The Shadbushes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department of Planning and Zoning

Department of Planning and Zoning Subject: Howard County Landscape Manual Updates: Recommended Street Tree List (Appendix B) and Recommended Plant List (Appendix C) - Effective July 1, 2010 To: DLD Review Staff Homebuilders Committee From: Kent Sheubrooks, Acting Chief Division of Land Development Date: July 1, 2010 Purpose: The purpose of this policy memorandum is to update the Recommended Plant Lists presently contained in the Landscape Manual. The plant lists were created for the first edition of the Manual in 1993 before information was available about invasive qualities of certain recommended plants contained in those lists (Norway Maple, Bradford Pear, etc.). Additionally, diseases and pests have made some other plants undesirable (Ash, Austrian Pine, etc.). The Howard County General Plan 2000 and subsequent environmental and community planning publications such as the Route 1 and Route 40 Manuals and the Green Neighborhood Design Guidelines have promoted the desirability of using native plants in landscape plantings. Therefore, this policy seeks to update the Recommended Plant Lists by identifying invasive plant species and disease or pest ridden plants for their removal and prohibition from further planting in Howard County and to add other available native plants which have desirable characteristics for street tree or general landscape use for inclusion on the Recommended Plant Lists. Please note that a comprehensive review of the street tree and landscape tree lists were conducted for the purpose of this update, however, only -

Amelanchier Canadensis: Shadblow Serviceberry1 Edward F

ENH233 Amelanchier canadensis: Shadblow Serviceberry1 Edward F. Gilman and Dennis G. Watson2 Introduction Availability: somewhat available, may have to go out of the region to find the tree Downy serviceberry is an upright, twiggy, multi-stemmed large shrub, eventually reaching 20 to 25 feet in height with a spread of 15 to 20 feet. This North American native is usually the first to be noticed in the forest or garden at springtime, the pure white, glistening flowers some of the earliest to appear among the many other dull brown, leafless, and still-slumbering trees. The small white flowers are produced in dense, erect, two- to three-inch-long racemes, opening up to a delicate display before the attrac- tive reddish-purple buds unfold into small, rounded leaves. These leaves are covered with a fine, soft grey fuzz when young, giving the plant its common name, but will mature into smooth, dark green leaves later. Following the blooms are many small, luscious, dark red/purple, sweet and juicy, apple-shaped fruits, often well hidden by the dark green leaves, and which would be popular with people were they not so quickly consumed by birds and other wildlife who seem to find their flavor irresistible. General Information Figure 1. Young Amelanchier canadensis: Shadblow Serviceberry Scientific name: Amelanchier canadensis Pronunciation: am-meh-LANG-kee-er kan-uh-DEN-sis Description Common name(s): Shadblow serviceberry Height: 20 to 25 feet Family: Rosaceae Spread: 15 to 20 feet USDA hardiness zones: 4A through 7B (Fig. 2) Crown uniformity: symmetrical Origin: native to North America Crown shape: upright/erect Invasive potential: little invasive potential Crown density: open Uses: specimen; deck or patio; container or planter Growth rate: moderate Texture: fine 1. -

