Strict Liability, Nuisance and Legislative Authorization Allen M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case 2:12-Cv-01114-JD Document 17 Filed 10/19/12 Page 1 of 9

Case 2:12-cv-01114-JD Document 17 Filed 10/19/12 Page 1 of 9 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA _____________________________________ DAVID S. TATUM, : CIVIL ACTION : NO. 12-1114 : Plaintiff, : v. : : TAKEDA PHARMACEUTICALS : NORTH AMERICA, INC., TAKEDA PHARMACEUTICALS AMERICA, INC., : TAKEDA PHARMACEUTICALS : INTERNATIONAL, INC., TAKEDA : PHARMACEUTICALS COMPANY : LIMITED, TAKEDA PHARMACEUTICALS, LLC, TAKEDA : AMERICA HOLDINGS, INC., TAKEDA : GLOBAL RESEARCH & : DEVELOPMENT CENTER, INC., : TAKEDA SAN DIEGO, INC., TAP : PHARMACEUTICALS PRODUCTS, INC., ABBOTT LABORATORIES, INC., : DOES 1 THROUGH 100 INCLUSIVE, : : Defendants. : _____________________________________ DuBois, J. October 18, 2012 M E M O R A N D U M I. INTRODUCTION This is a product liability action in which plaintiff David S. Tatum alleges that the PREVACID designed, manufactured, and marketed by defendants weakened his bones, ultimately leading to hip fractures. The defendants filed a motion to dismiss many of the claims in Tatum’s First Amended Complaint. For the reasons that follow, the Court grants in part and denies in part defendants’ motion. II. BACKGROUND1 Tatum was prescribed PREVACID, a pharmaceutical drug designed, manufactured, and 1 As required on a motion to dismiss, the Court takes all plausible factual allegations contained in plaintiff’s First Amended Complaint to be true. Case 2:12-cv-01114-JD Document 17 Filed 10/19/12 Page 2 of 9 marketed by defendants. (Am. Compl. 3, 7.) After taking PREVACID, Tatum began feeling pain in his left hip, and he was later diagnosed with Stage III Avascular Necrosis. (Id. at 7.) Tatum’s bones became weakened or brittle, causing multiple fractures. -

Sniadach, the Replevin Cases and Self-Help Repossession -- Due Process Tokenism? Julian B

Boston College Law Review Volume 14 Article 2 Issue 3 Number 3 2-1-1973 Sniadach, The Replevin Cases and Self-Help Repossession -- Due Process Tokenism? Julian B. McDonnell Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr Part of the Fourteenth Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Julian B. McDonnell, Sniadach, The Replevin Cases and Self-Help Repossession -- Due Process Tokenism?, 14 B.C.L. Rev. 437 (1973), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr/vol14/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SNIADACH, THE REPLEVIN CASES AND SELF-HELP REPOSSESSION-DUE PROCESS TOKENISM? JULIAN B. MCDONNELL* Last term, a divided United States Supreme Court invalidated the replevin statutes of Pennsylvania and Florida. In Fuentes v. Shevinl and Parham v. Cortese' (the Replevin Cases), the Court held these statutes unconstitutional insofar as they authorized repossession of collateral through state officials before the debtor was notified of the attempted repossession and accorded an opportunity to be heard on the merits of the creditor's claim. The Replevin Cases involved typical consumer purchases of household pods,' and accordingly raised new questions about the basic relationship between secured creditors and consumer debtors—a relationship upon which our consumer credit economy is based. Creditors have traditionally regarded the right to immediate repossession of collateral after determining the debtor to be in default as the essence of personal property security arrange- ments,' and their standard-form security agreements typically spell out this right. -

July 25, 2019 NACDL OPPOSES AFFIRMATVE CONSENT

July 25, 2019 NACDL OPPOSES AFFIRMATVE CONSENT RESOLUTION ABA RESOLUTION 114 NACDL opposes ABA Resolution 114. Resolution 114 urges legislatures to adopt affirmative consent requirements that re-define consent as: the assent of a person who is competent to give consent to engage in a specific act of sexual penetration, oral sex, or sexual contact, to provide that consent is expressed by words or action in the context of all the circumstances . The word “assent” generally refers to an express agreement. In addition the resolution dictates that consent must be “expressed by words or actions.” The resolution calls for a new definition of consent in sexual assault cases that would require expressed affirmative consent to every sexual act during the course of a sexual encounter. 1. Burden-Shifting in Violation of Due Process and Presumption of Innocence: NACDL opposes ABA Resolution 114 because it shifts the burden of proof by requiring an accused person to prove affirmative consent to each sexual act rather than requiring the prosecution to prove lack of consent. The resolution assumes guilt in the absence of any evidence regarding consent. This radical change in the law would violate the Due Process Clause of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments and the Presumption of Innocence. It offends fundamental and well-established notions of justice. Specifically, Resolution 114 urges legislatures to re-define consent as “the assent of a person who is competent to give consent to engage in a specific act of sexual penetration, oral sex, or sexual contact, to provide that consent is expressed by words or action in the context of all the circumstances . -

