T He Sp Lendour of the Middle Jo M on C Ulture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japan Geoscience Union Meeting 2009 Presentation List

Japan Geoscience Union Meeting 2009 Presentation List A002: (Advances in Earth & Planetary Science) oral 201A 5/17, 9:45–10:20, *A002-001, Science of small bodies opened by Hayabusa Akira Fujiwara 5/17, 10:20–10:55, *A002-002, What has the lunar explorer ''Kaguya'' seen ? Junichi Haruyama 5/17, 10:55–11:30, *A002-003, Planetary Explorations of Japan: Past, current, and future Takehiko Satoh A003: (Geoscience Education and Outreach) oral 301A 5/17, 9:00–9:02, Introductory talk -outreach activity for primary school students 5/17, 9:02–9:14, A003-001, Learning of geological formation for pupils by Geological Museum: Part (3) Explanation of geological formation Shiro Tamanyu, Rie Morijiri, Yuki Sawada 5/17, 9:14-9:26, A003-002 YUREO: an analog experiment equipment for earthquake induced landslide Youhei Suzuki, Shintaro Hayashi, Shuichi Sasaki 5/17, 9:26-9:38, A003-003 Learning of 'geological formation' for elementary schoolchildren by the Geological Museum, AIST: Overview and Drawing worksheets Rie Morijiri, Yuki Sawada, Shiro Tamanyu 5/17, 9:38-9:50, A003-004 Collaborative educational activities with schools in the Geological Museum and Geological Survey of Japan Yuki Sawada, Rie Morijiri, Shiro Tamanyu, other 5/17, 9:50-10:02, A003-005 What did the Schoolchildren's Summer Course in Seismology and Volcanology left 400 participants something? Kazuyuki Nakagawa 5/17, 10:02-10:14, A003-006 The seacret of Kyoto : The 9th Schoolchildren's Summer Course inSeismology and Volcanology Akiko Sato, Akira Sangawa, Kazuyuki Nakagawa Working group for -

Modelling Global Fresh Surface Water Temperature

Modelling global fresh surface water temperature Tessa Eikelboom MSc Thesis Physical Geography May 2010 Supervisors: Dr. L.P.H. van Beek and Prof. Dr. Ir. M.F.P. Bierkens Department of Physical Geography Faculty of Geosciences Utrecht University 1 ABSTRACT A change in fresh surface water temperature influences biological and chemical parameters such as oxygen and nutrient availability, but also has major effects on hydrological and physical processes which include transport, sediment concentration, ice formation and ice melt. The thermal profile of fresh surface waters depends on meteorological and morphological characteristics. Climate change influences the water and energy budget and thereby also the thermal structure of fresh surface waters. The oceans temperature is influenced by the inflow of rivers and streams. The variations in fresh surface water temperatures are only known for a scarce amount of long term temperature records. The understanding of changes in thermal processes by modelling the variations in temperature over time is therefore very useful to simulate the global effect of climate change on water temperatures. A physical based model was validated with regional daily and global monthly water temperature data of fresh surface water which includes both rivers and lakes. The basic assumption for the PCR‐GLOBWB model is the assumption that the fresh surface water temperature is the net result of all incoming en outgoing fluxes. The global hydrological model PCR‐GLOBWB contains a water and heat budget. The heat balance is solved using the following terms: short‐wave insolation, long‐wave atmospheric radiation, water‐surface backscatter, evaporation, air/water conduction and can be simplified into lateral and advective energy. -

Lake Suwa Mystery and Inspired the World-Renowned Avant-Garde Artist Taro Okamoto