Detecting Signs and Symptoms of Asian Longhorned Beetle Injury

DETECTING SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF ASIAN LONGHORNED BEETLE INJURY TRAINING GUIDE Detecting Signs and Symptoms of Asian Longhorned Beetle Injury TRAINING GUIDE Jozef Ric1, Peter de Groot2, Ben Gasman3, Mary Orr3, Jason Doyle1, Michael T Smith4, Louise Dumouchel3, Taylor Scarr5, Jean J Turgeon2 1 Toronto Parks, Forestry and Recreation 2 Natural Resources Canada - Canadian Forest Service 3 Canadian Food Inspection Agency 4 United States Department of Agriculture - Agricultural Research Service 5 Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources We dedicate this guide to our spouses and children for their support while we were chasing this beetle. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Detecting Signs and Symptoms of Asian Longhorned Beetle Injury : Training / Jozef Ric, Peter de Groot, Ben Gasman, Mary Orr, Jason Doyle, Michael T Smith, Louise Dumouchel, Taylor Scarr and Jean J Turgeon © Her Majesty in Right of Canada, 2006 ISBN 0-662-43426-9 Cat. No. Fo124-7/2006E 1. Asian longhorned beetle. 2. Trees- -Diseases and pests- -Identification. I. Ric, Jozef II. Great Lakes Forestry Centre QL596.C4D47 2006 634.9’67648 C2006-980139-8 Cover: Asian longhorned beetle (Anoplophora glabripennis) adult. Photography by William D Biggs Additional copies of this publication are available from: Publication Office Plant Health Division Natural Resources Canada Canadian Forest Service Canadian Food Inspection Agency Great Lakes Forestry Centre Floor 3, Room 3201 E 1219 Queen Street East 59 Camelot Drive Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario Ottawa, Ontario CANADA P6A 2E5 CANADA K1A 0Y9 [email protected] [email protected] Cette publication est aussi disponible en français sous le titre: Détection des signes et symptômes d’attaque par le longicorne étoilé : Guide de formation. -

Amelanchierspp. Family: Rosaceae Serviceberry

Amelanchier spp. Family: Rosaceae Serviceberry The genus Amelanchier contains about 16 species native to North America [5], Mexico [2], and Eurasia to northern Africa [4]. The word amelanchier is derived from the French common name amelanche of the European serviceberry, Amelanchier ovalis. Amelanchier alnifolia-juneberry, Pacific serviceberry, pigeonberry, rocky mountain servicetree, sarvice, sarviceberry, saskatoon, saskatoon serviceberry, western service, western serviceberry , western shadbush Amelanchier arborea-Allegheny serviceberry, apple shadbush, downy serviceberry , northern smooth shadbush, shadblow, shadblown serviceberry, shadbush, shadbush serviceberry Amelanchier bartramiana-Bartram serviceberry Amelanchier canadensis-American lancewood, currant-tree, downy serviceberry, Indian cherry, Indian pear, Indian wild pear, juice plum, juneberry, may cherry, sugar plum, sarvice, servicetree, shadberry, shadblow, shadbush, shadbush serviceberry, shadflower, thicket serviceberry Amelanchier florida-Pacific serviceberry Amelanchier interior-inland serviceberry Amelanchier sanguinea-Huron serviceberry, roundleaf juneberry, roundleaf serviceberry , shore shadbush Amelanchier utahensis-Utah serviceberry Distribution In North America throughout upper elevations and temperate forests. The Tree Serviceberry is a shrub or tree that reaches a height of 40 ft (12 m) and a diameter of 2 ft (0.6 m). It grows in many soil types and occurs from swamps to mountainous hillsides. It flowers in early spring, producing delicate white flowers, making -

Amelanchier Canadensis

AmelanchierAmelanchier canadensiscanadensis ShadblowShadblow serviceberry,serviceberry, CanadianCanadian serviceberry,serviceberry, DownyDowny serviceberry,serviceberry, Shadbush,Shadbush, Juneberry,Juneberry, ChuckleberryChuckleberry Amelanchier canadensis(Shadblow serviceberry) is native to South Canada and the eastern United States. The shrub was introduced in Europe in 1746. The Shadblow serviceberry grows up to 5 to 6 metres tall and wide with a finely branched, wide vase-shaped crown. Before the leaves start to sprout, the Amelanchier canadensisblooms bountifully racemes of white flowers that hang over slightly. In late July, it bears red-violet to blue-black fruits that are edible. The leaves are relatively large and bud in a lovely bronze-red. In the summer, the Shadblow serviceberry has green leaves with a grey-green underside. The autumn colours are yellow-orange to brown and less striking than those of other serviceberry shrubs. The species has a preference for sunlight and moist, humous, slightly acidic soil. It will tolerate a temporarily dry environment, as well as strong wind. That makes Amelanchier canadensis very suitable for use in containers and roof gardens. SEASONAL COLOURS jan feb mar apr mei jun jul aug sep okt nov dec TYPES OF PLANTING Tree types: fruit trees, solitary shrubs | Topiary on stem: multi-stem umbrella USE Location: park, central reservation, in containers, roof garden, large garden, small garden, patio, cemetery, countryside, ecological zone | Pavement: none, open | Planting concepts: Eco planting, -

