Frances Pownall, Reviewing Joseph Roisman and Ian Worthington Eds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2. Customs of the Ancient Macedon Macedonian National Traditio The

Page No.23 2. Customs of the Ancient Macedonians in Macedonian National Tradition Lidija Kovacheva Assistant Professor Classical (ancient) studies University EURO Balkan Skopje Macedonia, the former Yugoslav Republic of ORCID iD: http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1652-1460 URL: http://eurobalkan/academia.edu E-Mail: [email protected] Abstract: The impact of the methodological research of this paper is to highlight ancient Macedonian customs and their influence in the modern Republic of Macedonia. Rather than being altered, vestiges of the past are almost unchanged in some rural areas, as are Macedonian folk beliefs. Indigenous traditions of the ancient Macedonians abounded with numerous ritual activities, although to some extent correspond with the customs of other ancient peoples. However, these practices do have specific features that characterize the folk tradition of the ancient Macedonians interpreted and can be seen as guardians of the Macedonian identity. Although 2,000 years have passed from the ancient period to the present, and it is a bit hypothetical to interpret the rudiments of customs and celebrations from that time, we can allow ourselves to conclude that certain ritual actions from the ancient period, although modified, still largely correspond to the current Macedonian folk customs and beliefs, both in terms of the time of celebration and in terms of ritual actions, procedures and symbolism. Their continuity reflects the Macedonian identity, from antiquity to today. Keywords: Customs, beliefs, ancient Macedonian, Macedonian folk tradition, vestiges Vol. 4 No. 1 (2016) Issue- March ISSN 2347-6869 (E) & ISSN 2347-2146 (P) Customs of the Ancient Macedonians in Macedonian National Tradition by Kovacheva, L. -

Agricultural Practices in Ancient Macedonia from the Neolithic to the Roman Period

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Hellenic University: IHU Open Access Repository Agricultural practices in ancient Macedonia from the Neolithic to the Roman period Evangelos Kamanatzis SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) in Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean Studies January 2018 Thessaloniki – Greece Student Name: Evangelos Kamanatzis SID: 2201150001 Supervisor: Prof. Manolis Manoledakis I hereby declare that the work submitted is mine and that where I have made use of another’s work, I have attributed the source(s) according to the Regulations set in the Student’s Handbook. January 2018 Thessaloniki - Greece Abstract This dissertation was written as part of the MA in Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean Studies at the International Hellenic University. The aim of this dissertation is to collect as much information as possible on agricultural practices in Macedonia from prehistory to Roman times and examine them within their social and cultural context. Chapter 1 will offer a general introduction to the aims and methodology of this thesis. This chapter will also provide information on the geography, climate and natural resources of ancient Macedonia from prehistoric times. We will them continue with a concise social and cultural history of Macedonia from prehistory to the Roman conquest. This is important in order to achieve a good understanding of all these social and cultural processes that are directly or indirectly related with the exploitation of land and agriculture in Macedonia through time. In chapter 2, we are going to look briefly into the origins of agriculture in Macedonia and then explore the most important types of agricultural products (i.e. -

