Slum Areas in Battambang and Climate Resilience 1. Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ggácmnmucrmhvisambaøkñú

01116406 F1/3.1 ŪĮйŬď₧şŪ˝˝ņįО ď ďijЊ ⅜₤Ĝ ŪĮйņΉ˝℮Ūij GgÁCMnMuCRmHvisamBaØkñúgtulakarkm <úCa Kingdom of Cambodia Nation Religion King Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia Royaume du Cambodge Chambres Extraordinaires au sein des Tribunaux Cambodgiens Nation Religion Roi Β₣ðĄеĕНеĄŪņйijНŵŁũ˝еĮРŲ Supreme Court Chamber Chambre de la Cour suprême TRANSCRIPT OF APPEAL PROCEEDINGS PUBLIC Case File Nº 002/19-09-2007-ECCC/SC 6 July 2015 Before the Judges: KONG Srim, Presiding The Accused: NUON Chea Ya Narin KHIEU Samphan Agnieszka KLONOWIECKA-MILART SOM Sereyvuth Chandra Nihal JAYASINGHE Lawyers for the Accused: MONG Monichariya Victor KOPPE Florence N. MWACHANDE-MUMBA LIV Sovanna SON Arun KONG Sam Onn Trial Chamber Greffiers/Legal Officers: Arthur VERCKEN Volker NERLICH SEA Mao Sheila PAYLAN Lawyers for the Civil Parties: Paolo LOBBA Marie GUIRAUD PHAN Thoeun HONG Kimsuon SIN Soworn TY Srinna For the Office of the Co-Prosecutors: VEN Pov Nicholas KOUMJIAN SONG Chorvoin For Court Management Section: UCH Arun 01116407 F1/3.1 Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia Supreme Court Chamber – Appeal Case No. 002/19-09-2007-ECCC/SC 06/07/2015 I N D E X Mr. TOIT Thoeurn (SCW-5) Questioning by The President KONG Srim ......................................................................................... page 2 Questioning by Mr. KOPPE .................................................................................................................. page 6 Questioning by Mr. VERCKEN .......................................................................................................... -

Slum Areas in Battambang and Climate Resilience

Asian Journal for Public Opinion Research - ISSN 2288-6168 (Online) 104 Vol. 5 No.2 February 2018: 104-126 http://dx.doi.org/10.15206/ajpor.2018.5.2.104 Slum Areas in Battambang and Climate Resilience Rem Samnang Hay Chanthol1 Faculty of Sociology and Community Development, University of Battambang, Cambodia Abstract As the second most populous province in Cambodia, Battambang also exhibits an increasing number of urban poor areas. This research focuses on the economic situation of slum areas in Battambang and how people in slum areas are affected by climate change. This research report describes socioeconomics of people living in slum areas in 4 villages in Battambang City. An investigation will be made on motivation of moving to slum areas, access to water, access to sanitation, access to electricity, transport and delivery, access to health care, access to education, security of tenure, cost of living in slum, literacy, and access to finance. We also explore the policy of the public sector toward climate change in Cambodia. Keywords: slum, climate change, climate resilience, poverty 1 All correspondence concerning to this paper should be addressed to Hay Chantol at the University of Battambang, National Road 5, Sangkat Preaek Preah Sdach, Battambang City, Battambang Province, Cambodia or by email at [email protected]. Asian Journal for Public Opinion Research - ISSN 2288-6168 (Online) 105 Vol. 5 No.2 February 2018: 104-126 http://dx.doi.org/10.15206/ajpor.2018.5.2.104 Introduction Battambang is a rice bowl of Cambodia. The total rice production in the province accounted for 8.5% of the total rice production of 9.3 million tons in 2013. -