Plant Collecting Expedition for Berry Crop Species Through Southeastern

Plant Collecting Expedition for Berry Crop Species through Southeastern and Midwestern United States June and July 2007 Glassy Mountain, South Carolina Participants: Kim E. Hummer, Research Leader, Curator, USDA ARS NCGR 33447 Peoria Road, Corvallis, Oregon 97333-2521 phone 541.738.4201 [email protected] Chad E. Finn, Research Geneticist, USDA ARS HCRL, 3420 NW Orchard Ave., Corvallis, Oregon 97330 phone 541.738.4037 [email protected] Michael Dossett Graduate Student, Oregon State University, Department of Horticulture, Corvallis, OR 97330 phone 541.738.4038 [email protected] Plant Collecting Expedition for Berry Crops through the Southeastern and Midwestern United States, June and July 2007 Table of Contents Table of Contents.................................................................................................................... 2 Acknowledgements:................................................................................................................ 3 Executive Summary................................................................................................................ 4 Part I – Southeastern United States ...................................................................................... 5 Summary.............................................................................................................................. 5 Travelog May-June 2007.................................................................................................... 6 Conclusions for part 1 ..................................................................................................... -

Serviceberry Has Come to Signal a Happy Sign of Spring in the Garden

Notable Natives source of food for wildlife and humans. Over time serviceberry has come to signal a happy sign of spring in the garden. Serviceberry Serviceberry is a tall shrub or small tree reaching from fifteen to twenty-five feet tall. The young elliptical leaves are medium Amelanchier arborea or to dark green in color and are interesting because they have serviceberry is a soft almost woolly “fur” or hairs on their undersides which deciduous shrub in the eventually disappear when the leaves mature. The leaves turn rose family (Rosaceae). a beautiful reddish to pink hue in autumn. The smooth, grey It can play a significant bark can have a reddish cast, and as the plant matures, the role in the Midwest bark grows interesting ridges and shallow furrows. Its slender native garden. There buds and white flowers grow in drooping racemes or bunches are closely related of six to fourteen flowers appearing in spring before mature native species A. Serviceberries in bloom. Photo by Carol Rice. leaves are present. interior and A. laevis, usually from sandier habitats. A tall and narrow woodland The ornamental flowers last only a week or two and are mildly plant, it is one of the first shrubs to flower in spring and is a fragrant. After blooming, the flowers develop into small great plant for residential properties. reddish-purple pomes, small apple-shaped fruits that hang in small clusters. The Serviceberry likes full sun but will tolerate partial sun or light fruit is similar in size to shade. It requires good drainage but should be kept moist blueberries and ripens during summer droughts. -

USDA Plant Guide (Pdf)

Plant Guide stomach problems. Bark and twigs provided a SASKATOON medicine for recovery after childbirth. In Amelanchier alnifolia (Nutt.) combination with other plants, it was used to make a Nutt. ex Roemer contraceptive. The strong and straight-grained wood Plant Symbol = AMAL2 was used to make arrows, digging sticks, spear shafts, tool handles, and seed beaters. Young branches were Contributed By: USDA NRCS National Plant Data twisted into a type of rope. Center & the Biota of North America Program Saskatoon is attractive as an ornamental shrub or may be trimmed as a hedge. It is an important species for reclamation, wildlife, watershed, and shelterbelt plantings. It can be started from seed or vegetative cuttings. Status Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status, such as, state noxious status and wetland indicator values. Description General: Rose Family (Rosaceae). Native shrubs or small trees growing to 7 meters high, variable in growth form, forming thickets, mats, or clumps, the William R. Hewlitt underground portions including a massive root © California Academy of Sciences crown, horizontal and vertical rhizomes, and an @ CalPhotos extensive root system; bark: thin, light brown and tinged with red, smooth or shallowly fissured. Alternate common names Leaves are deciduous, simple, alternate, ovate to Saskatoon service-berry, service-berry, juneberry, nearly round, 2.5-3 cm long, with lateral, parallel shadbush veins in 8-13 pairs, the margins coarsely serrate or dentate to below middle or sometimes entire or with Uses only a few small teeth at the top. Flowers are in Saskatoon is planted as an ornamental and to produce short, dense, 5-15-flowered, upright racemes, the commercial fruit crops. -