142 Ueda, Saku Manji no sekibutsuSekibutsu Dokuzawa Kōsen (2km) (lit. Buddhist stone statue of Manji) A stone statue of Kiotoshizaka Slope (2.4km) Amitabha Buddha made in the Manji era (1658-1661). Discover Shimosuwa Yashima Wetland (18km) Minute The artist is said to be the same as the torii gate of Suigetsu Park Walking Map ( ) = transit time Harumiya. It's distinct facial feature is still largely a Enjoy the view of Lake Suwa mystery and inspired the world-renowned avant-garde artist Taro Okamoto. Jiun-ji Temple Dokuzawa Kōsen Ukishima-sha shrine A temple protected was known as Stone Monument of Taro Okamoto by the warlord Visit Suwa Grand Shrines (lit. shrine on the floating island) Tenkei no Matsu “Shingen’s secret Shingen Takeda. 99min The shrine on a sandbar that never sink, (lit. Tenkei's pine tree) hot spring”, where Sankaku Batchō one of the seven mysteries of Shimosuwa. A Pine tree planted by injured soldiers A standard course full of the town's historic sights. Sankaku Batchō is the the 16th century Zen bathed to heal Hot Springs monk Tenkei. their wounds. SHIMOSUWA triangle formed by Akimiya, Harumiya and Ōtōrō with the side length 872.72m. The baths of Shimosuwa’s quaint ryokan and Akimiya (15 min) → Fushimiya-tei (10 min) → Harumiya / Manji no Sekibutsu its many enjoyable public bathhouses are Enjoy the atmosphere walking around the ancient seat of the shrines of Suwa Taisha! (9 min) → Gebabashi / Ōtōrō (15min) → Sagara-zuka (25 min) → Akimiya (20min) Ochadokoro sourced from local natural hot springs! Hanamusubi Suwa-taishaSuwa Taisha Stone Stairway Welcoming merchants, travellers and visitors to the shrines of Suwa Taisha, Shimosuwa lourished in the Edo period Café Mind Soothing Harumiya 126 steps as the only post town with hot spring in Nakasendo, a highway which connects Edo (Tokyo) and Kyoto. -

A Synopsis of the Parasites from Cyprinid Fishes of the Genus Tribolodon in Japan (1908-2013)

生物圏科学 Biosphere Sci. 52:87-115 (2013) A synopsis of the parasites from cyprinid fishes of the genus Tribolodon in Japan (1908-2013) Kazuya Nagasawa and Hirotaka Katahira Graduate School of Biosphere Science, Hiroshima University Published by The Graduate School of Biosphere Science Hiroshima University Higashi-Hiroshima 739-8528, Japan December 2013 生物圏科学 Biosphere Sci. 52:87-115 (2013) REVIEW A synopsis of the parasites from cyprinid fishes of the genus Tribolodon in Japan (1908-2013) Kazuya Nagasawa1)* and Hirotaka Katahira1,2) 1) Graduate School of Biosphere Science, Hiroshima University, 1-4-4 Kagamiyama, Higashi-Hiroshima, Hiroshima 739-8528, Japan 2) Present address: Graduate School of Environmental Science, Hokkaido University, N10 W5, Sapporo, Hokkaido 060-0810, Japan Abstract Four species of the cyprinid genus Tribolodon occur in Japan: big-scaled redfin T. hakonensis, Sakhalin redfin T. sachalinensis, Pacific redfin T. brandtii, and long-jawed redfin T. nakamuraii. Of these species, T. hakonensis is widely distributed in Japan and is important in commercial and recreational fisheries. Two species, T. hakonensis and T. brandtii, exhibit anadromy. In this paper, information on the protistan and metazoan parasites of the four species of Tribolodon in Japan is compiled based on the literature published for 106 years between 1908 and 2013, and the parasites, including 44 named species and those not identified to species level, are listed by higher taxon as follows: Ciliophora (2 named species), Myxozoa (1), Trematoda (18), Monogenea (0), Cestoda (3), Nematoda (9), Acanthocephala (2), Hirudinida (1), Mollusca (1), Branchiura (0), Copepoda (6 ), and Isopoda (1). For each taxon of parasite, the following information is given: its currently recognized scientific name, previous identification used for the parasite occurring in or on Tribolodon spp.; habitat (freshwater, brackish, or marine); site(s) of infection within or on the host; known geographical distribution in Japan; and the published source of each locality record. -

