Antarctica Exploration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Educator's Guide

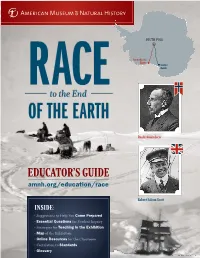

SOUTH POLE Amundsen’s Route Scott’s Route Roald Amundsen EDUCATOR’S GUIDE amnh.org/education/race Robert Falcon Scott INSIDE: • Suggestions to Help You Come Prepared • Essential Questions for Student Inquiry • Strategies for Teaching in the Exhibition • Map of the Exhibition • Online Resources for the Classroom • Correlation to Standards • Glossary ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS Who would be fi rst to set foot at the South Pole, Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen or British Naval offi cer Robert Falcon Scott? Tracing their heroic journeys, this exhibition portrays the harsh environment and scientifi c importance of the last continent to be explored. Use the Essential Questions below to connect the exhibition’s themes to your curriculum. What do explorers need to survive during What is Antarctica? Antarctica is Earth’s southernmost continent. About the size of the polar expeditions? United States and Mexico combined, it’s almost entirely covered Exploring Antarc- by a thick ice sheet that gives it the highest average elevation of tica involved great any continent. This ice sheet contains 90% of the world’s land ice, danger and un- which represents 70% of its fresh water. Antarctica is the coldest imaginable physical place on Earth, and an encircling polar ocean current keeps it hardship. Hazards that way. Winds blowing out of the continent’s core can reach included snow over 320 kilometers per hour (200 mph), making it the windiest. blindness, malnu- Since most of Antarctica receives no precipitation at all, it’s also trition, frostbite, the driest place on Earth. Its landforms include high plateaus and crevasses, and active volcanoes. -

We Look for Light Within

“We look for light from within”: Shackleton’s Indomitable Spirit “For scientific discovery, give me Scott; for speed and efficiency of travel, give me Amundsen; but when you are in a hopeless situation, when you are seeing no way out, get down on your knees and pray for Shackleton.” — Raymond Priestley Shackleton—his name defines the “Heroic Age of Antarctica Exploration.” Setting out to be the first to the South Pole and later the first to cross the frozen continent, Ernest Shackleton failed. Sent home early from Robert F. Scott’s Discovery expedition, seven years later turning back less than 100 miles from the South Pole to save his men from certain death, and then in 1914 suffering disaster at the start of the Endurance expedition as his ship was trapped and crushed by ice, he seems an unlikely hero whose deeds would endure to this day. But leadership, courage, wisdom, trust, empathy, and strength define the man. Shackleton’s spirit continues to inspire in the 100th year after the rescue of the Endurance crew from Elephant Island. This exhibit is a learning collaboration between the Rauner Special Collections Library and “Pole to Pole,” an environmental studies course taught by Ross Virginia examining climate change in the polar regions through the lens of history, exploration and science. Fifty-one Dartmouth students shared their research to produce this exhibit exploring Shackleton and the Antarctica of his time. Discovery: Keeping Spirits Afloat In 1901, the first British Antarctic expedition in sixty years commenced aboard the Discovery, a newly-constructed vessel designed specifically for this trip. -

Antarctic Primer

Antarctic Primer By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller Designed by: Olivia Young, Aurora Expeditions October 2018 Cover image © I.Tortosa Morgan Suite 12, Level 2 35 Buckingham Street Surry Hills, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia To anyone who goes to the Antarctic, there is a tremendous appeal, an unparalleled combination of grandeur, beauty, vastness, loneliness, and malevolence —all of which sound terribly melodramatic — but which truly convey the actual feeling of Antarctica. Where else in the world are all of these descriptions really true? —Captain T.L.M. Sunter, ‘The Antarctic Century Newsletter ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 3 CONTENTS I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Guidance for Visitors to the Antarctic Antarctica’s Historic Heritage South Georgia Biosecurity II. THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT Antarctica The Southern Ocean The Continent Climate Atmospheric Phenomena The Ozone Hole Climate Change Sea Ice The Antarctic Ice Cap Icebergs A Short Glossary of Ice Terms III. THE BIOLOGICAL ENVIRONMENT Life in Antarctica Adapting to the Cold The Kingdom of Krill IV. THE WILDLIFE Antarctic Squids Antarctic Fishes Antarctic Birds Antarctic Seals Antarctic Whales 4 AURORA EXPEDITIONS | Pioneering expedition travel to the heart of nature. CONTENTS V. EXPLORERS AND SCIENTISTS The Exploration of Antarctica The Antarctic Treaty VI. PLACES YOU MAY VISIT South Shetland Islands Antarctic Peninsula Weddell Sea South Orkney Islands South Georgia The Falkland Islands South Sandwich Islands The Historic Ross Sea Sector Commonwealth Bay VII. FURTHER READING VIII. WILDLIFE CHECKLISTS ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 5 Adélie penguins in the Antarctic Peninsula I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Antarctica is the largest wilderness area on earth, a place that must be preserved in its present, virtually pristine state. -

