Migrant Workers in Ontario Tobacco ⇑ E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quaternary Geology of the Tillsonburg Area, Southern Ontario; Ontario Geological Survey, Report 220, 87P

ISSN 0704-2582 ISBN 0-7743-6983-3 THESE TERMS GOVERN YOUR USE OF THIS DOCUMENT Your use of this Ontario Geological Survey document (the "Content") is governed by the terms set out on this page ("Terms of Use"). By downloading this Content, you (the "User") have accepted, and have agreed to be bound by, the Terms of Use. Content: This Content is offered by the Province of Ontario's Ministry of Northern Development and Mines (MNDM) as a public service, on an "as-is" basis. Recommendations and statements of opinion expressed in the Content are those of the author or authors and are not to be construed as statement of government policy. You are solely responsible for your use of the Content. You should not rely on the Content for legal advice nor as authoritative in your particular circumstances. Users should verify the accuracy and applicability of any Content before acting on it. MNDM does not guarantee, or make any warranty express or implied, that the Content is current, accurate, complete or reliable. MNDM is not responsible for any damage however caused, which results, directly or indirectly, from your use of the Content. MNDM assumes no legal liability or responsibility for the Content whatsoever. Links to Other Web Sites: This Content may contain links, to Web sites that are not operated by MNDM. Linked Web sites may not be available in French. MNDM neither endorses nor assumes any responsibility for the safety, accuracy or availability of linked Web sites or the information contained on them. The linked Web sites, their operation and content are the responsibility of the person or entity for which they were created or maintained (the "Owner"). -

Annual Report 2019

Newcomer Tour of Norfolk County Student Start Up Program participants Tourism & Economic Development Annual Report 2019 Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ 3 Business Incentives & Supports ...................................................................................... 5 Investment Attraction ..................................................................................................... 11 Collaborative Projects ................................................................................................... 14 Marketing & Promotion .................................................................................................. 20 Strategy, Measurement & Success ............................................................................... 31 Performance Measurement ........................................................................................... 32 Advisory Boards ............................................................................................................ 33 Appendix ....................................................................................................................... 35 Staff Team ..................................................................................................................... 40 Prepared by: Norfolk County Tourism & Economic Development Department 185 Robinson Street, Suite 200 Simcoe ON N3Y 5L6 Phone: 519-426-9497 Email: [email protected] www.norfolkbusiness.ca -

Norfolk Rotary Clubs with 90+ Years of Community Service!

ROTARY AROUND THE WORLD IS OVER 100 YEARS OLD IN NORFOLK COUNTY ROTARY HAS SERVED THE COMMUNITY ROTARY CLUB OF FOR SIMCOE ROTARY CLUB OF OVER DELHI ROTARY CLUB NORFOLK SUNRISE YEARS90! NORFOLK ROTARACT CLUB 2 A Celebration of Rotary in Norfolk, June 2018 Welcome to the world of Rotary Rotary in Norfolk County Rotary International is a worldwide network of service clubs celebrating in Norfolk more than 100 years of global community service with a convention in Toronto at the end of June. Among the thousands of attendees will be PUBLISHED BY representatives from Norfolk County’s three clubs, as well as an affiliated Rotary Club of Simcoe, Rotary Club of Delhi, Rotary Club of Norfolk Sunrise and Rotaract Club in Norfolk Rotaract Club. ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER Rotary has had a presence in Norfolk County for more than 90 years. Media Pro Publishing Over that time, countless thousands of dollars have been donated to both David Douglas PO Box 367, Waterford, ON N0E 1Y0 community and worldwide humanitarian projects. 519-429-0847 • email: [email protected] The motto of Rotary is “Service Above Self” and local Rotarians have Published June 2018 amply fulfilled that mandate. Copywright Rotary Clubs of Norfolk County, Ontario, Canada This special publication is designed to remind the community of Rotary’s local history and its contributions from its beginning in 1925 to the present. Rotary has left its mark locally with ongoing support of projects and services such as Norfolk General Hospital, the Delhi Community Medical Centre and the Rotary Trail. Equally important are youth services and programs highlighted by international travel opportunities. -