Sorbus Torminalis

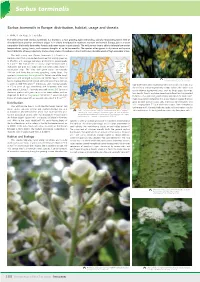

Sorbus torminalis Sorbus torminalis in Europe: distribution, habitat, usage and threats E. Welk, D. de Rigo, G. Caudullo The wild service tree (Sorbus torminalis (L.) Crantz) is a fast-growing, light-demanding, clonally resprouting forest tree of disturbed forest patches and forest edges. It is widely distributed in southern, western and central Europe, but is a weak competitor that rarely dominates forests and never occurs in pure stands. The wild service tree is able to tolerate low winter temperatures, spring frosts, and summer droughts of up to two months. The species often grows in dry-warm and sparse forest habitats of low productivity and on steep slopes. It produces a hard and heavy, durable wood of high economic value. The wild service tree (Sorbus torminalis (L.) Crantz) is a medium-sized, fast-growing deciduous tree that usually grows up to 15-25 m with average diameters of 0.6-0.9 m, exceptionally Frequency 1-3 < 25% to 1.4 m . The mature tree is usually single-stemmed with a 25% - 50% distinctive ash-grey and scaly bark that often peels away in 50% - 75% > 75% rectangular strips. The shiny dark green leaves are typically Chorology 10x7 cm and have five to nine spreading, acute lobes. This Native species is monoecious hermaphrodite, flowers are white, insect pollinated, and arranged in corymbs of 20-30 flowers. The tree Yellow and red-brown leaves in autumn. has an average life span of around 100-200 years; the maximum (Copyright Ashley Basil, www.flickr.com: CC-BY) 1-3 is given as 300-400 years . -

Pinery Provincial Park Vascular Plant List Flowering Latin Name Common Name Community Date

Pinery Provincial Park Vascular Plant List Flowering Latin Name Common Name Community Date EQUISETACEAE HORSETAIL FAMILY Equisetum arvense L. Field Horsetail FF Equisetum fluviatile L. Water Horsetail LRB Equisetum hyemale L. ssp. affine (Engelm.) Stone Common Scouring-rush BS Equisetum laevigatum A. Braun Smooth Scouring-rush WM Equisetum variegatum Scheich. ex Fried. ssp. Small Horsetail LRB Variegatum DENNSTAEDIACEAE BRACKEN FAMILY Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn Bracken-Fern COF DRYOPTERIDACEAE TRUE FERN FAMILILY Athyrium filix-femina (L.) Roth ssp. angustum (Willd.) Northeastern Lady Fern FF Clausen Cystopteris bulbifera (L.) Bernh. Bulblet Fern FF Dryopteris carthusiana (Villars) H.P. Fuchs Spinulose Woodfern FF Matteuccia struthiopteris (L.) Tod. Ostrich Fern FF Onoclea sensibilis L. Sensitive Fern FF Polystichum acrostichoides (Michaux) Schott Christmas Fern FF ADDER’S-TONGUE- OPHIOGLOSSACEAE FERN FAMILY Botrychium virginianum (L.) Sw. Rattlesnake Fern FF FLOWERING FERN OSMUNDACEAE FAMILY Osmunda regalis L. Royal Fern WM POLYPODIACEAE POLYPODY FAMILY Polypodium virginianum L. Rock Polypody FF MAIDENHAIR FERN PTERIDACEAE FAMILY Adiantum pedatum L. ssp. pedatum Northern Maidenhair Fern FF THELYPTERIDACEAE MARSH FERN FAMILY Thelypteris palustris (Salisb.) Schott Marsh Fern WM LYCOPODIACEAE CLUB MOSS FAMILY Lycopodium lucidulum Michaux Shining Clubmoss OF Lycopodium tristachyum Pursh Ground-cedar COF SELAGINELLACEAE SPIKEMOSS FAMILY Selaginella apoda (L.) Fern. Spikemoss LRB CUPRESSACEAE CYPRESS FAMILY Juniperus communis L. Common Juniper Jun-E DS Juniperus virginiana L. Red Cedar Jun-E SD Thuja occidentalis L. White Cedar LRB PINACEAE PINE FAMILY Larix laricina (Duroi) K. Koch Tamarack Jun LRB Pinus banksiana Lambert Jack Pine COF Pinus resinosa Sol. ex Aiton Red Pine Jun-M CF Pinery Provincial Park Vascular Plant List 1 Pinery Provincial Park Vascular Plant List Flowering Latin Name Common Name Community Date Pinus strobus L. -