The Antarctic Contribution to Holocene Global Sea Level Rise

The Antarctic contribution to Holocene global sea level rise Olafur Ing6lfsson & Christian Hjort The Holocene glacial and climatic development in Antarctica differed considerably from that in the Northern Hemisphere. Initial deglaciation of inner shelf and adjacent land areas in Antarctica dates back to between 10-8 Kya, when most Northern Hemisphere ice sheets had already disappeared or diminished considerably. The continued deglaciation of currently ice-free land in Antarctica occurred gradually between ca. 8-5 Kya. A large southern portion of the marine-based Ross Ice Sheet disintegrated during this late deglaciation phase. Some currently ice-free areas were deglaciated as late as 3 Kya. Between 8-5 Kya, global glacio-eustatically driven sea level rose by 10-17 m, with 4-8 m of this increase occurring after 7 Kya. Since the Northern Hemisphere ice sheets had practically disappeared by 8-7 Kya, we suggest that Antarctic deglaciation caused a considerable part of the global sea level rise between 8-7 Kya, and most of it between 7-5 Kya. The global mid-Holocene sea level high stand, broadly dated to between 84Kya, and the Littorina-Tapes transgressions in Scandinavia and simultaneous transgressions recorded from sites e.g. in Svalbard and Greenland, dated to 7-5 Kya, probably reflect input of meltwater from the Antarctic deglaciation. 0. Ingcilfsson, Gotlienburg Universiw, Earth Sciences Centre. Box 460, SE-405 30 Goteborg, Sweden; C. Hjort, Dept. of Quaternary Geology, Lund University, Sdvegatan 13, SE-223 62 Lund, Sweden. Introduction dated to 20-17 Kya (thousands of years before present) in the western Ross Sea area (Stuiver et al. -

99-00 May No. 4

THE ANTARCTICAN SOCIETY 7338 Wayfarer Drive Fairfax Station, Virginia 22039 HONORARY PRESIDENT — MRS. PAUL A. SIPLE Vol. 99-00 May No. 4 Presidents: Dr. Carl R. Eklund, 1959-61 Dr. Paul A. Siple, 1961-62 Mr. Gordon D. Cartwright, 1962-63 BRASH ICE RADM David M. Tyree (Ret.), 1963-64 Mr. George R. Toney, 1964-65 Mr. Morton J. Rubin, 1965-66 Dr. Albert R Crary, 1966-68 As you can readily see, this newsletter is NOT announcing a speaker Dr. Henry M. Dater, 1968-70 program, as we have not lined anyone up, nor have any of you stepped Mr. George A. Doumani, 1970-71 Dr. William J. L. Sladen, 1971-73 forward announcing your availability. So we are just moving out with a Mr. Peter F. Bermel, 1973-75 Dr. Kenneth J. Bertrand, 1975-77 newsletter based on some facts, some fiction, some fabrications. It will be Mrs. Paul A. Siple, 1977-78 Dr. Paul C. Dalrymple, 1978-80 up to you to ascertain which ones are which. Good luck! Dr. Meredith F. Burrill, 1980-82 Dr. Mort D. Turner, 1982-84 Dr. Edward P. Todd, 1984-86 Two more Byrd men have been struck down -- Al Lindsey, the last of the Mr. Robert H. T. Dodson, 1986-88 Dr. Robert H. Rutford, 1988-90 Byrd scientists to die, and Steve Corey, Supply Officer, both of the 1933-35 Mr. Guy G. Guthridge, 1990-92 Byrd Antarctic Expedition. Al was a handsome man, and he and his wife, Dr. Polly A. Penhale, 1992-94 Mr. Tony K. Meunier, 1994-96 Elizabeth, were a stunning couple. -