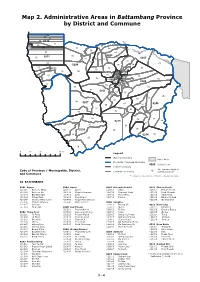

Map 2. Administrative Areas in Battambang Province by District and Commune

Map 2. Administrative Areas in Battambang Province by District and Commune 06 05 04 03 0210 01 02 07 04 03 04 06 03 01 02 06 05 0202 05 0211 01 0205 01 10 09 08 02 01 02 07 0204 05 04 05 03 03 0212 05 03 04 06 06 06 04 05 02 03 04 02 02 0901 03 04 08 01 07 0203 10 05 02 0208 08 09 01 06 10 08 06 01 04 07 0201 03 07 02 05 08 06 01 04 0207 01 0206 05 07 02 03 03 05 01 02 06 03 09 03 0213 04 02 07 04 01 05 0209 06 04 0214 02 02 01 0 10 20 40 km Legend National Boundary Water Area Provincial / Municipal Boundary 0000 District Code District Boundary The last two digits of 00 Code of Province / Municipality, District, Commune Boundary Commune Code* and Commune * Commune Code consists of District Code and two digits. 02 BATTAMBANG 0201 Banan 0204 Bavel 0207 Rotonak Mondol 0211 Phnom Proek 020101 Kantueu Muoy 020401 Bavel 020701 Sdau 021101 Phnom Proek 020102 Kantueu Pir 020402 Khnach Romeas 020702 Andaeuk Haeb 021102 Pech Chenda 020103 Bay Damram 020403 Lvea 020703 Phlov Meas 021103 Chak Krey 020104 Chheu Teal 020404 Prey Khpos 020704 Traeng 021104 Barang Thleak 020105 Chaeng Mean Chey 020405 Ampil Pram Daeum 021105 Ou Rumduol 020106 Phnum Sampov 020406 Kdol Ta Haen 0208 Sangkae 020107 Snoeng 020801 Anlong Vil 0212 Kamrieng 020108 Ta Kream 0205 Aek Phnum 020802 Norea 021201 Kamrieng 020501 Preaek Norint 020803 Ta Pun 021202 Boeung Reang 0202 Thma Koul 020502 Samraong Knong 020804 Roka 021203 Ou Da 020201 Ta Pung 020503 Preaek Khpob 020805 Kampong Preah 021204 Trang 020202 Ta Meun 020504 Preaek Luong 020806 Kampong Prieng 021205 Ta Saen 020203 -

Department of Potable Water Supply, Ministry of Industry, Mines and Energy Kingdom of Cambodia

DEPARTMENT OF POTABLE WATER SUPPLY, MINISTRY OF INDUSTRY, MINES AND ENERGY KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA PREPARATORY SURVEY ON THE PROJECT ON ADDITIONAL NEW WATER TREATMENT PLANTS FOR KAMPONG CHAM AND BATTAMBANG WATERWORKS IN THE KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA FINAL REPORT MARCH 2013 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) NIHON SUIDO CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. WATER AND SEWER BUREAU, CITY OF KITAKYUSHU CTI ENGINEERING INTERNATIONAL CO., LTD. Summary 1. Overview of the Kingdom of Cambodia (1) Natural Condition The total landmass of the Kingdom of Cambodia (hereinafter referred to as Cambodia) is approximately 181,000 km2 (a little less than the half of Japan’s total area). The Mekong River traverses the country from north to south, crossing the boundary with Lao PDR in the north. The Tonle Sap Lake and the river systems are the dominant features forming the Central Plains which cover three quarters of the country’s area. The Tonle Sap River runs off the Tonle Sap Lake and joins together with the Mekong River at the capital city of Phnom Penh. To the north and northeast, near the boundaries with Viet Nam and Lao PDR, are mountain ranges with dense virgin forests and diverse wildlife. According to the 2008 census, Cambodia has an estimated population of 1,340,000 people. Cambodia, lying entirely within the tropics, has a hot and humid climate, which is divided into wet (June to October) and dry (November to May) seasons. Severe heat occurs especially in the second half of the dry season (February to May) and the day time temperature can rise up to 30 to 40 ℃. -