The Constitutionality of Strict Liability in Sex Offender Registration Laws

THE CONSTITUTIONALITY OF STRICT LIABILITY IN SEX OFFENDER REGISTRATION LAWS ∗ CATHERINE L. CARPENTER INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 296 I. STATUTORY RAPE ............................................................................... 309 A. The Basics.................................................................................... 309 B. But the Victim Lied and Why it Is Irrelevant: Examining Strict Liability in Statutory Rape........................................................... 315 C. The Impact of Lawrence v. Texas on Strict Liability................... 321 II. A PRIMER ON SEX OFFENDER REGISTRATION LAWS AND THE STRICT LIABILITY OFFENDER.............................................................. 324 A. A Historical Perspective.............................................................. 324 B. Classification Schemes ................................................................ 328 C. Registration Requirements .......................................................... 331 D. Community Notification Under Megan’s Law............................. 336 III. CHALLENGING THE INCLUSION OF STRICT LIABILITY STATUTORY RAPE IN SEX OFFENDER REGISTRATION.............................................. 338 A. General Principles of Constitutionality Affecting Sex Offender Registration Laws........................................................................ 323 1. The Mendoza-Martinez Factors............................................. 338 2. Regulation or -

Torts - Trespass to Land - Liability for Consequential Injuries Charley J

Louisiana Law Review Volume 21 | Number 4 June 1961 Torts - Trespass To land - Liability for Consequential Injuries Charley J. S. Schrader Jr. Repository Citation Charley J. S. Schrader Jr., Torts - Trespass To land - Liability for Consequential Injuries, 21 La. L. Rev. (1961) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol21/iss4/23 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 862 LOUISIANA LAW REVIEW [Vol. XXI is nonetheless held liable for the results of his negligence. 18 It would seem that this general rule that the defendant takes his victim as he finds him would be equally applicable in the instant type of case. The general rule, also relied upon to some extent by the court in the instant case, that a defendant is not liable for physical injury resulting from a plaintiff's fear for a third person, has had its usual application in situations where the plaintiff is not within the zone of danger.' 9 Seemingly, the reason for this rule is to enable the courts to deal with case where difficulties of proof militate against establishing the possibility of recovery. It would seem, however, that in a situation where the plaintiff is within the zone of danger and consequently could recover if he feared for himself, the mere fact that he feared for another should not preclude recovery. -

Torts Mnemonics

TORTS MNEMONICS 1) Torts are done IN SIN: I – INTENTIONAL harm to a person (e.g., assault, battery, false imprisonment, or the intentional infliction of emotional harm) N – NEGLIGENT conduct causing personal injury, wrongful death, or prop damage S – STRICT tort liability I – INTENTIONAL harm to property (e.g., trespass, conversion, or tortious interference with a contract) N – NUISANCE 2) Tortious conduct makes you want to SING: S – STRICT tort liability I – INTENTIONAL conduct N – NEGLIGENT conduct G – GROSS negligence a/k/a reckless conduct 3) A D’s FIT conduct is unreasonable/negligent when P was within the foreseeable zone of danger: F – FAILURE to take reasonable precautions in light of foreseeable risks I – INADVERTENCE T – THOUGHTLESSNESS 4) To establish a negligence claim, P must mix the right DIP: D – DUTY to exercise reasonable care was owed by the D to the injured P and the D breached this duty (for a negligence claim the duty is always to conform to the legal standard of reasonable conduct in light of the apparent risks) I – Physical INJURY to the P or his property (damages) P – P’s injuries were PROXIMATELY caused by the D’s breach of duty 5) A parent is liable only for the torts of a SICK child: S – in an employment relationship where a child commits a tort, while acting as a SERVANT or agent of the parent I – where the parent entrusts or knowingly leaves in the child’s possession an INSTRUMENTALITY that, in light of the child’s age, intelligence, disposition and prior experience, creates an unreasonable risk of harm to -