Antarctica: Music, Sounds and Cultural Connections

Antarctica Music, sounds and cultural connections Antarctica Music, sounds and cultural connections Edited by Bernadette Hince, Rupert Summerson and Arnan Wiesel Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Antarctica - music, sounds and cultural connections / edited by Bernadette Hince, Rupert Summerson, Arnan Wiesel. ISBN: 9781925022285 (paperback) 9781925022292 (ebook) Subjects: Australasian Antarctic Expedition (1911-1914)--Centennial celebrations, etc. Music festivals--Australian Capital Territory--Canberra. Antarctica--Discovery and exploration--Australian--Congresses. Antarctica--Songs and music--Congresses. Other Creators/Contributors: Hince, B. (Bernadette), editor. Summerson, Rupert, editor. Wiesel, Arnan, editor. Australian National University School of Music. Antarctica - music, sounds and cultural connections (2011 : Australian National University). Dewey Number: 780.789471 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photo: Moonrise over Fram Bank, Antarctica. Photographer: Steve Nicol © Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2015 ANU Press Contents Preface: Music and Antarctica . ix Arnan Wiesel Introduction: Listening to Antarctica . 1 Tom Griffiths Mawson’s musings and Morse code: Antarctic silence at the end of the ‘Heroic Era’, and how it was lost . 15 Mark Pharaoh Thulia: a Tale of the Antarctic (1843): The earliest Antarctic poem and its musical setting . 23 Elizabeth Truswell Nankyoku no kyoku: The cultural life of the Shirase Antarctic Expedition 1910–12 . -

Sir Clements R. Markham 1830-1916

Sir Clements R. Markham 1830-1916 ‘BLUE PLAQUES’ adorn the houses of south polar explorers James Clark Ross, Robert Falcon Scott, Edward Adrian Wilson, Sir Ernest H. Shackleton, and, at one time, Captain Laurence Oates (his house was demolished and the plaque stored away). If Sir Clements Markham had not lived, it’s not unreasonable to think that of these only the one for Ross would exist today. Markham was the Britain’s great champion of polar exploration, particularly Antarctic exploration. Markham presided over the Sixth International Geographical Congress in 1895, meeting in London, and inserted the declaration that “the exploration of the Antarctic Regions is the greatest piece of geographical exploration still to be undertaken.” The world took notice and eyes were soon directed South. Markham’s great achievement was the National Antarctic Expedition (Discovery 1901-04) for which he chose Robert Falcon Scott as leader. He would have passed on both Wilson and Shackleton, too. When Scott contemplated heading South again, it was Markham who lent his expertise at planning, fundraising and ‘gentle arm-twisting.’ Without him, the British Antarctic Expedition (Terra Nova 1910-13) might not have been. As a young man Markham was in the Royal Navy on the Pacific station and went to the Arctic on Austin’s Franklin Search expedition of 1850-51. He served for many years in the India Office. In 1860 he was charged with collecting cinchona trees and seeds in the Andes for planting in India thus assuring a dependable supply of quinine. He accompanied Napier on the Abyssinian campaign and was present at the capture of Magdala. -

The Antarctic Treaty

The Antarctic Treaty Measures adopted at the Thirty-ninth Consultative Meeting held at Santiago, Chile 23 May – 1 June 2016 Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs by Command of Her Majesty November 2017 Cm 9542 © Crown copyright 2017 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at Treaty Section, Foreign and Commonwealth Office, King Charles Street, London, SW1A 2AH ISBN 978-1-5286-0126-9 CCS1117441642 11/17 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majestyʼs Stationery Office MEASURES ADOPTED AT THE THIRTY-NINTH ANTARCTIC TREATY CONSULTATIVE MEETING Santiago, Chile 23 May – 1 June 2016 The Measures1 adopted at the Thirty-ninth Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting are reproduced below from the Final Report of the Meeting. In accordance with Article IX, paragraph 4, of the Antarctic Treaty, the Measures adopted at Consultative Meetings become effective upon approval by all Contracting Parties whose representatives were entitled to participate in the meeting at which they were adopted (i.e. all the Consultative Parties). The full text of the Final Report of the Meeting, including the Decisions and Resolutions adopted at that Meeting and colour copies of the maps found in this command paper, is available on the website of the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat at www.ats.aq/documents. -

A History of Tourism, Leisure and Adventure in the Antarctic and Sub-Antarctic, C.1895 to Present

A History of Tourism, Leisure and Adventure in the Antarctic and Sub-Antarctic, c.1895 to Present by Wouter Pierre Hanekom Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of History in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof Sandra Scott Swart April 2014 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za Plagiarism Declaration By submitting this dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that the reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe on any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Signature: Date: Copyright © 2014 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract This thesis deals with the nature and historical development of tourism and leisure activities that have been conducted within the Antarctic and sub-Antarctic regions from 1895 to present. First, it traces the brief history of human involvement with the Antarctic continent, which culminated in a surge of ostensibly scientific exploration with jingoistic overtones which has become widely known as the ‘Heroic Age’ of Antarctic exploration. These explorers’ adventures, taken up by the popular press and promoted by jingoistic governments, popularised a particular conception of the continent to the point where people imagined going to see it for themselves, vicariously reliving their heroes’ adventures in the form of tourism. The rise of formal governance on the Antarctic is then traced and used to explain how this provided for regular tourist activities to commence since the mid-1960s. -

