Monetary History of Medieval Courland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Health Systems in Transition

61575 Latvia HiT_2_WEB.pdf 1 03/03/2020 09:55 Vol. 21 No. 4 2019 Vol. Health Systems in Transition Vol. 21 No. 4 2019 Health Systems in Transition: in Transition: Health Systems C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Latvia Latvia Health system review Daiga Behmane Alina Dudele Anita Villerusa Janis Misins The Observatory is a partnership, hosted by WHO/Europe, which includes other international organizations (the European Commission, the World Bank); national and regional governments (Austria, Belgium, Finland, Kristine Klavina Ireland, Norway, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the Veneto Region of Italy); other health system organizations (the French National Union of Health Insurance Funds (UNCAM), the Dzintars Mozgis Health Foundation); and academia (the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) and the Giada Scarpetti London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM)). The Observatory has a secretariat in Brussels and it has hubs in London at LSE and LSHTM) and at the Berlin University of Technology. HiTs are in-depth profiles of health systems and policies, produced using a standardized approach that allows comparison across countries. They provide facts, figures and analysis and highlight reform initiatives in progress. Print ISSN 1817-6119 Web ISSN 1817-6127 61575 Latvia HiT_2_WEB.pdf 2 03/03/2020 09:55 Giada Scarpetti (Editor), and Ewout van Ginneken (Series editor) were responsible for this HiT Editorial Board Series editors Reinhard Busse, Berlin University of Technology, Germany Josep Figueras, European -

Atlantic Salmon (Salmo Salar ) in Subdivisions 22–31 (Baltic

ICES Advice on fishing opportunities, catch, and effort Baltic Sea ecoregion Published 29 May 2020 Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) in subdivisions 22–31 (Baltic Sea, excluding the Gulf of Finland) ICES advice on fishing opportunities ICES advises that when the precautionary approach is applied, total commercial sea catch in 2021 should be no more than 116 000 salmon, assuming no change in recreational effort. Applying the same catch proportions estimated from observations in the 2019 fishery, the catch in 2021 would be split as follows: 106 000 salmon projected landings (91%; i.e. 83% reported, 7% unreported, and 1% misreported) and projected discards of 10 000 salmon (9%; previously referred to as discards). This would correspond to commercial landings (the reported projected landings) of 96 600 salmon. ICES advises that management of salmon fisheries should be based on the status of individual river stocks. Fisheries on mixed stocks that encompass weak wild stocks present particular threats, and should be kept as close to zero as possible. Fisheries in open-sea areas or in coastal waters target mixed stocks; they are thus more likely to pose a threat to depleted stocks than fisheries in estuaries and in healthy (at or above MSY) wild or reared salmon rivers. The salmon stocks of rivers Rickleån, Sävarån, Öreälven, and Lögdeälven in the Gulf of Bothnia, Emån in southern Sweden, and all rivers in the southeastern Main Basin (AU 5) are particularly weak, and several have shown limited recovery to previous reductions in exploitation rates at sea. The offshore and coastal fisheries in the Main Basin includes catches from all of these weak salmon stocks on their feeding migration. -

East Baltic Vikings - with Particular Consideration to the Ctrronians

East Baltic Vikings - with particular consideration to the Ctrronians Swedish Allies in the Saga World EAST BALTIC At the mythical battlefield of Bravellir (Sw. VIKINGS - WITH Bnl.vallama), Danes and the Swedes clashed in a PARTICULAR fight of epic dimensions. The over-aged Danish king Harald Hildetand finally lost his life, and CONSIDERA his nephew king Sigurdr hringr won Denmark TION TO THE for the Swedes. The story appears in a fragment CURONIANS of a Norse saga from around 1300. But since Sa xo Grammaticus tells it, the written tradition Nils Blornkvist must go back at least to the late 12th century. Wri ting in Latin he prefers to call it bellum Suetici, 'the Swedish war'. It's for several reasons ob vious that Saxo has built his text on a Norse text that must have been quite similar to the preser ved fragment. The battle of Bravellir- the Norse fragment claims - was noteworthy in ancient tales for having be en the greatest, the hardest and the most even and uncertain of the wars that had been fought in the Nordic countries.1 Both sources give long lists of the famous heroes that joined the two armies in a way that recalls the list of ships in Homer's Iliad. These champions are the knight errants of Germanic epics, to some degree rela ted with those of chansons de geste. They are pre sented with characteristic epithets and eponyms that point out their origins in a town, a tribe or a country. When summed up they communicate a geographic vision of the northern World in the 11 th and 12th centuries. -

