul Madeley Peter Brine Everton Duncan McKenzie Terry Cooper Gordon McQueen John Craggs Everton Paul Reaney Alan Foggon John Connolly Terry Yorath John Hickton Terry Darracott Willie Maddren Dai Davies Leicester City David Mills Martin Dobson Leicester City Robert (Bobby) Murdoch David Jones Brian Alderson Graeme Souness Roger Kenyon Steve Earle Frank Spraggon Bob Latchford Chris Garland David Lawson Len Glover Newcastle United Mick Lyons Steve Kember Newcastle United This checklist is to be provided only by Nigel's Webspace - http://cards.littleoak.com.au/. -

Brian Clough and Peter Taylor

Made in Derby 2018 Profile Brian Clough and Peter Taylor Brian Clough and Peter Taylor. Two names that will always be associated with Derby County. They met as young players – Brian a centre-forward and Peter a goalkeeper – at Middlesbrough FC, where they played together for six years. With a shared passion for the beautiful game they formed a friendship that would take them to the very top of English and European football. They first joined forces as managers at Hartlepool United but it was at Derby County where the dynamic duo, as they were known, had their first taste of the big time. Many of Derby's greatest names were signed in the Clough-Taylor era: Roy McFarland, John O'Hare, Alan Hinton, John McGovern, Willie Carlin, Dave Mackay, Colin Todd and Archie Gemmill to name a few. The two managers and their magnificent team took the Rams to the very top, winning the Division One Championship in 1972 and reaching the European Cup semi-finals. The pair controversially resigned early in the 1973-74 season and the partnership broke up briefly, only be reunited at Nottingham Forest in 1976 where they won many accolades, including two European Cups. But it was at Derby County where the partnership first flourished and Taylor’s daughter, Wendy Dickinson, in a biography of her father, said: “When dad and Brian arrived at the Baseball Ground in May, 1967 it was as if Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid had ridden into town, all guns blazing. These two bright young upstarts were a breath of fresh air at a club that was stuck in the past.” She said her dad was “passionate” about managing Derby and added: “My mum remembers driving down to Derby for the first time and dad said, ‘I wonder what the supporters are like?’ He later said he thought they were the best in the country.” The success of that Derby County team affected everyone in the town and amazing results week after week sent people to work on a Monday morning with a spring in their step. -

The Best Football Films You Have Probably Never Seen by Stuart Fuller

The best football films you have probably never seen by Stuart Fuller Films about football have never been that well received by critics for a number of reasons. We’ve all seen Escape to Victory and marvelled at the footballing skill of Sylvester Stallone and the acting ability of Bobby Moore (or was it the other way round?) or the unlikely storylines of the FIFA- approved Goal trilogy, cringe worthy Sheffield United epic, When Saturday Comes. But there are some decent football-related films out there, especially when they recreate actual events. The five below are our top picks where semi-unbelievable story lines, bad acting and woefully choreographed footballing action is left on the cutting room floor. The Miracle of Bern (2003) One of the biggest shocks in World Cup history is now known as ‘the miracle of Bern’ – the name for West Germany’s triumph in the 1954 finals, when Sepp Herberger’s unfancied side beat Hungary’s ‘magic Magyars’ of Puskas and co. Such was the impact of the victory on national consciousness that it’s often seen as a herald of Germany’s economic and political recovery after the war. The tournament also gave us one of the most famous footballing quotes when Herberger was asked whether his side could recover from an earlier heavy defeat to Hungary to beat them in the final. His response was “The ball is round. The game lasts ninety minutes. This much is fact. Everything else is theory.” Director Sönke Wortmann tells the story through the eyes of 11-year-old Matthias, boot polisher to local footballer Helmut Rahn (who would go on to score the winning goal in 1954). -

