Miss Saigon: the Asian Experience in the Perspective of the White Man

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colonial Concert Series Featuring Broadway Favorites

Amy Moorby Press Manager (413) 448-8084 x15 [email protected] Becky Brighenti Director of Marketing & Public Relations (413) 448-8084 x11 [email protected] For Immediate Release, Please: Berkshire Theatre Group Presents Colonial Concert Series: Featuring Broadway Favorites Kelli O’Hara In-Person in the Berkshires Tony Award-Winner for The King and I Norm Lewis: In Concert Tony Award Nominee for The Gershwins’ Porgy & Bess Carolee Carmello: My Outside Voice Three-Time Tony Award Nominee for Scandalous, Lestat, Parade Krysta Rodriguez: In Concert Broadway Actor and Star of Netflix’s Halston Stephanie J. Block: Returning Home Tony Award-Winner for The Cher Show Kate Baldwin & Graham Rowat: Dressed Up Again Two-Time Tony Award Nominee for Finian’s Rainbow, Hello, Dolly! & Broadway and Television Actor An Evening With Rachel Bay Jones Tony, Grammy and Emmy Award-Winner for Dear Evan Hansen Click Here To Download Press Photos Pittsfield, MA - The Colonial Concert Series: Featuring Broadway Favorites will captivate audiences throughout the summer with evenings of unforgettable performances by a blockbuster lineup of Broadway talent. Concerts by Tony Award-winner Kelli O’Hara; Tony Award nominee Norm Lewis; three-time Tony Award nominee Carolee Carmello; stage and screen actor Krysta Rodriguez; Tony Award-winner Stephanie J. Block; two-time Tony Award nominee Kate Baldwin and Broadway and television actor Graham Rowat; and Tony Award-winner Rachel Bay Jones will be presented under The Big Tent outside at The Colonial Theatre in Pittsfield, MA. Kate Maguire says, “These intimate evenings of song will be enchanting under the Big Tent at the Colonial in Pittsfield. -

Curran San Francisco Announces Cast for the Bay Area Premiere of Soft Power a Play with a Musical by David Henry Hwang and Jeanine Tesori

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Curran Press Contact: Julie Richter, Charles Zukow Associates [email protected] | 415.296.0677 CURRAN SAN FRANCISCO ANNOUNCES CAST FOR THE BAY AREA PREMIERE OF SOFT POWER A PLAY WITH A MUSICAL BY DAVID HENRY HWANG AND JEANINE TESORI JUNE 20 – JULY 10, 2018 SAN FRANCISCO (March 6, 2018) – Today, Curran announced the cast of SOFT POWER, a play with a musical by David Henry Hwang (play and lyrics) and Jeanine Tesori (music and additional lyrics). SOFT POWER will make its Bay Area premiere at San Francisco’s Curran theater (445 Geary Street), June 20 – July 8, 2018. Produced by Center Theatre Group, SOFT POWER comes to Curran after its world premiere at the Ahmanson Theatre in Los Angeles from May 3 through June 10, 2018. Tickets for SOFT POWER are currently only available to #CURRAN2018 subscribers. Single tickets will be announced at a later date. With SOFT POWER, a contemporary comedy explodes into a musical fantasia in the first collaboration between two of America’s great theatre artists: Tony Award winners David Henry Hwang (M. Butterfly, Flower Drum Song) and Jeanine Tesori (Fun Home). Directed by Leigh Silverman (Violet) and choreographed by Sam Pinkleton (Natasha, Pierre, & the Great Comet of 1812), SOFT POWER rewinds our recent political history and plays it back, a century later, through the Chinese lens of a future, beloved East-meets-West musical. In the musical, a Chinese executive who is visiting America finds himself falling in love with a good-hearted U.S. leader as the power balance between their two countries shifts following the 2016 election. -

How to Host a Geography Quiz Night

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC EDUCATION Geography Awareness Week How to Host a Geography Quiz Night Quiz or Trivia nights have been a pastime for people all over the world and been used as a fun fundraising tool for many groups. These can be at home, in a bar or restaurant, at a student union, lounge, church hall… really anywhere! Celebrating Geography Awareness Week can be really fun, but also stressful if you are unsure how to start. Use this guide to plan a quiz night to spread awareness where you are. 1. Establish a planning team: Seek support for the event from your principal/ adviser/ other key leaders. Form a team with volunteers or other interested organizations. Clearly define and divide roles and responsibilities among a few team members, and meet regularly for event planning. Consider the following team member roles: • Event Leader: Oversees events activities and timeline; organizes communication among team members; coordinates volunteers to help before, during and after the event. Will be the venue liaison and may need to be the mediator should play get out of hand. • Host: Should be well-spoken, personable, enjoys public speaking, can get a crowd excited and having a good time but will also be organized and able to ensure that everyone is being fair and friendly. • Promotions Coordinator: Places Geography Awareness Week posters in and around schools and throughout communities; coordinates invitations; connects with event partners and sponsors; contacts local and national TV, radio stations, and newspapers. 2. Plan your event: Allow about two months or more to plan the event. Consult with school administrators or other appropriate officials when selecting a time and place for your event. -