A Look at Schillings of the Free Imperial City of Riga by Charles Calkins

A Look at Schillings of the Free Imperial City of Riga by Charles Calkins The seaport of Riga is the capital of Latvia and the largest city of the Balkan states. It is located on the Gulf of Riga, a bay of the Baltic Sea, at the mouth of the Daugava river. The area was settled in ancient times by the Livs, a Finnic tribe, giving the area its name of Livonia. Riga began developing economically due to the Daugava being used as a Viking trade route to Byzantium. By the 12th century, German traders were visiting Riga, establishing an outpost near Riga in 1158. After a failed attempt at Christianization in the late 1100s, Bishop Albert landed with a force of crusaders in 1200, and transferred the Livonian bishopric to Riga in 1201, which became the Archbishopric of Riga in 1255. Albert established the Order of Livonian Brothers of the Sword in 1202 to defend territory and commerce, and Emperor Philip of Swabia caused Livonia to become a principality of the Holy Roman Empire. The Order of Livonian Brothers was given one-third of Livonia, and the Church the other two-thirds, which included Riga. In 1211, Riga minted its first coinage, and gradually gained more independence through the 1200s. In 1236, the Order of Livonian Brothers was defeated in battle with the Samogitians of Lithuania. The remaining Brothers were incorporated into the Teutonic Knights as a branch known as the Livonian Order. The Livonian Order subsequently gained control of Livonia. In 1282, Riga became a member of the Hanseatic League, a confederation of towns and merchant guilds which provided legal and military protection. -

Latvia Toponymic Factfile

TOPONYMIC FACT FILE Latvia Country name Latvia State title Republic of Latvia Name of citizen Latvian Official language Latvian (lv) Country name in official language Latvija State title in official language Latvijas Republika Script Roman n/a. Latvian uses the Roman alphabet with three Romanization System diacritics (see page 3). ISO-3166 country code (alpha-2/alpha-3) LV / LVA Capital (English conventional) Riga1 Capital in official language Rīga Population 1.88 million2 Introduction Latvia is the central of the three Baltic States3 in north-eastern Europe on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. It has existed as an independent state c.1918 to 1940 and again since 1990. In size it is similar to Sri Lanka or Sierra Leone. Latvia is approximately 1% smaller than neighbouring Lithuania, but has only two-thirds the population, estimated at 1.88 million in 20202. The population has been falling steadily since a high of 2,660,000 in 1989 source: Eurostat). Geographical names policy Latvian is written in Roman script. PCGN recommends using place names as found on official Latvian-language sources, retaining all diacritical marks. Latvian generic terms frequently appear with lower-case initial letters, and PCGN recommends reflecting this style. Allocation and recording of geographical names in Latvia are the responsibility of the Latvia Geospatial Information Agency (Latvian: Latvijas Ģeotelpiskās informācijas aģentūra – LGIA) which is part of the Ministry of Defence (Aizsardzības ministrija). The geographical names database on the LGIA website: http://map.lgia.gov.lv/index.php?lang=2&cPath=3&txt_id=24 is a useful official source for names. -

From Tribe to Nation a Brief History of Latvia

From Tribe to Nation A Brief History of Latvia 1 Cover photo: Popular People of Latvia are very proud of their history. It demonstration on is a history of the birth and development of the Dome Square, 1989 idea of an independent nation, and a consequent struggle to attain it, maintain it, and renew it. Above: A Zeppelin above Rīga in 1930 Albeit important, Latvian history is not entirely unique. The changes which swept through the ter- Below: Participants ritory of Latvia over the last two dozen centuries of the XXV Nationwide were tied to the ever changing map of Europe, Song and Dance and the shifting balance of power. From the Viking Celebration in 2013 conquests and German Crusades, to the recent World Wars, the territory of Latvia, strategically lo- cated on the Baltic Sea between the Scandinavian region and Russia, was very much part of these events, and shared their impact especially closely with its Baltic neighbours. What is unique and also attests to the importance of history in Latvia today, is how the growth and development of a nation, initially as a mere idea, permeated all these events through the centuries up to Latvian independence in 1918. In this brief history of Latvia you can read how Latvia grew from tribe to nation, how its history intertwined with changes throughout Europe, and how through them, or perhaps despite them, Lat- via came to be a country with such a proud and distinct national identity 2 1 3 Incredible Historical Landmarks Left: People of The Baltic Way – this was one of the most crea- Latvia united in the tive non-violent protest activities in history. -