Summer 2015 • Published at Vittoria, Ontario (519) 426-0234

SOME OF THE STUFF INSIDE 2015 Spaghetti Dinner & Auction 15 Flyboarding at Turkey Point 31 Smugglers Run 31 2015 OVSA Recipients 27 Happy 75th Anniversary 12 Snapd at the Auction 34 2015 Volunteers & Contributors 2 In Loving Memory of Ada Stenclik 30 Snapping Turtles 28 3-peat Canadian Champions 5 James Kudelka, Director 10 South Coast Marathon 30 Agricultural Hall of Fame 4 Lynn Valley Metal Artist 9 South Coast Shuttle Service 20 Alzheimer’s in Norfolk 14 Memories 3,32 St. Michael’s Natural Playground 21 Art Studio in Port Ryerse 15 MNR Logic 6 Tommy Land & Logan Land 11 Artist Showcase 14 North Shore Challenge 29 Vic Finds a Gem 14 Calendar of Events 36 Port Dover Pirates Double Champs 17 Vittoria Area Businesses 22 Carrie in OCAA Hall of Fame 8 Qigong in Port Ryerse 19 Walsh Volleyball Champs 13 Down Memory Lane 7 Radical Road Zipline 20 Zack Crandall First in Great Race 17 NO. 37 – SUMMER 2015 • PUBLISHED AT VITTORIA, ONTARIO (519) 426-0234 The Vittoria Booster The Vittoria Booster Newsletter is published twice a year by The Vittoria & District Foundation for its Members and Contributors. Booster e-mail: [email protected] website: http://www.vittoria.on.ca Foundation e-mail: [email protected] A n in front of a person’s name indicates that he or she is a member of The Vittoria & District Foundation Milestone Birthdays Celebrated nnWillie Moore, 75 on January 7 In Memoriam nnAda Stenclik, 100 on January 10 nnRoss Broughton, 85 on January 25 Howard John (Jack) King, æ 60, on January 18 nnEvelyn Oakes, 85 on January 31 R. -

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2009-39

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2009-39 Route reference: Broadcasting Public Notice 2008-21 Additional reference: Broadcasting Public Notice 2008-21-1 Ottawa, 2 February 2009 Various applicants London, Ontario Public Hearing in Cambridge, Ontario 20 October 2008 Licensing of new radio stations to serve London, Ontario The Commission approves the application by Blackburn Radio Inc. for a broadcasting licence to operate a new FM radio station to serve London. The licence will expire 31 August 2015. The Commission also approves the application by Sound of Faith Broadcasting, subject to certain conditions, for a broadcasting licence to operate a new FM radio station to serve London. The licence will expire 31 August 2012. The Commission denies the remaining applications for broadcasting licences for radio stations to serve London. A dissenting opinion by Commissioners Elizabeth Duncan and Peter Menzies is attached. Introduction 1. At a public hearing commencing 20 October 2008 in Cambridge, Ontario, the Commission considered nine applications for new radio programming undertakings to serve London, Ontario, some of which are mutually exclusive on a technical basis. The applicants were as follows: • Blackburn Radio Inc. • CTV Limited • Evanov Communications Inc., on behalf of a corporation to be incorporated • Forest City Radio Inc. • Frank Torres, on behalf of a corporation to be incorporated • My Broadcasting Corporation1 • Rogers Broadcasting Limited • Sound of Faith Broadcasting2 • United Christian Broadcasters Canada 2. As part of this process, the Commission received and considered interventions with respect to each application. The public record for this proceeding is available on the Commission’s website at www.crtc.gc.ca under “Public Proceedings.” 3. -

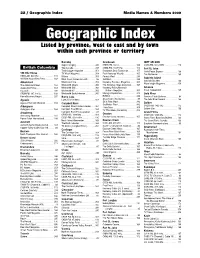

Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by Province, West to East and by Town Within Each Province Or Territory