Brewing Beer with Native Plants (Seasonality)

BREWING BEER WITH INDIANA NATIVE PLANTS Proper plant identification is important. Many edible native plants have poisonous look-alikes! Availability/When to Harvest Spring. Summer. Fall Winter . Year-round . (note: some plants have more than one part that is edible, and depending on what is being harvested may determine when that harvesting period is) TREES The wood of many native trees (especially oak) can be used to age beer on, whether it be barrels or cuttings. Woods can also be used to smoke the beers/malts as well. Eastern Hemlock (Tsuga Canadensis): Needles and young twigs can be brewed into a tea or added as ingredients in cooking, similar flavoring to spruce. Tamarack (Larix laricina): Bark and twigs can be brewed into a tea with a green, earthy flavor. Pine species (Pinus strobus, Pinus banksiana, Pinus virginiana): all pine species have needles that can be made into tea, all similar flavor. Eastern Red Cedar (Juniperus virginiana): mature, dark blue berries and young twigs may be made into tea or cooked with, similar in flavor to most other evergreen species. Pawpaw (Asimina triloba): edible fruit, often described as a mango/banana flavor hybrid. Sassafras (Sassafras albidum): root used to make tea, formerly used to make rootbeer. Similarly flavored, but much more earthy and bitter. Leaves have a spicier, lemony taste and young leaves are sometimes used in salads. Leaves are also dried and included in file powder, common in Cajun and Creole cooking. Northern Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis): Ripe, purple-brown fruits are edible and sweet. Red Mulberry (Morus rubra): mature red-purple-black fruit is sweet and juicy. -

(Rosaceae), I. Differentiation of Mespilus and Crataegus

Phytotaxa 257 (3): 201–229 ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/pt/ PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2016 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.257.3.1 STUDIES IN MESPILUS, CRATAEGUS, AND ×CRATAEMESPILUS (ROSACEAE), I. DIFFERENTIATION OF MESPILUS AND CRATAEGUS, EXPANSION OF ×CRATAEMESPILUS, WITH SUPPLEMENTARY OBSERVATIONS ON DIFFERENCES BETWEEN THE CRATAEGUS AND AMELANCHIER CLADES JAMES B. PHIPPS Department of Biology, The University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario N6A 5B7, Canada; email: [email protected] Abstract The paper argues the position for retaining a monotypic Mespilus, i.e., in the sense of M. germanica, the medlar. Recent cladistic papers lend support for Mespilus being sister to Crataegus, and there is a clear morphological distinction from Cra- taegus, emphasized by adaptation to carnivore frugivory. Mespilus secured, the paper then treats each of the known hybrids between Mespilus and Crataegus, making the new combination Crataemespilus ×canescens (J.B. Phipps) J.B. Phipps. Keywords: Crataemespilus ×canescens (J.B. Phipps) J.B. Phipps comb. nov.; inflorescence position; medlar; Mespilus a folk-genus; Mespilus distinct from Crataegus; Rosaceae; taxonomic history of Mespilus Introduction The author has a long-standing interest in generic delimitation in the Maloid genera of the Rosaceae (Maleae Small, formerly Maloideae C. Weber, Pyrinae Dumort.), as shown particularly in a series of papers with K. Robertson, J. Rohrer, and P.G. Smith (Phipps et al. 1990, 1991; Robertson at al. 1991, 1992; Rohrer at al. 1991, 1994) which treated all 28 genera of Maleae as recognised by us. There is also a revisionary treatment of New World Heteromeles M.J.