Estimation of Sources and Inflow of Dioxins and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons from the Sediment Core of Lake Suwa, Japan

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Shinshu University Institutional Repository Estimation of sources and inflow of Dioxins and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons from the sediment core of Lake Suwa, Japan Author names Yoshinori Ikenaka 1, Heesoo Eun 2, Eiki Watanabe 2, Fujio Kumon 3, Yuichi Miyabara 1 Author affiliations 1 Research and Education Center for Inlandwater Environment, Shinshu University, 5-2-4 Kogandori, Suwa, Nagano 392-0027, Japan, 2 National Institute for Agro-Environmental Sciences, 3-1-3, Kannondai, Tukuba, Ibaraki 305-8604, Japan, 3 Department of Environmental Science, Faculty of Sciences, Shinshu University, 3-1-1, Asahi, Matzumoto, Nagano 390-8621, Japan Corresponding author Yoshinori Ikenaka Research and Education Center for Inlandwater Environment, Shinshu University, 5-2-4 Kogandori, Suwa, Nagano 392-0027, Japan. Telephone numbers: +81-266-52-1955. Fax number: +81-266-57-1341. E-mail addresses: [email protected] Author:Ikenaka, Y; Eun, H; Watanabe, E; Kumon, F; Miyabara, Y Title:Estimation of sources and inflow of dioxins and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from the sediment core of Lake Suwa, Japan Journal:ENVIRONMENTAL POLLUTION Vol:138 No.:3 Page:529-537 Year:2005 1 Abstract To elucidate the historical changes in polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxin (PCDD), polychlorinated dibenzofuran (PCDF), coplanar polychlorinated biphenyl (co-PCB), and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) inflows in Lake Suwa, their concentrations in the sediment core were analyzed in 5 cm interval. The maximum concentrations (depth cm) of PCDDs/DFs, co-PCBs, and PAHs were 25.2 ng/g dry (30-35 cm), 19.0 ng/g dry (30-35 cm), and 738, 795 ng/g dry (50-55 cm, 30-35 cm), respectively. -

S魍量馳欝踵魂c躍髄膿c⑪齪鯉鶴諭re麗璽電s甑騒職磯電§鶴聡翻

Bullet孟n ofthe Geological Survey ofJapan,voL34(7〉,P・361~3821983 543.4 546.22十546.26(551.79) S魍量馳欝踵魂C躍髄膿C⑪齪鯉鶴諭Re麗璽電S甑騒職磯電§鶴聡翻 丁恥、総量躍R⑱臨寵量⑪聡電⑪s㊧戯館騰聰慮麗欝y E聡w置欝⑪聡灘融聡電§ SHIGERu TERAsHIMA*,HIRosHI YoNETANI*, EIJI MATsuMoTo**and YosHlo INoucH:1** TERAsHIMA,Shigeru,YoNETANI,Hiroshi,MATsuMoTo,E茸iandINoucHI,Yoshio(1983)Sulhr and carbon contents in recentsediments and their relation to sedimentary environments, βz6JJ。σ60」。S%7∂.」ψαn,voL34(7),P.361-382。 Aあ舘臨c宣3Two hundred and sixty-seven samples ofRecent sediments were analyzed fbr total sulfじr,total carbon and organic carbon in order to examine their relationship to sedimentary environments.These samples were collected f士om the dif驚rent environment,i.e.,regions of nine lakes and six sea areas around the Japanese islands。Average content oftotalsulfhr in丘esh- water sediments is lower than that of both br批ckish and marine sediments in reduced condi. tion.However,there is no clear di伍erence oftotal sul釦r contents betweensediments ofmarine bays of ra her oxid五zed conditions and those ofthe eutrophic丘esh-water1乱kes。The contents oforganic carbon are higher in lake sediments than those ofmarine ones,whereas thoseofthe carbonate-carbon are more abundant in marine sediments than in lacust血e ones.As fbr the chemical fbrm ofsulfαr,50%or more of the total su1釦r existed in the fbrm ofsu1且de except in deep.seasediments which sulfide-sulfhr wasnot detected,A close positive correlation between total sulfαr and organic carbon contents appeared only in the sediments deposited under rather oxidized conditions in most -