Scurvy? Is a Certain There Amount of Medical Sure, for Know That Sheds Light on These Questions

J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2013; 43:175–81 Paper http://dx.doi.org/10.4997/JRCPE.2013.217 © 2013 Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh The role of scurvy in Scott’s return from the South Pole AR Butler Honorary Professor of Medical Science, Medical School, University of St Andrews, Scotland, UK ABSTRACT Scurvy, caused by lack of vitamin C, was a major problem for polar Correspondence to AR Butler, explorers. It may have contributed to the general ill-health of the members of Purdie Building, University of St Andrews, Scott’s polar party in 1912 but their deaths are more likely to have been caused by St Andrews KY16 9ST, a combination of frostbite, malnutrition and hypothermia. Some have argued that Scotland, UK Oates’s war wound in particular suffered dehiscence caused by a lack of vitamin C, but there is little evidence to support this. At the time, many doctors in Britain tel. +44 (0)1334 474720 overlooked the results of the experiments by Axel Holst and Theodor Frølich e-mail [email protected] which showed the effects of nutritional deficiencies and continued to accept the view, championed by Sir Almroth Wright, that polar scurvy was due to ptomaine poisoning from tainted pemmican. Because of this, any advice given to Scott during his preparations would probably not have helped him minimise the effect of scurvy on the members of his party. KEYWORDS Polar exploration, scurvy, Robert Falcon Scott, Lawrence Oates DECLaratIONS OF INTERESTS No conflicts of interest declared. INTRODUCTION The year 2012 marked the centenary of Robert -

The Legal Regime of the Arctic Ocean

The Legal Regime of the Arctic Ocean Alexander Proelss*/Till Müller** I. Factual Background 653 II. The Legal Regime of the Arctic 654 1. Is There a General Legal Regime of the Arctic? 654 2. Status of and Passage through the North West Passage 655 a. The North West Passage as Historic Waters of Canada 656 b. Straight Baselines in the Arctic 658 c. The Right of Innocent Passage through the Arctic Straits 660 3. Arctic Continental Shelf Issues 661 a. Status of the Continental Shelf 661 b. Seaward Limit of the Continental Shelf 662 c. The Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf: Responsibilities and Recommendations 672 d. Future Prospects 682 4. Protection of the Arctic Environment 683 III. Conclusion 687 Many readers will have taken note of recent reports on the legal status of the Arctic Ocean in several international papers. For example, on 13 August 2007 the “Financial Times Deutschland” headlined, in a modification of a famous environ- mental slogan of the late 1970’s, “Save the North Pole!”,1 and the “Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung” had already asked on 3 August 2007 “Whose is the North Pole?”2 While the “Time Magazine” declared a “Fight for the Top of the World”,3 the “Times” predicted the beginning of a new mineral war.4 Some readers will also have followed the television coverage of two Russian mini-submarines reaching the sea-bed more than 4,000 m beneath the North Pole on 1 August 2007 and planting a one meter-high titanium Russian flag therein in an attempt to bolster the coun- try’s claim on the natural resources of the sea-bed and within the subsoil of the re- spective area. -

The Quest for the Northwest Passage, by James P. Delgado

REVIEWS • 323 learn the identity of what they have been reading up to that BRAY, E.F. de. 1992. A Frenchman in search of Franklin: De point. The document identified as HBCA E.37/3, which Bray’s Arctic journal, 1852–1854. Edited by William Barr. Barr, following Anderson, refers to as a full journal Toronto and Buffalo: University of Toronto Press. (p. 166, n.1), turns out to be what I would call Anderson’s PELLY, D. 1981. Expedition: An Arctic journey through history on field notes, written daily during the expedition. In con- George Back’s River. Toronto: Betelgeuse. trast, the document that Barr has referred to in footnotes as the “fair copy of Anderson’s journal” (HBCA B.200/a/ I.S. MacLaren 31), although based on those field notes, was written after Canadian Studies Program the expedition: it shows signs of revision and narrative Department of Political Science polish. Barr’s use of the term journal to refer to both University of Alberta documents is misleading, as it blurs that important distinc- Edmonton, Alberta, Canada tion. Furthermore, justification for subordinating Stewart’s T6G 2H4 journal (Provincial Archives of Alberta 74.1/137) to Anderson’s is rendered only implicitly: Stewart’s is “gen- erally less detailed than” Anderson’s (p. 166–167). One is ACROSS THE TOP OF THE WORLD: THE QUEST FOR left to infer that the editing accords with the chain of THE NORTHWEST PASSAGE. By JAMES P. DELGADO. command, Stewart being Anderson’s junior. None of these Vancouver and Toronto: Douglas & McIntyre, 1999.