1 Language and Dialect in Ancient Macedonia

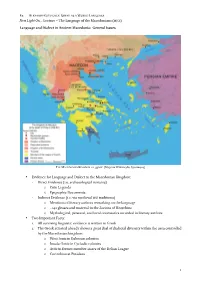

E2 — ALEXANDER’S LEGACY: GREEK AS A WORLD LANGUAGE New Light On… Lecture – The Language of the Macedonians (MJCS) Language and Dialect in Ancient Macedonia: General Issues THE MACEDONIAN KINGDOM CA. 336 BC (Map via Wikimedia Commons) • Evidence for Language and Dialect in the Macedonian Kingdom: - Direct Evidence (i.e. archaeological remains) o Coin Legends o Epigraphic Documents - Indirect Evidence (i.e. via medieval MSS traditions) o Mentions of literary authors remarking on the language o ~140 glosses and material in the Lexicon of Hesychius o Mythological, personal, and local onomastics recorded in literary authors • Two Important Facts: 1. All surviving linguistic evidence is written in Greek 2. The Greek attested already shows a great deal of dialectal diversity within the area controlled by the Macedonian kingdom: o West Ionic in Euboean colonies o Insular Ionic in Cycladic colonies o Attic in former member states of the Delian League o Corinthian at Potidaea 1 E2 — ALEXANDER’S LEGACY: GREEK AS A WORLD LANGUAGE New Light On… Lecture – The Language of the Macedonians (MJCS) o Attic-Ionic koiné in Macedonian official inscriptions Regarding the ‘Greekness’ of the Macedonians and their Language(s) • Evidence from literary sources is divided on the original ethnic and linguistic identity of the Ancient Macedonians: o Hesiod fr. 7: Eponymous ancestor Μακεδών born to Zeus and one of Deucalion’s daughters. o Herodotus (5.22, 8.137-139) strongly states a belief that Macedonians were Greeks o Thucydides (2.80.5-7, 2.81.6, 4.124.1) possibly considers Macedonians to be βάρβαροι. o Aristotle (1324b) includes Macedonians in a list of ἔθνη with despotic practices (ἐν τοῖς ἔθνεσι πᾶσι τοῖς δυναµένοις πλεονεκτεῖν), but makes no reference to language. -

Position of the Ancient Macedonian Language and the Name of the Contemporary Makedonski

SBORNlK PRACl FH.OZOFICK& FAKULTY BRNliNSKE UNIVERZ1TY STUDIA MINORA FACULTATIS PHILOSOPraCAE UNIVERSITATIS BRUNENSIS Ei6, 1991 PETAR HR ILIEVSKI POSITION OF THE ANCIENT MACEDONIAN LANGUAGE AND THE NAME OF THE CONTEMPORARY MAKEDONSKI 1. The language spoken for centuries by people of the largest part of a small central Balkan country - Macedonia - is know under the name Makedonski (Macedonian). Rich folklore has been created in Makedonski, and during the last fifty years widely acknowledged literary writings have appeared in it. Under this name it has been taught abroad in a certain number of university centres, and it is included among the other European languages as a specific Balkan Slavic language. However, the southern neighbours cannot reconcile themselves to this name, because they think that it is Greek, taken by the "Republic of Skopje as a pretext for some territorial claim". In their thesis, thunderously propagated throughout the world, they identity themselves with ancient Macedonians, emphasising that ancient Macedonian was a Greek dialect like Ionian and Aeolian. The aim of this paper is to throw some light on the problem imposed on the political, scientific, scholarly and cultural circles of the world, in order to answer the question whether somebody's rights are usurped by the use of the name Macedonia/n. An analysis of the scarce survivals from the ancient Macedonian in comparison with some Greek parallels will show whether ancient Macedonian a Greek dialect, or a separate language, different from Greek. But, as the modern Greeks now pretend to an ethnical identity with the ancient Macedonians. I cannot avoid some historical data about the relations between classical Greeks and their contemporaneous Macedonians. -

STUDIES in the DEVELOPMENT of ROYAL AUTHORITY in ARGEAD MACEDONIA WILLIAM STEVEN GREENWALT Annandale, Virginia B.A., University

STUDIES IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF ROYAL AUTHORITY IN ARGEAD MACEDONIA WILLIAM STEVEN GREENWALT Annandale, Virginia B.A., University of Virginia, 1975 M.A., University of Virginia, 1978 A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Corcoran Department of History University of Virginia May, ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the elements which defined Argead kingship from the mid-seventh until the late fourth centuries B.C. It begins by reviewing the Argead king list where it is argued that the official reckoning of the dynasty's past was exploited in order to secure the throne against rivals, including those who were Argeads. Chapter Two analyzes the principles of Argead succession and concludes that the current theories on the subject are unsatisfactory in face of the e v id enc e. Ra the r, the sources suggest that Argead succession was a function of status where many ingredients were considered before a candidate 1 eg it ima te 1 y ass urned the throne. Among the factors influencing the selection were, the status of a potential heir's mother, age, competence, order of birth, and in lieu of father to son succession, relation to the late monarch. Chapter Three outlines the development of the king's military, judicial, economic, and social responsibilities from the personal monarchy of the early period to the increa~ingly centralized realm of the fourth century. Chapter Four concentrates on the religious aspects of Argead kingship, reviewing the monarch's religious duties· and interpreting a widespread foundation myth as an attempt to distinguish Argead status by its divine origin and its specific cult responsibilities. -