A Law and Norms Critique of the Constitutional Law of Defamation

PASSAPORTISBOOK 10/21/2004 7:39 PM NOTE A LAW AND NORMS CRITIQUE OF THE CONSTITUTIONAL LAW OF DEFAMATION Michael Passaportis* INTRODUCTION................................................................................. 1986 I. COLLECTIVE ACTION PROBLEMS AND RATIONAL CHOICE THEORY....................................................................................... 1988 II. BEHAVIORAL ECONOMICS AND NORMS .................................. 1990 III. ESTEEM, GOSSIP, AND FALSE GOSSIP ...................................... 1994 A. The Negative Externality of False Gossip ......................... 1995 B. Punishment of False Negative Gossip ............................... 2001 IV. THE LAW OF DEFAMATION AND ITS CONSTITUTIONALIZATION ........................................................ 2004 A. Defamation at Common Law............................................. 2005 B. The Constitutional Law of Defamation............................. 2008 V. THE CONSTITUTIONAL LAW OF DEFAMATION AND NORMS . 2013 A. The Problem of Under-Produced Political Speech.......... 2013 B. The Actual Malice Rule and Normative Behavior ........... 2019 VI. THE COMMON LAW VERSUS SULLIVAN FROM A LAW AND ECONOMICS PERSPECTIVE......................................................... 2022 A. The Economics of Strict Liability ...................................... 2022 B. Strict Liability and Defamation.......................................... 2027 C. Was the Common Law of Defamation Efficient? ............ 2032 CONCLUSION.................................................................................... -

Is There Really No Liability Without Fault?: a Critique of Goldberg & Zipursky

IS THERE REALLY NO LIABILITY WITHOUT FAULT?: A CRITIQUE OF GOLDBERG & ZIPURSKY Gregory C. Keating* INTRODUCTION In their influential writings over the past twenty years and most recently in their article “The Strict Liability in Fault and the Fault in Strict Liability,” Professors Goldberg and Zipursky embrace the thesis that torts are conduct-based wrongs.1 A conduct-based wrong is one where an agent violates the right of another by failing to conform her conduct to the standard required by the law.2 As a description of negligence liability, the characterization of torts as conduct-based wrongs is both correct and illuminating. Negligence involves a failure to conduct oneself as a reasonable person would. It is fault in the deed, not fault in the doer. At least since Vaughan v. Menlove,3 it has been clear that a blameless injurer can conduct himself negligently and so be held liable.4 Someone who fails to conform to the standard of conduct expected of the average reasonable person and physically harms someone else through such failure is prima * William T. Dalessi Professor of Law and Philosophy, USC Gould School of Law. I am grateful to John Goldberg and Ben Zipursky both for providing a stimulating paper and for feedback on this Article. Daniel Gherardi provided valuable research assistance. 1. John C.P. Goldberg & Benjamin C. Zipursky, The Strict Liability in Fault and the Fault in Strict Liability, 85 FORDHAM L. REV. 743, 745 (2016) (“[F]ault-based liability is . liability predicated on some sort of wrongdoing. [L]iability rests on the defendant having been ‘at fault,’ i.e., having failed to act as required.”). -

Contra Costa Superior Court Martinez, California Department: 21 Hearing Date: 01/30/19

CONTRA COSTA SUPERIOR COURT MARTINEZ, CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT: 21 HEARING DATE: 01/30/19 1. TIME: 9:00 CASE#: MSC16-01717 CASE NAME: JOHNSON VS. COUNTY OF CONTRA COSTA HEARING ON TRIAL RE-SETTING * TENTATIVE RULING: * Parties to appear. CourtCall is acceptable if there is no argument on line 2. 2. TIME: 9:00 CASE#: MSC16-01717 CASE NAME: JOHNSON VS. COUNTY OF CONTRA COSTA HEARING ON DEMURRER TO COMPLAINT FILED BY BAILEY T. LEE, M.D. * TENTATIVE RULING: * The demurrer of defendant Bailey Lee, M.D., to plaintiffs’ complaint is overruled. Defendant shall file and serve his Answer on or before February 13, 2019. Plaintiffs filed this medical malpractice case on September 6, 2016 against defendant Contra Costa County, several physicians, and Does 1-100. Plaintiffs contend they discovered possible liability on the part of Dr. Lee several years after they suit, based upon conversations with an expert consultant. Shortly thereafter, they filed a Doe amendment on September 25, 2018, naming Dr. Lee as Doe 1. Dr. Lee now demurs to the complaint. He argues that the complaint contains no charging allegations against him and that it is uncertain. (CCP § 403.10 (e), (f).) A party who is ignorant of the name of a defendant or the basis for a defendant’s liability may name that defendant by a fictitious name and amend to state the defendant’s true name when the facts are discovered. (CCP § 474; see Breceda v. Gamsby (1968) 267 Cal.App.2d 167, 174.) If section 474 is properly used, no amendment of the complaint is necessary other than the Doe amendment itself. -

