Greeks and Macedonians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Incised and Impressed Pottery During the Neolithic Period in Western Macedonia

Incised and impressed pottery during the Neolithic period in Western Macedonia Magdalini Tsigka SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) in the Classical Archaeology and the Ancient History of Macedonia December 2018 Thessaloniki – Greece 2 Student Name: Magdalini Tsigka SID: 2204150030 Supervisor: Prof. S. M. Valamoti I hereby declare that the work submitted is mine and that where I have made use of another’s work, I have attributed the source(s) according to the Regulations set in the Student’s Handbook. December 2018 Thessaloniki - Greece 3 Preface This study is the completion of the postgraduate course of MA in the Classical Archaeology and the Ancient History of Macedonia at the International University of Thessaloniki. In order for this thesis to be completed, the contribution of some people was important. First of all, I would like to thank Prof. S. M. Valamoti who accepted to supervise my thesis and encouraged me in all its stages. I would also like to thank Dr. A. Dimoula who helped me throughout all the steps for its completion, from finding the subject up to the end of my work. She was always present to direct me and to solve any questions or concerns about the subject. Then I want to thank L. Gkelou, archaeologist of the Ephorate of Florina, for entrusting me material from the excavation of Anargyroi VIIc and made this study possible despite all the adversities. Also, I would like to thank the Director of the Ephorate of Florina, Dr C. Ziota, for the discussion and the information she gave me during my study of the material. -

2. Customs of the Ancient Macedon Macedonian National Traditio The

Page No.23 2. Customs of the Ancient Macedonians in Macedonian National Tradition Lidija Kovacheva Assistant Professor Classical (ancient) studies University EURO Balkan Skopje Macedonia, the former Yugoslav Republic of ORCID iD: http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1652-1460 URL: http://eurobalkan/academia.edu E-Mail: [email protected] Abstract: The impact of the methodological research of this paper is to highlight ancient Macedonian customs and their influence in the modern Republic of Macedonia. Rather than being altered, vestiges of the past are almost unchanged in some rural areas, as are Macedonian folk beliefs. Indigenous traditions of the ancient Macedonians abounded with numerous ritual activities, although to some extent correspond with the customs of other ancient peoples. However, these practices do have specific features that characterize the folk tradition of the ancient Macedonians interpreted and can be seen as guardians of the Macedonian identity. Although 2,000 years have passed from the ancient period to the present, and it is a bit hypothetical to interpret the rudiments of customs and celebrations from that time, we can allow ourselves to conclude that certain ritual actions from the ancient period, although modified, still largely correspond to the current Macedonian folk customs and beliefs, both in terms of the time of celebration and in terms of ritual actions, procedures and symbolism. Their continuity reflects the Macedonian identity, from antiquity to today. Keywords: Customs, beliefs, ancient Macedonian, Macedonian folk tradition, vestiges Vol. 4 No. 1 (2016) Issue- March ISSN 2347-6869 (E) & ISSN 2347-2146 (P) Customs of the Ancient Macedonians in Macedonian National Tradition by Kovacheva, L. -

Agricultural Practices in Ancient Macedonia from the Neolithic to the Roman Period

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Hellenic University: IHU Open Access Repository Agricultural practices in ancient Macedonia from the Neolithic to the Roman period Evangelos Kamanatzis SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) in Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean Studies January 2018 Thessaloniki – Greece Student Name: Evangelos Kamanatzis SID: 2201150001 Supervisor: Prof. Manolis Manoledakis I hereby declare that the work submitted is mine and that where I have made use of another’s work, I have attributed the source(s) according to the Regulations set in the Student’s Handbook. January 2018 Thessaloniki - Greece Abstract This dissertation was written as part of the MA in Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean Studies at the International Hellenic University. The aim of this dissertation is to collect as much information as possible on agricultural practices in Macedonia from prehistory to Roman times and examine them within their social and cultural context. Chapter 1 will offer a general introduction to the aims and methodology of this thesis. This chapter will also provide information on the geography, climate and natural resources of ancient Macedonia from prehistoric times. We will them continue with a concise social and cultural history of Macedonia from prehistory to the Roman conquest. This is important in order to achieve a good understanding of all these social and cultural processes that are directly or indirectly related with the exploitation of land and agriculture in Macedonia through time. In chapter 2, we are going to look briefly into the origins of agriculture in Macedonia and then explore the most important types of agricultural products (i.e. -