22 / Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by province, west to east and by town within each province or territory Burnaby Cranbrook fORT nELSON Super Camping . 345 CHDR-FM, 102.9 . 109 CKRX-FM, 102.3 MHz. 113 British Columbia Tow Canada. 349 CHBZ-FM, 104.7mHz. 112 Fort St. John Truck Logger magazine . 351 Cranbrook Daily Townsman. 155 North Peace Express . 168 100 Mile House TV Week Magazine . 354 East Kootenay Weekly . 165 The Northerner . 169 CKBX-AM, 840 kHz . 111 Waters . 358 Forests West. 289 Gabriola Island 100 Mile House Free Press . 169 West Coast Cablevision Ltd.. 86 GolfWest . 293 Gabriola Sounder . 166 WestCoast Line . 359 Kootenay Business Magazine . 305 Abbotsford WaveLength Magazine . 359 The Abbotsford News. 164 Westworld Alberta . 360 The Kootenay News Advertiser. 167 Abbotsford Times . 164 Westworld (BC) . 360 Kootenay Rocky Mountain Gibsons Cascade . 235 Westworld BC . 360 Visitor’s Magazine . 305 Coast Independent . 165 CFSR-FM, 107.1 mHz . 108 Westworld Saskatchewan. 360 Mining & Exploration . 313 Gold River Home Business Report . 297 Burns Lake RVWest . 338 Conuma Cable Systems . 84 Agassiz Lakes District News. 167 Shaw Cable (Cranbrook) . 85 The Gold River Record . 166 Agassiz/Harrison Observer . 164 Ski & Ride West . 342 Golden Campbell River SnoRiders West . 342 Aldergrove Campbell River Courier-Islander . 164 CKGR-AM, 1400 kHz . 112 Transitions . 350 Golden Star . 166 Aldergrove Star. 164 Campbell River Mirror . 164 TV This Week (Cranbrook) . 352 Armstrong Campbell River TV Association . 83 Grand Forks CFWB-AM, 1490 kHz . 109 Creston CKGF-AM, 1340 kHz. 112 Armstrong Advertiser . 164 Creston Valley Advance. -

BAYHAM TOWNSHIP 4 - 33 Geology 4 Climate 11 Natural Vegetation 15 Soils 17 Land T,Ypes 27

BAIHAM TOWNSHIP By Herbert Alexander Augustine A Thesis Submitted to the Department of Geogra~ in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts McMaster University February 1958 i??~J 77 '"'-~ I Y.!>ii • ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The writer wishes to express his appreciation for the advice and aid received from Dr. H. A. Wood, who supervised this study and from Dr. H. R. Thompson, both of the Department of Geography at McMaster University. Thanks and gratitude is also due to the writer's wife who typed this thesis. Mention must also be made of the co-operation received from the members of the Dominion Experimental Substation at Delhi, Ontario and also from Mr. D. Valley, the Clerk of B~ham Township. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Pages PREFACE 1 I PHYSICAL GEOORAPHY OF BAYHAM TOWNSHIP 4 - 33 Geology 4 Climate 11 Natural Vegetation 15 Soils 17 Land T,ypes 27 II HISTORY 34 - 48 Indian Period 34 Forest Removal and Early Agricultural Development 35 Extensive Agriculture 43 Intensive Agriculture 47 III PRESENT FEATURES 49 - 97 Agricultural Land Use 49 Urban Land Use 74 IV CONCLUSIONS 98 APPENDIX A 99 -108 APPENDIX B 109 BIBLIOGRAPHY 110 iii LIST OF PHOTOGRAPHS River Dissection 7 Shoreline Erosion 9 Bluff on Lake Erie 9 Reforested Sand Dunes 16 Plainfield Sand Profile 16 Deltaic Sands 21 Sand Dunes 26 Vienna Land TYpe 26 Strat't'ordville Land TYpe .30 Corinth Land Type .32 Gully Erosion 5.3 Field - Cash Crop Region 5.3 Corn Field 58 Pasture - Dairy Region 58 Farm Pond 62 Erosion 62 Tobacco Field 65 Tobacco Land After Harvest 65 -