I. A. Intellectual Approaches to Tort Law 1. Corrective Justice 2. Economic Approach/Deterrence Approach 3. Compensation Approac

Torts, Sharkey Fall 2006, Dave Fillingame I. INTRODUCTION A. Intellectual Approaches to Tort Law 1. Corrective Justice 2. Economic Approach/Deterrence Approach 3. Compensation Approach B. Holmes: Two theories of common-law liability: 1. Criminalist (Negligence) 2. “A man acts at his own peril” (strict liability) 3. Judge People by an Objective not a Subjective Standard of Care C. Judge v. Jury in Torts II. INTENTIONAL TORTS A. Elements B. Physical Harms 1. Battery a. Eggshell Skull Rule (Vosburg v. Putney) b. Intent to Act v. Intent to Harm c. “Substantial Certainty” Test (Garratt v. Dailey) d. “Playing Piano” (White v. University of Idaho) e. “Transferred” Intent 2. Defenses to Battery: Consent a. Consent b. Consent: Implied License c. Consent to Illegal Acts 3. Defenses to Battery: Insanity 4. Defenses to Battery: Self-Defense and Defense of Others a. Can be used as a defense when innocent bystanders harmed b. Can be used in defense of third-parties c. Must be proportional force 5. Defenses to Battery: Necessity C. Trespass to Land 1. No Damage is Required, Unauthorized Entry on Land is Enough a. An unfounded claim of right does not make a willful entry innocent. b. Quarum Clausum Fregit 2. Use of Deadly Force in Protection of Property a. Posner: We Must Create Incentives to Protect Tulips and Peacocks. b. Use Reasonable Force: Katko v. Briney (Iowa 1971) 3. Defense of Privilege a. Privilege of Necessity b. “General Average Contribution” c. Conditional (Incomplete) Privilege Vincent v. Lake Erie (Minn. 1910) d. The privilege exists only so long as the necessity does. -

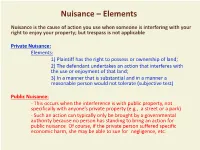

Nuisance – Elements

Nuisance – Elements Nuisance is the cause of action you use when someone is interfering with your right to enjoy your property; but trespass is not applicable Private Nuisance: Elements: 1) Plaintiff has the right to possess or ownership of land; 2) The defendant undertakes an action that interferes with the use or enjoyment of that land; 3) In a manner that is substantial and in a manner a reasonable person would not tolerate (subjective test) Public Nuisance: - This occurs when the interference is with public property, not specifically with anyone’s private property (e.g., a street or a park) - Such an action can typically only be brought by a governmental authority because no person has standing to bring an action for public nuisance. Of course, if the private person suffered specific economic harm, she may be able to sue for negligence, etc. Nuisance - Other Factors - The nuisance must have arisen from an act that’s actionable as an intentional, negligent or strict liability tort! - The actions that give rise to the nuisance must be “unreasonable” under the circumstances. Thus: A “balancing test” must be performed between the harm that the nuisance causes and the benefits of the activities that create the nuisance, taking into account: o The economic and social importance of the activity o The burden on the defendant and on society of forcing the activity to cease o Whether there is a more appropriate place to conduct the activity - All the rules regarding causation and damages apply, as with negligence and strict liability - The defenses of assumption of risk and contributory negligence apply; as with any other tort. -

The Expansion of Fraud, Negligence, and Strict Tort Liability

Michigan Law Review Volume 64 Issue 7 1966 Products Liability--The Expansion of Fraud, Negligence, and Strict Tort Liability John A. Sebert Jr. University of Michigan Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Consumer Protection Law Commons, and the Torts Commons Recommended Citation John A. Sebert Jr., Products Liability--The Expansion of Fraud, Negligence, and Strict Tort Liability, 64 MICH. L. REV. 1350 (1966). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol64/iss7/10 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENTS Products Liability-The Expansion of Fraud, Negligence, and Strict Tort Liability The advances in recent years in the field of products liability have probably outshone, in both number a~d significance, the prog ress during the same period in most other areas of the law. These rapid developments in the law of consumer protection have been marked by a consistent tendency to expand the liability· of manu facturers, retailers, and other members of the distributive chain for physical and economic harm caused by defective merchandise made available to the public. Some of the most notable progress has been made in the law of tort liability. A number of courts have adopted the principle that a manufacturer, retailer, or other seller1 of goods is answerable in tort to any user of his product who suffers injuries attributable to a defect in the merchandise, despite the seller's exer cise of reasonable care in dealing with the product and irrespective of the fact that no contractual relationship has ever existed between the seller and the victim.2 This doctrine of strict tort liability, orig inally enunciated by the California Supreme Court in Greenman v.