Copyrighted Material

9781405129992_6_ind.qxd 16/06/2009 12:11 Page 203 Index Acanthus, 130 Aetolian League, 162, 163, 166, Acarnanians, 137 178, 179 Achaea/Achaean(s), 31–2, 79, 123, Agamemnon, 51 160, 177 Agasicles (king of Sparta), 95 Achaean League: Agis IV and, agathoergoi, 174 166; as ally of Rome, 178–9; Age grades: see names of individual Cleomenes III and, 175; invasion grades of Laconia by, 177; Nabis and, Agesilaus (ephor), 166 178; as protector of perioecic Agesilaus II (king of Sparta), cities, 179; Sparta’s membership 135–47; at battle of Mantinea in, 15, 111, 179, 181–2 (362 B.C.E.), 146; campaign of, in Achaean War, 182 Asia Minor, 132–3, 136; capture acropolis, 130, 187–8, 192, 193, of Phlius by, 138; citizen training 194; see also Athena Chalcioecus, system and, 135; conspiracies sanctuary of after battle of Leuctra and, 144–5, Acrotatus (king of Sparta), 163, 158; conspiracy of Cinadon 164 and, 135–6; death of, 147; Acrotatus, 161 Epaminondas and, 142–3; Actium, battle of, 184 execution of women by, 168; Aegaleus, Mount, 65 foreign policy of, 132, 139–40, Aegiae (Laconian), 91 146–7; gift of, 101; helots and, Aegimius, 22 84; in Boeotia, 141; in Thessaly, Aegina (island)/Aeginetans: Delian 136; influence of, at Sparta, 142; League and,COPYRIGHTED 117; Lysander and, lameness MATERIAL of, 135; lance of, 189; 127, 129; pro-Persian party on, Life of, by Plutarch, 17; Lysander 59, 60; refugees from, 89 and, 12, 132–3; as mercenary, Aegospotami, battle of, 128, 130 146, 147; Phoebidas affair and, Aeimnestos, 69 102, 139; Spartan politics and, Aeolians, -

4. Barsine, Daughter of Artabazus

Alexander’s Lovers by Andrew Chugg 4. Barsine, Daughter of Artabazus Barsine was by birth a minor princess of the Achaemenid Empire of the Persians, for her father, Artabazus, was the son of a Great King’s daughter.197 It is known that his father was Pharnabazus, who had married Apame, the daughter of Artaxerxes II, some time between 392 - 387BC.198 Artabazus was a senior Persian Satrap and courtier and was latterly renowned for his loyalty first to Darius, then to Alexander. Perhaps this was the outcome of a bad experience of the consequences of disloyalty earlier in his long career. In 358BC Artaxerxes III Ochus had upon his accession ordered the western Satraps to disband their mercenary armies, but this edict had eventually edged Artabazus into an unsuccessful revolt. He spent some years in exile at Philip’s court during Alexander’s childhood, starting in about 352BC and extending until around 349BC,199 at which time he became reconciled with the Great King. It is likely that his daughter Barsine and the rest of his immediate family accompanied him in his exile, so it is feasible that Barsine knew Alexander when they were both still children. Plutarch relates that she had received a “Greek upbringing”, though in point of fact this education could just as well have been delivered in Artabazus’ Satrapy of Hellespontine Phrygia, where the population was predominantly ethnically Greek. As a young girl, Barsine appears to have married Mentor,200 a Greek mercenary general from Rhodes. Artabazus had previously married the sister of this Rhodian, so Barsine may have been Mentor’s niece. -

Philip II of Macedon: a Consideration of Books VII IX of Justin's Epitome of Pompeius Trogus