Profundal Oligochaete Faunas (Annelida, Clitellata) in Japanese Lakes

Zoosymposia 9: 024–035 (2014) ISSN 1178-9905 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zoosymposia/ ZOOSYMPOSIA Copyright © 2014 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1178-9913 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zoosymposia.9.1.7 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:87CE37D4-408C-4750-8D7D-B87ADE6FACA9 Profundal oligochaete faunas (Annelida, Clitellata) in Japanese lakes AKIFUMI OHTAKA Faculty of Education, Hirosaki University, Hirosaki 036-8560, Japan. Email: [email protected] Abstract Thirty-eight species of oligochaetes (Annelida, Clitellata) belonging to five families were recorded from profundal bottoms of 50 freshwater lakes on Japanese islands. They were mostly widely distributed species, and the composition of fauna is basically explained by the scheme of Timm (2012), with parallel replacement of European species. Oxygen, temperature and surrounding fauna could be main factors determining the profundal fauna in the lakes. The lumbriculids (Styloscolex japonicus, Yamaguchia toyensis and Lumbriculus variegatus), haplotaxids (Haplotaxis gordioides) and enchytraeids (Marionina klaskisharum) were restricted to several deep and oligotrophic lakes located in Hokkaido and northern Honshu, where Rhyacodrilus komarovi often accompanied them. Limnodrilus hoffmeisteri was the commonest species, occurring irrespective of the trophic status and bottom temperature of the lake. Tubifex tubifex also occurred in wide trophic scale, but it has never been found in shallow eutrophic lakes where the bottom temperature exceeds 15°C, where L. hoffmeisteri, -

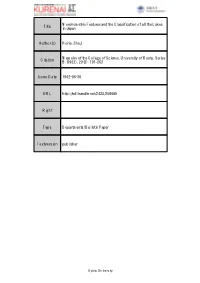

Title Morphometric Features and the Classification of All the Lakes In

Morphometric Features and the Classification of all the Lakes Title in Japan Author(s) Horie, Shoji Memoirs of the College of Science, University of Kyoto. Series Citation B (1962), 29(3): 191-262 Issue Date 1962-06-30 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/258665 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University MEMOIRS OF THE COLLEGE OI? SCIENCE, UNIVERSITY oF 1<YOTO, SERIES B, Vol. XXIX, No. 3, Article 2 (Biology), 1962 Morphome'tric Features and the Classification of all the Lal<es in Japan By Sh6ji HoRIE Otsu Hydrobio}ogical Station, Universi.ty of Kyoto (Osbom Zoological Laboratory, Yale ILJniversity) (Received MarÅëh 20, 1962) !ntroduetien The Japanese IslaRds which consist of four main parts, narnely Hol<kaido, Honshu, Shikoku and Kyushu, stretck from approximately 460N to 240N along tke easterR margin of the Ellrasiatic continent. Geologically speaking, this part of the globe is on.e of typically unstable crust, hence the Japanese often ex- perience severe earthquakes. Besides, the western part of the Peri-Pacific Volcanic Zone runs from the KamÅëhatka Peninsula via the Kuriles, Hokkaido, Honsltu, Kyushu, Ryukyu and to the Phillipine Is}ands. Both the presence of the eartltquake zone and severe vulcanism, together with the steep slopes of the mountains wkich occupy almost all of the country, have resulted in many lakes and ponds in the Japanese Islands. The total numbey of them is about 600 ln this small in.".u}ar country, which is almost equal in area to the State Montana of the United States. They are, moreover, not only numerous but sorae are very important Iakes from the viewpoint of both limnology and geology. -