Fallacies and Facts on the Macedonian Issue ©2003 by Marcus a Templar

Fallacies & Facts on Macedonian Issue by Marcus A. Templar, 2003 FALLACIES AND FACTS ON THE MACEDONIAN ISSUE ©2003 BY MARCUS A TEMPLAR There have been certain fallacies circulating for the past few years due to ignorance on the “Macedonian Issue”. It is exacerbated by systematic propaganda emanating from AVNOJ, or communist Yugoslavia and present-day FYROM, and their intransigent ultra-nationalist Diaspora. Fallacy #1 The inhabitants of The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (The FYROM) are ethnic Macedonians, direct descendants of, or related to the ancient Macedonians. Fact #1 The inhabitants of The FYROM are mostly Slavs, Bulgarians and Albanians. They have nothing in common with the ancient Macedonians. Here are some testimonies from The FYROM’s officials: a. The former President of The FYROM, Kiro Gligorov said: “We are Slavs who came to this area in the sixth century ... we are not descendants of the ancient Macedonians" (Foreign Information Service Daily Report, Eastern Europe, February 26, 1992, p. 35). b. Also, Mr Gligorov declared: "We are Macedonians but we are Slav Macedonians. That's who we are! We have no connection to Alexander the Greek and his Macedonia… Our ancestors came here in the 5th and 6th century" (Toronto Star, March 15, 1992). c. On 22 January 1999, Ambassador of the FYROM to USA, Ljubica Achevska gave a speech on the present situation in the Balkans. In answering questions at the end of her speech Mrs. Acevshka said: "We do not claim to be descendants of Alexander the Great … Greece is Macedonia’s second largest trading partner, and its number one investor. -

Ancient Macedonians

Ancient Macedonians This article is about the native inhabitants of the historical kingdom of Macedonia. For the modern ethnic Greek people from Macedonia, Greece, see Macedonians (Greeks). For other uses, see Ancient Macedonian (disambiguation) and Macedonian (disambiguation). From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia ANCIENT MACEDONIANS ΜΑΚΕΔΌΝΕΣ Stag Hunt Mosaic, 4th century BC Languages. Ancient Macedonian, then Attic Greek, and later Koine Greek Religion. ancient Greek religion The Macedonians (Greek: Μακεδόνες, Makedónes) were an ancient tribe that lived on the alluvial plain around the rivers Haliacmonand lower Axios in the northeastern part of mainland Greece. Essentially an ancient Greek people,[1] they gradually expanded from their homeland along the Haliacmon valley on the northern edge of the Greek world, absorbing or driving out neighbouring non-Greek tribes, primarily Thracian and Illyrian.[2][3] They spoke Ancient Macedonian, a language closely related to Ancient Greek, perhaps a dialect, although the prestige language of the region was at first Attic and then Koine Greek.[4] Their religious beliefs mirrored those of other Greeks, following the main deities of the Greek pantheon, although the Macedonians continued Archaic burial practices that had ceased in other parts of Greece after the 6th century BC. Aside from the monarchy, the core of Macedonian society was its nobility. Similar to the aristocracy of neighboring Thessaly, their wealth was largely built on herding horses and cattle. Although composed of various clans, the kingdom of Macedonia, established around the 8th century BC, is mostly associated with the Argead dynasty and the tribe named after it. The dynasty was allegedly founded by Perdiccas I, descendant of the legendary Temenus of Argos, while the region of Macedon perhaps derived its name from Makedon, a figure of Greek mythology. -