Basque Soccer Madness a Dissertation Submitted in Partial

University of Nevada, Reno Sport, Nation, Gender: Basque Soccer Madness A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Basque Studies (Anthropology) by Mariann Vaczi Dr. Joseba Zulaika/Dissertation Advisor May, 2013 Copyright by Mariann Vaczi All Rights Reserved THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the dissertation prepared under our supervision by Mariann Vaczi entitled Sport, Nation, Gender: Basque Soccer Madness be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Joseba Zulaika, Advisor Sandra Ott, Committee Member Pello Salaburu, Committee Member Robert Winzeler, Committee Member Eleanor Nevins, Graduate School Representative Marsha H. Read, Ph. D., Dean, Graduate School May, 2013 i Abstract A centenarian Basque soccer club, Athletic Club (Bilbao) is the ethnographic locus of this dissertation. From a center of the Industrial Revolution, a major European port of capitalism and the birthplace of Basque nationalism and political violence, Bilbao turned into a post-Fordist paradigm of globalization and gentrification. Beyond traditional axes of identification that create social divisions, what unites Basques in Bizkaia province is a soccer team with a philosophy unique in the world of professional sports: Athletic only recruits local Basque players. Playing local becomes an important source of subjectivization and collective identity in one of the best soccer leagues (Spanish) of the most globalized game of the world. This dissertation takes soccer for a cultural performance that reveals relevant anthropological and sociological information about Bilbao, the province of Bizkaia, and the Basques. Early in the twentieth century, soccer was established as the hegemonic sports culture in Spain and in the Basque Country; it has become a multi- billion business, and it serves as a powerful political apparatus and symbolic capital. -

1987-04-05 Liverpool

ARSENAL vLIVERPOOL thearsenalhistory.com SUNDAY 5th APRIL 1987 KICK OFF 3. 5pm OFFICIAL SOUVENIR "'~ £1 ~i\.c'.·'A': ·ttlewcrrJs ~ CHALLENGE• CUP P.O. CARTER, C.B.E. SIR JOHN MOORES, C.B.E. R.H.G. KELLY, F.C.l.S. President, The Football League President, The Littlewoods Organisation Secretary, The Football League 1.30 p.m. SELECTIONS BY THE BRISTOL UNICORNS YOUTH BAND (Under the Direction of Bandmaster D. A. Rogers. BEM) 2.15 p.m. LITTLEWOODS JUNIOR CHALLENGE Exhibition 6-A-Side Match organised by the National Association of Boys' Clubs featuring the Finalists of the Littlewoods Junior Challenge Cup 2.45 p.m. FURTHER SELECTIONS BY THE BRISTOL UNICORNS YOUTH BAND 3.05 p.m. PRESENTATION OF THE TEAMS TO SIR JOHN MOORES, C.B.E. President, The Littlewoods Organisation NATIONAL ANTHEM 3.15 p.m. KICK-OFF 4.00 p.m. HALF TIME Marching Display by the Bristol Unicorns Youth Band 4.55 p.m. END OF MATCH PRESENTATION OF THE LITTLEWOODS CHALLENGE CUP BY SIR JOHN MOORES Commemorative Covers The official commemorative cover for this afternoon's Littlewoods Challenge Cup match Arsenal v Liverpool £1.50 including post and packaging Wembley offers these superbly designed covers for most major matches played at the Stadium and thearsenalhistory.com has a selection of covers from previous League, Cup and International games available on request. For just £1.50 per year, Wembley will keep you up to date on new issues and back numbers, plus occasional bargain packs. MIDDLE TAR As defined by H.M. Government PLEASE SEND FOR DETAILS to : Mail Order Department, Wembley Stadium Ltd, Wembley, Warning: SMOKING CAN CAUSE HEART DISEASE Middlesex HA9 ODW Health Departments' Chief Medical Officers Front Cover Design by: CREATIVE SERVICES, HATFIELD 3 ltlewcms ARSENAL F .C. -

Triumph and Tragedy: the Alan Hinton Story’, by Alan Hinton (With Charlie Bamforth)

Geoffrey Publications is delighted to announce the imminent availability of a new book, ‘Triumph and Tragedy: The Alan Hinton Story’, by Alan Hinton (with Charlie Bamforth). Few indeed are the people who can claim to have been intimately involved in professional football for more than 60 years. Fewer still are those who can justly say that they reached the very top as a player, a coach and as an ambassador for the game. And surely nobody else can say that they did this whilst somehow trying to come to terms with the tragic death of a child. Soccer has been the lifeblood of Alan Hinton since he was a young Wednesbury lad watching Wolverhampton Wanderers and West Bromwich Albion, imploring visiting supporters to send him their clubs’ programmes. He left school at not-quite-15 years old to join the ground staff at Wolves. He was, literally, taken under the wing of the legendary Jimmy Mullen and transformed into a dynamic, completely two-footed left winger with a dynamic shot who was top scorer in Stanley Cullis’ young Wanderers team of the early sixties. The youngster never got too big for his boots - and this book gives endless stories of his down-to-earth nature. For example, how many modern players would be making their way to and from work on two buses and going home to share a bed with his brother after making his England debut, aged 19? Wolves fans were devastated when their ‘Noddy’ was let go to Nottingham Forest in 1964, though not so heartbroken as Hinton himself. -