Durham E-Theses Philip II of Macedon: a consideration of books VII IX of Justin's epitome of Pompeius Trogus Wade, J. S. How to cite: Wade, J. S. (1977) Philip II of Macedon: a consideration of books VII IX of Justin's epitome of Pompeius Trogus, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10215/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. PHILIP II OF MACEDON: A CONSIDERATION OF BOOKS VII - IX OF JUSTIN* S EPITOME OF POMPEIUS TROGUS THESIS SUBMITTED IN APPLICATION FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS - by - J. S. WADE, B. A. DEPARTMENT OF CLASSICS UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM OCTOBER 1977 ABSTRACT The aim of this dissertation is two-fold: firstly to examine the career and character of Philip II of Macedon as portrayed in Books VII - IX of Justin's epitome of the Historiae Phillppicae .of Pompeius Trqgus, and to consider to what extent Justin-Trogus (a composite name for the author of the views in the text of Justin) furnishes accurate historical fact, and to what extent he paints a one-sided interpretation of the events, and secondly to identify as far as possible Justin's principles of selection and compression as evidenced in Books VII - IX. -

Aiani—Historical and Geographical Context

CHAPTER 5 AIANI—HISTORICAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL CONTEXT G. Karamitrou-Mentessidi Aiani—Elimiotis—Upper Macedonia According to the foundation myth preserved by Stephanos of Byzantium, “Aiani, a Macedonian city, was built by Aianos, a son of Elymos the Tyr- rhenian king, who migrated to Macedonia, ‘Aianaios’ was the ethnikon.” A reference to the city of Aiani was found by the French academic L. Heuzey in 1861 in two inscriptions in churches in the village of Kalliani (whose name may derive from “kali Aiani,” meaning “fair Aiani,”: in 1926 it was renamed Aiani). They led to various theories about the site of the settle- ment and its urban organization. The problem was not solved until offfijicial excavations began. Even if an urban settlement by the name of Elimeia did also exist, Aiani became the capital of Elimiotis at a very early date. The district of Elimeia or Elimiotis, bordering Orestis and Eordaea to the north, occupied the southern part of Upper Macedonia on both sides of the middle reach of the River Haliacmon, although its exact territorial extent is difffijicult to determine. During the Hellenistic era it appears to have included the region of Tymphaea to the west and, perhaps at an earlier date, the northern part of the Perrhaebian Tripolitis (Pythium, Azorus, and Doliche). Territorial disputes between Elimeia and its neigh- bours occurred, as can be seen in a Latin inscription found at Doliche, in which the emperor Trajan (101 ad) defijined the boundary between the Elimiotae and the inhabitants of Doliche by reviving an earlier ruling by King Amyntas III (393–369 bc) on the same issue. -

Contesting the Greatness of Alexander the Great: the Representation of Alexander in the Histories of Polybius and Livy

ABSTRACT Title of Document: CONTESTING THE GREATNESS OF ALEXANDER THE GREAT: THE REPRESENTATION OF ALEXANDER IN THE HISTORIES OF POLYBIUS AND LIVY Nikolaus Leo Overtoom, Master of Arts, 2011 Directed By: Professor Arthur M. Eckstein, Department of History By investigating the works of Polybius and Livy, we can discuss an important aspect of the impact of Alexander upon the reputation and image of Rome. Because of the subject of their histories and the political atmosphere in which they were writing - these authors, despite their generally positive opinions of Alexander, ultimately created scenarios where they portrayed the Romans as superior to the Macedonian king. This study has five primary goals: to produce a commentary on the various Alexander passages found in Polybius’ and Livy’s histories; to establish the generally positive opinion of Alexander held by these two writers; to illustrate that a noticeable theme of their works is the ongoing comparison between Alexander and Rome; to demonstrate Polybius’ and Livy’s belief in Roman superiority, even over Alexander; and finally to create an understanding of how this motif influences their greater narratives and alters our appreciation of their works. CONTESTING THE GREATNESS OF ALEXANDER THE GREAT: THE REPRESENTATION OF ALEXANDER IN THE HISTORIES OF POLYBIUS AND LIVY By Nikolaus Leo Overtoom Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2011 Advisory Committee: Professor Arthur M. Eckstein, Chair Professor Judith P. Hallett Professor Kenneth G. Holum © Copyright by Nikolaus Leo Overtoom 2011 Dedication in amorem matris Janet L. -