AAU Ice Hockey Newsletter

AAU Ice Hockey Sports for all, Forever June 1, 2013 Volume 1, Issue 3 T h e C a n a d i a n I n d e p e n d e n t H o c k e y F e d e r a t i o n a n d A A U H o c k e y j o i n f o r c e s ! BARRIE ONTARIO: AAU Hockey is proud to welcome our Canadian members into the AAU family, forming a cross-border alliance of new opportunities. The CIHF website can be found at: www.cihfhockey.com Editor Keith Kloock The Canadian Independent Hockey Federation (CIHF) brings their 21220 Wellington league, associations, teams and thousands of members into the Amateur Woodhaven, MI 48183 Athletic Union (AAU). AAU members may now cooperate to host AAU (734) 692-5158 sanctioned tournaments in both the US and Canada. Published monthly for the benefit and interest of AAU Ice CIHF competition levels range from House (HL) through Hockey participants. Representative (Rep). For our US readers, Rep level could best be AAU Leagues, Administrators, described here in the US as Select and/or (A) level travel. as well as Team Coaches and/ US and Canadian teams should also be aware that the 6U (Mini-mite or Managers are encouraged to submit articles and notices classification born in 2007 or later here in the US) are known as Tyke in to: Canada. Similarly, 8U (Mite born 2005 or later) are known as Novice and [email protected] 10U (Squirt born 2003 or later) are known as Atom in Canada. -

South Central Ontario Region Ontario Central South COUNTY HALDIMAND CITY of HAMILTON Middleport VE R E New Credit

REGIONAL WELLINGTON COUNTY MUNICIPALITY South Central Ontario Region OF HALTON LAKE HURON HURON CITY OF COUNTY STRATFORD REGIONAL PERTH MUNICIPALITY COUNTY Tavistock OF WATERLOO 8 Plattsville 59 13 Centralia 3 Glen Morris East Zorra Bright Whalen Corners 8 CITY OF Mount Carmel TOWN OF HAMILTON Corbett Blandford St. George ST. MARYS Harrington 5 24A 401 Harrisburg 4 6 119 Lucan Biddulph 24 Y 13 Granton Uniondale T 23 UN Blenheim O Osborne Corners 99 Lakeside C Innerkip Clandeboye 59 32 3 5 81 7 Medina D Paris Lucan R Hamilton O Tavistock 23 International F Princeton Airport North Middlesex 24 X 59 2 403 Elginfield Parkhill Falkland O 2 20 Gobles Sylvan 7 Embro Cainsville Ailsa Craig 16 25 7 Eastwood Kintore Creditville Zorra Woodstock Brantford 17 Denfield 403 24 Airport Bryanston T Brantford 53 Birr AN Onondaga 55 28 R 18 119 B Mount Vernon 54 Thorndale 53 Burford Y 2 Cathcart Middleport Nairn Oxford Centre 23 9 NT 18 81 24 U 16 19 4 O Ilderton 59 Thames Beachville Mount Pleasant C 6 401 4 Y N Ohsweken X Ballymote Sweaburg Harley T Centre Burtch AT Keyser 27 N E Thamesford 28 U I S 17 202 O V E 20 C E New Durham 24 R L 119 Arva London Ingersoll E International Foldens 4 S D 119 E Middlesex Centre 21 Airport 2 R 45 VE ID Scotland Oakland 59 Coldstream 73 Burgessville Crumlin 9 Adelaide M Holbrook 3 Hickory Corner Poplar Hill 22 Lobo 32 New Credit 22 Melrose Hyde Park London Salford Kelvin Wilsonville Bealton Boston 402 Dorchester Putnam Norwich 18 Adelaide 29 Norwich 81 39 Nilestown Vanessa 9 19 LAMBTON -

Summer 2008 • Published at Vittoria, Ontario (519) 426-0234

750,000 Birds Banded 13 June Callwood Award 3-4 Alec Godden - a V&DF Hero 6-7 Long Point Biosphere 10 SOME Awesome Kids Awards 11-12 Lorraine Fletcher 8-9 Clara Bingleman 13-14 Magnificent Seven 20 OF THE Damn Dam! 14-15 One More ‘Minor’ decision! 18 Fantastic Year for Vittoria 3 Ontario Volunteer Service Awards 5 Farm Credit Corporation AgriSpirit Fund 5-6 St. Michael’s Champs 12-13 STUFF Gravy on Your Fries? 16-17 Sweet Corn Central 15-16 Innovative Farmers 12 Contributors + Volunteers = ‘Magic’ 2-3 INSIDE Jeanne Harding 9-10 Vic Gibbons 7-8 NO. 23 – SUMMER 2008 • PUBLISHED AT VITTORIA, ONTARIO (519) 426-0234 The Vittoria Booster The Vittoria Booster Newsletter is published twice a year by The Vittoria & District Foundation for its Members and Supporters. website: http://www.vittoria.on.ca e-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] A nn before a person’s name indicates that he or she is a member of The Vittoria & District Foundation. Milestone Anniversaries Celebrated Shirley and Ray Howick, 50 years on March 29 In Memoriam nnGinger and nnLarry Stanley, 45 years on April 6 Marjorie and Sam Kozak, 55 years on May 9 nn nn Robert Daniel “Bob” Benz, æ 58, on December 25 Ruth and Doug Gundry, 50 years on June 7 nn nnPhyllis and nnWilly Pollet, 45 years on June 7 Florence (Curry) Stephens, æ 91 on December 29 nn nn Marion Alice (Duxbury) Matthews, on December 29 Virginia and Tom Drayson, 50 years on June 28 Shelly Lillian Eaker, æ 73 on January 1 Harvey Aspden, æ 79 on January 1 ANNIVERSARIES OVER 60 CLUB Cecil Orval Carpenter, æ 53 on -