The Baltics EU/Schengen Zone Baltic Tourist Map Traveling Between

The Baltics Development Fund Development EU/Schengen Zone Regional European European in your future your in g Investin n Unio European Lithuanian State Department of Tourism under the Ministry of Economy, 2019 Economy, of Ministry the under Tourism of Department State Lithuanian Tampere Investment and Development Agency of Latvia, of Agency Development and Investment Pori © Estonian Tourist Board / Enterprise Estonia, Enterprise / Board Tourist Estonian © FINL AND Vyborg Turku HELSINKI Estonia Latvia Lithuania Gulf of Finland St. Petersburg Estonia is just a little bigger than Denmark, Switzerland or the Latvia is best known for is Art Nouveau. The cultural and historic From Vilnius and its mysterious Baroque longing to Kaunas renowned Netherlands. Culturally, it is located at the crossroads of Northern, heritage of Latvian architecture spans many centuries, from authentic for its modernist buildings, from Trakai dating back to glorious Western and Eastern Europe. The first signs of human habitation in rural homesteads to unique samples of wooden architecture, to medieval Lithuania to the only port city Klaipėda and the Curonian TALLINN Novgorod Estonia trace back for nearly 10,000 years, which means Estonians luxurious palaces and manors, churches, and impressive Art Nouveau Spit – every place of Lithuania stands out for its unique way of Orebro STOCKHOLM Lake Peipus have been living continuously in one area for a longer period than buildings. Capital city Riga alone is home to over 700 buildings built in rendering the colorful nature and history of the country. Rivers and lakes of pure spring waters, forests of countless shades of green, many other nations in Europe. -

Saules Zemes Turtai EN(6).Pdf

3 SEVEN WONDERS OF THE LAND OF ŠIAULIAI THE HILL OF CROSSES with over 200,000 crosses. Every year, the hill is visited by thousands of tourists from all over the world. SUNDIAL SQUARE with the highest sundial in Lithuania and a gilded sculpture “Šaulys” (“Archer”) that has become the city’s symbol. THE ENSEMBLE OF TYTUVĖNAI CHURCH AND MONASTERY – one of the most interesting and largest examples of Lithuanian sacral architecture, adorned with frescoes, dating back to the 17th-18th centuries. THE BUTTERFLY EXPOSITION – you will find the largest collection of diurnal butterflies in Lithuania in the Akmenė Regional Museum. CHERRIES OF ŽAGARĖ – a four-day cherry festival and the election of the most beautiful scarecrow in one of the most unique Lithuanian towns in Joniškis land. WINDMILLS OF PAKRUOJIS – the wind accelerating in wide plains is turning the vanes of as many as 18 windmills. THE TULIP FLOWERING FESTIVAL – held every spring in the Burbiškis manor, Radviliškis land; as many as half a thousand tulip species burst into flower. 4 4 ŠIAULIAI The centre of the city, which was twice destroyed during the wars of the 20th century and rebuilt again, has distinct architectural heritage of the interwar pe- riod modernism, which has survived to this day. Šiauliai is a city-phoenix, every time rising from ashes. Discover Šiauliai and experience the magic of 3 “S”: sweets, special museums, and the sun. The symbols of the sun, scattered all over the city (sundials, stained glass, etc.), have become an integral part of the city. The oldest sweet factory of Lithuania, “Rūta”, operating for over 100 years, special museums of chocolate, photogra- phy, telephony, and the only such Vanda Kavaliauskienė’s Cats Museum with over 4000 exhibits. -

Ancient Natural Sacred Sites in Kurzeme Region, Latvia

dating back to 1234 about enfeoffing of 25 acres of land 5 to the Riga St. Peter’s Church, was situated. The hill fort IN THE WAKE OF THE CURONIANS was located in the Curonian land of Vanema. The Mežīte Hill Fort was constructed on a solitary, about 13 m high Longer distances of the route are hill, the slopes of which had been artificially made steep- heading along asphalt roads, but 3 The CURONIAN HILL FORT er. Its plateau is of a triangular form, 55 x 30–50 m large, access to ancient cult sites mostly is OF VeCKULDīGA with a narrower southern part, on which a 3 meters high available along gravel and forest roads. Kuldīga 56º59’664 21º57’688 rampart had been heaped up. It used to protect the as- Long before the introduction of Christianity in cent to the hill fort, which, just like in many other Latvian Length of the route 145 km the ancient land of Cursa and expansion of the hill forts, was planned in such a way that when invaders 9 10 22 Livonian Order, on the present site of the hill fort of were striving to conquer the hill fort, their shoulders, Veckuldīga, at the significant waterway of the Venta unprotected by a shield, would be turned against the 21 has been observed: in the nearby trees, there have ancestors’ traditions are still kept alive by celebrating cult tree, its age could be around 400–500 years. River, one of the largest and best fortified castles of hill fort’s defenders. -