Nature Buckwheat Noodles そば : SOBA Japan Central Honshu Visitors Can Enjoy the 4 Seasons of Nature Beauty

Nature Buckwheat Noodles そば : SOBA Japan Central Honshu Visitors can enjoy the 4 seasons of nature beauty. Typical local cuisine of Suwa. There is a local shop where tourists can enjoy traditionally handmade Nagano’s largest lake called Lake Suwa, soba noodles. Shimosuwa Kirigamine Plateau with gigantic view, Spring World’s rare plants at Yashima Wetland etc. Eel うなぎ : UNAGI Sakura festival (middle of the April) Travel Guide Eel shing was popular in Suwa because abundance Walk the downtown Spring festival of eels which used to inhabit in Lake Suwa. Eel is still (end of the April) a popular cuisine around Suwa area. Summer Ofune festival (31.July and 1.August) River Fish Cuisine 川魚料理 : KAWAUO SHINSYU Even though there is no ocean, Suwa is blessed with Lake Suwa reworks festival (15.August) lake and rivers. Hence, carp, crucian carp and pond Autumn smelt etc are popular ingredients in Suwa. There are SHIMOSUWA various ways of cooking such as Tempura, Fry and National new reworks competition Kanroni( food stewed in soy sauce and sugar)etc. (September) SOBA UNAGI Suwako marathon (October) Sashimi of Horse meet 馬刺し : BASASHI Walk the downtown autumn festival As Suwa used to be a horse breeding center, horse (November) meat are popular ingredients for Suwa people. Because of the beautiful color of meat, Basashi is Winter called Sakuraniku(Cherry blossom meet). Sukiyaki Wakasagi smelt shing (November to March ) style is also recommended. Coming ying of the swan to Lake Suwa KAWAUO BASASHI (January to February) Local Sake 地酒 : JIZAKE DATA 2014 Suwa is famous for delicious sake because of the Weather Data good quality of rice, water and skilled master brew- Annual Mean temperature : 11.0°C/51.8°F ers. -

霞ヶ浦ake Kasumigaura

3 The present conditions and eutrophication measures in lakes in Japan There are many designated lakes as well as other lakes in this country, but the closed nature (retention time), water depth, water temperature and catchment area load vary. Therefore, the eutrophication characteristics in lakes also vary as do opinions on the measures for tackling the problem. In this chapter, based on these points mentioned above, the present conditions of eutrophication in lakes in this country are described. For each lake, (1) the characteristics of catchment areas, (2) the water quality in lakes, the characteristics of biota, (3) the problems of the present situation and prospects for measures are described. 3-1 Lake Kasumigaura 3-1-1 Characteristics of the catchment area/lake Lake Kasumigaura is an inland sea-lake belonging to the Tonegawa River system that flows through the Kanto Plain, and the lake is situated on the left bank of the lower reaches of the Tonegawa River, a low-lying area in the southeast part of Ibaraki prefecture. The water area is about 220 km2, so it has the second largest area after Lake Biwa in this country. Moreover, the pondage is about 850 million m3, which is larger than the total pondage of the multipurpose dam that was constructed in the upper reaches of the Tonegawa River. About six thousand years ago, Lake Kasumigaura was part of the inlet connected to the present upper reaches of the Tonegawa River, Lake Inba and Lake Tega. Over the centuries, the mouth of the river became blocked by earth and sand that was carried from the upper reaches, and it is said that the lake more or less assumed its present shape about 1,500-2,000 years ago, becoming a freshwater lake around 1638 during the Edo period. -