Kahlil Gibran a Tear and a Smile (1950)

“perplexity is the beginning of knowledge…” Kahlil Gibran A Tear and A Smile (1950) STYLIN’! SAMBA JOY VERSUS STRUCTURAL PRECISION THE SOCCER CASE STUDIES OF BRAZIL AND GERMANY Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Susan P. Milby, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2006 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Melvin Adelman, Adviser Professor William J. Morgan Professor Sarah Fields _______________________________ Adviser College of Education Graduate Program Copyright by Susan P. Milby 2006 ABSTRACT Soccer playing style has not been addressed in detail in the academic literature, as playing style has often been dismissed as the aesthetic element of the game. Brief mention of playing style is considered when discussing national identity and gender. Through a literature research methodology and detailed study of game situations, this dissertation addresses a definitive definition of playing style and details the cultural elements that influence it. A case study analysis of German and Brazilian soccer exemplifies how cultural elements shape, influence, and intersect with playing style. Eight signature elements of playing style are determined: tactics, technique, body image, concept of soccer, values, tradition, ecological and a miscellaneous category. Each of these elements is then extrapolated for Germany and Brazil, setting up a comparative binary. Literature analysis further reinforces this contrasting comparison. Both history of the country and the sport history of the country are necessary determinants when considering style, as style must be historically situated when being discussed in order to avoid stereotypification. Historic time lines of significant German and Brazilian style changes are determined and interpretated. -

Football Photos FPM01

April 2015 Issue 1 Football Photos FPM01 FPG028 £30 GEORGE GRAHAM 10X8" ARSENAL FPK018 £35 HOWARD KENDALL 6½x8½” EVERTON FPH034 £35 EMLYN HUGHES 6½x8½" LIVERPOOL FPH033 £25 FPA019 £25 GERARD HOULLIER 8x12" LIVERPOOL RON ATKINSON 12X8" MAN UTD FPF021 £60 FPC043 £60 ALEX FERGUSON BRIAN CLOUGH 8X12" MAN UTD SIGNED 6½ x 8½” Why not sign up to our regular Sports themed emails? www.buckinghamcovers.com/family Warren House, Shearway Road, Folkestone, Kent CT19 4BF FPM01 Tel 01303 278137 Fax 01303 279429 Email [email protected] Manchester United FPB002 £50 DAVID BECKHAM FPB036 NICKY BUTT 6X8” .....................................£15 8X12” MAGAZINE FPD019 ALEX DAWSON 10X8” ...............................£15 POSTER FPF009 RIO FERDINAND 5X7” MOUNTED ...............£20 FPG017A £20 HARRY GREGG 8X11” MAGAZINE PAGE FPC032 £25 JACK CROMPTON 12X8 FPF020 £25 ALEX FERGUSON & FPS003 £20 PETER SCHMEICHEL ALEX STEPNEY 8X10” 8X12” FPT012A £15 FPM003 £15 MICKY THOMAS LOU MACARI 8X10” MAN UTD 8X10” OR 8X12” FPJ001 JOEY JONES (LIVERPOOL) & JIMMY GREENHOFF (MAN UNITED) 8X12” .....£20 FPM002 GORDON MCQUEEN 10X8” MAN UTD ..£20 FPD009 £25 FPO005 JOHN O’SHEA 8X10” MAGAZINE PAGE ...£5 TOMMY DOCHERTY FPV007A RUUD VAN NISTELROOY 8X12” 8X10” MAN UNITED PSV EINDHOVEN ..............................£25 West Ham FPB038A TREVOR BROOKING 12X8 WEST HAM . £20 FPM042A ALVIN MARTIN 8X10” WEST HAM ...... £10 FPC033 ALAN CURBISHLEY 8X10 WEST HAM ... £10 FPN014A MARK NOBLE 8X12” WEST HAM ......... £15 FPD003 JULIAN DICKS 8X10” WEST HAM ........ £15 FPP006 GEOFF PIKE 8X10” WEST HAM ........... £10 FPD012 GUY DEMEL 8X12” WEST HAM UTD..... £15 FPP009 GEORGE PARRIS 8X10” WEST HAM .. £7.50 FPD015 MOHAMMED DIAME 8X12” WEST HAM £10 FPP012 PHIL PARKES 8X10” WEST HAM ........ -