Peliganes: the State of the Question and Some Other Thoughts

У Ж 342.5(381) Peliganes: the state of the question and some other thoughts Vojislav Sarakinski Ss. Cyril and Methodius University, Faculty of Philosophy Skopje, Macedonia 1. Contrary to the wealth of evidence for some problems concerning the history of the ancient Macedonian state, the office of peliganes is barely mentioned in the ancient sources, and modern scholars rarely touch upon the problem. It is usually assumed that the name of the office is associated with the Greek word for “grey-haired”, “old”, so the peliganes are therefore translated as a “council of elders”, although, as we shall see, this interpreta tion is hardly based on solid ground. From all that has been written by the scholars — both foreign and domestic1 — one could conclude that the term peliganes signifies local officials, members of the city council, especially in the Macedonian cities in Asia. Yet, there are scholars who doubt that these offi cials had any real powers and, on the basis of the possible etymology of the 1 1 In all honesty, one would struggle to find anything more than a few scarce lines. The only scholarly works in Macedonian historiography that mention this problem are ПРОЕВА, 1997: 74, 166; in somewhat more detail EADEM, 2004: 337; as well as a recendy published note by ПОПОВСКА, 2005. As for scholarly works on the subject abroad, one should note HAMMOND Sc GRIFFITH, 1979: 384, 399, 648. In addition, there are several works that make brief and passing mentions of the peliganes as a “council of elders” wi thout further treatment of the issue, among them WALBANK, 1992: 135- 136; ROUSSEL, 1942-3; RHODES & LEWIS, 1997: 460; VAN DER SPEIC, 2009: 109; MUSTI, 1984; COHEN, 2006: 112, 114; GRAINGER, 1990: 66, 152-153; HATZOPOULOS, 1996: 323, 326, 465, 482; B e r n a r d , 1998: 1208-1210 (non vidi). -

Bulletin of Ancient Macedonian Studies

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. Departament de Ciències de l’Antiguitat i l’Edat Mitjana Karanos BULLETIN OF ANCIENT MACEDONIAN STUDIES http://revistes.uab.cat/karanos 01 ), online ( 3521 - Ancient Macedonian Studies 2604 in Honor of A. B. Bosworth ISSN e 2018 (paper), 6199 - 2604 1, 2018, ISSN Vol. Karanos Bulletin of Ancient Macedonian Studies Vol. 1 (2018) Ancient Macedonian Studies in Honor of A. B. Bosworth President of Honor Secretary F. J. Gómez Espelosín, Marc Mendoza Sanahuja (Universitat Autònoma (Universidad de Alcalá) de Barcelona) Director Edition Borja Antela-Bernárdez, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona) Departament de Ciències de l’Antiguitat i l’Edat Mitjana Editorial Board 08193 Bellaterra (Barcelona). Spain Borja Antela-Bernárdez Tel.: 93 581 47 87. Antonio Ignacio Molina Marín (Universidad de Fax: 93 581 31 14 Alcalá) [email protected] Mario Agudo Villanueva (Universidad Complutense http://revistes.uab.cat/karanos de Madrid) Layout: Borja Antela-Bernárdez Advisory Board F. Landucci (Università Cattolica del Printing Sacro Cuore) Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona E. Carney (Clemson University) Servei de Publicacions D. Mirón (Universidad de Granada) 08193 Bellaterra (Barcelona). Spain C. Rosillo (Universidad Pablo de Olavide) [email protected] W. L. Adams (University of Utah) http://publicacions.uab.cat/ N. Akamatis (International Hellenic University) V. Alonso-Troncoso (Universidad de A Coruña) ISSN: 2604-6199 (paper) A. Domínguez Monedero (Universidad eISSN 2604-3521 (online) Autónoma de Madrid) Dipòsit legal: B 26.673-2018 F. J. Gómez Espelosín (Universidad de Alcalá) W. S. Greenwalt (Santa Clara University) Printed in Spain M. Hatzopoulos (National Hellenic Printed in Ecologic paper Research Foundation) S. -