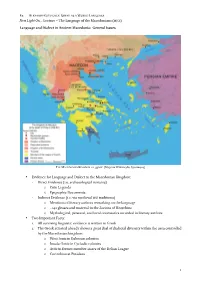

1 Language and Dialect in Ancient Macedonia

E2 — ALEXANDER’S LEGACY: GREEK AS A WORLD LANGUAGE New Light On… Lecture – The Language of the Macedonians (MJCS) Language and Dialect in Ancient Macedonia: General Issues THE MACEDONIAN KINGDOM CA. 336 BC (Map via Wikimedia Commons) • Evidence for Language and Dialect in the Macedonian Kingdom: - Direct Evidence (i.e. archaeological remains) o Coin Legends o Epigraphic Documents - Indirect Evidence (i.e. via medieval MSS traditions) o Mentions of literary authors remarking on the language o ~140 glosses and material in the Lexicon of Hesychius o Mythological, personal, and local onomastics recorded in literary authors • Two Important Facts: 1. All surviving linguistic evidence is written in Greek 2. The Greek attested already shows a great deal of dialectal diversity within the area controlled by the Macedonian kingdom: o West Ionic in Euboean colonies o Insular Ionic in Cycladic colonies o Attic in former member states of the Delian League o Corinthian at Potidaea 1 E2 — ALEXANDER’S LEGACY: GREEK AS A WORLD LANGUAGE New Light On… Lecture – The Language of the Macedonians (MJCS) o Attic-Ionic koiné in Macedonian official inscriptions Regarding the ‘Greekness’ of the Macedonians and their Language(s) • Evidence from literary sources is divided on the original ethnic and linguistic identity of the Ancient Macedonians: o Hesiod fr. 7: Eponymous ancestor Μακεδών born to Zeus and one of Deucalion’s daughters. o Herodotus (5.22, 8.137-139) strongly states a belief that Macedonians were Greeks o Thucydides (2.80.5-7, 2.81.6, 4.124.1) possibly considers Macedonians to be βάρβαροι. o Aristotle (1324b) includes Macedonians in a list of ἔθνη with despotic practices (ἐν τοῖς ἔθνεσι πᾶσι τοῖς δυναµένοις πλεονεκτεῖν), but makes no reference to language. -

Frances Pownall, Reviewing Joseph Roisman and Ian Worthington Eds

Joseph Roisman and Ian Worthington, eds., A Companion to Ancient Macedonia (Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World). Malden, MA and Oxford: Wiley- Blackwell, 2010. Pp. xxviii + 668. ISBN 978-1-4051-7936-2. $207.95. Readers expecting another volume on Macedonia’s most famous citizen, Alexander the Great, subject of a proliferating number of collected essays in recent years,1 will perhaps be disappointed, for the great man himself is the nominal subject of only one chapter out of the 27 contained in this new collection (although naturally references to him abound throughout). The focus on in this volume on Macedonia as a whole is explained in an introductory chapter (E.M. Anson) as a deliberate choice in response to the trend in scholarship over the last half century away from an “obsession with Alexander” towards a more holistic view of the land which produced both the conqueror himself and the Hellenistic era after his death, during which Macedonia continued to play an important role on the world stage. As promised, this volume does much to situate Alexander both in terms of his Macedonian background and the continuing impact that he had on his native land, and contains a much wider chronological range than earlier volumes on Macedonian history, which tend to cover events only to the Roman conquest and ensuing loss of political liberty.2 The volume opens with a review of the ancient evidence for Macedonia and the Macedonians. P.J. Rhodes surveys the literary and epigraphic evidence up to the Roman conquest, and rightly stresses that most of this material is written not by Macedonians, but by Greeks, and therefore gives their perspective on the contemporary Macedonians, which was generally either uninformed or outright hostile. -