Series Checklist I Have the Complete Set 1971/72 A&BC Chewing Gum (English) Footballer, Purple Backs

Nigel's Webspace - English Football Cards 1965/66 to 1979/80 Series checklist I have the complete set 1971/72 A&BC chewing gum (English) Footballer, Purple backs 001 Frank Clark Newcastle United 046 Alan Birchenall Crystal Palace 002 Alan Ball Everton 047 Steve Heighway Liverpool 003 Jeff Astle West Bromwich Albion 048 Pat Rice Arsenal 004 Gareth (Gary) Sprake Leeds United 049 Derek Dougan Wolverhampton Wanderers 005 Peter Bonetti Chelsea 050 Mick Mills Ipswich Town 006 Frank McLintock Arsenal 051 John Hollins Chelsea 007 John Toshack Liverpool 052 Paul Edwards Manchester United 008 Jimmy Robertson Ipswich Town 053 Colin Harvey Everton 009 Bobby Charlton Manchester United 054 Eric Martin Southampton 010 Colin Todd Derby County 055 Archie Gemmill Derby County 011 Bobby Moncur Newcastle United 056 Frank Worthington Huddersfield Town 012 Colin Bell Manchester City 057 Checklist, Series 1, cards 1- 109 013 Tom Jenkins Southampton 058 Joe Kinnear Tottenham Hotspur 014 Phil Parkes Wolverhampton Wanderers 059 Tony Book Manchester City 015 Gordon Banks Stoke City 060 Brian Harris Cardiff City 016 David Payne Crystal Palace 061 Brian Joicey Coventry City 017 Dennis Clarke Huddersfield Town 062 Robert (Sammy) Chapman Nottingham Forest 018 Bobby Moore West Ham United 063 Tommy Taylor West Ham United 019 Mel Sutton Cardiff City 064 Denis Smith Stoke City 020 Martin Chivers Tottenham Hotspur 065 Peter Houseman Chelsea 021 Geoff Strong Coventry City 066 Tony Brown West Bromwich Albion 022 Ian Storey-Moore Nottingham Forest 067 Brian O'Neil Southampton -

World Cup Booklet

THE HISTORY OF THE WORLD CUP Written by BRIAN GLANVILLE Read by BOB WILSON Sir Bobby Charlton remembers his three NA440412D World Cup appearances 1 Introduction – Bob Wilson 2:08 2 Sir Bobby Charlton – the significance of the World Cup for the player 0:34 3 A world cup for football – the concept 4:56 4 1930 URUGUAY 6:17 5 Semi-Finals: Argentina v USA; Uruguay v Yugoslavia 3:54 6 1934 ITALY 3:45 7 The tournament was played on a straight knock-out basis… 3:54 8 The Final: Italy v Czechoslovakia 2:15 9 1938 FRANCE 7:57 10 The Semi-Finals: Hungary v Sweden; Italy v Brazil 1:36 11 The Final: Italy v Hungary 1:55 12 1950 BRAZIL 9:52 13 The final pool: Uruguay, Brazil, Spain, Sweden 0:37 14 The Final: Brazil v Uruguay 3:26 15 1954 SWITZERLAND 6:10 16 The Quarter-Finals 1:29 17 The Semi-Finals: Hungary v Uruguay; West Germany v Austria 0:40 18 The Final: West Germany v Hungary 2:15 2 19 1958 SWEDEN 8:26 20 The Quarter-Finals 1:04 21 The Semi-Finals: Sweden v West Germany; Brazil v France 1:03 22 The Final: Sweden v Brazil 1:40 23 1962 CHILE 3:53 24 The Quarter-Finals 1:44 25 The Semi-Finals: Brazil v Chile; Czechoslovakia v Yugoslavia 1:08 26 The Final: Brazil v Czechoslovakia 1:53 27 1966 ENGLAND 5:27 28 The Quarter-Finals 2:41 29 The Semi-Finals: England v Portugal; West Germany v Soviet Union 2:26 30 The Final: England v Germany 3:40 31 1970 MEXICO 7:25 32 The Quarter-Finals 2:45 33 The Semi-Finals: Italy v West Germany; Brazil v Uruguay 0:54 34 The Final: Brazil v Italy 2:18 35 1974 WEST GERMANY 5:35 36 Two Final Pools 1:25 37 The Final: Germany