Application Form for Listing Under the “European Heritage Label” Scheme

Application form for listing under the “European Heritage Label” scheme Country Latvia Region/province Kurzeme region, Kuldiga city Name of the cultural property1, monument, natural or urban site2, Kuldiga or site that has played a key role in European history. Owner the cultural property, Kuldiga Municipality monument, natural or urban site, or site that has played a key role in European history Public or private authorities Kuldiga Town Council responsible for the site or property (delegated management) Postal address Geographic coordinates Geographical location: Latitude 56°58’03’’; Longitude 21°58’14’’ The property is located in the western part of Latvia, in Kuldiga district, 150 km from Riga, the capital of Latvia. See attached map – appendix nr. 1. Reasons for listing Kuldiga is a little unique old town, which is significant for Preserved town planning of middle age style; Preserved splendid wooden buildings of 17-19 centuries; There is the widest waterfall in all the Europe situated (the width is 249 - 275 m depending from season); The coasts of the riversides are linked with old, one of the longest brick bridges; Since 1368 Kuldiga has been a member of the Hanseatic League; It is the native town of the duke Jacob; In 1595-1618, has been a capital of Kurland. Kuldiga is a province town of the Baltic region where number of unique values is concentrated at one place. There is specific town environment with unrepeatable social life where dominates throw centuries unchanged romantic and intimate spirit. Kuldiga old town fulfils following criteria – site of cultural and historical interest that have particular European significance for Member States in general and urban and natural area, riverside archaeological site. -

Couronians | Semigallians | Selonians

BALTS’ ROAD, THE COURONIAN ROUTE SEGMENT Route: Rucava – Liepāja – Grobiņa – Jūrkalne – Alsunga – Kuldīga – Ventspils – Talsi – Valdemārpils – Sabile – Saldus – Embūte – Mosėdis – Plateliai – Kretinga – Klaipėda – Palanga – Rucava Duration: 3–4 days. Length about 790 km In ancient times, Couronians lived on the coast of the Baltic Sea. At that time, the sea and rivers were an important waterway that inuenced their way of life and interaction with neighbouring nations. You will nd out about this by taking the circular Couronian Route Segment. Peaceful deals were made during trading. Merchants from faraway lands Macaitis, Tērvete Tourism Information Centre, Zemgale Planning Region. Planning Zemgale Centre, Information Tourism Tērvete Macaitis, were tempted to visit the shores of the Baltic Sea looking for the northern gold – Photos: Līva Dāvidsone, Artis Gustovskis, Arvydas Gurkšnis, Denisas Nikitenka, Mindaugas Mindaugas Nikitenka, Denisas Gurkšnis, Arvydas Gustovskis, Artis Dāvidsone, Līva Photos: Publisher: Kurzeme Planning Region, Zemgale Planning Region 2019 Region Planning Zemgale Region, Planning Kurzeme Publisher: amber. To nd out more about amber, visit the Palanga Amber Museum (40) Centre, National Regional Development Agency in Lithuania. in Agency Development Regional National Centre, and the Liepāja Crafts House (6). Ancient Couronian boats, the barges, are Authors: Kurzeme Planning Region, Zemgale Planning Region, Šiauliai Tourism Information Information Tourism Šiauliai Region, Planning Zemgale Region, Planning Kurzeme Authors: -

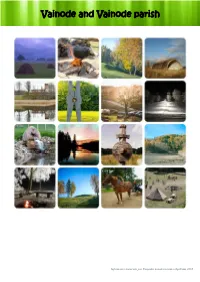

Vainode and Vainode Parish

Vainode and Vainode parish Informatīvs materiāls par Vaiņodes novada tūrisma objektiem 2016 At the end of the 12th century, the current area of Vainode Parish was situated on the south side of a Curonian land called Bandava. In 1253, Vainode became a part of the Bishopric of Courland, which then changed to the District of Piltene in 1585, and subsequently to the Courland Governorate of the Russian Empire in 1795. Development of Vainode began along with the construction of the Liepaja- Mazeikiai railway line in 1871. At the end of the 19th century, the land of Vainode Manor near Vainode Railway Station turned into a village which was mostly populated by the brickkiln and sawmill workers, while the nearby land of Lielbata Manor turned into a village of summer cottages. In 1912, construction work of one of the largest military airbases in the Baltic States was launched. During the independence period this was one of the cradles of aviation in Latvia. During World War I, German forces built two airship hangars next to the aerodrome which were dismantled and taken to Riga (now the home of Riga Central Market) in the 1920s, 16 hangars still remain at the aerodrome as well as 1800 m of a once 2500 m long runway. In the 1930s, Vainode was also known as a resort destination with very clean air. Vainode was the home of a sanatorium for state officials, mother and child care center as well as tuberculosis hospital. Vainode was occupied by the Red Army during World War II on 9 October 1944.