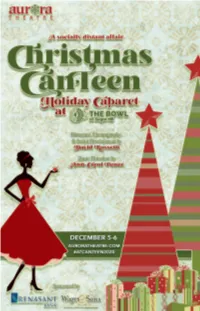

Canteen2020program.Pdf

PRODUCTION STAFF Assistant Stage Manager .................................................................................. RENITA JAMES Assistant Technical Director .......................................................................... ASHLEY HOGAN E Scenic Painter ............................................................................................... SARAH THOMSON H T Spotlight Operator ................................................. FIO MU N DLA TAI OYN MOLLY HUNTINGTON & JON SANDMAIER BAND Music Director........................................................................................... ANN-CAROL PENCE Perussion ............................................................................................................MARK BIERING Bass .................................................................................................................. DON KLAYMAN Aurora Theatre, Inc. is a 501(c)(3) non-profit corporation and receives support through grants and/or membership Guitar ................................................................................................................... opportunities from the above organizations. BRIAN SMITH 2 AURORA THEATRE Order Tickets Online auroratheatre.com • 678.226.6222 3 FROM THE PRODUCERS CAST BIOGRAPHIES is thrilled to be back at the Aurora Theatre. He - MICHAEL CRUTE “Keep some room in your heart for the unimaginable.” Mary Oliver recently had his Aurora Theatre debut in Aurora’s summer production This has been a year of waiting. This pandemic has sent our county, -

Miss Saigon Playbill.Pdf

JULY 8 - JULY 25 We are celebrating our 60th Anniversary this season. Gateway Playhouse Bellport, brings you the show you are about to see, which is the third in our six show Broadway Series. Inside you will find an article depicting the third decade in our long history of bringing professional theater to Long Island. Gateway Playhouse 1 WmJONeill FP 08 5/14/08 1:14 PM Page 1 Established In 1910. Famous for almost 100 Years. Visit the Pine Grove Inn and Experience its Old World Charm Sales Exchange Co., Inc. Jewelers and Collateral Loanbrokers Pine Grove Inn • Open for Lunch and Dinner overlooks the lovely Swan River in Patchogue Tuesday through Sunday • Join us every Friday from 4-6pm for Happy Hour & Complimentary Buffet Classic and • Live Music Friday & Saturday Evenings Contemporary Now Serving Sunday Brunch 11am-2pm • Extensive menu is filled with something for everyone New Prix Fixe Menu $24.95 Lunch & Dinner • Fresh Local Seafood • Prime Steaks Soup or Salad • Entrée • Dessert • Coffee • Tea • Traditional German Classics Available Sunday through Thursday • Catering for all occasions – Not available on holidays or for parties greater than fifteen. (3 separate rooms) Platinum Tuesday & Wednesday and Gold Lobsterfest Thursday Prime Rib Night Jewelry designs that will 1 First Street, East Patchogue • 631-475-9843 excite your senses. Check our website: www.pinegroveinn.com for the current entertainment schedule. S. C ou ntr Closed Mondays y Rd. First St. Expert Jewelry Repairs PRESENT THIS VOUCHER FOR PRESENT THIS VOUCHER FOR One East Main St., Patchogue 631.289.9899 www.wmjoneills.com $5 OFF LUNCH $10 OFF DINNER on checks of $35 or more on checks of $80 or more 2 Mention this ad for 10% discount on purchase Expires August 1, 2009. -