MTF - Facility (FINAL)

This PDF generated by angkor, 11/13/2017 3:55:05 AM Sections: 4, Sub-sections: 7, Questionnaire created by angkor, 3/23/2017 7:59:26 AM Questions: 148. Last modified by angkor, 6/12/2017 8:57:40 AM Questions with enabling conditions: 74 Questions with validation conditions: 24 Not shared with anyone Rosters: 2 Variables: 0 WB - MTF - Facility (FINAL) A. INTERVIEW IDENTIFICATION No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 8. INFORMED CONSENT No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 2, Static texts: 1. B. FACILITY Sub-sections: 7, Rosters: 2, Questions: 127. C. CONTACT DETAILS No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 11. APPENDIX A — OPTIONS APPENDIX B — OPTION FILTERS LEGEND 1 / 22 A. INTERVIEW IDENTIFICATION SURVEY_ID TEXT SURVEYID SCOPE: IDENTIFYING A1 - Province SINGLE-SELECT A1 01 Banteay Meanchey 02 Battambang 03 Kampong Cham 04 Kampong Chhnang 05 Kampong Speu 06 Kampong Thom 07 Kampot 08 Kandal 09 Kep 10 Koh Kong 11 Kracheh 12 Mondul Kiri 13 Otdar Meanchey 14 Pailin 15 Phnom Penh 16 Preah Sihanouk And 9 other [1] A3 - District SINGLE-SELECT: CASCADING A3 001 Malai 002 Mongkol Borei 003 Ou Chrov 004 Paoy Paet 005 Phnum Srok 006 Serei Saophoan 007 Svay Chek 008 Thma Puok 009 Banan 010 Battambang 011 Bavel 012 Koas Krala 013 Moung Ruessei 014 Phnum Proek 015 Rotonak Mondol 016 Sampov Lun And 125 other [2] A5 - Commune SINGLE-SELECT: CASCADING A5 001 Ta Kong 002 Kouk Ballangk 003 Ruessei Kraok 004 Changha 005 Paoy Paet 006 Phsar Kandal 007 Ponley 008 Srah Chik 009 Ou Ambel 010 Preah Ponlea 011 Phkoam 012 Phum Thmei 013 Ta Kream 014 Chamkar Samraong 015 Kdol Doun Teav A. -

ERN>01580821</ERN>

ERN>01580821</ERN> D362 2 Annex ~ Civil Party Applications Declared Inadmissible ~ ~~~~ q { £ ¦ 1 ’ s 5 q £ I ê“ Full Name Reasons for Province Cambodian HIE 1 Indmissibility Finding Lawyer [Foreign Lawyer si 6~ ÏZ G 2 c —II W~ 2Æ 43 §£ ¦ The Applicant described the following Enslavement and OIA incl inhumane conditions of in Commune Phnom On living Applicant Spean Sreng 2 N Srok District Province from 1976 1978 ~ Banteay Meanchey imprisonment ~ 2 02 ~ Phnum Trayoung Prison Phnum Lieb Commune Preah Net Preah District C 3 PRAK Kav Banteay Meanchey 5 Chet Vanly r C 3 Banteay Meanchey Province in 1978 persecution of Vietnamese perceived 3 Applicant does not state she is Vietnamese but was targeted because she £2^ was accused of being Vietnamese Although it is recognised that this may be traumatising the facts described fall outside of the scope of the case file The Applicant described the following Enslavement and OIA incl inhumane living conditions of Applicant and family in Paoy Char Commune Phnom Srok District Banteay Meanchey Province throughout DK death of CN a N Applicant s sister at Trapeang Thma Dam in 1976 forced marriage of CO ~ „2 Applicant in Srah Chik Commune Phnom Srok District in 1976 death of 02 ~ S SO Sakhai 5 Applicant s father as result of untreated illness in Srah Chik Commune in Banteay Meanchey 5 Chet Vanly s ~ 3 a 2 late 1978 murder of Applicant s brother and cousin in Srah Chik 2 Commune in 1978 cousins and uncle murder of s uncle and Applicant » another cousin at unspecified location during DK Although it is recognised -