The Impact of ABC Canada's LEARN Campaign. Results of a National Research Study

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 405 472 CE 073 669 AUTHOR Long, Ellen TITLE The Impact of ABC Canada's LEARN Campaign. Results of a National Research Study. INSTITUTION ABC Canada, Toronto (Ontario). SPONS AGENCY National Literacy Secretariat, Ottawa (Ontario). PUB DATE Jul 96 NOTE 99p. PUB TYPE Reports Research/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adult Basic Education; *Adult Literacy; Adult Programs; *Advertising; Foreign Countries; High School Equivalency Programs; *Literacy Education; Marketing; *Program Effectiveness; *Publicity IDENTIFIERS *Canada; *Literacy Campaigns ABSTRACT An impact study was conducted of ABC CANADA's LEARN campaign, a national media effort aimed at linking potential literacy learners with literacy groups. Two questionnaires were administered to 94 literacy groups, with 3,557 respondents. Findings included the following:(1) 70 percent of calls to literacy groups were from adult learners aged 16-44;(2) more calls were received from men in rural areas and from women in urban areas; (3) 77 percent of callers were native English speakers;(4) 80 percent of callers had not completed high school, compared with 38 percent of the general population; (5) about equal numbers of learners were seeking elementary-level literacy classes and high-school level classes;(6) 44 percent of all calls to literacy organizations were associated with the LEARN campaign; and (7) 95 percent of potential learners who saw a LEARN advertisement said it helped them decide to call. The study showed conclusively that the LEARN campaign is having a profound impact on potential literacy learners and on literacy groups in every part of Canada. (This report includes 5 tables and 24 figures; 9 appendixes include detailed information on the LEARN campaign, the participating organizations, the surveys, and the impacts on various groups.) (KC) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Deb Landon, Executive Director 519-485-1801 58 Thames St. South

Community Grant Application Township of South-West Oxford 312915 Dereham Line, Mount Elgin, ON N0J 1N0 Phone: 519-485-0477 Fax: 519-485-2932 Email: [email protected] Web: www.swox.org Organization Name: Primary Contact Name: Phone Number: Secondary Phone: Email: Secondary Email: Mailing Address: ________________________________________________________________________________________ PO Box Address ________________________________________________________________________________________ City Prov Postal Code Provide basic information about the organization and what it does. Amount of grant requested: $ _____________ Explain how the grant funds will be used, and why the funds are needed: Was a Township Grant provided to your organization in the previous fiscal year? Yes No If yes, please provide details on how it was used and how it made a difference: Please attach updated copy of your Community Group Financial Statement. *Please note- grant requests, once submitted to the Township, are public information and will be dealt with in open, public Council meeting. Big Brothers Big Sisters of Ingersoll, Tillsonburg Area 2017 Approved Budget REV Apr19, 2017 REVENUE Bowl for Kids Sake 40000 Curl for Kids Sake 20000 Bid for Kids Sake 43000 Other Events 5000 TOTAL SPECIAL EVENTS 108,000 Nevada-Ingersoll (Available) 0 Nevada-Ingersoll (King St Variety) 1000 Nevada-SW Oxford (Available) 1000 Nevada-Thamesford (Mac's) 7500 Nevada-Tillsonburg (Mac's) 12000 TOTAL GAMING 21,500 United Way Member Funding 74000 United Way Designated Pledges 500 Municipal