The Miss Saigon Controversy

The Miss Saigon Controversy In 1990, theatre producer Cameron Mackintosh brought the musical Miss Saigon to Broadway following a highly successful run in London. Based on the opera Madame Butterfly, Miss Saigon takes place during the Vietnam War and focuses on a romance between an American soldier and a Vietnamese orphan named Kim. In the musical, Kim is forced to work at ‘Dreamland,’ a seedy bar owned by the half-French, half-Vietnamese character ‘the Engineer.’ The production was highly anticipated, generating millions of dollars in ticket sales before it had even opened. Controversy erupted, however, when producers revealed that Jonathan Pryce, a white British actor, would reprise his role as the Eurasian ‘Engineer.’ Asian American actor B.D. Wong argued that by casting a white actor in a role written for an Asian actor, the production supported the practice of “yellow-face.” Similar to “blackface” minstrel shows of the 19th and 20th centuries, “yellow-face” productions cast non-Asians in roles written for Asians, often relying on physical and cultural stereotypes to make broad comments about identity. Wong asked his union, Actors’ Equity Association, to “force Cameron Mackintosh and future producers to cast their productions with racial authenticity.” Actors’ Equity Association initially agreed and refused to let Pryce perform: “Equity believes the casting of Mr. Pryce as a Eurasian to be especially insensitive and an affront to the Asian community.” Moreover, many argued that the casting of Pryce further limited already scarce professional opportunities for Asian American actors. Frank Rich of The New York Times disagreed, sharply criticizing the union for prioritizing politics over talent: “A producer's job is to present the best show he can, and Mr. -

Hollywood Pantages Theatre Los Angeles, California

® ® HOLLYWOODTHEATRE PANTAGES NAME THEATRE LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 03-277.16-8.11 Charlie Miss Cover.indd Saigon Pantages.indd 1 1 7/2/193/6/19 10:05 3:15 PMAM HOLLYWOOD PANTAGES THEATRE CAMERON MACKINTOSH PRESENTS BOUBLIL & SCHÖNBERG’S Starring RED CONCEPCIÓN EMILY BAUTISTA ANTHONY FESTA and STACIE BONO J.DAUGHTRY JINWOO JUNG at certain performances EYMARD CABLING plays the role The Engineer and MYRA MOLLOY plays the role of Kim. Music by CLAUDE-MICHEL SCHÖNBERG Lyrics by RICHARD MALTBY, JR. & ALAIN BOUBLIL Adapted from the Original French text by ALAIN BOUBLIL Additional lyrics by MICHAEL MAHLER Orchestrations by WILLIAM DAVID BROHN Musical Supervision by STEPHEN BROOKER Lighting Designed by BRUNO POET Projections by LUKE HALLS Sound Designed by MICK POTTER Costumes Designed by ANDREANE NEOFITOU Design Concept by ADRIAN VAUX Production Designed by TOTIE DRIVER & MATT KINLEY Additional Choreography by GEOFFREY GARRATT Musical Staging and Choreography by BOB AVIAN Directed by LAURENCE CONNOR For MISS SAIGON National Tour Casting by General Management TARA RUBIN CASTING GREGORY VANDER PLOEG MERRI SUGARMAN, CSA & CLAIRE BURKE, CSA for Gentry & Associates Executive Producers Executive Producer NICHOLAS ALLOTT & SETH SKLAR-HEYN SETH WENIG for Cameron Mackintosh Inc. for NETworks Presentations Associate Sound Designer Associate Costume Designer Associate Lighting Designers Associate Set Designer ADAM FISHER DARYL A. STONE WARREN LETTON & JOHN VIESTA CHRISTINE PETERS Resident Director Music Director Musical Supervisor Associate Choreographer Associate Director RYAN EMMONS WILL CURRY JAMES MOORE JESSE ROBB SETH SKLAR-HEYN A CAMERON MACKINTOSH and NETWORKS Presentation 4 PLAYBILL 7.16-8.11 Miss Saigon Pantages.indd 2 7/2/19 10:05 AM CAST (in order of appearance) ACT I SAIGON—1975 The Engineer ...................................................................................................RED CONCEPCIÓN Kim .................................................................................................................. -

My Fair Lady September 9-25, 2016 S M T W T F S Sept

AMERICA’S OLDEST CONTINUOUSLY OPERATING COMMUNITY THEATRE AUGUST 2016 Town Theatre’s 98th Season Presented by ~ Meet Henry Higgins, a brilliant, crotchety, middle-aged bachelor who is England’s leading phoneticist. Higgins, on his endless quest for new dialects of London’s speech, encounters Eliza Doolittle, a cockney gutter sparrow who makes her living selling violets. Eliza comes to Higgins in order to transform herself into a “lidy.” And thus the duel begins. This classic story is being brought back to the Town stage on its ten year anniversary of last being presented. Kerri Roberts (Mary Poppins, Beauty and the Beast) is our “fair lady” who goes nose to nose with Jeremy Hansard (Mary Poppins, The Little Mermaid) in the role of Henry Higgins. Town audiences will delight to see Bill DeWitt (Nice Work if You Can Get It, Dearly Departed) as Col. Pickering, Will Moreau (Miss Saigon, Annie Get Your Gun) as Eliza’s bumbling father, Alfred Doolittle, and Jeremy Reasoner (Les Misérables, Singin’ in the Rain) September 9–25, who brings his powerful tenor voice to the role of aristocrat Freddie, an unlikely suitor. 2016 Book and Lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner Director ~ Allison McNeely Music by Frederick Loewe Musical Director ~ Gloria Wright Choreographer ~ Joy Alexander Adapted from George Costumer ~ Janet Kile Scenic & Lighting Director ~ Danny Harrington Bernard Shaw’s Play and Gabriel Pascal’s Motion SPONSORED BY Picture “PYGMALION” Original Production Directed by Moss Hart My Fair Lady September 9-25, 2016 S M T W T F S Sept. 9 10 (8 pm) (8 pm) 11 15 16 17 (3 pm) (8 pm) (8 pm) (8 pm) 18 22 23 24 (3 pm) (8 pm) (8 pm) (8 pm) 25 (3 pm) Thursday,Friday and Saturday shows are at 8 PM. -