Cities and Provinces of Cambodia Юšijʼn-Ū˝О₣ Аĕ Ūįйŭď

CITIES AND PROVINCES OF CAMBODIA (English and Khmer Languages) ЮŠijʼn-Ū˝₣О аĕ ŪĮйŬď₧şŪ˝˝ņįОď (ļ⅜Β₣сЮÐų₤ ĕЊ₣ļ⅜ЯŠŊũ) English language: page 2 to 116 (unaltered transliteration) Khmer language: page 117 to 218 Source: http://www.cambodia.gov.kh Compiled by: Bunleng CHEUNG (UNAKRT-ECCC Translator) As of June 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Province Page BANTEAY MEANCHEY ........................................................................... 4 BATTAMBANG ......................................................................................... 9 KAMPONG CHAM .................................................................................. 15 KAMPONG CHHNANG........................................................................... 27 KAMPONG SPEU..................................................................................... 32 KAMPONG THOM................................................................................... 40 KAMPOT .................................................................................................. 45 KANDAL .................................................................................................. 50 KOH KONG .............................................................................................. 59 KRATIE .................................................................................................... 61 KRONG KEP............................................................................................. 64 KRONG PAILIN ...................................................................................... -

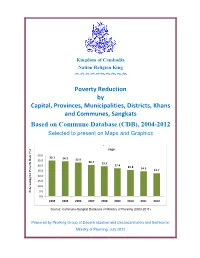

Capi Base Ital, Pr Ed on P Rovince and Comm Povert Es, Mu Comm Mune

Kingdom of Cambodia Nation Religion King rrrrrsssss Poverty Reduction by Capital, Provinces, Municipalities, Districts, Khans and Communes, Sangkats Based on Commune Database (CDB), 2004-2012 Selected to present on Maps and Graphics Nមationalធយមថន ក Av់ជeតrageិ 40.0 35.1 34.2 35.0 32.9 30.7 29.3 30.0 27.4 25.8 24.5 25.0 22.7 20.0 15.0 10.0 Forecasting for Poverty Rate (%) Rate (%) for Poverty Forecasting 5.0 0.0 2004 2005 2006 200720082009 2010 2011 2012 Source: Commune-Sangkat Database of Ministry of Planning (2003-2011) Prepared by Working Group of Decentralization and Deconcentration and Sethkomar Ministry of Planning, July 2012 Preface The Commune Database (CDB) has been established and purposed for responding the needs of Commune-Sangkat (C/S) in the process of C/S development planning and investment program as well as any decision making. The CDB collection is regularly conducted at the second-mid of December in every year. Working Group of Decentralization and Deconcentration and Sethkomar (WGDDS) of Ministry of Planning (MoP) who is led by H.E. Hou Taing Eng, Secretary of State, has studied and prepared the questionnaires for the data collection and transformed the raw data into the computer systems for Capital, Provinces (CP), Municipalities, Districts and Khans (MDK) and C/S of database. This WGDDS has also regularly spent it efforts to deliver the trainings to CP planning officers and relevant stakeholders to become the master of trainers, and to be capable for obligated officers in order to support the C/S councils. -