Remijsen 'Only Greeks at the Olympics

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Only Greeks at the Olympics? Reconsidering the rule against non-Greeks at ‘panhellenic’ games' Remijsen, S. DOI 10.7146/classicaetmediaevalia.v67i0.111033 Publication date 2019 Document Version Final published version Published in Classica et Mediaevalia Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Remijsen, S. (2019). Only Greeks at the Olympics? Reconsidering the rule against non- Greeks at ‘panhellenic’ games'. Classica et Mediaevalia, 67, 1-61. https://doi.org/10.7146/classicaetmediaevalia.v67i0.111033 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:29 Sep 2021 ONLY GREEKS AT THE OLYMPICS? RECONSIDERING THE RULE AGAINST NON-GREEKS AT ‘PANHELLENIC’ GAMES By Sofie Remijsen Summary: This paper argues that the so-called “Panhellenic” games never knew a rule excluding non-Greeks from participation. -

ALEXANDER the GREAT and the MACEDONIAN CONFLICT Loring

CHAPTER THIRTEEN ALEXANDER THE GREAT AND THE MACEDONIAN CONFLICT Loring M. Danforth Alexander the Great is without a doubt the most famous Macedonian who ever lived. No discussion of Macedonia, ancient or modern, is possible without at least some reference to this brilliant general, powerful king, and conqueror of the known world. A 1996 National Geographic article on the newly independent Republic of Macedonia describes Macedonia as "the homeland of Alexander the Great," adding that "today's Macedonians ... trace their name to the empire of Alexander the Great in the fourth century BC" (Vesilind 1996: 124). Comments like these raise the very issue that lies at the heart of the Macedonian conflict, the "global cultural war" (Featherstone 1990: 10) that since the late 1980s has been waged by Greeks and Macedonians in the Balkans and in the diaspora over which group has the right to identify themselves as Macedonians. The Macedonian conflict is a dispute over the name "Macedonia," the glorious legacy of Alexander the Great and the ancient Macedonians, and ultimately the territory of Macedonia itself. For in the crowded Balkan land scape geography and history are bitterly contested, as Greece and Macedonia both assert their mutually exclusive claims over the same places, the same symbols, and the same famous ancestors. 1 I begin this essay with a brief account of the history of the Mace danian conflict and a summary of both the Greek and the Macedonian positions on the issues involved. Drawing on recent theoretical work on nationalism and the construction of national identities and cul tures, I then examine the role of classical archaeology in creating the "symbolic capital" (Bourdieu 1977) with which Greeks and Mace donians each seek to legitimate their own national narratives of his torical continuity with ancient Macedonia. -

Matica Makedonska Skopje, 2009 NAME DISPUTE

PREFACE NAME DISPUTE BETWEEN GREECE AND MACEDONIA STUDENT PROJECT) ( Editors: Svetomir Shkaric Dimitar Apasiev Vladimir Patchev Matica Makedonska Skopje, 2009 1 NAME DISPUTE BETWEEN GREECE AND MACEDONIA (STUDENT PROJECT) Published by Matica Ìàêåäînska [email protected] About the Publisher Rade Siljan Project Leaders Prof. Svetomir Shkaric Ph.D. Prof. Tatjana Petrushevska Ph.D. Editors Svetomir Shkaric Dimitar Apasiev Vladimir Patchev Printed by Makedonija The student project “Name dispute between Greece and Macedonia” was approved by the Teachers’ Council of the Faculty of Law “Iustinianus Primus” from Skopje, with the Resolution No. 02-300/6 from May 05, 2008. 2 PREFACE I had the chance to see works of Macedonian art, beautiful icons and ceramics from Ohrid and other places. I am especially touched by the survival of Macedonia, which has been surrounded by stronger neighbors for centuries… Martin Bernal April 2009 3 NAME DISPUTE BETWEEN GREECE AND MACEDONIA (STUDENT PROJECT) 4 PREFACE CONTENTS P R E F A C E ...................................................................................................... 9 INTRODUCTION ATTRACTIVENESS OF MACEDONIA TO STUDENT SPIRIT...................................................................................... 17 M A C E D O N I A ................................................................................... 19 PART ONE DISPUTE OVER THE NAME MACEDONIA WITH GREECE ........................................................................................ 23 1 HISTORICAL DIMENSION OF THE