Nagano Suwa Area Industrial Messe

NAGANO SUWA AREA INDUSTRIAL MESSE NAGANO-SUWA “Smart Devices Supply Base” and “International Creative Solution Base” Held in Suwa again in 2012! Technology from Suwa changes the world This year will be held on November Admission 9:30-15:30 (9:30-15:00 on Saturday) Free (visitors are issued IDs at entrance reception). Please present two business cards at the reception. Place Suwa Lake side, Suwa Lake Event Hall (Toyo Valve Co., Ltd. Suwa Plant, Old factory site) Contact Suwa Area Industrial Messe EXCO Office Address : 14-7 Kowata-minami, Suwa, Nagano 392-0023 (NPO Suwa Region Monozukuri Promotion Organization) Tel: +81-266-54-2588 Fax: +81-266-54-5133 E-mail: [email protected] Organizer : Executive Committee for the Suwa Area Industrial Messe 2012 [Constituent bodies] Okaya City, Suwa City, Chino City, Shimosuwa Town, Fujimi Town, Hara Village, Okaya Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Suwa Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Chino Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Shimosuwa Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Fujimi Society of Commerce and Industry, Hara Society of Commerce and Industry, Nagano Prefecture,Small Business Information Center of Nagano Prefecture, Nagano Techno Foundation Suwa Techno Lake Side Regional Center, Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO) Nagano Trade Informa- tion Center, Nagano Employers' Association, Nagano Prefectural Federation of Small Business Associations, Development Bank of Japan Inc., Hachijuni Bank, Ltd., Suwa Shinkin Bank Administrator : NPO Suwa Region Monozukuri Promotion Organization Special co-organizer : The Shinano Mainichi Shimbun Inc. Co-organizer : Nagano Nippo Co., Ltd. Special sponsors : Kitz Corporation, Kyocera Corporation, Seiko Epson Corporation, Teikoku Piston Ring Co., Ltd. -

From Freshwater Fishes in Japan

FOLIA PARASITOLOGICA 48: 275-288, 2001 Caryophyllidean tapeworms (Platyhelminthes: Eucestoda) from freshwater fishes in Japan Tomáš Scholz1, Takeshi Shimazu2, Peter D. Olson3 and Kazuya Nagasawa4 1Institute of Parasitology, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Branišovská 31, 370 05 České Budějovice, Czech Republic; 2Nagano Prefectural College, 8-49-7 Miwa, Nagano 380-8525, Japan; 3Department of Zoology, The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UK; 4National Research Institute of Far Seas Fisheries, 5-7-1 Orido, Shimizu-shi, Shizuoka 424-8633, Japan Key words: Cestoda, Caryophyllidea, Japan, taxonomy, morphology, zoogeography Abstract. The following caryophyllidean tapeworms were found in freshwater fishes from Japan (species reported from Japan for the first time marked with an asterisk): family Caryophyllaeidae: Paracaryophyllaeus gotoi (Motomura, 1927) from Misgurnus anguillicaudatus (Cantor); Archigetes sieboldi Leuckart, 1878 from Pseudorasbora parva (Temminck et Schlegel) and Sarcocheilichthys variegatus microoculus Mori (new hosts); family Lytocestidae: *Caryophyllaeides ergensi Scholz, 1990 from Tribolodon hakuensis (Günther), T. ezoe Okada et Ikeda, Hemibarbus barbus (Temminck et Schlegel) and Chaenogobius sp. (new hosts); Khawia japonensis (Yamaguti, 1934) from Cyprinus carpio Linnaeus; K. sinensis Hsü, 1935 from H. barbus (new host) and C. carpio; *K. parva (Zmeev, 1936) from Carassius auratus langsdorfii Valenciennes in Cuvier et Valenciennes and Carassius sp. (new hosts); and *Atractolytocestus sagittatus (Kulakovskaya et Akhmerov, 1962) from C. carpio; family Capingentidae: *Breviscolex orientalis Kulakovskaya, 1962 from H. barbus (new host); and Caryophyllidea gen. sp. (probably Breviscolex orientalis) from C. carpio. The validity of C. ergensi, originally described from Leuciscus leuciscus baicalensis from Mongolia, is confirmed on the basis of an evaluation of extensive material from Japan.