Map 4. Administrative Areas in Battambang Province by District and Commune

Map 4. Administrative Areas in Battambang Province by District and Commune 0210 07 04 06 03 02 06 05 0202 0211 01 0205 01 10 09 08 0204 02 01 07 05 04 05 03 03 06 05 03 04 06 06 0212 05 02 04 04 02 09 03 02 04 03 01 01 08 05 07 0203 10 08 02 0208 09 01 06 10 01 08 06 0201 04 07 03 07 02 05 06 04 08 01 0207 01 05 07 02 03 03 05 01 02 0206 06 03 09 03 04 0213 02 07 04 11 05 06 0209 04 12 02 01 0 10 20 40 km Legend National Boundary Water area Provincial / Municipal Boundary 0000 District Code District Boundary The last two digits of 00 Code of Province / Municipality, District, Commune Boundary Commune Code* and Commune * Commune Code consists of District Code and two digits. 02 BATTAMBANG 0201 Banan 0204 Bavel 0207 Rotanak Mondol 0211 Phnum Proek 020101 Kantueu Muoy 020401 Bavel 020701 Sdau 021101 Phnom Proek 020102 Kantueu Pir 020402 Khnach Romeas 020702 Andaeuk Haeb 021102 Pech Chenda 020103 Bay Damram 020403 Lvea 020703 Phlov Meas 021103 Chak Krey 020104 Chheu Teal 020404 Prey Khpos 020704 Traeng 021104 Barang Thleak 020105 Chaeng Mean Chey 020405 Ampil Pram Daeum 021105 Ou Rumduol 020106 Phnum Sampov 020406 Kdol Ta Haen 0208 Sangkae 020107 Snoeng 020801 Anlong Vil 0212 Kamrieng 020108 Ta Kream 0205 Aek Phnum 020802 Norea 021201 Kamrieng 020501 Preaek Norint 020803 Ta Pun 021202 Boeung Reang 0202 Thma Koul 020502 Samraong Knong 020804 Roka 021203 Ou Da 020201 Ta Pung 020503 Preaek Khpob 020805 Kampong Preah 021204 Trang 020202 Ta Meun 020504 Preaek Luong 020806 Kampong Prieng 021205 Ta Saen 020203 Ou Ta Ki 020505 Peam Aek 020807 Reang -

Battambang(PDF:327KB)

Index Map 2-2. Districts and Communes in Battambang Province Code of Province / Municipality, District, and Commune 0207 Rotonak Mondol 020701 Sdau 02 BATTAMBANG 06 020702 Andaeuk Haeb 05 04 020703 Phlov Meas 0201 Banan 03 0210 020704 Traeng 020101 Kantueu Muoy 01 02 07 020102 Kantueu Pir 0208 Sangkae 020103 Bay Damram 04 03 04 06 020801 Anlong Vil 03 020104 Chheu Teal 020802 Norea 01 02 020105 Chaeng Mean Chey 020803 Ta Pun 06 020106 Phnum Sampov 05 0202 020804 Roka 05 0211 01 020107 Snoeng 020805 Kampong Preah 01 10 08 0205 09 020108 Ta Kream 020806 Kampong Prieng 02 01 02 07 020807 Reang Kesei 0204 05 04 0202 Thma Koul 020808 Ou Dambang Muoy 020201 Ta Pung 05 0212 03 03 020809 Ou Dambang Pir 05 03 020202 Ta Meun 020810 Vaot Ta Moem 04 06 06 06 020203 Ou Ta Ki 02 04 05 020204 Chrey 03 04 02 0209 Samlout 02 0901 03 04 020205 Anlong Run 08 020901 Ta Taok 01 05 020206 Chrouy Sdau 07 0203 10 02 020902 Kampong Lpov 08 0208 020207 Boeng Pring 09 020903 Ou Samrel 01 020208 Kouk Khmum 06 10 020904 Sung 08 06 020209 Bansay Traeng 01 04 020905 Samlout 020210 Rung Chrey 07 0201 020906 Mean Chey 03 07 020907 Ta Sanh 02 0203 Krong Battambang 05 020301 Sangkat Tuol Ta Aek 06 0210 Sampov Lun 08 020302 Sangkat Preaek Preah Sdach 01 021001 Sampov Lun 04 020303 Sangkat Rotanak 021002 Angkor Ban 0207 01 0206 05 07 020304 Sangkat Chamkar Samraong 021003 Ta Sda 020305 Sangkat Sla Kaet 021004 Santepheap 02 03 020306 Sangkat Kdol Daun Teav 021005 Serei Mean Chey 05 03 01 020307 Sangkat Ou Mal 021006 Chrey Seima 02 020308 Sangkat Voat Kor 020309 Sangkat Ou -