The New National Tour of Cameron Mackintosh's

Tweet it! Experience the acclaimed new production of @MissSaigonUS when it makes its premiere in Philly @KimmelCenter 03/19-03/31. More info at kimmelcenter.org. #BWYPHL #ArtHappensHere Press Contacts: Lauren Woodard Carole Morganti, CJM Public Relations (215) 790-5835 (609) 953-0570 [email protected] [email protected] THE NEW NATIONAL TOUR OF CAMERON MACKINTOSH’S DYNAMITE BROADWAY REVIVAL OF BOUBLIL AND SCHÖNBERG’S LEGENDARY MUSICAL MISS SAIGON ARRIVES IN PHILADELPHIA FOR ITS KIMMEL CENTER CULTURAL CAMPUS PREMIERE MARCH 19 – 31, 2019 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE (Philadelphia, PA, January 31, 2019) – Cameron Mackintosh’s acclaimed new production of Boublil and Schönberg’s legendary musical Miss Saigon —a smash hit in London, Broadway, and across the UK— comes to Philadelphia March 19 – 31, playing at the Academy of Music on the Kimmel Center Cultural Campus for the first time ever. “We are ecstatic to welcome this brand-new production of Miss Saigon to Philadelphia!” said Anne Ewers, President and CEO of the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts. “Our Broadway Philadelphia audiences will be spellbound by this epic love story along with the iconic Broadway score brought back to the stage in spectacular fashion as only Cameron Mackintosh can do.” Cameron Mackintosh said “It’s hard to believe that it has been over 27 years since Miss Saigon first opened in North America but, if anything, the tragic love story at the heart of the show has become even more relevant today with innocent people being torn apart by war all over the world. This brilliant new production, directed by Laurence Connor and featuring the original dazzling choreography by Bob Avian, takes a grittier, more realistic approach that magnifies the power and epic sweep of Boublil and Schönberg’s tremendous score. -

A Chorus Line Playbill.Indd

Diamond Head Theatre July 16 – Aug 8, 2021 Vol 106. No. 7 Diamond Head Theatre Presents Conceived and Originally Directed and Choreographed by MICHAEL BENNETT Book by JAMES KIRKWOOD and NICHOLAS DANTE Music by MARVIN HAMLISCH Lyrics by EDWARD KLEBAN Co Choregraphed by BOB AVIAN Musical Direction by Directed & Choreographed by Set & Lighting Design by MELINA LILLIOS GREG ZANE DAWN OSHIMA Costume Design by Props Design by Sound Design by KAREN G. WOLFE JOHN CUMMINGS III JUSTIN CHUN Co-Production Stage Managers CELIA CHUN & TOM BINGHAM Executive Director Artistic Director DEENA DRAY JOHN RAMPAGE Platinum Sponsors: CRUM & FORSTER FIRST HAWAIIAN BANK JOHN YOUNG FOUNDATION TOYOTA HAWAII Gold Sponsors: AMERICAN SAVINGS BANK C.S. WO & SONS CADES SCHUTTE CITY MILL HAWAII PACIFIC HEALTH FRANCES HISASHIMA MARIKO & JOE LYONS DAVID & NOREEN MULLIKEN CAROLYN BERRY WILSON WAKABAYASHI & BINGHAM FAMILIES A CHORUS LINE is presented by arrangement with Concord eatricals on behalf of Tams-Witmark LLC. concordtheatricals.com Finale Costumes Provided by COSTUME WORLD THEATRICAL, Deerfi eld Beach, FL. www.costumeworld.com Diamond Head Th eatre • 520 Makapuu Avenue, Honolulu, HI 96816 Phone (808) 733-0277 • Box Offi ce (808) 733-0274 • www.diamondheadtheatre.com Photographing, videotaping, or other video or audio recording of this production is strictly prohibited. Please turn o all cellular phones. Diamond Head Theatre Cast List Presents Zach Norm Dabalos Larry Levi K. Oliveira Don Chase Bridgman Maggie Marisa Noelle Mike Luke Ellis Connie Kayla Uchida Greg Gabriel Ryan-Kern Cassie Kira Mahealani Stone Sheila Lauren Teruya Bobby Marcus Stanger Bebe Miya Heulitt Judy Seanalei Nishimura Richie David Robinson Al Jared Paakaula Kristine Alexandria Zinov Val Jody Bill Mark Michael Hicks Paul Dwayne Sakaguchi Diana Emily North Lois Ke‘ala O'Connell Vicki Korynn Grenert Tricia Ayzhia Tadeo Frank Brandon Yim Roy Jackson Saunders A CHORUS LINE is performed without an intermission. -