What May Philip Have Learnt As a Hostage in Thebes? Hammond, N G L Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Winter 1997; 38, 4; Proquest Pg

What may Philip have learnt as a hostage in Thebes? Hammond, N G L Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Winter 1997; 38, 4; ProQuest pg. 355 What May Philip Have Learnt as a Hostage in Thebes? N. c. L. Hammond HE BELIEF that Philip did learn some lessons in Thebes was clearly stated in three passages.1 After denouncing the slug Tgishness of the Athenians, Justin (6.9.7) wrote that Philip "having been held hostage in Thebes for three years and having been instructed in the fine qualities of Epaminondas and Pelo pidas" was enabled by the inactivity of the Greeks to impose on them the yoke of servitude. The source of this passage was clearly Theopompus. 2 Justin wrote further as follows: "This thing [peace with Thebes] gave very great promotion to the outstanding natural ability of Philip" (7.5.2: quae res Philippo maxima incrementa egregiae indolis dedit), "seeing that Philip laid the first foundations of boyhood as a hostage for three 1 The following abbreviations are used: Anderson=J. K. Anderson, Military Theory and Practice in the Age of Xenophon (Berkeley 1970); Aymard=A. Aymard, "Philippe de Macedoine, otage a Thebes, REA 56 (1954) 15-26; Buckler=J. Buckler, "Plutarch on Leuktra," SymbOslo 55 (1980) 75-93; Ellis=J. R. Ellis, Philip II and Macedonian Imperialism (London 1976); Ferrill=A. Ferrill, The Origins of War from the Stone Age to Alexander the Great (London 1985); Geyer=F. Geyer, Makedonien bis zur Thronbesteigung Philippe II (Munich 1939); Hammond, Coll. St.-N. G. L. Hammond, Col lected Studies I-IV (Amsterdam 1993-97); Hammond, Philip=id., Philip of Macedon (London 1994); Hammond, "Training"=id., "Training in the Use of the Sarissa and its Effect in Battle, n Antichthon 14 (1980) 53-63; Hat zopoulos,=M. -

Position of the Ancient Macedonian Language and the Name of the Contemporary Makedonski

SBORNlK PRACl FH.OZOFICK& FAKULTY BRNliNSKE UNIVERZ1TY STUDIA MINORA FACULTATIS PHILOSOPraCAE UNIVERSITATIS BRUNENSIS Ei6, 1991 PETAR HR ILIEVSKI POSITION OF THE ANCIENT MACEDONIAN LANGUAGE AND THE NAME OF THE CONTEMPORARY MAKEDONSKI 1. The language spoken for centuries by people of the largest part of a small central Balkan country - Macedonia - is know under the name Makedonski (Macedonian). Rich folklore has been created in Makedonski, and during the last fifty years widely acknowledged literary writings have appeared in it. Under this name it has been taught abroad in a certain number of university centres, and it is included among the other European languages as a specific Balkan Slavic language. However, the southern neighbours cannot reconcile themselves to this name, because they think that it is Greek, taken by the "Republic of Skopje as a pretext for some territorial claim". In their thesis, thunderously propagated throughout the world, they identity themselves with ancient Macedonians, emphasising that ancient Macedonian was a Greek dialect like Ionian and Aeolian. The aim of this paper is to throw some light on the problem imposed on the political, scientific, scholarly and cultural circles of the world, in order to answer the question whether somebody's rights are usurped by the use of the name Macedonia/n. An analysis of the scarce survivals from the ancient Macedonian in comparison with some Greek parallels will show whether ancient Macedonian a Greek dialect, or a separate language, different from Greek. But, as the modern Greeks now pretend to an ethnical identity with the ancient Macedonians. I cannot avoid some historical data about the relations between classical Greeks and their contemporaneous Macedonians.