Cambodia Post-Flood Relief and Recovery Survey 2012

Project Number: 46009Project Number: 26194 May 2012 Cambodia: Flood Damage Emergency Reconstruction Project Cambodia Post-Flood Relief and Recovery Survey 2012 CAMBODIA POST-FLOOD RELIEF 2012 AND RECOVERY SURVEY CAMBODIA POST-FLOOD RELIEF AND RECOVERY SURVEY May 2012 CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE TABLES AND FIGURES vi ABBREVIATIONS viii FOREWORD ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS x EXECUTIVE SUMMARY xi MAP OF SURVEYED VILLAGES xiv SECTION 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Survey Objectives 1 SECTION 2 METHODOLOGY 2 2.1 Survey Design 2 2.2 Sample Size 2 2.3 Sampling 3 First Stage 3 Second Stage 3 Missing Households and Children 3 Informed Consent and Refusals 3 2.4 Training and Pre-Testing 3 2.5 Fieldwork Logistics 4 2.6 Survey Questionnaires 4 2.7 Data Quality Control 4 2.8 Data Entry, Processing, Cleaning 5 2.9 Data Analysis 5 2.10 Sample Coverage 5 SECTION 3 HOUSEHOLD CHARACTERISTICS 6 3.1 Household Composition 6 3.2 Household Characteristics 6 Source of Drinking Water 6 Type of Toilet Facility 6 Hand Washing and Soap Availability 6 Housing Materials 6 Source of Cooking Fuel 8 IDPoor Status 8 3.3 Household Possessions 8 Asset Ownership 8 3.4 Household Wealth 8 3.5 Education of Mothers 8 3.6 School Attendance of Children 5-14 Years 10 3.7 Background Characteristics of Children 0-59 Months 10 CAMBODIA iii Post-Flood Relief and Recovery Survey 2012 CONTENTS SECTION 4 GENERAL EFFECTS 11 4.1 Information and Communication 11 Types of Information 11 Sources of Information 11 Preferred Source of Information 12 4.2 Household Displacement 12 4.3 Infrastructure -

Microsoft Office 2000

Electricity Authority of Cambodia ELECTRICITY AUTHORITY OF CAMBODIA REPORT ON POWER SECTOR OF THE KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA 2009 EDITION Compiled by EAC from the informations received till end of 2008 November, 2009 Report on Power Sector for the Year 2007 0 Electricity Authority of Cambodia Preface The Annual Report on Power Sector of the Kingdom of Cambodia, 2009 Edition is compiled from informations received from the licensees, MIME and other organizations in the power sector till the end of 2008. This report is for dissemination to the Royal Government, institutions, investors and public desirous to know about the present situation of the power sector of the Kingdom of Cambodia. This report is compiled from information collected by EAC and information taken from licensees’ annual summary report on their activities during the Year 2008. Till the end of year 2008, 218 licensed electricity service providers share about 98% of power market in the kingdom of Cambodia. Among them EDC, the distribution licensees, the licensees supplying electricity in provincial towns and other big towns manage the service well, and keep their operational records to the required level of quality. Most of the small licensees supplying electricity in rural areas, cannot manage their operation at the required level, causing many inaccuracies in their data record. However as the power market share of this group of licensees is small (less than 2%); this will not materially affect the overall accuracy of the data furnished in this report. However, EAC gives special attention to the collection of the data done by it from these licensees and trains them to record the required data correctly as the data is important in assessing the real situation of rural electrification.