LES MISÉRABLES National Tour

THE MUSICAL PHENOMENON DECEMBER 4–9, 2018 2018/2019 SEASON Great Artists. Great Audiences. Hancher Performances. CAMERON MACKINTOSH PRESENTS BOUBLIL & SCHÖNBERG’S A musical based on the novel by VICTOR HUGO Music by CLAUDE-MICHEL SCHÖNBERG Lyrics by HERBERT KRETZMER Original French text by ALAIN BOUBLIL and JEAN-MARC NATEL Additional material by JAMES FENTON Adaptation by TREVOR NUNN and JOHN CAIRD Original Orchestrations by JOHN CAMERON New Orchestrations by CHRISTOPHER JAHNKE STEPHEN METCALFE and STEPHEN BROOKER Musical Staging by MICHAEL ASHCROFT and GEOFFREY GARRATT Projections realized by FIFTY-NINE PRODUCTIONS Sound by MICK POTTER Lighting by PAULE CONSTABLE Costume Design by ANDREANE NEOFITOU and CHRISTINE ROWLAND Set and Image Design by MATT KINLEY inspired by the paintings of VICTOR HUGO Directed by LAURENCE CONNOR and JAMES POWELL For LES MISÉRABLES National Tour Casting by General Management TARA RUBIN CASTING/ GREGORY VANDER PLOEG KAITLIN SHAW, CSA for Gentry & Associates Executive Producers Executive Producers NICHOLAS ALLOTT & SETH SKLAR-HEYN SETH WENIG & TRINITY WHEELER for Cameron Mackintosh Inc. for NETworks Presentations Associate Sound Associate Costume Associate Lighting Associate Set Designer Designer Designer Designers NIC GRAY LAURA HUNT RICHARD PACHOLSKI DAVID HARRIS & CHRISTINE PETERS Resident Director Musical Director Musical Supervision Associate Director LIAM McILWAIN BRIAN EADS STEPHEN BROOKER & JAMES MOORE COREY AGNEW A CAMERON MACKINTOSH and NETWORKS Presentation 3 Photo: Matthew Murphy Matthew Photo: EVENT -

Racial Representation and Miss Saigon: a Zero Sum Game?

Tapestries: Interwoven voices of local and global identities Volume 8 Issue 1 Resisting Borders: Rethinking the Limits Article 6 of American Studies 2019 Racial Representation and Miss Saigon: A Zero Sum Game? Isabel P. S. Ryde Macalester College, [email protected] Keywords: musical theater, Miss Saigon, Broadway, Minnesota theater, race, Asian-American protest, Asian representation in media Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/tapestries Recommended Citation Ryde, Isabel P. S. (2019) "Racial Representation and Miss Saigon: A Zero Sum Game?," Tapestries: Interwoven voices of local and global identities: Vol. 8 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/tapestries/vol8/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the American Studies Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tapestries: Interwoven voices of local and global identities by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Racial Representation and Miss Saigon: A Zero Sum Game? Isabel (Izzy) P. S. Ryde Abstract People have been protesting and supporting the musical Miss Saigon since its premiere in 1989. The musical tale of a white American GI falling in love with a Vietnamese bargirl during the Vietnam War is praised for its diverse cast and showing the Vietnamese side of the war. Miss Saigon is also criticized for its stereotypical depiction of Asian women as prostitutes and Asian men as cold and treacherous. Both sides are passionate, and there is no clear consensus or majority opinion. What, then, is the value of Miss Saigon? Should it be banned or still performed? I analyze the different positions of the protesters, and compare their opinions to Miss Saigon supporters.